INSTITUTE for SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT SEEDS Land Use – Transportation Scenario Matrix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Induced Demand: an Urban and Metropolitan Perspective

Induced Demand: An Urban and Metropolitan Perspective Robert Cervero, Professor Department of City and Regional Planning University of California Berkeley, California E-Mail: [email protected] Paper prepared for Policy Forum: Working Together to Address Induced Demand U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation Eno Transportation Foundation, Incorporated March 2001 Second Revision Induced Demand: An Urban and Metropolitan Perspective Most studies of induced travel demand have been carried out at a fine to medium grain of analysis – either the project, corridor, county, or metropolitan levels. The focus has been on urban settings since cities and suburbs are where the politics of road investments most dramatically get played out. The problems assigned to induced demand – like the inability to stave off traffic congestion and curb air pollution – are quintessentially urban in nature. This paper reviews, assesses, and critiques the state-of-the-field in studying induced travel demand at metropolitan and sub-metropolitan grains of analysis. Its focus is on empirical and ex post examinations of the induced demand phenomenon as opposed to forecasts or simulations. A meta-analysis is conducted with an eye toward presenting an overall average elasticity estimate of induced demand effects based on the best, most reliable research to date. 1. URBAN HIGHWAYS AND TRAVEL: THE POLICY DEBATE Few contemporary issues in the urban transportation field have elicited such strong reactions and polarized political factions as claims of induced travel demand. Highway critics charge that road improvements provide only ephemeral relief – within a few year’s time, most facilities are back to square one, just as congested as they were prior to the investment. -

The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from US Cities

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Real Estate Papers Wharton Faculty Research 10-2011 The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities Gilles Duranton University of Pennsylvania Matthew A. Turner Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Duranton, G., & Turner, M. A. (2011). The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities. American Economic Review, 101 (6), 2616-2652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.6.2616 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence From US Cities Abstract We investigate the effect of lane kilometers of roads on vehicle-kilometers traveled (VKT) in US cities. VKT increases proportionately to roadway lane kilometers for interstate highways and probably slightly less rapidly for other types of roads. The sources for this extra VKT are increases in driving by current residents, increases in commercial traffic, and migration. Increasing lane kilometers for one type of road diverts little traffic omfr other types of road. We find no evidence that the provision of public transportation affects VKT. We conclude that increased provision of roads or public transit is unlikely to relieve congestion. Disciplines Economics | Real Estate This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/real-estate_papers/3 American Economic Review 101 (October 2011): 2616–2652 http://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi 10.1257/aer.101.6.2616 = The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from US Cities† By Gilles Duranton and Matthew A. -

On the Brink: 2021 Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry in the United States

On the Brink: 2021 Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry in the United States BY JOSEPH SCHWIETERMAN, BRIAN ANTOLIN & CRYSTAL BELL JANUARY 30, 2021 CHADDICK INSTITUTE FOR METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AT DEPAUL UNIVERSITY | POLICY SERIES THE STUDY TEAM AUTHORS BRIAN ANTOLIN, JOSEPH P. SCHWIETERMAN AND CRYSTAL BELL CARTOGRAPHY ALL TOGETHER STUDIO AND GRAPHICS ASSISTING MICHAEL R. WEINMAN AND PATRICIA CHEMKA SPERANZA OF PTSI TRANSPORTATION CONTRIBUTORS DATA KIMBERLY FAIR AND MITCH HIRST TEAM COVER BOTTOM CENTER: ANNA SHVETS; BOTTOM LEFT: SEE CAPTION ON PAGE 1; PHOTOGRAPHY TOP AND BOTTOM RIGHT: CHADDICK INSTITUTE The Chaddick Insttute does not receive funding from intercity bus lines or suppliers of bus operators. This report was paid for using general operatng funds. For further informaton, author bios, disclaimers, and cover image captons, see page 20. JOIN THE STUDY TEAM FOR A WEBINAR ON THIS STUDY: Friday, February 19, 2021 from noon to 1 pm CT (10 am PT) | Free Email [email protected] to register or for more info CHADDICK INSTITUTE FOR METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AT DEPAUL UNIVERSITY CONTACT: JOSEPH SCHWIETERMAN, PH.D. | PHONE: 312.362.5732 | EMAIL: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The prognosis for the intercity bus industry remains uncertain due to the weakened financial condition of most scheduled operators and the unanswerable questions about the pace of a post-pandemic recovery. This year’s Outlook for the Intercity Bus Industry report draws attention to some of the industry’s changing fundamentals while also looking at notable developments anticipated this year and beyond. Our analysis evaluates the industry in six areas: i) The status of bus travel booking through January 2021; ii) Notable marketing and service developments of 2020; iii) The decline of the national bus network sold on greyhound.com that is relied upon by travelers on thousands of routes across the U.S. -

