Hsinchu Technopolis: a Sociotechnical Imaginary Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Science Parks to Innovation Districts

From Science Parks to Innovation Districts Research Facility Development in Legacy Cities on the Northeast Corridor Working Paper 2015/008 August 2015 Eugenie L. Birch Lawrence C. Nussdorf Professor of Urban Research Department of City and Regional Planning School of Design Co-Director, Penn Institute for Urban Research University of Pennsylvania Contact Information: [email protected] Understanding our cities…. Understanding our world From Science Parks to Innovation Districts 2 Introduction Research and development (R&D) drives advanced economies worldwide. It is this that provides the foundation for the new knowledge, products, and processes that, in turn, become new industries, create jobs and serve as the source of economic growth. Key areas for R&D are in what is called the knowledge and technology industries (KTI) that consist of high technology manufacturing (e.g. aircraft, spacecraft, pharmaceuticals) and knowledge-intensive services (commercial business, financial and communication services). KTI, which account f or 27% of the worldwide Gross Domestic Product (GDP), are extremely important to the United States, in particular, representing 40% of the U.S. GDP. In fact, the U.S is the world’s largest KTI producer – contributing 27% of the total HT manufacturing and 32% of the KI services.1 In order to grow and maintain these positions, the United States, like its peers in Europe and Asia who are also large contributors, has built an extensive R&D infrastructure composed of three strong players: the private sector, the public sector and universities. In terms of expenditures and numbers of employees, the private sector dominates the R&D enterprise, but the university sector, largely funded by the US government, is also an important component both directly and indirectly. -

Body Donation Program

Body Donation Program The School of Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide operates a central mortuary facility on behalf of the Universities in South Australia for the acceptance of all bodies donated to science and controls the transfer of anatomical resources to licensed schools of anatomy within the State and Commonwealth in support of teaching, training, scientific studies and research. School of Medical Sciences Body Donation Program 2 Donating your body to science is one of the greatest Q1: What is the relevant State legislation that gifts one can give to make a lasting contribution to the allows for a person to donate their body to education and training of our current & future health science? professionals and to advance science through research. Historically, South Australians have been most generous In South Australia, the Transplantation and Anatomy in their support of our Body Donation Program and we Act, 1983*, Part V, allows members of the public to consistently have one of the highest donation rates per unconditionally donate their body for use in teaching, training, scientific studies and research, in any licensed capita in Australasia. institution in the Commonwealth. The opportunity to be able to dissect the human body is * Copies of the Transplantation and Anatomy Act, 1983 a privilege not available in many parts of the world and can be obtained from the internet at: this is reflected through the quality of our graduates and the world class training and research conducted within http://www.legislation.sa.gov.au the Universities in South Australia. Q2: How do I register my intention to donate my This leaflet will provide you and your family with detailed body to science? answers to the most common questions we are asked about the donation of one’s body to science. -

Certificate of Approval

Certification date: 10 May 2021 Expiry date: 9 May 2024 Certificate number: 10358798 IATF Certificate number: 0398565 Certificate of Approval This is to certify that the Management System of: NXP USA, Inc. 10, Jing 5th Road, N.E.P.Z, Kaohsiung 81170, Taiwan has been approved by Lloyd's Register to the following standards: IATF 16949:2016 Approval number(s): IATF 16949 – 0078056 This certificate is valid only in association with the certificate schedule bearing the same number on which the locations applicable to this approval are listed. The scope of this approval is applicable to: Design and Manufacture of Semiconductors. Cliff Muckleroy Area Operations Manager Americas Issued by: Lloyd's Register Quality Assurance Limited Lloyd's Register Group Limited, its affiliates and subsidiaries, including Lloyd's Register Quality Assurance Limited (LRQA), and their respective officers, employees or agents are, individually and collectively, referred to in this clause as 'Lloyd's Register'. Lloyd's Register assumes no responsibility and shall not be liable to any person for any loss, damage or expense caused by reliance on the information or advice in this document or howsoever provided, unless that person has signed a contract with the relevant Lloyd's Register entity for the provision of this information or advice and in that case any responsibility or liability is exclusively on the terms and conditions set out in that contract. Issued by: Lloyd's Register Quality Assurance Limited, 1 Trinity Park, Bickenhill Lane, Birmingham B37 7ES, United Kingdom Page 1 of 5 Approval number(s): 0078056 IATF Certificate number: 0398565 Certificate Schedule Location Activities NXP Semiconductors Taiwan Ltd. -

