Briefing Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Re: Terrorist Attacks on September 11, 2001

Case 1:03-md-01570-GBD-SN Document 3671 Filed 08/01/17 Page 1 of 33 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ____________________________________ ) IN RE: TERRORIST ATTACKS ON ) Civil Action No. 03 MDL 1570 (GBD) SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 ) ECF Case ____________________________________ ) This document relates to: Ashton, et al. v. al Qaeda, et al., No. 02-cv-6977 Federal Insurance Co., et al. v. al Qaida, et al., No. 03-cv-6978 Thomas Burnett, Sr., et al. v. Al Baraka Inv. & Dev. Corp., et al., No. 03-cv-9849 Continental Casualty Co., et al. v. Al Qaeda, et al., No. 04-cv-5970 Cantor Fitzgerald Assocs., et al. v. Akida Inv. Co., et al. No. 04-cv-7065 Euro Brokers Inc., et al. v. Al Baraka Inv. & Dev. Corp., et al., No. 04-cv-7279 McCarthy, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, No. 16-cv-8884 Aguilar, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 16-cv-9663 Addesso, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 16-cv-9937 Hodges, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 17-cv-117 DeSimone v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, No. 17-cv-348 Aiken, et al v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 17-cv-450 The Underwriting Members of Lloyd’s Syndicate 53, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 17-cv-2129 The Charter Oak Fire Insurance Co., et al. v. Al Rajhi Bank, et al. No. 17-cv-02651 Abarca, et al. -

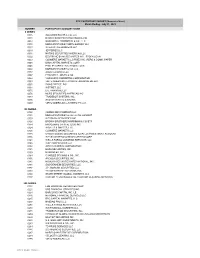

Tenant Listing Report World Trade Center Lease / Space Reports As of October 26, 2000

TENANT LISTING REPORT WORLD TRADE CENTER LEASE / SPACE REPORTS AS OF OCTOBER 26, 2000 Lease Lease Tenant Name Bldg Floor Suite # Start Date End Date LANDMARK EDUCATION CORPORATION 1WTC 7 118 11/23/1998 6/23/2014 BANK OF AMERICA CORP. 1WTC 9 901 10/8/1993 6/30/2010 BANK OF AMERICA CORP. 1WTC 10 1001 12/5/1993 6/30/2010 TES (USA) CORPORATION 1WTC 11 1147 12/1/1999 11/30/2004 TES (U.S.A.) CORPORATION 1WTC 11 1147 8/1/1994 11/30/1999 ALLSTATE INSURANCE CO. 1WTC 11 1145 1/4/1996 12/31/2000 CANDIA SHIPPING (USA) INC. 1WTC 11 1111 7/1/1998 2/28/1999 PORCELLA, VICINI & CO., INC. 1WTC 11 1151 5/1/1999 4/30/2004 BANK OF AMERICA CORP. 1WTC 11 1115 11/19/1993 6/30/2010 SYNS TECHNOLOGIES, INC 1WTC 11 103 8/1/1997 7/31/1999 JAMES R. TUCKER 1WTC 11 1153 10/27/1997 10/26/2000 PRIMARK DECISION ECONOMICS, IN 1WTC 11 1109 5/15/1999 5/14/2009 M.J. BRUDERMAN & COMPANY, INC. 1WTC 11 1155 5/16/1999 5/15/2002 BANK OF AMERICA CORP. 1WTC 12 1201 9/13/1993 6/30/2010 BANK OF AMERICA CORP. 1WTC 13 1301 4/8/1994 6/30/2010 BANK OF AMERICA CORP. 1WTC 14 1401 10/7/1994 6/30/2010 LANDMARK EDUCATION CORPORATION 1WTC 15 1501 11/23/1998 6/23/2013 ZIM-AMERICAN ISRAELI SHIPPING 1WTC 16 1601 3/1/1996 2/28/2006 EMPIRE BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD 1WTC 17 1701 12/10/1997 12/31/2018 BANK OF AMERICA CORP. -

