Gambling on a Gambler: High Stakes for the Philippine Presidency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

People Power II in the Philippines: the First E-Revolution?

People Power II in the Philippines: The First E-Revolution? Julius Court With the new Century over a year old, technology has now played critical yet very different roles in bringing two of the world’s leaders to power. Among others things, Florida will remembered for technological hitches that plagued the ballot counting and possibly pushed the outcome of the U.S. election in favor of George W. Bush. On the other hand, a new information and communications technology (ICT) - the mobile phone - was the symbol of the People Power II revolution in the Philippines. Arguably, the most lasting image of Ms Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s new Presidency was when, on being asked in a news conference whether a Lt. Gen. Espinosa was planning a coup, she called him up on her mobile phone. In moment of high drama she asked him directly if this was the case and after a brief conversation reported it wasn’t. But it was the use of cellphones for “texting” rather than calls that was the most intriguing part of People Power II and was also the key to its success. The lack of attention to the role of technology is surprising. People Power II was arguably the world’s first “E-revolution” - a change of government brought about by new forms of ICTs. “Texting” allowed information on former President Estrada’s corruption to be shared widely. It helped facilitate the protests at the EDSA shrine at a speed that was startling - it took only 88 hours after the collapse of impeachment to remove Estrada. -

Pacnet Number 23 May 6, 2010

Pacific Forum CSIS Honolulu, Hawaii PacNet Number 23 May 6, 2010 Philippine Elections 2010: Simple Change or True problem is his loss of credibility stemming from his ouster as Reform? by Virginia Watson the country’s president in 2001 on charges of corruption. Virginia Watson [[email protected]] is an associate Survey results for vice president mirror the presidential professor at the Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies in race. Aquino’s running mate, Sen. Manuel Roxas, Jr. has Honolulu. pulled ahead with 37 percent. Sen. Loren Legarda, in her second attempt at the vice presidency, dropped to the third On May 10, over 50 million Filipinos are projected to cast spot garnering 20 percent, identical to the results of the their votes to elect the 15th president of the Philippines, a Nacionalista Party’s presidential candidate, Villar. Estrada’s position held for the past nine years by Gloria Macapagal- running mate, former Makati City Mayor Jejomar “Jojo” Arroyo. Until recently, survey results indicated Senators Binay, has surged past Legarda and he is now in second place Benigno Aquino III of the Liberal Party and Manuel Villar, Jr. with 28 percent supporting his candidacy. of the Nacionalista Party were in a tight contest, but two weeks from the elections, ex-president and movie star Joseph One issue that looms large is whether any of the top three Estrada, of the Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino, gained ground to contenders represents a new kind of politics and governance reach a statistical tie with Villar for second place. distinct from Macapagal-Arroyo, whose administration has been marked by corruption scandals and human rights abuses Currently on top is “Noynoy” Aquino, his strong showing while leaving the country in a state of increasing poverty – the during the campaign primarily attributed to the wave of public worst among countries in Southeast Asia according to the sympathy following the death of his mother President Corazon World Bank. -

Philippines Stop Torture Npm Bill Action May 2016 Asa 28

PHILIPPINES STOP TORTURE NPM BILL ACTION MAY 2016 ASA 28/3983/2016 BACKGROUND Torture at the hands of the police in the Philippines continues with alarming frequency while those responsible are almost always allowed to evade justice. Over a year after our report, Above the law: Police Torture in the Philippines was published, very little has changed – police torture is still rampant across the country with impunity, and only one perpetrator, police officer Jerick Dee Jimenez, has been convicted since the enactment of a landmark anti-torture law in 2009. As per its obligations under the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture, the Philippines should have put the establishment of a National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) for torture in place by April 2013. A NPM bill is currently filed before the Senate and the Philippine government has an opportunity to pass this bill. It’s high time this is done. We are urging the Senate to immediately establish the NPM which is currently filed before both the Congress and Senate, and to ensure regular meetings of the Oversight Committee as provided by the Anti-Torture Law Act to ensure that there are genuine criminal investigations in torture cases by police. GOAL The Philippine Senate passes the NPM bill in order to adequately address torture by police authorities, with a view to bringing perpetrators to justice and preventing further use of torture and other ill-treatment. TARGETS We are targeting eight senators who will be returning to the Senate after May 2016 elections including the current Senate President, Senator Franklin Drilon. -

