Submission 49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIGHTING WORKSHOP 2018 2018 Brisbane Airportconference Centre Tuesday 22May Brisbane Airportconference Centre Tuesday 22May

LIGHTING WORKSHOP Tuesday 22 May 2018 Brisbane Airport Conference Centre PAVEMENT TECHNOLOGY WORKSHOP Tuesday 22 May 2018 Brisbane Airport Conference Centre PROGRAM www.airports.asn.au THE AUSTRALIAN AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION The AAA facilitates co-operation among all member airports and their many and varied partners in Australian aviation, whilst The Australian Airports Association (AAA) The AAA represents the interests of over contributing to an air transport system that is a non-profit organisation that was 380 members. This includes more than is safe, secure, environmentally responsible 260 airports and aerodromes Australia and efficient for the benefit of all Australians founded in 1982 in recognition of the real wide – from the local country community and visitors. need for one coherent, cohesive, consistent landing strip to major international and vital voice for aerodromes and airports gateway airports. The AAA is the leading advocate for throughout Australia. appropriate national policy relating to The AAA also represents more than airport activities and operates to ensure 120 aviation stakeholders and regular transport passengers, freight, and organisations that provide goods and the community enjoy the full benefits of a services to airports. progressive and sustainable airport industry. CONTACT US P: 02 6230 1110 E: [email protected] w: www.airports.asn.au Welcome to the AAA Pavement Technology Workshop and Lighting Workshop. These are two new events for 2018, and form part of the commitment the AAA has to provide the aviation industry with comprehensive technical training and research updates. We know how important it is to meet your peers and share ideas at these occasions, so we hope you enjoy the opportunity to attend our Networking Drinks, overlooking Brisbane Airport runway, at the Sky Lounge, IBIS. -

Australian Diurnal Raptors and Airports

Australian diurnal raptors and airports Photo: John Barkla, BirdLife Australia William Steele Australasian Raptor Association BirdLife Australia Australian Aviation Wildlife Hazard Group Forum Brisbane, 25 July 2013 So what is a raptor? Small to very large birds of prey. Diurnal, predatory or scavenging birds. Sharp, hooked bills and large powerful feet with talons. Order Falconiformes: 27 species on Australian list. Family Falconidae – falcons/ kestrels Family Accipitridae – eagles, hawks, kites, osprey Falcons and kestrels Brown Falcon Black Falcon Grey Falcon Nankeen Kestrel Australian Hobby Peregrine Falcon Falcons and Kestrels – conservation status Common Name EPBC Qld WA SA FFG Vic NSW Tas NT Nankeen Kestrel Brown Falcon Australian Hobby Grey Falcon NT RA Listed CR VUL VUL Black Falcon EN Peregrine Falcon RA Hawks and eagles ‐ Osprey Osprey Hawks and eagles – Endemic hawks Red Goshawk female Hawks and eagles – Sparrowhawks/ goshawks Brown Goshawk Photo: Rik Brown Hawks and eagles – Elanus kites Black‐shouldered Kite Letter‐winged Kite ~ 300 g Hover hunters Rodent specialists LWK can be crepuscular Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Photo: Herald Sun. Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Large ‐ • Wedge‐tailed Eagle (~ 4 kg) • Little Eagle (< 1 kg) • White‐bellied Sea‐Eagle (< 4 kg) • Gurney’s Eagle Scavengers of carrion, in addition to hunters Fortunately, mostly solitary although some multiple strikes on aircraft Hawks and eagles –large kites Black Kite Whistling Kite Brahminy Kite Frequently scavenge Large at ~ 600 to 800 g BK and WK flock and so high risk to aircraft Photo: Jill Holdsworth Identification Beruldsen, G (1995) Raptor Identification. Privately published by author, Kenmore Hills, Queensland, pp. 18‐19, 26‐27, 36‐37. -