Recollections & Reflections of 9/11/01

PERSPECTIVE Recollections & Reflections of 9/11/01 Shown above: 2020 Tribute. [NATIONAL SEPTEMBER 11 MEMORIAL & MUSEUM; WWW.911MEMORIAL.ORG] Cover photo: Tribute in Light is a commemorative public art installation first presented six months after 9/11 and then every year thereafter, from dusk to dawn, on the night of September 11. [CREATIVE COMMONS, WIKIMEDIA] The Community Plaza in front of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum (more frequently known simply, as the 9/11 Memorial) at Ground Zero. [NATIONAL SEPTEMBER 11 MEMORIAL & MUSEUM; WWW.911MEMORIAL.ORG] Memorial photograph wall of people killed on display at the World Trade Center Memorial and Museum in New York City, built on the site of the terrorist attack that brought down the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers on 9/11/2001. [LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, HIGHSMITH, CAROL M., PHOTOGRAPHER] RIMJ ARCHIVES | SEPTEMBER ISSUE WEBPAGE | RIMS SEPTEMBER 2021 RHODE ISLAND MEDICAL JOURNAL 73 PERSPECTIVE September 11, 2001 – A Recollection of a Tragic Day in my Hometown KENNETH S. KORR, MD, FACC New York City fire fighters amid debris at the World Trade Center. [LIBRARY OF CONGRESS] Two men assisting and walking with an injured woman down a street littered with paper and ashes, follow- ing the attack. [LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PHOTOGRAPHER DON HALASY] New York City fire fighter and another man covering his eyes on street in front of burning buildings following the Sept. 11th ter- rorist attack on the World Trade Center. [LIBRARY OF CONGRESS] IT WAS A TYPICAL HECTIC MONDAY IN THE hit. Something was going on in a field in NYC had to be evacuated. -

CANTOR FITZGERALD Charity Day

CANTOR FITZGERALD CHARITY DAY Tuesday September 11, 2018 Robert DeNiro New York City 2017 Cantor Charity Day Cantor Fitzgerald and our affiliate BGC Partners commemorate Ambassadors included: our 658 friends and colleagues and 61 Eurobrokers employees who perished in the September 11, 2001 World Trade Center Bill Clinton Karolina Kurkova attacks by donating 100% of our global revenues on Charity David Costabile Kevin Shattenkirk Dionne Warwick Kristen Davis Day to The Cantor Fitzgerald Relief Fund and dozens of Dr. Ruth Westheimer Padma Lakshmi charities around the world. Gretchen Mol Petra Nemcova Henrik Lundqvist Robert DeNiro Charity Day, originally conceived as a way to raise money for Jake Gyllenhaal Rosie Perez Jeff Hornacek Steve Buschemi The Cantor Fitzgerald Relief Fund to assist the families of Jenny McCarthy Tony Danza Cantor employees who lost their lives on 9/11, has expanded Karina Smirnoff Uzo Aduba to embrace charitable causes around the world. To date, Charity Day has raised $147 million. On Charity Day, participating charities bring celebrity “ambassadors” who join us on our trading floor to conduct trades over the phone with clients. Many distinguished guests have lent their support by joining us on this day, including prominent actors, musicians, sports icons, models, media personalities, royalty and politicians. Bill Clinton FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Who is Cantor Fitzgerald? Cantor Fitzgerald, a leading global financial services group at the forefront of CANTOR financial and technological innovation has been a proven and resilient leader for over 65 years. Cantor is a preeminent investment bank serving more than 7,000 institutional clients around the world, recognized for its strengths in fixed income and equity capital markets, investment banking, prime brokerage, and commercial real estate finance and for its global distribution platform. -

A Story of Rebuilding

A Story of Rebuilding An Interview with Howard W. Lutnick, Chairman and Chief Executive Offi cer, Cantor Fitzgerald, L.P. and BGC Partners, Inc. EDITORS’ NOTE In addition to his The markets are uneven with big trophies that are targets of the giant in- leadership of Cantor Fitzgerald, great opportunity and substantial risk vestment banks. Our aspiration was and is to Howard Lutnick is also Chairman coexisting. transact for our clients and to excel in serving and Chief Executive Offi cer of lead- The low interest rate environ- the middle market. ing global brokerage company, ment has made certain businesses That model requires us to have a much BGC Partners, Inc. He also served more viable and attractive than oth- larger sales force than the largest fi nancial fi rms, as Chairman, President, and CEO erwise would be the case, and at the because Cantor’s strength in distribution means of eSpeed, Inc., which merged with same time has constrained other busi- we bring value to both sides of a transaction. BGC in 2008. Lutnick guided the nesses. That cannot be a long-term We’re not in the business of taking risk and hop- rebuilding and growth of Cantor equilibrium. ing the markets go up. Our business is servicing Fitzgerald following the firm’s With the kind of issuance and our clients and meeting their needs, not trading tragic losses in the 9/11World Trade debt the country has, how can interest for ourselves or against them. Center attacks, and its care and Howard W. Lutnick rates not explode higher? They will, Therefore, we weren’t trying to market se- support of the families of its 658 em- eventually. -