KEELUNG, TAIWAN Chiufen Walking Tour Glimpse a Piece of Taiwan's

KEELUNG, TAIWAN Chiufen Walking Tour Glimpse a piece of Taiwan’s past on a guided walking tour of Chiufen—a former gold mining village nestled on a mountainside. The gold ... VIEW DETAILS Book now Login to add to Favorites Email Excursion Approximately 4½ Hours National Palace Museum, Chiang Kai-Shek & Temples Take in Taiwan’s incredible history with this visit to some of Taipei's most extraordinary sights. Your journey commences with a relaxing drive from Keelung City, Taiwan's second-largest port, to the slopes of the Qing Mountain. Here you will visit the Martyrs' Shrine—a stately monument constructed in 1969 to honor the 330,000 brave men who sacrificed their lives in key battl... VIEW DETAILS Book now Login to add to Favorites Email Excursion Approximately 8¼ Hours Taipei On Your Own Design your own adventure in the exciting city of Taipei. Begin with a picturesque drive from Taiwan's second-largest port, Keelung City, to Taipei. Along the way, take in the country's lush green hill scenery. Arriving in the bustling city of Taipei, the political, cultural and economic center of Taiwan, you will marvel at the endless motorcycles, cars and buses buzzing about on the streets an... VIEW DETAILS Book now Login to add to Favorites Email Excursion Approximately 8 Hours Yang Ming Shan Hot Springs & Yehliu Geographic Park Indulge in Taiwan's natural wonders—towering mountains in green hues, lush mystical forests, deep rivers and gorges, steaming natural hot springs and moon-like landscapes. Accompanied by a knowledgeable guide, you will set out on a scenic journey across some gorgeous countryside. -

New Taipei City

Data provided for the www.cdp.net CDP Cities 2015 Report New Taipei City Written by Report analysis & information In partnership with design for CDP by New Taipei City in Context 04 New Taipei City in Focus 06 Introduction 08 Governance 10 Risks & Adaptation 16 Opportunities 24 Emissions - Local Government 28 Emissions – Community 38 Strategy 48 CDP, C40 and AECOM are proud to present results from our fifth consecutive year of climate change reporting for cities. It was an impressive year, with 308 cities reporting on their climate change data (six times more than the number that was reported in the survey’s first year of 2011), making this the largest and most comprehensive survey of cities and climate change published to date by CDP. City governments from Helsinki to Canberra to La Paz participated, including over 90% of the membership of the C40 – a group of the world’s largest cities dedicated to climate change leadership. Approximately half of reporting cities measure city-wide emissions. Together, these cities account for 1.67 billion tonnes CO2e, putting them on par with Japan and UK emissions combined. 60% of all reporting cities now have completed a climate change risk assessment. And cities reported over 3,000 individual actions designed to reduce emissions and adapt to a changing climate. CDP, C40 and AECOM salute the hard work and dedication of the world’s city governments in measuring and reporting these important pieces of data. With this report, we provide city governments the information and insights that we hope will assist their work in tackling climate change. -

