Grade 5: Module 2A: Unit 3: Lesson 6 Conducting Research: Asking and Answering Our Questions About Rainforest Arthropods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developmental, Cellular and Biochemical Basis of Transparency in Clearwing Butterflies Aaron F

© 2021. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2021) 224, jeb237917. doi:10.1242/jeb.237917 RESEARCH ARTICLE Developmental, cellular and biochemical basis of transparency in clearwing butterflies Aaron F. Pomerantz1,2,*, Radwanul H. Siddique3,4, Elizabeth I. Cash5, Yuriko Kishi6,7, Charline Pinna8, Kasia Hammar2, Doris Gomez9, Marianne Elias8 and Nipam H. Patel1,2,6,* ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION The wings of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) are typically covered The wings of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) have inspired with thousands of flat, overlapping scales that endow the wings with studies across a variety of scientific fields, including evolutionary colorful patterns. Yet, numerous species of Lepidoptera have evolved biology, ecology and biophysics (Beldade and Brakefield, 2002; highly transparent wings, which often possess scales of altered Prum et al., 2006; Gilbert and Singer, 1975). Lepidopteran wings morphology and reduced size, and the presence of membrane are generally covered with rows of flat, partially overlapping surface nanostructures that dramatically reduce reflection. Optical scales that endow the wings with colorful patterns. Adult scales are properties and anti-reflective nanostructures have been characterized chitin-covered projections that serve as the unit of color for the wing. for several ‘clearwing’ Lepidoptera, but the developmental processes Each scale can generate color through pigmentation via molecules underlying wing transparency are unknown. Here, we applied that selectively absorb certain wavelengths of light, structural confocal and electron microscopy to create a developmental time coloration, which results from light interacting with the physical series in the glasswing butterfly, Greta oto, comparing transparent nanoarchitecture of the scale; or a combination of both pigmentary and non-transparent wing regions. -

Combining Taxonomic and Functional Approaches to Unravel the Spatial Distribution of an Amazonian Butterfly Community

Environmental Entomology Advance Access published December 7, 2015 Environmental Entomology, 2015, 1–9 doi: 10.1093/ee/nvv183 Community and Ecosystem Ecology Research article Combining Taxonomic and Functional Approaches to Unravel the Spatial Distribution of an Amazonian Butterfly Community Marlon B. Grac¸a,1,2,3 Jose´W. Morais,1 Elizabeth Franklin,1,2 Pedro A. C. L. Pequeno,1,2 Jorge L. P. Souza,1,2 and Anderson Saldanha Bueno,1,4 1Biodiversity Coordination, National Institute for Amazonian Research, INPA, Manaus, Brazil ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]), 2Center for Integrated Studies of Amazonian Biodiversity, CENBAM, Manaus, Brazil, 3Corresponding author, e-mail: marlon_lgp@hotmail. com, and 4Campus Ju´lio de Castilhos, Farroupilha Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology, Brazil ([email protected]) Received 24 August 2015; Accepted 10 November 2015 Abstract This study investigated the spatial distribution of an Amazonian fruit-feeding butterfly assemblage by linking spe- cies taxonomic and functional approaches. We hypothesized that: 1) vegetation richness (i.e., resources) and abun- dance of insectivorous birds (i.e., predators) should drive changes in butterfly taxonomic composition, 2) larval diet breadth should decrease with increase of plant species richness, 3) small-sized adults should be favored by higher abundance of birds, and 4) communities with eyespot markings should be able to exploit areas with higher predation pressure. Fruit-feeding butterflies were sampled with bait traps and insect nets across 25 km2 of an Amazonian ombrophilous forest in Brazil. We measured larval diet breadth, adult body size, and wing marking of all butterflies. -

Amphiesmeno- Ptera: the Caddisflies and Lepidoptera

CY501-C13[548-606].qxd 2/16/05 12:17 AM Page 548 quark11 27B:CY501:Chapters:Chapter-13: 13Amphiesmeno-Amphiesmenoptera: The ptera:Caddisflies The and Lepidoptera With very few exceptions the life histories of the orders Tri- from Old English traveling cadice men, who pinned bits of choptera (caddisflies)Caddisflies and Lepidoptera (moths and butter- cloth to their and coats to advertise their fabrics. A few species flies) are extremely different; the former have aquatic larvae, actually have terrestrial larvae, but even these are relegated to and the latter nearly always have terrestrial, plant-feeding wet leaf litter, so many defining features of the order concern caterpillars. Nonetheless, the close relationship of these two larval adaptations for an almost wholly aquatic lifestyle (Wig- orders hasLepidoptera essentially never been disputed and is supported gins, 1977, 1996). For example, larvae are apneustic (without by strong morphological (Kristensen, 1975, 1991), molecular spiracles) and respire through a thin, permeable cuticle, (Wheeler et al., 2001; Whiting, 2002), and paleontological evi- some of which have filamentous abdominal gills that are sim- dence. Synapomorphies linking these two orders include het- ple or intricately branched (Figure 13.3). Antennae and the erogametic females; a pair of glands on sternite V (found in tentorium of larvae are reduced, though functional signifi- Trichoptera and in basal moths); dense, long setae on the cance of these features is unknown. Larvae do not have pro- wing membrane (which are modified into scales in Lepi- legs on most abdominal segments, save for a pair of anal pro- doptera); forewing with the anal veins looping up to form a legs that have sclerotized hooks for anchoring the larva in its double “Y” configuration; larva with a fused hypopharynx case. -