Cantor Fitzgerald Charity Day

CANTOR FITZGERALD CHARITY DAY Wednesday September 11, 2019 Alec Baldwin at Cantor’s 2018 Charity Day New York City 2018 Cantor Charity Day Cantor Fitzgerald and our affiliates, BGC Partners and GFI Ambassadors included: Group, commemorate the 658 colleagues and 61 Eurobrokers Alec Baldwin John O’Hurley employees who perished in the September 11, 2001 World Amber Heard Kate Snow Billy Crudup Ken Daneyko Trade Center attacks by donating 100% of our global revenues Calvin Johnson Kevin Shattenkirk on Charity Day to the Cantor Fitzgerald Relief Fund and Carol Alt Kimiko Glenn Chad Cascadden LaChanze Sapp-Gooding dozens of charities around the world. Chris Cuomo Len Elmore Christopher Jackson Lucy Hale Common Melissa Rivers Charity Day, originally conceived as a way to raise money for the Curtis Martin Mike Breen Darryl Strawberry Neal Pionk Cantor Fitzgerald Relief Fund to assist the families of Cantor Dascha Polanco Nick Swisher David Muir Norah O’Donnell employees who lost their lives on 9/11, has expanded to David Robinson Petra Nemcova embrace charitable causes around the world. To date, Charity Don Mattingly President Bill Clinton Dr. Ruth Westheimer Richard Lui Day has raised $159 million. Enes Kanter Rosanna Scotto Evan Engram Rose Byrne Gayle King Rosie Perez On Charity Day, participating charities bring celebrity Gene Simmons Samantha Harris Goldie Hawn Saquon Barkley “ambassadors” who join us on our trading floor to conduct Gracie Carvalho Scarlett Fu Gretchen Mol Spencer Dinwiddie trades over the phone with clients. Many distinguished guests Jeffrey Ross Steve Buscemi have lent their support by joining us on this day, including Jenny McCarthy Tom Keene Jessica Pimentel Tony Blair prominent actors, musicians, sports icons, models, media Jim Leyritz Tony Danza Jimmy Vesey Victor Cruz personalities, royalty and politicians. -

It Began in 1897 As a Simple System for Holding Exams Without Proctors

The Myth of Martyrdom Good For Business Indie Innovator Challenging the conventional thinking Educating the next generation Putting the independence back about suicide bombers of executives and entrepreneurs into independent film The Magazine of Haverford College WINTER 2013 It began in 1897 as a simple system for holding exams without proctors. Since then, the cherished HONOR CODE has become the purest expression of the College’s values and an intrinsic part of a Haverford education. 9 20 Editor Contributing Writers DEPARTMENTS Eils Lotozo Charles Curtis ’04 Prarthana Jayaram ’10 Associate Editor Lini S. Kadaba 2 View from Founders Rebecca Raber Michelle Martinez 4 Letters to the Editor Graphic Design Alison Rooney Tracey Diehl, Louisa Shepard 6 Main Lines Justin Warner ’93 Eye D Communications 15 Faculty Profile Assistant Vice President for Contributing Photographers College Communications Thom Carroll 20 Mixed Media Chris Mills ’82 Dan Z. Johnson Brad Larrison 25 Ford Games Vice President for Josh Morgan 48 Roads Taken and Not Taken Institutional Advancement Michael Paras Michael Kiefer Josh Rasmussen 49 Giving Back/Notes From Zachary Riggins the Alumni Association 54 Class News 65 Then and Now On the cover: Photo by Thom Carroll Back cover photo: Courtesy of Haverford College Archives The Best of Both Worlds! Haverford magazine is now available in a digital edition. It preserves the look and page-flipping readability of the print edition while letting you search names and keywords, share pages of the magazine via email or social networks, as well as print to your personal computer. CHECK IT OUT AT haverford.edu/news/magazine.php Haverford magazine is printed on recycled paper that contains 30% post-consumer waste fiber. -

