The Influence of Marketing Mix Variables on Taekwondo Participants' Satisfaction and Post-Purchase Behavior Sangwon Na, Jeffrey D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olympic Charter

OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 © International Olympic Committee Château de Vidy – C.P. 356 – CH-1007 Lausanne/Switzerland Tel. + 41 21 621 61 11 – Fax + 41 21 621 62 16 www.olympic.org Published by the International Olympic Committee – July 2020 All rights reserved. Printing by DidWeDo S.à.r.l., Lausanne, Switzerland Printed in Switzerland Table of Contents Abbreviations used within the Olympic Movement ...................................................................8 Introduction to the Olympic Charter............................................................................................9 Preamble ......................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Principles of Olympism .......................................................................................11 Chapter 1 The Olympic Movement ............................................................................................. 15 1 Composition and general organisation of the Olympic Movement . 15 2 Mission and role of the IOC* ............................................................................................ 16 Bye-law to Rule 2 . 18 3 Recognition by the IOC .................................................................................................... 18 4 Olympic Congress* ........................................................................................................... 19 Bye-law to Rule 4 -

Point-Of-Care Ultrasound for Injured Athletes in the Taekwondo Competition

Point-of-Care Ultrasound for injured athletes in the Taekwondo Competition Dae Hyoun Jeong, MD IOC Dip Sp Phy, CAQSM, CAQGM, RMSK, RDMS, CEP, CET Assistant Professor Director, Sports Medicine and Geriatric MSK Medicine Director, Point-of-Care Ultrasound Program Department of Family and Community Medicine Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Springfield, Illinois, USA DISCLOSURE I, Dae Hyoun Jeong, MD, or family member(s), have no relevant financial relationships to be disclosed, directly or indirectly, referred to or illustrated with or without recognition within the presentation. WTF Commission Doctor, 2017 Muju WTF World Taekwondo Championship . Venue Physician - 2017 IIHF Woman’s Ice Hocky World Championship . Venue Medical Officer - Bobsleigh, 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics . Medical Director - Illinois Taekwondo State Organization (ITSO), USA . Medical Director - Missouri State Taekwondo Organization (MSTO), USA . Medical Director, Advisory Board, Illinois Senior Olympics, Illinois, USA . Captain, 5th Medical Tent - 2017 Chicago International Marathon Game . Ringside physician for MMA(mixed martial arts) games . Team Physician for American football teams (high school and collegiate level) OBJECTIVES • Review the epidemiology of injuries in Taekwondo athletes during the competition • Explain the pros and cons of point-of-care ultrasound (musculoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal) as a diagnostic modality • Describe the ultrasound characteristics of fractures, dislocations and soft tissue injuries • Explain the applications -

Sportonsocial 2018 1 INTRODUCTION

#SportOnSocial 2018 1 INTRODUCTION 2 RANKINGS TABLE 3 HEADLINES 4 CHANNEL SUMMARIES A) FACEBOOK CONTENTS B) INSTAGRAM C) TWITTER D) YOUTUBE 5 METHODOLOGY 6 ABOUT REDTORCH INTRODUCTION #SportOnSocial INTRODUCTION Welcome to the second edition of #SportOnSocial. This annual report by REDTORCH analyses the presence and performance of 35 IOC- recognised International Sport Federations (IFs) on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube. The report includes links to examples of high-performing content that can be viewed by clicking on words in red. Which sports were the highest climbers in our Rankings Table? How did IFs perform at INTRODUCTION PyeongChang 2018? What was the impact of their own World Championships? Who was crowned this year’s best on social? We hope you find the report interesting and informative! The REDTORCH team. 4 RANKINGS TABLE SOCIAL MEDIA RANKINGS TABLE #SportOnSocial Overall International Channel Rank Overall International Channel Rank Rank* Federation Rank* Federation 1 +1 WR: World Rugby 1 5 7 1 19 +1 IWF: International Weightlifting Federation 13 24 27 13 2 +8 ITTF: International Table Tennis Federation 2 4 10 2 20 -1 FIE: International Fencing Federation 22 14 22 22 3 – 0 FIBA: International Basketball Federation 5 1 2 18 21 -6 IBU: International Biathlon Union 23 11 33 17 4 +7 UWW: United World Wrestling 3 2 11 9 22 +10 WCF: World Curling Federation 16 25 12 25 5 +3 FIVB: International Volleyball Federation 7 8 6 10 23 – 0 IBSF: International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation 17 15 19 30 6 +3 IAAF: International -