The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada

International Bulletin of Political Psychology Volume 5 Issue 3 Article 1 7-17-1998 From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada IBPP Editor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp Part of the International Relations Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Editor, IBPP (1998) "From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada," International Bulletin of Political Psychology: Vol. 5 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/ibpp/vol5/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Bulletin of Political Psychology by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editor: From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada International Bulletin of Political Psychology Title: From the Movies to Malacañang: The Rise to Power of Philippine President Joseph Estrada Author: Elizabeth J. Macapagal Volume: 5 Issue: 3 Date: 1998-07-17 Keywords: Elections, Estrada, Personality, Philippines Abstract. This article was written by Ma. Elizabeth J. Macapagal of Ateneo de Manila University, Republic of the Philippines. She brings at least three sources of expertise to her topic: formal training in the social sciences, a political intuition for the telling detail, and experiential/observational acumen and tradition as the granddaughter of former Philippine president, Diosdado Macapagal. (The article has undergone minor editing by IBPP). -

Philhealth Officials Not Yet Off the Hook — DOJ

Headline PhilHealth officials not yet off the hook — DOJ MediaTitle Philippine Star(www.philstar.com) Date 14 Jun 2019 Section NEWS Order Rank 1 Language English Journalist N/A Frequency Daily PhilHealth officials not yet off the hook — DOJ MANILA, Philippines — Officials of the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. (PhilHealth) are not yet off the hook in the allegedly anomalous payment of claims benefits to “ghost” patients of a dialysis treatment center, Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra said yesterday. Guevara said the resignation of PhilHealth board members earlier this week did not clear them of possible liabilities for the controversy that reportedly cost the government P100 billion. He said the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) is now looking into the criminal liabilities of the PhilHealth executives. “The NBI is looking into the possibility that certain PhilHealth officials may be charged for violation of the Anti-Graft Law if they knowingly participated in this allegedly fraudulent scheme and benefitted from it,” Guevarra said. After meeting with President Duterte earlier this week, PhilHealth officials led by president and chief executive officer Roy Ferrer tendered their courtesy resignations. The six other officials who resigned were Jack Arroyo, elected local chief executive; Rex Maria Mendoza, independent director of the Monetary Board; Hildegardes Dineros of the information economy sector; Celestina Ma. Jude dela Serna of the Filipino overseas workers sector; Roberto Salvador of the formal economy sector and Joan Cristine Reina Liban-Lareza of the health care provider sector. The NBI filed charges of estafa and falsification of documents against officers of WellMed Dialysis and Laboratory Center led by its owner Bryan Sy before the Department of Justice (DOJ) earlier this week. -

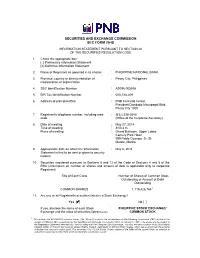

Definitive Information Statement

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 20-IS INFORMATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 20 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE 1. Check the appropriate box: [ ] Preliminary Information Statement [X] Definitive Information Statement 2. Name of Registrant as specified in its charter : PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK 3. Province, country or other jurisdiction of : Pasay City, Philippines incorporation or organization 4. SEC Identification Number : AS096-005555 5. BIR Tax Identification Number : 000-188-209 6. Address of principal office : PNB Financial Center President Diosdado Macapagal Blvd. Pasay City 1300 7. Registrant’s telephone number, including area : (632) 536-0540 code (Office of the Corporate Secretary) 8. Date of meeting : May 27, 2014 Time of meeting : 8:00 a.m. Place of meeting : Grand Ballroom, Upper Lobby Century Park Hotel 599 Pablo Ocampo, Sr. St. Malate, Manila 9. Approximate date on which the Information : May 6, 2014 Statement is first to be sent or given to security holders 10. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the Code or Sections 4 and 8 of the RSA (information on number of shares and amount of debt is applicable only to corporate Registrant): Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Common Stock Outstanding or Amount of Debt Outstanding COMMON SHARES 1,119,426,7641/ 11. Are any or all Registrant’s securities listed in a Stock Exchange? Yes [9] No [ ] If yes, disclose the name of such Stock : PHILIPPINE STOCK EXCHANGE/ Exchange and the class of securities listed therein COMMON STOCK 1/ This includes the 423,962,500 common shares (the “Shares”) issued to the stockholders of Allied Banking Corporation (ABC) relative to the merger of PNB and ABC as approved by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on January 17, 2013. -