Taiwan Factsheet

UPS TAIWAN FACTSHEET FOUNDED 28 August 1907, in Seattle, Washington, USA ESTABLISHED IN TAIWAN 1988 WORLD HEADQUARTERS Atlanta, Ga., USA ASIA PACIFIC HEADQUARTERS Singapore UPS TAIWAN OFFICE UPS International Inc., Taiwan Branch, 2F, 361 Ta Nan Road, Shih Lin District, Taipei 11161, Taiwan TRANS PACIFIC HUB to No. 31 Export Gate, Taipei Air Cargo Terminal, CKS Airport, P.O. Box 073, 10- 1, Hangchin North Rd, Dayuan, Taoyuan City, Taiwan MANAGING DIRECTOR, UPS TAIWAN Sam Hung WORLD WIDE WEB ADDRESS ups.com/tw/en GLOBAL VOLUME & REVENUE 2019 REVENUE US$74 billion 2019 GLOBAL DELIVERY VOLUME 5.5 billion packages and documents DAILY GLOBAL DELIVERY VOLUME 21.9 million packages and documents DAILY U.S. AIR VOLUME 3.5 million packages and documents DAILY INTERNATIONAL VOLUME 3.2 million packages and documents EMPLOYEES More than 860 in Taiwan; more than 528,000 worldwide BROKERAGE OPERATIONS & OPERATING FACILITIES 14 (1 hub, 8 service centers, 4 LG warehouses and 1 Forwarding office) POINTS OF ACCESS 1,145 (UPS Service Centres, I-BOX e-lockers and FamilyMart convenience store outlets islandwide) DELIVERY FLEET 128 (motorcycles, vans and feeder vehicles) AIRPORTS SERVED 1 (Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport – TPE) UPS FLIGHTS 22 weekly flights to and from Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport (TPE) SEAPORTS SERVED 2 (Keelung Seaport and Kaohsiung Seaport) SERVICES Small Package Contract Logistics Enhanced Services Technology Solutions UPS Worldwide Express Distribution UPS Returns® UPS Billing Data and Billing Plus® Service Part Logistics -

Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Transformation of Fort San Domingo in Tamsui, Taiwan, from the Perspective of Cultural Imagination

This paper is part of the Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Defence Sites: Heritage and Future (DSHF 2016) www.witconferences.com Analysis of the spatiotemporal transformation of Fort San Domingo in Tamsui, Taiwan, from the perspective of cultural imagination C.-Y. Chang Ministry of the Interior, Architecture and Building Institute, Taiwan, ROC Abstract The timeline of transformation of Fort San Domingo shows that between the 1630s and 1860s it was used as a military defense; from the 1860s–1970s as a foreign consulate and then from the 1980s–2010s as a historical site. We can see different and contradictory explanations of the cultural imagination of remembrance, exoticism and the symbolism of anti-imperialism from the historical context of this military building. Keywords: spatiotemporal transformation, Fort San Domingo, Tamsui, cultural imagination. 1 Introduction Fort San Domingo is rather young compared to forts built in Europe, yet it has a different historical meaning for this island located in Eastern Asia. Fort San Domingo (聖多明哥城) was one of the earliest Grade I heritage sites first appointed under the Cultural Heritage Preservation Act in 1982. It is the most well preserved fortress that can be dated back to the golden age of expeditions made by the Dutch East India Company during the colonial era. Moreover, Fort San Domingo is also the first heritage that has been transformed into a modern museum. Named the Tamsui Historical Museum of New Taipei City, the fort and its surrounding historical buildings were listed as a Potential World Heritage Site in Taiwan by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage. -

Analysis of Residential and Auto Break-In Records in Taipei City

Portland State University PDXScholar Engineering and Technology Management Student Projects Engineering and Technology Management Winter 2018 Analysis of Residential and Auto Break-in Records in Taipei City Afnan Althoupety Portland State University Aishwarya Joy Portland State University Juchun Cheng Portland State University Priyanka Patil Portland State University Tejas Deshpande Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/etm_studentprojects Part of the Applied Statistics Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Althoupety, Afnan; Joy, Aishwarya; Cheng, Juchun; Patil, Priyanka; and Deshpande, Tejas, "Analysis of Residential and Auto Break-in Records in Taipei City" (2018). Engineering and Technology Management Student Projects. 1943. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/etm_studentprojects/1943 This Project is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Engineering and Technology Management Student Projects by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Analysis of Residential and Auto Break-in Records in Taipei City Course: ETM 538 Term: Winter 2018 Instructors: Daniel Sagalowicz, Mike Freiling Date: 03/09/2018 Authors:Afnan Althoupety , Aishwarya Joy , Juchun Cheng , Priyanka Patil , Tejas Deshpande 1 1. Introduction Taipei City is the capital of Taiwan. It has population of 2.7 million living in the city area of 271 km2 (104 mi2). There are totally 12 administrative districts in this city. To maintain the safety of the city, Taipei City Police Bureau has arranged regular patrol routes with focus on the high-risk area where residential and auto break-in occurs. -