Michigan Today

Michigan Today . .Fall 2002 U-M Remembers Victims of 9/11/01 On the anniversary of the tragic events of Sept. 11, 2001, President Mary Sue Coleman helped dedicate a plaque honoring the 18 alumni/ae of the University who were among the terrorists' victims. "Even those of us who are new here, recalling our experience of the national trauma in other parts of the country, now share in the collective bereavement of the University of Michigan family," Coleman said to an overflow audience in the Alumni Center, which now houses the black granite memorial. "There are no words to describe the magnitude of our loss. They were vibrant, energetic, caring members of their communities, deeply involved with their friends and professional responsibilities." The following are brief sketches of those who died in the attacks: David Alger '68 MBA, president, Fred Alger Management, World Trade Center (WTC). Alger spoke at the Business School's commencement in 1997 and served on the University Investment Advisory Committee. Yeneneh Betru '95 MD, Medical Affairs Director Ð IPC, American Airlines Flight 77. Dr. Betru was a native of Ethiopia and grew up in Saudi Arabia. He specialized in improving hospital care and was in the process of developing an improved kidney dialysis machine. Brian Paul Dale '91 JD, senior consultant, Price Waterhouse, American Flight 11. Dale oversaw the legal and accounting activities at Blue Capital Management, the investment firm he co-founded. His job often required him to travel for business purposes. Paul Friedman '83 MSE, senior management consultant, Emergence Consulting, Flight 11. On the day before he boarded his flight from Boston, Friedman spent the day with his newly adopted infant son Richard "Rocky" Harry Hyun and took him to Starbucks. -

Numerical.Pdf

DTC PARTICPANT REPORT (Numerical Sort ) Month Ending - July 31, 2021 NUMBER PARTICIPANT ACCOUNT NAME 0 SERIES 0005 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO. LLC 0010 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO. 0013 SANFORD C. BERNSTEIN & CO., LLC 0015 MORGAN STANLEY SMITH BARNEY LLC 0017 INTERACTIVE BROKERS LLC 0019 JEFFERIES LLC 0031 NATIXIS SECURITIES AMERICAS LLC 0032 DEUTSCHE BANK SECURITIES INC.- STOCK LOAN 0033 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC/FIXED INC. REPO & COMM. PAPER 0045 BMO CAPITAL MARKETS CORP. 0046 PHILLIP CAPITAL INC./STOCK LOAN 0050 MORGAN STANLEY & CO. LLC 0052 AXOS CLEARING LLC 0057 EDWARD D. JONES & CO. 0062 VANGUARD MARKETING CORPORATION 0063 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU FINANCIAL BD LLC 0065 ZIONS DIRECT, INC. 0067 INSTINET, LLC 0075 LPL FINANCIAL LLC 0076 MUFG SECURITIES AMERICAS INC. 0083 TRADEBOT SYSTEMS, INC. 0096 SCOTIA CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0099 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU ITG LLC 100 SERIES 0100 COWEN AND COMPANY LLC 0101 MORGAN STANLEY & CO LLC/SL CONDUIT 0103 WEDBUSH SECURITIES INC. 0109 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO./ETF 0114 MACQUARIE CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0124 INGALLS & SNYDER, LLC 0126 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC 0135 CREDIT SUISSE SECURITIES (USA) LLC/INVESTMENT ACCOUNT 0136 INTESA SANPAOLO IMI SECURITIES CORP. 0141 WELLS FARGO CLEARING SERVICES, LLC 0148 ICAP CORPORATES LLC 0158 APEX CLEARING CORPORATION 0161 BOFA SECURITIES, INC. 0163 NASDAQ BX, INC. 0164 CHARLES SCHWAB & CO., INC. 0166 ARCOLA SECURITIES, INC. 0180 NOMURA SECURITIES INTERNATIONAL, INC. 0181 GUGGENHEIM SECURITIES, LLC 0187 J.P. MORGAN SECURITIES LLC 0188 TD AMERITRADE CLEARING, INC. 0189 STATE STREET GLOBAL MARKETS, LLC 0197 CANTOR FITZGERALD & CO. / CANTOR CLEARING SERVICES 200 SERIES 0202 FHN FINANCIAL SECURITIES CORP. 0221 UBS FINANCIAL SERVICES INC. -