MDG Report 2010 WINNING the NUMBERS, LOSING the WAR the Other MDG Report 2010

Winning the Numbers, Losing the War: The Other MDG Report 2010 WINNING THE NUMBERS, LOSING THE WAR The Other MDG Report 2010 Copyright © 2010 SOCIAL WATCH PHILIPPINES and UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (UNDP) All rights reserved Social Watch Philippines and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) encourage the use, translation, adaptation and copying of this material for non-commercial use, with appropriate credit given to Social Watch and UNDP. Inquiries should be addressed to: Social Watch Philippines Room 140, Alumni Center, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, PHILIPPINES 1101 Telefax: +63 02 4366054 Email address: [email protected] Website: http://www.socialwatchphilippines.org The views expressed in this book are those of the authors’ and do not necessarily refl ect the views and policies of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Editorial Board: LEONOR MAGTOLIS BRIONES ISAGANI SERRANO JESSICA CANTOS MARIVIC RAQUIZA RENE RAYA Editorial Team: Editor : ISAGANI SERRANO Copy Editor : SHARON TAYLOR Coordinator : JANET CARANDANG Editorial Assistant : ROJA SALVADOR RESSURECCION BENOZA ERICSON MALONZO Book Design: Cover Design : LEONARD REYES Layout : NANIE GONZALES Photos contributed by: Isagani Serrano, Global Call To Action Against Poverty – Philippines, Medical Action Group, Kaakbay, Alain Pascua, Joe Galvez, Micheal John David, May-I Fabros ACKNOWLEDGEMENT any deserve our thanks for the production of this shadow report. Indeed there are so many of them that Mour attempt to make a list runs the risk of missing names. Social Watch Philippines is particularly grateful to the United Nations Millennium Campaign (UNMC), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Millennium Development Goals Achievement Fund (MDG-F) and the HD2010 Platform for supporting this project with useful advice and funding. -

Social Climate/Column for Phil Daily Inquirer

“What’s the latest?” Page 1 of 3 Column for Philippine Daily Inquirer PDI 09-02, 1-09-08 [for publication on 1-10-2008] “What’s the latest?” Mahar Mangahas Right after greeting me Happy New Year, the most common next question of friends and acquaintances is “What’s the latest?” referring, most of all, to prospects for the next national election in 2010, according to the SWS surveys. I tell them that the survey leaders are a cluster of three, namely Noli de Castro, Manny Villar, and Loren Legarda, and then refer them to the SWS website, since I can’t remember so many numbers, all the more as another year passes by. Anyway, for the nth time, last November 7th SWS reported the finding of its September 2008 survey that the top answers to the question on persons who would be good (magaling) successors of Pres. Arroyo as President, with up to three names accepted, were – with percentages in parentheses -- de Castro (29), Villar (28), Legarda (26), Panfilo Lacson (17), Francis Escudero (16), Joseph Estrada (13), and Mar Roxas (13). All others, including Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, Bayani Fernando, Antonio Trillanes et al., got one percent or less. In short, the aspirants cluster into three groups: the top three, then a group of four at least 9 points away, and then everyone else. To be fair to all possible aspirants, no list of names was provided to prompt the respondents. As a result, we discover that some Filipinos favor the return of GMA or Erap in 2010, and some favor Trillanes, though he would not yet be 40 years old by then. -

'Sin' Tax Bill up for Crucial Vote

Headline ‘Sin’ tax bill up for crucial vote MediaTitle Manila Standard Philippines (www.thestandard.com.ph) Date 03 Jun 2019 Section NEWS Order Rank 6 Language English Journalist N/A Frequency Daily ‘Sin’ tax bill up for crucial vote Advocates of a law raising taxes on cigarettes worried that heavy lobbying by tobacco companies over the weekend could affect the vote in the Senate Monday. Former Philhealth director Anthony Leachon and UP College of Medicine faculty member Antonio Dans said a failure of the bill to pass muster would deprive the government’s Universal Health Care program of funding. “Definitely, the lobbying can affect how our senators will behave... how they will vote,” said Leachon, also chairman of the Council of Past Presidents of the Philippine College of Physicians. But Leachon and Dans said they remained confident that senators who supported the sin tax law in 2012 would support the new round of increases on cigarette taxes. These were Senate Minority Leader Franklin Drilon, Senators Panfilo Lacson, Francis Pangilinan, Antonio Trillanes IV and re-elected Senator Aquilino Pimentel III. They are also hopeful that the incumbent senators who voted against the increase in the excise taxes on cigarettes in 2012—Senate President Vicente Sotto III, Senate Pro Tempore Ralph Rectp and outgoing Senators Francis Escudero and Gregorio Honasan—would have a change of heart. While Pimentel, who ran in the last midterm elections, supported the increase in tobacco taxes in 2012, he did not sign Senator Juan Edgardo Angara’s committee report, saying the bill should be properly scrutinized as it might result in the death of the tobacco industry. -