Annual Report

Top Ranking Report Annual Report Architectural Record ENR VMSD Top 300 Architecture Top 150 Global Top Retail Design Firms: Design Firms: Firms of 2014: # #1 Firm Overall #1 Architecture Firm #1 Firm Overall Building Design ENR Interior Design Message from the Board of Directors 2014 World Top 500 Design Firms: Top 100 Giants: Architecture 100 Most #1 Architecture Firm #1 Architecture Firm Admired Firms: Gensler is1 a leader among the #1 in Corporate Office As we celebrate our 50th anniversary, we world’s architecture and design #1 US Firm #1 in Retail #4 Global Firm #1 in Transportation firms. Here’s how we ranked in #1 in Government look forward to more record-setting years, our industry in 2014. #1 in Cultural thanks to our great client relationships and extraordinary people around the world. Financial Report Our financial performance and recognition throughout the We’re entering our 50th year stronger than ever. Financially strong and debt-free, we contributed industry are indications of the breadth of our practice, our global In 2014, our global growth continued apace $38.5 million in deferred compensation to our reach, and the long-standing trust of our clients. with our clients as they entrusted us with new employees through our ESOP, profit-sharing, and challenges and led us to new locations. Our international retirement plans. We made strategic expanded Gensler team of 4,700+ professionals investments in our research and professional We’ve broadened our services to 27 now work from 46 different offices. With their development programs, along with upgrades to practice areas, with total revenues help, we completed projects in 72 countries and our design-and-delivery platform and the tools for the year setting a new record $ increased our revenues to $915 million—a record and technology to support it. -

The Ambassador Hotel Hsinchu Gets Under Way

THE AMBASSADOR HOTEL 2014 BUSINESS REVIEW Stock Code::2704 Business Strategy 1.To follow the successful business brand model of the amba with concepts of technology, environmental protection and innovation. 2.To build the shared service center to enhance the revenue of company effectively. 3.In order to be more competitive in the market of food and beverage we plan to remodel the restaurant as one of improvement. 1 Inbound visitor statistics Place of residence Item 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014/1-2Q Visitors 972,123 1,630,735 1,784,185 2,586,428 2,874,702 1,961,929 Mainland China Growth Rate 195.30% 67.75% 9.41% 44.96% 11.15% 38.45% Visitors 718,806 794,362 817,944 1,016,356 1,183,341 659,487 Hong Kong/Macao Growth Rate 16.19% 10.51% 2.97% 24.26% 16.43% 18.08% Visitors 1,000,661 1,080,153 1,294,758 783,118 Japan 1,432,315 1,421,550 Growth Rate -7.92% 7.94% 19.87% 10.62% -0.75% 18.55% Visitors 167,641 216,901 242,902 259,089 351,301 262,814 Korea Growth Rate -33.55% 29.38% 11.99% 6.66% 35.59% 79.81% Visitors 795,853 1,059,909 1,124,421 1,179,496 1,307,892 695,485 Asia Growth Rate -0.39% 32.24% 5.99% 4.90% 10.89% 16.83% Visitors 442,036 474,709 495,136 497,597 502,446 277,455 America Growth Rate -4.17% 7.39% 4.30% 0.50% 0.97% 14.07% Visitors 197,070 203,301 212,148 218,045 223,062 128,723 Europe Growth Rate -1.91% 3.16% 4.35% 2.78% 2.30% 21.44% Visitors 66,173 71,953 70,540 75,414 77,722 46,049 Oceania Growth Rate -3.47% 8.73% -1.96% 6.91% 3.06% 25.21% Visitors 7,735 8,254 8,938 8,865 8,795 4,825 Africa Growth Rate -8.99% 6.71% 8.29% -0.82% -