Cantor Fitzgerald's Annual Charity

ABOUT CANTOR FITZGERALD’S CHARITY DAY Cantor Fitzgerald and our affiliate BGC Partners commemorate our 658 friends and colleagues and 61 Eurobrokers employees who perished in the September 11, 2001 World Trade Center attacks by donating 100% of our global revenues on Charity Day to The Cantor Fitzgerald Relief Fund and dozens of charities around the world. Charity Day, originally conceived as a way to raise money for The Cantor Fitzgerald Relief Fund to assist the families of Cantor employees who lost their lives on 9/11, has expanded to embrace charitable causes around the world. To date, Charity Day has raised approximately $137 million. On Charity Day, participating charities’ celebrity “ambassadors” come to our trading floor to Peyton Manning and Eli Manning conduct trades on the phone with clients. at Cantor’s Charity Day 2016 Many distinguished guests lent their support by joining us on the day. We were proud to welcome actors, musicians, sports icons, models, among many others, including: Ben Stiller Jamie Foxx Margot Robbie Brandon Marshall Jay Pharoah Mark Messier Ed Burns Jeremy Lin Mayor Rudy Giuliani Christy Turlington John Franco Michael J. Fox Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson Jon Bon Jovi Peyton Manning Darryl “DMC” McDaniels Julianna Margulies Uzo Aduba Dikembe Mutombo Kate Upton Vanessa Williams Eli Manning Kim Kardashian Venus Williams Eric Decker Lady Gaga Victor Cruz Henrik Lundqvist Lily Aldridge Walt Frazier Jake Gyllenhaal Louis C.K. Whoopi Goldberg Lily Aldridge at Cantor’s Charity Day 2016 Cantor Fitzgerald’s Annual Charity Day R Monday, September 11, 2017 at Cantor’s offices, New York City FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Who is Cantor Fitzgerald? Cantor Fitzgerald, a leading global financial services group at the forefront of financial and technological innovation has been a proven and resilient leader for over 65 years. -

Investor Presentation

Disclaimer General This presentation does not constitute an offer or invitation for the sale or purchase of securities and has been prepared solely for informational purposes. The information contained in this presentation (this “Presentation”) has been prepared to assist interested parties in making their own evaluation with respect to the proposed transaction (the “Transaction”) between CF Finance Acquisition Corp. II (“CFII”) and View, Inc. (“View”), and for no other purpose. This Presentation is subject to updating, completion, revision, verification and further amendment. None of CFII, View, or their respective affiliates has authorized anyone to provide interested parties with additional or different information. No securities regulatory authority has expressed an opinion about the securities discussed in this Presentation and it is an offense to claim otherwise. The information contained herein does not purport to be all-inclusive. Nothing herein shall be deemed to constitute investment, legal, tax, financial, accounting or other advice. Confidentiality The purpose of this Presentation is to provide information to assist in obtaining a general understanding of CFII, View and the Transaction. This information is being distributed to you on a confidential basis. By receiving this information, you and your affiliates agree to maintain the confidentiality of the information contained herein and that no portion of this Presentation may either be reproduced in whole or in part and that neither this Presentation nor any of its contents may be given or disclosed to any third party without the express written permission of CFII and View and that the information contained herein is subject to the terms of any confidentiality agreement entered into with CFII and View. -

World Trade Center Dna Identifications: the Administrative Review Process

Draft: WTC DNA Identifications: The Administrative Review WORLD TRADE CENTER DNA IDENTIFICATIONS: THE ADMINISTRATIVE REVIEW PROCESS Mike Hennessey Gene Codes Forensics, Ann Arbor, MI ¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½¾½ Abstract: The Division of Forensic Biology at the Office of Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) in New York City is responsible for the DNA identifications of the victims of the September 11th attack on the World Trade Center (WTC). Both direct references (personal effects) and indirect references (kinship) are used and when a victim sample is linked to a reference set, the victim is identified by reviewing the reference sample’s chain of custody. This has proven to be a serious challenge: in the chaos following the attacks, the collection of reference samples was not always documented completely. In addition, several agencies were engaged in the collection and handling of the samples, resulting in a wide variance of how data was recorded. Finally, the sheer volume of the process (an order of magnitude larger than an airline disaster) presents its own unique challenges. Because its software is already used by the forensic community for mtDNA analysis and the company has worked closely with the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory, Gene Codes Corporation was contacted by the Division of Forensic Biology at the OCME in September of 2001 to help manage the DNA data related to WTC. In response, Gene Codes Forensics, a subsidiary of Gene Codes Corporation, made two distinct deliverables. First, it developed the Mass Fatality Identification System (M-FISys) software to manage the DNA data. Second, it designed a manual Administrative Review Process (“Admin Review”) to establish and verify the chain of custody for the reference samples.