London 2017 World Taekwondo Grand-Prix & World Para-Taekwondo Championships

GSI Event Study London 2017 World Taekwondo Grand-Prix & World Para-Taekwondo Championships London, United Kingdom 19 – 22 October 2017 GSI EVENT STUDY / LONDON 2017 WORLD TAEKWONDO GRAND-PRIX & WORLD PARA-TAEKWONDO CHAMPIONSHIPS GSI Event Study London 2017 World Taekwondo Grand-Prix & World Para-Taekwondo Championships This Event Study is subject to copyright agreements. No part of this Event Study PUBLISHED MAY 2018 may be reproduced distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means BY SPORTCAL GLOBAL or stored in any retrieval system of any nature without prior written permission. COMMUNICATIONS LTD Application for permission for use of copyright material shall be made to Sportcal Global Communications Ltd (“Sportcal”). Sportcal has prepared this Event Study using reasonable skill, care and diligence Authors for the sole and confidential use of World Taekwondo (“WT”) and GB Taekwondo for the purposes set out in the Event Study. Sportcal does not Beth McGuire assume or accept or owe any responsibility or duty of care to any other person. Tim Rollason Any use that a third party makes of this Event Study or reliance thereon or any decision made based on it, is the responsibility of such third party. Research and editorial support The Event Study reflects Sportcal’s best judgement in the light of the information available at the time of its preparation. Sportcal has relied upon the Edward Frain completeness, accuracy and fair presentation of all the information, data, advice, Matt Finch opinion or representations (the “Information”) obtained from public sources and Andrew Horsewood from WT, GB Taekwondo, UK Sport and various third-party providers. -

Athlete Classification Rules As of January 1, 2017

Athlete Classification Rules as of January 1, 2017 Purpose and Organization of these Rules Purpose These Athlete Classification Rules (referred to generally as “the Rules”) provide a framework within which the process of “Classification” may take place. The term “Classification” refers to a structure for Competition the aim of which is to ensure that an Athlete’s Impairment is relevant to sport performance, and to ensure that Athletes compete equitably with each other. The purpose of Classification is to minimise the impact of eligible Impairment types on the outcome of competition, so that Athletes who succeed in competition are those with best anthropometry, physiology and psychology and who have enhanced them to best effect. Organisation Articles Article One Article One explains that these Rules apply to persons who compete or are otherwise involved in the sport of Taekwondo, and how the Rules should be interpreted. Article Two Article Two explains that qualified personnel referred to in these Rules as “Classifiers” conduct Athlete Evaluation, with other key “Classification Personnel” being involved. Article Three Article Three explains how Classifiers will conduct Athlete Evaluation as part of a Classification Panel. Article Four Article Four explains that the process of Classification is carried out by way of Athlete Evaluation under these Rules, and details the specific processes and protocols to be followed during Athlete Evaluation. Article Five Article Five explains that Classification is undertaken so that Athletes can be designated a Sport Class (which groups Athletes together in Competition) and allocated a Sport Class Status (which indicates when Athletes should be evaluated and how their Sport Class may be challenged). -