S92 Orient Point, Greenport to East Hampton Railroad Via Riverhead

Suffolk County Transit Bus Information Suffolk County Transit Fares & Information Vaild March 22, 2021 - October 29, 2021 Questions, Suggestions, Complaints? Full fare $2.25 Call Suffolk County Transit Information Service Youth/Student fare $1.25 7 DAY SERVICE Youths 5 to 13 years old. 631.852.5200 Students 14 to 22 years old (High School/College ID required). Monday to Friday 8:00am to 4:30pm Children under 5 years old FREE SCHEDULE Limit 3 children accompanied by adult. Senior, Person with Disabilities, Medicare Care Holders SCAT Paratransit Service and Suffolk County Veterans 75 cents Personal Care Attendant FREE Paratransit Bus Service is available to ADA eligible When traveling to assist passenger with disabilities. S92 passengers. To register or for more information, call Transfer 25 cents Office for People with Disabilities at 631.853.8333. Available on request when paying fare. Good for two (2) connecting buses. Orient Point, Greenport Large Print/Spanish Bus Schedules Valid for two (2) hours from time received. Not valid for return trip. to East Hampton Railroad To obtain a large print copy of this or other Suffolk Special restrictions may apply (see transfer). County Transit bus schedules, call 631.852.5200 Passengers Please or visit www.sct-bus.org. via Riverhead •Have exact fare ready; Driver cannot handle money. Para obtener una copia en español de este u otros •Passengers must deposit their own fare. horarios de autobuses de Suffolk County Transit, •Arrive earlier than scheduled departure time. Serving llame al 631.852.5200 o visite www.sct-bus.org. •Tell driver your destination. -

10/21/2020 Public Hearing on The

1 2 3 4 5 SUFFOLK COUNTY LEGISLATURE 6 7 8 PUBLIC HEARING 9 10 11 October 21, 2020 12 13 14 15 A Public Hearing on the 2021 Operating Budget and the Southwest 16 Sewer District Assessment Roll was held via Hybrid/Zoom 17 Videoconferencing in the Rose Y. Caracappa Legislative Auditorium 18 of the William H. Rogers Legislature Building, 725 Veterans 19 Memorial Highway, Smithtown, New York, on October 21, 2020. 20 21 Legislators In Attendance: 22 Presiding Officer Robert Calarco - District #7 23 Deputy Presiding Officer Kara Hahn - District #5 24 Legislator Anthony Piccirillo - District #8 25 Legislator Sam Gonzalez - District #9 26 Legislator Tom Cilmi - District #10 27 Legislator Steven Flotteron - District #11 28 Legislator Leslie Kennedy - District #12 29 Legislator Susan A. Berland - District #16 30 Legislator Tom Donnelly - District # 17 31 32 Also In Attendance: 33 Sarah Simpson - Counsel to the Legislature 34 Dan Dubois - Chief Deputy Clerk/Suffolk County Legislature 35 Lora Gellerstein - Chief of Staff/Presiding Officer's Office 36 Felicia Scocozza - Riverhead Community Awareness Program 37 Matt Kamper - Regional Director/Passengers United 38 Andrew Pollack - Public Advisor/Passengers United 39 Andy Quito - Passengers United 40 Ryan McGarry - Suffolk County AME 41 Gregory Noone - Thursday's Child 42 Allen Kovesdy 43 Yuki Endo 44 John Michno 45 All Other Interested Parties 46 47 Minutes Taken By: 48 Alison Mahoney - Court Stenographer 49 50 Transcript Prepared By: 51 Kim Castiglione - Legislative Secretary 52 53 54 55 56 * Index Included at End of Transcript 1 Public Hearing/2021 Operating Budget & SWSD Assessment Roll - 10/21/20 1 (*The meeting was called to order at 12:30 p.m.*) 2 3 (*The following testimony was taken by Alison Mahoney - 4 Court Stenographer & was transcribed by 5 Kim Castiglione - Legislative Secretary*) 6 7 P.O. -