Aerospace Action Plan Progress Report

QUEENSLAND AEROSPACE 10-Year Roadmap and Action Plan PROGRESS REPORT By 2028, the Queensland aerospace industry will be recognised as a leading centre in Australasia and South East Asia for aerospace innovation in training; niche manufacturing; maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO); and unmanned aerial systems (UAS) applications for military and civil markets. Launch Completion 2018 2028 International border closures due to COVID-19 had a dramatic impact on the aerospace industry in Queensland, particularly the aviation sector. Despite this temporary industry downturn, the Queensland Government has continued to stimulate the aerospace industry through investment in infrastructure, technology and international promotion. I look forward to continuing to champion Queensland aerospace businesses, taking the industry to new heights. The Honourable Steven Miles MP DEPUTY PREMIER and MINISTER FOR STATE DEVELOPMENT Case study – Queensland Flight Test Range in Cloncurry The Queensland Government has invested $14.5 million to establish the foundation phase of a common-user flight test range with beyond visual line of sight capabilities at Cloncurry Airport. The Queensland Flight Test Range (QFTR) provides a critical missing element in the UAS ecosystem for industry and researchers to test and develop complex technologies. Operated by global defence technology company QinetiQ, the QFTR supports the Queensland Government’s goal of establishing the state as a UAS centre of excellence and a UAS leader in the Asia-Pacific region. Inaugural testing at QFTR was completed by Boeing Australia in late 2020. Director of Boeing Phantom Works International Emily Hughes said the company was proud to be the first user of the site and would take the opportunity to continue flight trials on key autonomous projects. -

Download Itinerary

14 Day Cape York, Reef & Outback Cairns Bamaga,QLD Daintree National Park Cape Tribulation,QLD Cooktown Great Barrier Reef,QLD Port Douglas Mount Isa Longreach,QLD Winton,QLD Let Us Inspire You FROM $6,999 PER PERSON, TWIN SHARE Book Now TOUR ITINERARY The information provided in this document is subject to change and may be affected by unforeseen events outside the control of Inspiring Vacations. Where changes to your itinerary or bookings occur, appropriate advice or instructions will be sent to your email address. Call 1300 88 66 88 Email [email protected] www.inspiringvacations.com Page 1 TOUR ITINERARY DAY 1 Destination Cairns Meals included Hotel 4 Park Regis City Quays, or similar Welcome to Cairns! On arrival, make your way to your hotel. The rest of your day is free to explore Cairns at your own pace. Check in & arrival information A taxi or Uber from Cairns airport to your accommodation costs approximately $15 per car. Hotel check in is at 2pm. Should you arrive earlier than this, hotel staff will do all possible to check you in as soon as possible. If your room is not available before check-in time, you are welcome to leave your luggage in storage and explore the surrounding area. DAY 2 Cairns Bamaga Tip of Australia Bamaga Destination Cairns Meals included Breakfast, Lunch Hotel 4 Park Regis City Quays, or similar Gear up for a spectacular day as you travel by air and 4WD to the northernmost point of Australia. At the appropriate time, make your way to Cairns airport to meet your pilot and guide for the day. -

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE 24 December 2008 QUEENSLAND AIRPORTS LIMITED WELCOMES ANNOUNCEMENT ON CAIRNS AIRPORT Queensland Airports Limited (QAL) today welcomes the news of the sale of Cairns Airport to a purchasing consortium including JP Morgan, The Infrastructure Fund (TIF) and the Westpac Banking Corporation. QAL has been appointed to provide expert technical services to the consortium. QAL Managing Director Dennis Chant said Cairns Airport was a significant opportunity for the growth of the Group. “QAL has unique experience in managing regional airports in Queensland and we welcome the announcement today that our shareholders in partnership with JP Morgan have secured this vital piece of infrastructure. “Cairns is a world renowned tourism destination and we are very keen to connect with local industry stakeholders to maintain Cairns International Airport’s pivotal role in facilitating visitation to Tropical North Queensland. “As the owner operator of Gold Coast Airport, QAL management is well versed in the need to develop cooperative marketing alliances with state and local tourism industry stakeholders to attract visitors in a fiercely competitive leisure market,” he said. “Working together, Cairns, Gold Coast and Queensland Tourism will present a formidable competitor to the newly emerging Asian destinations that have been successfully making inroads into our traditional source markets. “QAL also owns and operates Townsville and Mount Isa Airports, and provides technical services expertise to Mackay Airport, all of which have a strong business and resource sector. We look forward to working with the local Cairns business sector to ensure the Far North Queensland region continues to grow. …/2 “QAL is already a significant employer in regional Queensland. -

Cairns Airport Drives Revenue with Ideas Car Park Product and Price Optimization Services