Revised Species Definitions and Nomenclature of the Rose Colored Cithaerias Butterflies (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Satyrinae)

Zootaxa 3873 (5): 541–559 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3873.5.5 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:05BD334C-493D-4688-92E8-602943ECF57D Revised species definitions and nomenclature of the rose colored Cithaerias butterflies (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae, Satyrinae) CARLA M. PENZ1, LAURA G. ALEXANDER2 & PHILIP J. DEVRIES3 Department of Biological Sciences, University of New Orleans, 2000 Lakeshore Dr. New Orleans, LA 70148, USA. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract This study provides updated species definitions for five rose-colored Cithaerias butterflies, starting with a historical over- view of their taxonomy. Given their mostly transparent wings, genitalia morphology yielded the most reliable characters for species definition and identification. Genitalic divergence is more pronounced when multiple species occur in sympa- try than between parapatric taxa. Cithaerias aurorina is granted full species status, C. cliftoni is reinstated as a full species, and one new combination is proposed, i.e. C. aurora tambopata. Two new synonyms are proposed, Callitaera phantoma and Callitaera aura = Cithaerias aurora. Key words: pireta, menander, aurorina, cliftoni, aurora, aura, phantoma, pyritosa Introduction Some of the most visually striking Neotropical butterflies belong to the genus Cithaerias Hübner (Satyrinae, Haeterini), which inhabit sea level to mid-elevation rainforests from Mexico through Central and South America. A characteristic of all Cithaerias species is their mostly transparent wings with the distal portions of the hind wing overlaid with partially lustrous rose, purple or blue scales. -

Science Manuscript Template

Developmental, cellular, and biochemical basis of transparency in clearwing butterflies Aaron F. Pomerantz1,2,*, Radwanul H. Siddique3,4, Elizabeth I. Cash5, Yuriko Kishi6,7, Charline Pinna8, Kasia Hammar2, Doris Gomez9, Marianne Elias8, Nipam H. Patel1,2,6,* 1Department Integrative Biology, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720. 2Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543. 3Image Sensor Lab, Samsung Semiconductor, Inc., 2 N Lake Ave. Ste. 240, Pasadena, CA 91101. 4Department of Medical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125. 5Department of Environmental Science, Policy, & Management, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720. 6Department Molecular Cell Biology, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720. 7Department of Biology and Biological Engineering, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125. 8ISYEB, 45 rue Buffon, CP50, Paris, CNRS, MNHN, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, Université des Antilles, France. 9CEFE, 1919 route de Mende, Montpellier, CNRS, Univ Montpellier, Univ Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, EPHE, IRD, France. * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Summary Statement: Transparency is a fascinating, yet poorly studied, optical property in living organisms. Here, we elucidate the developmental processes underlying scale and nanostructure formation in glasswing butterflies, and their roles in generating anti-reflective properties. © 2021. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd. Journal of Experimental Biology • Accepted manuscript This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided that the original work is properly attributed Abstract The wings of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) are typically covered with thousands of flat, overlapping scales that endow the wings with colorful patterns. -

Taxonomic Revision of the “Pierella Lamia Species Group” (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Satyrinae) with Descriptions of Four New Species from Brazil