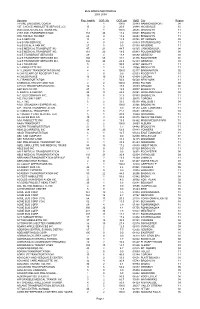

Operator Profile 2002 - 2003

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2002 - 2003 Operator .Insp 02-03 .OOS 02-03 OOS Rate 02-03 OpID City Region 112 LIMOUSINE INC. 2 0 0.0 28900 CENTER MORICHES 10 1ST. CHOICE AMBULETTE SERVICE LCC 1 0 0.0 29994 HICKSVILLE 10 2000 ADVENTURES & TOURS INC 5 2 40.0 26685 BROOKLYN 11 217 TRANSPORTATION INC 5 1 20.0 24555 STATEN ISLAND 11 21ST AVE. TRANSPORTATION 201 30 14.9 03531 BROOKLYN 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 57 4 7.0 06043 BROOKLYN 11 A & A ROYAL BUS COACH CORP. 1 1 100.0 30552 MAMARONECK 08 A & A SERVICE 17 3 17.6 05758 MT. VERNON 08 A & B VAN SERVICE 4 1 25.0 03479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & B'S DIAL A VAN INC. 23 1 4.3 03339 ROCKAWAY BEACH 11 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC 60 16 26.7 06165 CANANDAIGUA 04 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC. 139 29 20.9 05943 POUGHKEEPSIE 08 A & E TRANSPORT 4 0 0.0 05508 WATERTOWN 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES 39 1 2.6 06692 OSWEGO 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC 154 25 16.2 24376 ROCHESTER 04 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 191 35 18.3 02303 OSWEGO 03 A 1 AMBULETTE INC 9 0 0.0 20066 BROOKLYN 11 A 1 LUXURY TRANSPORTATION INC. 4 2 50.0 02117 BINGHAMTON 02 A CHILDCARE OF ROOSEVELT INC. 5 1 20.0 03533 ROOSEVELT 10 A CHILD'S GARDEN DAY CARE 1 0 0.0 04307 ROCHESTER 04 A CHILDS PLACE 12 7 58.3 03454 CORONA 11 A J TRANSPORTATION 2 1 50.0 04500 NEW YORK 11 A MEDICAL ESCORT AND TAXI 2 2 100.0 28844 FULTON 03 A&J TROUS INC. -

Classic Coach Acquires Hampton Luxury Liner Campolo Middleton Advises the Purchaser

For Immediate Release Contact: Joseph Campolo David Pinkowitz Campolo Middleton & Associates DCP Marketing Services LLC 631-738-9100 631-491-5343 [email protected] [email protected] Classic Coach acquires Hampton Luxury Liner Campolo Middleton Advises the Purchaser Bohemia, NY – Campolo, Middleton & Associates, LLP, a leading full-service Long Island law firm, has announced that it provided legal and advisory services to Classic Coach, the Bohemia- based ground charter service, in its recent acquisition of Hampton Luxury Liner. Details of the transaction were not disclosed, other than to describe it as "a multi-million dollar investment in the Hamptons travel market." The transaction puts Classic Coach in direct competition with Hampton Jitney, the Southampton service that carries passengers between New York City and the Hamptons. Classic Coach's schedule will include six daily roundtrips with its 55-seat luxury coaches that include DirectTV and Internet service. "The transaction was relatively straightforward," said Joe Campolo, partner at Campolo Middleton. "Both parties and our law firm are very experienced in the transportation business, so there were not many surprises. We worked hard on the details, did some tough negotiating, and got the deal done in record time." "Adding the Hamptons run gives our company a broader customer base," said Bill Schoolman, President of Classic Coach." Since 2002, we've tripled our revenue in motor coach charters between Long Island and Atlantic City. We also have a good share of the New York metro charter market, with many high school clubs, senior travel groups, and tour operators as customers. This acquisition helps round out our market base." About Campolo Middleton & Associates LLP Located in the heart of Long Island, Campolo, Middleton & Associates, LLP is a full- service law firm with the expertise and experience to represent clients in a wide variety of legal matters. -