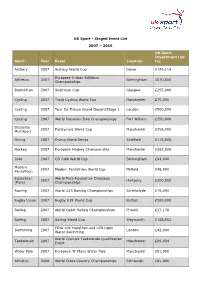

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

Reporter Stirling Vincent 07112019

Thursday, November 7, 2019 COMMUNITYNEWS.COM.AU ReEASTEpoRN rter VINCENT &STIRLING In aspinover INSIDE anniversary RTRFM’s reggae show Jamdown Ver- shun will celebrate40years on the air this month. It plans aliveshow to mark the occasion. See page 5. WA SENIORS WEEK SPECIAL General Justice and Mumma Trees FEATURE from JamdownVershun. Picture: Andrew Ritchie www.communitypix.com.au d496233 CELEBRATING OUR SENIORS ARTSURGERY Pages 18-22 Michael Palmer thepolicyexpanded to in- include ground floor tenan- add to the public amenity of on how to improve opportu- clude performing and cre- cies theoretically intended an area. nities for creative spaces in PERFORMING arts and art ative arts. to activate streets but the “A broadening of the the city,” Mr Hammond studios could be used to fill Arecent survey of 30 amount of floor space is fast Percent for Art categories said. vacant retail spaces under WA councils found four in exceeding demand, leading would allow for the cre- The City’s cultural de- aplan presented to WA five (79 per cent) had taken to ghost retail spaces,” he ation of studios, galleries, velopment plan released councils. up the ‘Percent for Art’ pol- said. rehearsal or performance earlier this year suggested RECHABITE Urban planning and de- icy. RobertsDay Perth prin- “Now we want to take spaces.” vacant stores be used for sign practice RobertsDay cipal Peter Ciemitis said that astep further and ex- City of Perth Chair Com- art activities. BACK IN and visual artists group more than 210 public art- tend the definitions to in- missioner Andrew Ham- “Agreements with prop- Artsource developed apoli- works had been incorporat- cludeart in the broader mond said the City support- erty owners to activate va- cy in2007 that encouraged ed into buildings and pro- sense: studios, galleries, ed providing infrastructure cant shop fronts with arts SERVICE councils to use part of de- jects across Perth as a performing arts spaces, for performance and cre- and cultural content have Landmark reopens: velopment costs for public result. -

Fluiaflkperry Rhew '\ Chief, Administrative Appeals Office Page 2

U.S. Department of Homeland Security U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Ofice of,4dministrutive Appeals MS 2090 identitying deta deleted Washington, DC 20529-2090 prevent clearly unwarranted U. S. Citizenship invasion of persod privacy and Immigration PUBLTC COPY SRC 08 242 53636 PETITION: Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker as an Alien of Extraordinary Ability Pursuant to Section 203(b)(l)(A) of the Immigration and Nationality Act; 8 U.S.C. 5 1 153(b)(l)(A) ON BEHALF OF PETITIONER: INSTRUCTIONS: This is the decision of the Administrative Appeals Office in your case. All documents have been returned to the office that originally decided your case. Any further inquiry must be made to that office. If you believe the law was inappropriately applied or you have additional information that you wish to have considered, you may file a motion to reconsider or a motion to reopen. Please refer to 8 C.F.R. 5 103.5 for the specific requirements. All motions must be submitted to the office that originally decided your case by filing Form I-290B, Notice of Appeal or Motion, with a fee of $585. Any motion must be filed within 30 days of the decision that the motion seeks to reconsider or reopen, as required by 8 C.F.R. fj 103.5(a)(l)(i). fLUIaflkPerry Rhew '\ Chief, Administrative Appeals Office Page 2 DISCUSSION: The employment-based immigrant visa petition was denied by the Director, Texas Service Center, on June 10, 2009, and is now before the Administrative Appeals Office on appeal. The appeal will be dismissed. -

The Game Changers SBS Learn Classroom Resource Years 5 – 8

The Game Changers SBS Learn Classroom Resource Years 5 – 8 Encouraging inclusivity and excellence in sport inspired by the INAS Global Games SBS is the official media and education partnerpage of 1 the INAS Global Games 2019. How to Use this Resource This resource is tailored to Years 5 to 8. It links to subjects including: English, Humanities and Social Sciences, Health and Physical Check out SBS Sport for games and news Education and Mathematics (see page 21 for a full list of Australian coverage, highlights Curriculum links). and live streaming. Visit sbs.com.au/sport for more information. This resource is led by four key concepts: 1. The INAS Global Games- Brisbane 2019 2. Athletic Excellence - Persistence, Commitment, Cover image: Resilience and Success Alberto Campbell- Staines. Alberto is 3. Inclusivity a Jamaican born, Australian elite 4. Communication athlete. He represents Australia as an Athlete With Disability (AWD) The INAS Global Games (GG2019) is a world-class sporting (T20 category) for competition that represents the peak of sporting achievement. 200m, 400m & 800m. Learn more about him Held once every four years, the Global Games sees competitors on page 8. from up to 80 countries going for gold and vying for the honour of being recognised as the best in their field. INAS is the recognised International Sport Organisation for athletes with an intellectual impairment and a full member of the International Paralympic Committee. Further classroom materials are available at: sbs.com.au/learn/the-game-changers Any questions about this resource? Contact [email protected] SBS acknowledges the traditional owners of Country throughout Australia. -