Zootaxa 4078 (1): 366–386 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4078.1.31 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:203F313A-5A03-4514-A5F3-BB315A6B7FF6 Taxonomic revision of the “Pierella lamia species group” (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Satyrinae) with descriptions of four new species from Brazil THAMARA ZACCA1,3, RICARDO R. SIEWERT1, MIRNA M. CASAGRANDE1, OLAF H. H. MIELKE1 & MÁRLON PALUCH2 1Departamento de Zoologia, Laboratório de Estudos de Lepidoptera Neotropical, Universidade Federal do Paraná - UFPR, Caixa Postal 19020, 81531–980, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil. 2Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia, Centro de Ciências Agrárias Ambientais e Biológicas, Setor de Biologia, 44380–000, Cruz das Almas, Bahia, Brazil. 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Four new species of Pierella Westwood, 1851 from Brazil are described: P. angeloi Zacca, Siewert & Mielke sp. nov. from Maranhão, P. kesselringi Zacca, Siewert & Paluch sp. nov. from Paraíba, Pernambuco, Alagoas and Sergipe, P. nice Zacca, Siewert & Paluch sp. nov. from Bahia and P. keithbrowni Siewert, Zacca & Casagrande sp. nov. from Bahia, Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Paraná and Santa Catarina. Additionally, P. chalybaea Godman, 1905 stat. rest. and P. bo- liviana F.M. Brown, 1948 stat. nov. are recognized as valid species and not as subspecies of P. l am i a (Sulzer, 1776), while P. l. colombiana Constantino & Salazar, 2007 syn. nov. is synonymized to the former. Lectotype and paralectotype of Pap- ilio dyndimene Cramer, 1779 (a synonym of Pierella lamia) and Pierella chalybaea Godman, 1905 stat. -

Morphological and Molecular Evidence Supports Recognition Of

Morphological and molecular evidence supports recognition of Cithaerias cliftoni (Constantino, 1995) as a species distinct from C. pireta (Stoll, 1780) and C. aurorina (Weymer, 1910) Luis Miguel Constantino 2016 Supplementary Material: Constantino, 2016. Revision of the tribe Haeterini (Lepidoptera: Satyirnae) Remarks on the nominal taxon Cithaerias cliftoni (Constantino, 1995) Cithaerias cliftoni Constantino, 1995 is a member of the tribe Haeterini (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Satyrinae) confined to the Neotropical region. The butterflies of this tribe, are for the most part, readily distinguished from all other groups of the Satyrinae by having largely transparent wings with one or two ocelli and patches of color on the hindwing margin (Constantino 1992). C. cliftoni is a good species inhabiting the rainforests of the upper Amazon basin in the eastern slopes of the Andes of Colombia, Ecuador and North of Peru, not sympatric with C. aurora (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1862) (Penz et. al. 2014). C. cliftoni was synonymized by Lamas (2004) with C. phantoma (Fassl, 1922) from Manicoré at Rio Madeira, Tefé and São Paulo de Olivença, Amazonas, Brazil, a very distant population from Colombia, however Lamas (1998) was not able to locate the type material of C. phantoma. As a result of this Penz et. al (2014) synonymized C. phantoma with C. aurora and reinstated C. cliftoni as a full species based on morphological differences of the genitalia. Geographical distribution C. cliftoni is found in the east slope of the Andes of Colombia, Ecuador and North of Perú. In Colombia is found in the departments of Meta, Caquetá and Putumayo at an altitudinal range of 100 up to 800 m. -

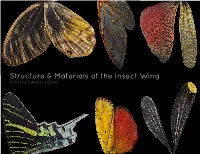

Structure & Materials of the Insect Wing

Structure & Materials of the Insect Wing Article by Samantha Chalut Background To this day, Evolution the true origins of insect flight remains obscure, as the earliest he earliest insects had four winged insects show evidence of Twings, independently being fully adept at flight. functioning forewings and hindwings. The well-known insects, n insect’s wings are outgrowths damselflies and dragonflies, have Aof the exoskeleton that enable kept this design. Since then, insect it to fly; this includes two pairs of wing designs vary where either the wings known as the forewing and forewing or hindwing are hindwing (although a select few specialized for force production, insects lack hindwings). The while many other insects are current designs of an insect wings functionally 2 winged through have evolved over hundreds of attaching the smaller hindwings millions of years to produce many to the forewings. variations, each with it’s own design tradeoffs. These tradeoffs may include specializations in the flight performance aspects such as efficiency, versatility, maneuverability, or stability. Structure he structure and design of an insect Twing is essential, as it must endure functionally over the insect’s lifespan. They must be capable of enduring collisions or tearing without failure. To achieve this insect wings can deform readily, even reversibly, through its overall structure. In many cases aerodynamic efficiency is improved through the coupling of the forewing and hindwing. This is achieved in a few different ways. Most commonly, the wings are coupled through a row of small hooks on the forward margin of the hindwing, locking onto the forewing. Another form of coupling is seen where Grasshopper forewing vein celled intersections the jugal lobe of the forewing covers a portion of the hindwing, or even where they broadly overlap. -