Effective Strategies for Congestion Management

EFFECTIVE PRACTICES FOR CONGESTION MANAGEMENT: FINAL REPORT Requested by: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Prepared by: Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Cambridge, MA Resource Systems Group, Inc. Burlington, VT November 2008 The information contained in this report was prepared as part of NCHRP Project 20-24(63), National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Transportation Research Board. Acknowledgements This study was requested by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), and conducted as part of National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Project 20-24. The NCHRP is supported by annual voluntary contributions from the state Departments of Transportation (DOTs). Project 20-24 is intended to fund studies of interest to the leadership of AASHTO and its member DOTs. Christopher Porter of Cambridge Systematics was the lead author of the report, working with John Suhrbier of Cambridge Systematics and Peter Plumeau and Erica Campbell of Resource Systems Group. The work was guided by a task group chaired by Constance Sorrell which included Daniela Bremmer, Mara Campbell, Ken De Crescenzo, Eric Kalivoda, Ronald Kirby, Sheila Moore, Michael Morris, Janet Oakley, Gerald Ross, Steve Simmons, Dick Smith, Kevin Thibault, Mary Lynn Tischer, and Robert Zerrillo. The project was managed by Andrew C. Lemer, Ph. D., NCHRP Senior Program Officer. Disclaimer The opinions and conclusions expressed or implied are those of the research agency that performed the research and are not necessarily those of the Trans- portation Research Board or its sponsors. The information contained in this document was taken directly from the submission of the author(s). This docu- ment is not a report of the Transportation Research Board or of the National Research Council. -

S66 Passengers

Suffolk County Transit Bus Information Suffolk County Transit Fares & Information Effective January 1, 2021 Questions, Suggestions, Complaints? Full fare $2.25 Call Suffolk County Transit Information Service Youth/Student fare $1.25 Youths 5 to 13 years old 7 DAY SERVICE 631.852.5200 Students 14 to 22 years old (High School/College ID required). Monday to Friday 8:00am to 4:30pm Children under 5 years old FREE SCHEDULE Limit 3 children accompanied by adult. Senior, Person with Disabilities, Medicare Care Holders and Suffolk County Veterans 75 cents SCAT Paratransit Service Personal Care Attendant FREE Paratransit Bus Service is available to ADA eligible When traveling to assist passenger with disabilities. S66 passengers. To register or for more information, Transfer 25 cents call Office for People with Disabilities at 631.853.8333. Available on request when paying fare. Good for two (2) connecting buses. Patchogue to Riverhead Valid for two (2) hours from time received. Large Print/Spanish Bus Schedules Not valid for return trip. Patchogue to Ctr. Moriches To obtain a large print copy of this or other Suffolk Special restrictions may apply (see transfer). County Transit bus schedules, call 631.852.5200 Passengers Please or visit www.sct-bus.org. •Passengers must deposit their own fare. Serving Para obtener una copia en español de este u otros •Arrive earlier than scheduled departure time. Patchogue Railroad horarios de autobuses de Suffolk County Transit, •Tell driver your destination. llame al 631.852.5200 o visite www.sct-bus.org. •SCT Drivers announce Major Bus Stop locations. East Patchogue • Smoking, drinking, eating & playing radios prohibited on buses. -

Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development

Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development final memorandum prepared for New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Greater Bridgeport Regional Planning Agency South Western Regional Planning Agency prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. with Eng-Wong Taub & Associates Howard/Stein-Hudson Associates, Inc. Gruzen Samton Architects, Planners & Int. Designers HydroQual Inc. M.G. McLaren, PC Management and Transportation Associates, Inc. STV, Inc. September 30, 2003 www.camsys.com final technical memorandum Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Task 2 – Baseline Data for Transportation Plan Development prepared for New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Greater Bridgeport Regional Planning Agency South Western Regional Planning Agency prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Eng-Wong Taub & Associates Howard/Stein-Hudson Associates, Inc. Gruzen Samton Architects, Planners & Int. Designers HydroQual Inc. M.G. McLaren, PC Management and Transportation Associates, Inc. STV, Inc. September 30, 2003 Long Island Sound Waterborne Transportation Plan Technical Memorandum for Task 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction.................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Purpose and Need.................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2 The National Policy Imperative .......................................................................... -

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2003-2004 Operator Reg Inspno

BUS OPERATOR PROFILE 2003-2004 Operator Reg_InspNo OOS_No OOS_pct OpID City Region 18 VINE LIMOUSINE COACH 1 1 100.0 36889 HAMMONDSPORT 04 1ST. CHOICE AMBULETTE SERVICE LCC 15 3 20.0 29994 HICKSVILLE 10 2000 ADVENTURES & TOURS INC 1 1 100.0 26685 BROOKLYN 11 21ST AVE. TRANSPORTATION 183 26 14.2 03531 BROOKLYN 11 3RD AVENUE TRANSIT 66 9 13.6 06043 BROOKLYN 11 A & A SERVICE 14 2 14.3 05758 MT VERNON 08 A & B VAN SERVICE 4 0 0.0 03479 STATEN ISLAND 11 A & B'S DIAL A VAN INC. 27 0 0.0 03339 ARVERNE 11 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC 47 21 44.7 06165 CANANDAIGUA 04 A & E MEDICAL TRANSPORT INC. 161 29 18.0 05943 POUGHKEEPSIE 08 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES 29 4 13.8 06692 OSWEGO 03 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC 160 55 34.4 24376 ROCHESTER 04 A & E TRANSPORT SERVICES INC. 192 44 22.9 02303 OSWEGO 03 A & J TOURS INC 5 4 80.0 27937 HEWLITT 11 A 1 AMBULETTE INC 8 1 12.5 20066 BROOKLYN 11 A 1 LUXURY TRANSPORTATION INC. 4 4 100.0 02117 BINGHAMTON 02 A CHILDCARE OF ROOSEVELT INC. 2 0 0.0 03533 ROOSEVELT 10 A CHILDS PLACE 13 10 76.9 03454 CORONA 11 A J TRANSPORTATION 2 1 50.0 04500 NEW YORK 11 A MEDICAL ESCORT AND TAXI 2 2 100.0 28844 FULTON 03 A PLUS TRANSPORTATION INC. 16 6 37.5 33889 ARMONK 08 A&P BUS CO INC 27 5 18.5 29007 BROOKLYN 11 A. -

Transportation & Infrastructure

Southold Town Comprehensive Plan Update Transportation & Infrastructure Draft September 19, 2018 Updated February 21, 2019 (in collaboration with AKRF, Inc.) This document was prepared for the New York State Department of State with funds provided under Title 11 of the Environmental Protection Fund. Transportation & Infrastructure TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary and Introduction............................................................................................... TRANSPORTATION Inventory of Transportation Systems ................................................................................................ Assessment of Future Transportation Needs and Opportunities ....................................................... Transportation System Goals ............................................................................................................ LIST OF TABLES 1. Average Annual Daily Traffic - Routes 25 and 48 ....................................................................... LIST OF FIGURES 1. Streets in the Town of Southold by Ownership ............................................................................ 2. Percent of Sidewalk Miles in the Town of Southold by Hamlet ................................................... 3. Gaps in Sidewalk Network in Town of Southold ......................................................................... 4. Percent of Multi-Use Path Miles by Hamlet in Town of Southold ............................................... 5. Bicycle Routes in the Town of Southold .....................................................................................