Contact Information

Contact Information Corporate Headquarters & Fab 12A TSMC Korea Limited 8, Li-Hsin Rd. 6, Hsinchu Science Park, Hsinchu 30078, Taiwan, R.O.C. 15F, AnnJay Tower, 208, Teheran-ro, Gangnam-gu Tel: +886-3-5636688 Fax: +886-3-5637000 Seoul 135920, Korea Tel: +82-2-20511688 Fax: +82-2-20511669 R&D Center & Fab 12B 168, Park Ave. II, Hsinchu Science Park, Hsinchu 30075, Taiwan, R.O.C. TSMC Liaison Office in India Tel: +886-3-5636688 FAX: +886-3-6687827 1st Floor, Pine Valley, Embassy Golf-Links Business Park Bangalore-560071, India Fab 2, Fab 5 Tel: +1-408-3827960 121, Park Ave. 3, Hsinchu Science Park, Hsinchu 30077, Taiwan, R.O.C. Fax: +1-408-3828008 Tel: +886-3-5636688 Fax: +886-3-5781546 TSMC Design Technology Canada Inc. Fab 3 535 Legget Dr., Suite 600, Kanata, ON K2K 3B8, Canada 9, Creation Rd. 1, Hsinchu Science Park, Hsinchu 30077, Taiwan, R.O.C. Tel: +613-576-1990 Tel: +886-3-5636688 Fax: +886-3-5781548 Fax: +613-576-1999 Fab 6 TSMC Spokesperson 1, Nan-Ke North Rd., Tainan Science Park, Tainan 74144, Taiwan, R.O.C. Name: Lora Ho Tel: +886-6-5056688 Fax: +886-6-5052057 Title: Senior Vice President & CFO Tel: +886-3-5054602 Fax: +886-3-5637000 Fab 8 Email: [email protected] 25, Li-Hsin Rd., Hsinchu Science Park, Hsinchu 30078, Taiwan, R.O.C. Tel: +886-3-5636688 Fax: +886-3-5662051 TSMC Deputy Spokesperson/Corporate Communications Name: Elizabeth Sun Fab 14A Title: Director, TSMC Corporate Communication Division 1-1, Nan-Ke North Rd., Tainan Science Park, Tainan 74144, Taiwan Tel: +886-3-5682085 Fax: +886-3-5637000 R.O.C. -

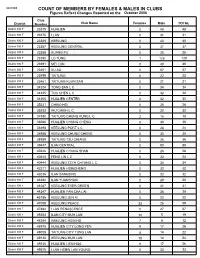

Count of Members by Females & Males in Clubs

GN1569 COUNT OF MEMBERS BY FEMALES & MALES IN CLUBS Figures Reflect Changes Reported on the October 2006 Club District Number Club Name Females Male TOTAL District 300 F 23375 HUALIEN 0 48 48 District 300 F 23376 I LAN 0 31 31 District 300 F 23386 KEELUNG 0 40 40 District 300 F 23387 KEELUNG CENTRAL 0 37 37 District 300 F 23388 KUANG FU 0 25 25 District 300 F 23390 LO TUNG 1 128 129 District 300 F 23391 MEI LUN 0 40 40 District 300 F 23401 SU AO 0 57 57 District 300 F 23459 TAITUNG 0 22 22 District 300 F 23461 TAITUNG KUAN SAN 0 21 21 District 300 F 34324 TONG SAN L C 0 34 34 District 300 F 34325 TOU CHEN L C 0 32 32 District 300 F 34406 HUALIEN CENTER 0 32 32 District 300 F 35231 CHIAO HSI 0 26 26 District 300 F 35233 WU CHIEH L C 0 32 32 District 300 F 37380 TAITUNG CHENG KUNG L C 2 16 18 District 300 F 38086 HUALIEN CHUNG CHENG 0 30 30 District 300 F 38498 KEELUNG PORT L C 0 24 24 District 300 F 38988 KEELUNG CHUNG CHENG 0 30 30 District 300 F 38989 TAITUNG TZU CHIANG 0 36 36 District 300 F 39447 ILAN CENTRAL 0 80 80 District 300 F 40326 HUALIEN CHUNG SHAN 0 26 26 District 300 F 40443 FENG LIN L C 0 23 23 District 300 F 40444 KEELUNG TZYH CHYANG L C 0 34 34 District 300 F 42211 HUALIEN HSINCHENG 0 32 32 District 300 F 43036 ILAN SANHSING 0 32 32 District 300 F 43382 ILAN YUANSHAN 0 20 20 District 300 F 44087 KEELUNG EVER GREEN 0 41 41 District 300 F 44247 HUALIEN FAN CHA LAI 0 38 38 District 300 F 45186 KEELUNG JEN AI 0 22 22 District 300 F 47008 KEELUNG PEACE 33 26 59 District 300 F 47884 I LAN RENASCENCE 0 27 27 District 300 F 48383