$,Uprcme Qcourt Jlllanila

SUPRE~.4E COU"T OF M PHII..IPPINES PIJi,UC 1HfOl'll.fA1'1oti OfF!CE 31\epublic of tbe l)bilippineg $,Uprcme QCourt Jlllanila EN BANC SENATORS FRANCIS "KIKO" N. G.R. No. 238875 PANGILINAN, FRANKLIN M. DRILON, PAOLO BENIGNO "BAM" AQUINO :CV, LEILA M. DE LIMA, RISA HONTIVEROS, AND ANTONIO 'SONNY' F. TRILLANES IV, Petitioners, -versus- ALAN PETER S. CAYETANO, SALVADOR C. MEDIALDEA, TEODORO L. LOCSIN, JR., AND SALVADOR S. PANELO, Respondents. x-------------------------------------------x x----- -------------------------------------x PHILIPPINE COALITION FOR G.R. No. 239483 THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT (PCICC), LORETTA ANN P. ROSALES, DR. AURORA CORAZON A. PARONG, EVELYN BALAIS- SERRANO, JOSE NOEL D. OLANO, REBECCA DESIREE E. LOZADA, ED ELIZA P. HERNANDEZ, ANALIZA T. UGAY, NIZA - CONCEPCION ARAZAS, GLORIA ESTER CATIBAYAN-GUARIN, RAY PAOLO "ARPEE" J. SANTIAGO, GILBERT TERUEL ANDRES, AND AXLE P. SIMEON, Petitioners, I Decision ' 2 G.R. Nos. 238875, 239483, and 240954 ::'j·' . -., . ',' : t -versus- I-••,:•:••.·,., OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY, REPRESENTED BY HON. SALVADOR MEDIALDEA, THE DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS, REPRESENTED BY HON. ALAN PETER CAYETANO, AND THE PERMANENT MISSION OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES TO THE UNITED NATIONS, REPRESENTED BY HON. TEODORO LOCSIN, JR., Respondents. x-------------------------------------------x x-------------------------------------------x INTEGRATED BAR OF THE G.R. No. 240954 PHILIPPINES, Petitioner, Present: PERALTA, ChiefJustice, -versus- PERLAS-BERNABE, LEONEN, CAGUIOA, GESMUNDO, OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE HERNANDO, SECRETARY, REPRESENTED CARANDANG, BY HON. SALVADOR C. LAZARO-IAVIER, MEDIALDEA, THE INTING, DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN ZALAMEDA, AFFAIRS, REPRESENTED BY LOPEZ, M., HON. ALAN PETER CAYETANO DELOS SANTOS, AND THE PERMANENT GAERLAN, MISSION OF THE REPUBLIC OF ROSARIO, and THE PHILIPPINES TO THE LOPEZ, J., JJ UNITED NATIONS, REPRESENTED · BY HON. -

Free the the Department of Justice Has Already Submitted Its Health Workers Is Another Day Recommendations Regarding the Case of the 43 Health Workers

Another day in prison for the and their families tormented. FREE THE The Department of Justice has already submitted its health workers is another day recommendations regarding the case of the 43 health workers. The President himself has admitted that the that justice is denied. search warrant was defective and the alleged evidence President Benigno Aquino III should act now against the Morong 43 are the “fruit of the poisonous for the release of the Morong 43. tree.” Various local and international organizations Nine months ago in February, the 43 health workers have called for the health workers’ release. including 26 women – two of whom have already given When Malacañang granted amnesty to rebel birth while in prison – were illegally arrested, searched, soldiers, many asked why the Morong 43 remained 43! detained, and tortured. Their rights are still being violated in prison. We call on the Aquino government to withdraw the charges against the Morong 43 and release them unconditionally! Most Rev. Antonio Ledesma, Archbishop, Metropolitan Archdiocese of CDO • Atty. Roan Libarios, IBP • UN Ad Litem Judge Romeo Capulong • Former SolGen Atty. Frank Chavez • Farnoosh Hashemian, MPH, Nat’l Lawyers Guild • Rev. Nestor Gerente, UMC, CA • Danny Bernabe, Echo Atty. Socorro Eemac Cabreros, IBP Davao City Pres. (2009) • Atty. Federico Gapuz, UPLM • Atty. Beverly Park UMC • J. Luis Buktaw, UMC LA, CA • Sr. Corazon Demetillo, RGS • Maria Elizabeth Embry, Antioch Most Rev. Oscar Cruz, Archbishop Emeritus, Archdiocese of Lingayen • Most Selim-Musni • Atty. Edre Olalia, NUPL • Atty. Joven Laura, Atty. Julius Matibag, NUPL • Atty. Ephraim CA • Haniel Garibay, Nat’l Assoc.