Press Contact: Haberman for IDeaS Megan Mell, PR Representative [email protected] +1 612 436 5549 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Cairns Airport Drives Revenue with IDeaS Car Park Product and Price Optimization Services North Queensland airport partners with global revenue management leader to maximize non-aeronautical revenue CAIRNS, AUSTRALIA – NOVEMBER 23, 2015 – IDeaS Revenue Solutions, the leading provider of revenue management software solutions and advisory services, today announced that Cairns Airport is accessing their Car Park Product and Price Optimization Services (PPOS) to identify new opportunities to optimize its car parking business. Cairns Airport is part of NQA (the North Queensland Airports group), a consortium that also owns Mackay Airport. As the seventh busiest airport in Australia, Cairns sees almost five million passengers annually pass through its two terminals providing daily service to an expanding range of domestic and international destinations. More than 1,600 car spaces are available for short and long-term parking for passengers and visitors. “We’re experiencing significant growth in passenger numbers and this is set to continue with our increase in direct flights to Asia,” said Fiona Ward, General Manager Commercial for NQA. “Demand for parking is strong, and we are excited to work with IDeaS and ensure we’re doing everything we can to offer our customers a range of parking products at the right price, and find new opportunities to optimize use of our car parks.” IDeaS Car Park Product and Price Optimization Services (PPOS) are part of the comprehensive revenue management solution IDeaS offers worldwide for airport car parks. Suitable for any airport with reserved parking, IDeaS Car Park PPOS starts with historical parking data from across the business and analyses it with advanced tools from SAS®, the leader in business analytics and the largest independent vendor in the business intelligence market. -

Mackay Airport Aerodrome Manual

MACKAY AIRPORT AERODROME MANUAL Reference No: 9000MKY Version 11 26 Feb 2021 ACN 132 228 534 AERODROME MANUAL PART 0 SECTION 01 FOREWORD Mackay Airport Pty Ltd owns and manages Mackay Airport which includes all airside and landside operations, terminals, car parking and associated land holdings and is part of the North Queensland Airports (NQA) group. NQA is owned by a consortium comprising of IIF Cairns Mackay Investment Ltd (an entity advised by JP Morgan Asset Management), The Infrastructure Fund (TIF) and Perron Investments. For quality control purposes, this document is only valid on the day it is printed. Official versions are stored on the intranet. This copy was last saved: 01/03/2021 , last printed: 02/03/2021 9000_MKY_Aerodrome Manual_Effective Date: 26/02/2021 Review Date: 25/02/2022 Page 2 of 102 AERODROME MANUAL The Aerodrome Manual contains details of the airside operating procedures that we importantly need to adopt to ensure the safety and viability of our airport. The Aerodrome Manual also satisfies our legal obligations under the Civil Aviation Safety Regulations (CASR) Part 139, in particular CASR 139.090. Any items under CASR 139.0959(a) that are not applicable to Mackay Airport, are not included within this manual. Mackay Airport is transitioning to its Aerodrome Manual line with Part 139 (Aerodromes) Manual of Standards 2019. Mackay Airport has received written approval from CASA for the Aerodrome Manual to consist of more than one document. All separate documents referenced throughout this manual are readily available from Mackay Airport and each staff member is responsible for ensuring that they can access these documents. -

Queensland Outback to Reef 2022 BROCHURE.Pub

EXPLORE LONGREACH, WINTON, MOUNT ISA, CLONCURRY, KARUMBA, COBBOLD GORGE, UNDARA, CAIRNS AND MORE 15 - 28 May 2022 14 Days for $5,990 PRICE IS PER PERSON TWIN SHARE. SINGLE SUPPLEMENT EXTRA $1,360 CONTACT KTG TOURS TO BOOK YOUR SEAT [email protected] | 02 9007 2443 | www.ktgtours.com.au EXPLORE LONGREACH, WINTON, MOUNT ISA, CLONCURRY, KARUMBA, COBBOLD GORGE, UNDARA, CAIRNS AND MORE ON KTG TOURS 14 DAY QUEENSLAND OUTBACK TO REEF TOUR Please note that for full enjoyment of this tour, a reasonable level of fitness is required. Day 1 Sunday 15 May 2022 Meals: D Your tour starts at Sydney Airport where you meet your KTG Tours Hostess who will accompany you on your 14 day adventure. Our Qantas flight departs Sydney at around 11am, with a short stopover in Brisbane before arriving in Longreach mid afternoon.* On arrival at Longreach Airport, we are met by our Driver who will transfer us to our accommodation where we spend the next 2 nights. Get to know your fellow travellers over a tasty meal tonight in town. Hotel: Outback Pioneers, LONGREACH Day 2 Monday 16 May 2022 Meals: B, L, D This morning we visit the impressive Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame. Explore the Galleries with your virtual guide “Hugh”, take your seat in the undercover stadium for the Live Show - A Stockman’s Life and see the Story of the Australian Stockman in a fully immersive cinema experience. Next, we visit the Qantas Founders Museum where we have lunch followed by some time to explore the Museum at your own pace. -