Broadcast of the World Taekwondo Grand Prix 2018

BROADCAST OF THE WORLD TAEKWONDO GRAND PRIX 2018 & WORLD TAEKWONDO CHAMPIONSHIPS 2019 INVITATION TO TENDER APRIL 2018 1 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction to Taekwondo ........................................................................................ 4 1.2 Taekwondo in Great Britain ........................................................................................ 4 1.3 Taekwondo Events Background .................................................................................. 5 1.4 Event Stakeholders ...................................................................................................... 5 2. TENDER REQUIREMENTS ....................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Vision, Mission & Objectives ....................................................................................... 6 2.2 Budget ......................................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Presentation ................................................................................................................ 7 3. WORLD TAEKWONDO GRAND PRIX 2018 .............................................................................. 8 3.1 Supporting Background Information .......................................................................... 8 3.2 Core Event Format ..................................................................................................... -

Ideals and Significance of the Paralympics: Observations from Temporal and Spatial Dimensions

Ideals and Significance of the Paralympics: Observations from Temporal and Spatial Dimensions Ideals and Significance of the Paralympics: Observations from Temporal and Spatial Dimensions Kazuo OGOURA Introduction As the Paralympics becomes more widely recognized and the public’s knowledge and interest grows, Paralympic competitions are, in part, starting to be commercialized and made into a form of entertainment. The current situation calls for a re-evaluation of what has been considered as the essential significance and effect of the Paralympic Games and the Paralympic Movement on society. In other words, there is an increasing need to look back on the history of the Paralympics to examine its original significance and ideals and, at the same time, to re-evaluate or re-examine the significance and ideals of the Paralympics through comparisons with similar international games and movements. From this perspective, this article will attempt to revisit the original ideals of the Paralympics and to look back on the history of the Paralympics. It will also discuss the significance and ideals of the Paralympics from social and international perspectives, in particular through comparisons with other international disability sports competitions: the Deaflympics, Special Olympics, the VIRTUS(previously INAS) Global Games for persons with intellectual disability, and the Invictus Games. The observation and analysis will focus on Paralympic ideals through the following eight dimensions:(1) as symbolized by the Paralympic symbol;(2) the slogans of the Paralympic Games;(3) the words of Sir Ludwig Guttmann;(4) the speeches at the opening and closing ceremonies; (5) the stage performances at the opening and closing ceremonies, medals, and songs;(6) the achievements of the recipients of the Whang Youn Dai Achievement Award; (7) comparison with major international disability sports competitions; and(8) comparison with the ideals of Japan’s National Sports Festival for People with Disabilities. -

2019 World Taekwondo Event Calendar (Subject to Change) ※ Event Grade Will Be Decided Based on the Result of 2018 Event Evaluation and Announced in November

2019 World Taekwondo Event Calendar (subject to change) ※ Event grade will be decided based on the result of 2018 event evaluation and announced in November. Date Event Place February 1-2 PARA KYORUGI 8th World Para-Taekwondo Championships Antalya, Turkey February 3 SENIOR KYORUGI Cyprus Open Larnaka, Cyprus February 4-9 TBD 4th WT President's Cup - European region Antalya, Turkey February 9-10 POOMSAE French Poomsae Open 2019 Lille, France February 11-12 CADET & JUNIOR February 13-14 SENIOR KYORUGI Turkish Open 2019 Antalya, Turkey February 15-16 POOMSAE February 22-23 SENIOR KYORUGI 7th Fujairah Open Fujairah, UAE February 23 SENIOR KYORUGI Slovenia Open 2019 Ljubljana, Slovenia February 21-22 CADET February 23-24 SENIOR KYORUGI Egypt Open Hurghada, Egypt February 26-27 SENIOR KYORUGI 9th Asian Taekwondo Clubs Championships Kish Island, Iran February 28-March 3 TBD European Clubs Championships Thessaloniki, Greece February 28-March 1 SENIOR KYORUGI March 2 JUNIOR 3rd WT President's Cup - Asian region Kish Island, Iran March 3 POOMSAE March 3 PARA KYORUGI March 2-3 SENIOR KYORUGI Sofia Open 2019 Sofia, Bulgaria March 4-5 SENIOR KYORUGI 30th Fajr Open Kish Island, Iran Santo Domingo, Dominican March 8 PARA KYORUGI Qualification tournament for the Lima 2019 Parapan American Games Republic March 9 SENIOR KYORUGI Dutch Open Taekwondo Championships 2019 Eindhoven, Netherlands March 10 CADET & JUNIOR March 16 SENIOR KYORUGI Belgian Open 2019 Lommel, Belgium March 17 CADET & JUNIOR March 30 SENIOR KYORUGI German Open 2019 Hamburg, Germany March