453Cd58776f197dffcca60d1fa3a

Editora Chefe Profª Drª Antonella Carvalho de Oliveira Assistentes Editoriais Natalia Oliveira Bruno Oliveira Flávia Roberta Barão Bibliotecário Maurício Amormino Júnior Projeto Gráfico e Diagramação Natália Sandrini de Azevedo Camila Alves de Cremo Karine de Lima Wisniewski Luiza Alves Batista Maria Alice Pinheiro Imagens da Capa 2020 by Atena Editora Shutterstock Copyright © Atena Editora Edição de Arte Copyright do Texto © 2020 Os autores Luiza Alves Batista Copyright da Edição © 2020 Atena Editora Revisão Direitos para esta edição cedidos à Atena Editora Os Autores pelos autores. Todo o conteúdo deste livro está licenciado sob uma Licença de Atribuição Creative Commons. Atribuição 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0). O conteúdo dos artigos e seus dados em sua forma, correção e confiabilidade são de responsabilidade exclusiva dos autores, inclusive não representam necessariamente a posição oficial da Atena Editora. Permitido o download da obra e o compartilhamento desde que sejam atribuídos créditos aos autores, mas sem a possibilidade de alterá-la de nenhuma forma ou utilizá-la para fins comerciais. A Atena Editora não se responsabiliza por eventuais mudanças ocorridas nos endereços convencionais ou eletrônicos citados nesta obra. Todos os manuscritos foram previamente submetidos à avaliação cega pelos pares, membros do Conselho Editorial desta Editora, tendo sido aprovados para a publicação. Conselho Editorial Ciências Humanas e Sociais Aplicadas Prof. Dr. Álvaro Augusto de Borba Barreto – Universidade Federal de Pelotas Prof. Dr. Alexandre Jose Schumacher – Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de Mato Grosso Prof. Dr. Américo Junior Nunes da Silva – Universidade do Estado da Bahia Prof. Dr. Antonio Carlos Frasson – Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná Prof. -

Lepidoptera Diversity of an Ecuadorian Lowland Rain Forest1

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Neue Entomologische Nachrichten Jahr/Year: 1998 Band/Volume: 41 Autor(en)/Author(s): Racheli Tommaso, Racheli Luigi Artikel/Article: Lepidoptera diversity of an Ecuadorian lowland rain forest (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae, Pieridae, Nymphalidae, Saturniidae, Sphingidae) 95- 117 -9 5 - Lepidoptera diversity of an Ecuadorian lowland rain forest1 (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae, Pieridae, Nymphalidae, Saturniidae, Sphingidae) by Tommaso Racheli & L uigi Racheli Introduction Faunistic lists are a very important tool for several fields in biological researches. We must stress however that comparisons of faunistic lists of different sites are always difficult to be made due to differences in area size, to divergence in classification, and to the differences of the operators techniques. Therefore it is often uneasy to deal with sets of data and to compare the results. None the less, surveys and comparisons of butterflies in selected sites of the Neotropical realm seem to be very popular nowadays (Lamas , 1983a, 1983b; Lamas et al., 1991; Raguso & Llorente , 1991; Austin et al., 1996; Balcazar , 1993). They are particularly aimed at gathering sets of data tor conservation purposes and at identifying hotspots of endemicity. Dramatic is the lacking of published long-term surveys on moths in limited areas of the Neotropics. Unexpectedly, no recent faunistic lists of Ecuadorian butterflies have appeared except that of Ma- quipucuna Reserve on the western side of the country (Raguso & G loster , 1996). Having observed butterflies, Saturniids and Hawkmoths for almost 15 years in Ecuador, as Clench (1979) suggests, the time is arrived to submit a survey of these taxa occuring in an Amazonian area of Ecuador. -

Comparative Biology of Three Species of Costa Rican Haeterini

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-16-2014 Comparative Biology of Three Species of Costa Rican Haeterini Laura Alexander University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Alexander, Laura, "Comparative Biology of Three Species of Costa Rican Haeterini" (2014). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1843. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1843 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparative Biology of Three Species of Costa Rican Haeterini A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Conservation Biology By Laura G. Alexander B.A. Stetson University, 1987 May 2014 Copyright 2014, Laura G. Alexander ii Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge Ann Cespedes, Isidro Chacón, Chevo Cascante, Anne Johnston Davis, Katherine Díaz, Jessica Edwards, Alex Figueroa, Cristian Miranda, Sergio Padilla, Emmanuel Rojas, and Danielle Salisbury for field assistance, and the staff of the Tirimbina Biological Reserve for logistical assistance and research facilities. -

Systematics of Neotropical Satyrine Butterflies

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 Systematics of Neotropical Satyrine Butterflies (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae: Euptychiina) Based on Larval Morphology and DNA Sequence Data and the Evolution of Life History Traits. Debra Lynne Murray Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Murray, Debra Lynne, "Systematics of Neotropical Satyrine Butterflies (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae: Euptychiina) Based on Larval Morphology and DNA Sequence Data and the Evolution of Life History Traits." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 424. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/424 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.