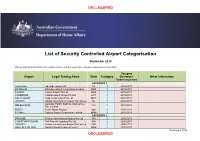

Airport Categorisation List

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty. -

MINUTES AAA QLD Division

MINUTES AAA QLD Division Wednesday 21 March 2018 Brisbane Airport Conference Centre, Brisbane Chair: Rob Porter – General Manager Mackay Airport Attendees: List of Attendees Attached Apologies: Rob MacTaggart (The Airport Group) 1. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES FROM PREVIOUS MEETING: Noted minutes from last meeting. 2. WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONS: Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) opened the meeting, welcomed members and thanked Smiths Detection for sponsoring the meeting. Also thanked our division dinner sponsors Trident Services and Airport Equipment. Noted the excellent presentation from Neil Scales at the dinner, noting that we will invite him back in 12 months’ time to share his experiences. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) encouraged members to provide feedback to the AAA team on the recent communications innovations (airport professional, the centre line, social media, etc.) The hot topics section at the end of the agenda was noted and the Chair, encouraged members to share their thoughts. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) encouraged members to provide feedback on the number and structure of division meetings. Noted ‘out of the box’ topic suggestions are always welcome. Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) provided members with an overview of the agenda. Noting the ‘around the tarmacs’ section and encouraged members share their activity. QLD Overview Rob Porter (General Manager Mackay Airport) noted increase pressure across the state in access to aircraft, this has put upwards pressure on regional airfares in particular. 1 3. AAA UPDATE Simon Bourke (Policy Director AAA) noted key topics that the AAA had been working on over the past 6 months. Security Changes Proposed changes to Aviation Security will have an impact on all aviation sectors. -

North Queensland Airports (NQA)

Invest & Manage Airports 2011 London December 9th, 2011 North Queensland Airports (NQA) In January 2009, a consortium led by institutional investors advised by J.P.Morgan Asset Management bought Cairns & Mackay airports from the Queensland government NQA owns and manages Cairns and Mackay airports under 99-year leases – Cairns is Australia's 7th largest airports with c. 4.0m pax in FY11 and the gateway to World Heritage Great Barrier Reef and Tropical Rainforests of Northern Queensland – Mackay airport, with c. 1m pax in FY11, is the main airport serving the Bowen Basin, which contains one of the largest deposits of coal in the world 2 NQA - Overview Cairns Airport Cairns Airport 758 ha site located c.8 km from the CBD Separate domestic & international terminals Two runways: main runway (3,197m) & cross runway (925m) Curfew free Mackay Airport Mackay Airport 274 ha site located c.5 km from the CBD Single terminal Two runways: main runway (1,981m), cross runway (1,344m) Curfew free 3 NQA – Passenger Profile Cairns Mackay 6% 6% 12% 25% 44% 11% 64% NQA 25% 6% 16% 17% 61% Leisure Business VFR Other 4 NQA – Strong Traffic performance since Acquisition FY 2011/2010 Passenger growth 9.9% 9.5% 7.7% 6.9% 4.3% 4.1% 3.6% NQA Perth Airport APAC MAp QAL Sydney Airport NT Airports 5 Continued route expansion and carrier diversification 81 new services and new routes introduced since acquisition equating to over 1.4m new seats Both Cairns and Mackay have experienced strong volumes growth as a result of: – Strategically marketing the airport -

Climate Risk Assessment for North Queensland Airports

Snapshot Climate risk assessment for North Queensland Airports North Queensland Airports (NQA) operates the Cairns and Mackay Airports on leased state land. Summary Cairns Airport (shown in Figure 1) is one of the largest airports in Northern Australia and an international North Queensland Airports (NQA) operates gateway to the Great Barrier Reef and World Heritage the Cairns and Mackay Airports, which are listed rainforests. Mackay Airport (shown in Figure 2) situated on the tropical North Queensland is a key piece of transport infrastructure for the region, coast. Cyclonic activity, flooding and storm servicing residents including fly-in fly-out mining surge can damage airport infrastructure workers, and supporting the local economy. as well as impact operations. Under future climate change and associated sea-level The airports are situated on the tropical North rise, these impacts are likely to intensify. Queensland coast. Both have been built on low To better understand climate risks to the elevation coastal land (reclaimed mangrove airports both now and in the future, NQA ecosystems), are situated in cyclonic regions, undertook an internal risk screening and risk experience high temperatures during summer and assessment process using the mapping tools have climate-sensitive assets and operations. and guidelines published in CoastAdapt. The In particular, intense cyclones and associated storm risk assessment looked comprehensively at surges and flooding can damage airport infrastructure current risks as well as future risks in 2030 and as well as impact operations by causing temporary 2070, producing a risk register that will inform closures. Under future climate change and sea-level long term planning.