Factions on the Venetian Terraferma During the Early Modern Period*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Venue Sheet

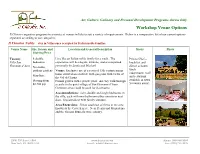

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Church History Building-In-Time

Church History http://journals.cambridge.org/CHH Additional services for Church History: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Building-in-Time: From Giotto to Alberti and Modern Oblivion. By Marvin Trachtenberg. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2010. xxvi + 490 pp. \$65.00 cloth. Caroline Bruzelius Church History / Volume 82 / Issue 02 / June 2013, pp 431 - 436 DOI: 10.1017/S0009640713000231, Published online: 20 May 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009640713000231 How to cite this article: Caroline Bruzelius (2013). Church History, 82, pp 431-436 doi:10.1017/ S0009640713000231 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CHH, IP address: 193.205.243.200 on 16 Sep 2013 BOOK REVIEWS AND NOTES 431 and polished over Bernard’s entire lifetime and the part cited could come from the 1140s like the other evidence that she cites. It is probably a misreading of the secondary source on the Order’s administration, that we read the statement by Kerr: “individual Cistercian houses were joined together in familial bonds and arranged in a hierarchy” (82). This is only partially correct, for a foremost principle of the Cistercian Charter of Charity (whatever its date) is that Cistercian abbeys and their abbots were to treat one another equally, unlike in the monarchical hierarchy of Cluny. Despite calling Cîteaux “the mother of us all,” there is no single abbot ruling the Order, but a collective head, the General Chapter of all abbots. The chapter on Cistercian spirituality, given the limited space, provides interesting evidence from saints’ lives about (often female) mystics who may have had ties to Cistercians. -

3 Architects, Antiquarians, and the Rise of the Image in Renaissance Guidebooks to Ancient Rome

Anna Bortolozzi 3 Architects, Antiquarians, and the Rise of the Image in Renaissance Guidebooks to Ancient Rome Rome fut tout le monde, & tout le monde est Rome1 Drawing in the past, drawing in the present: Two attitudes towards the study of Roman antiquity In the early 1530s, the Sienese architect Baldassare Peruzzi drew a section along the principal axis of the Pantheon on a sheet now preserved in the municipal library in Ferrara (Fig. 3.1).2 In the sixteenth century, the Pantheon was generally considered the most notable example of ancient architecture in Rome, and the drawing is among the finest of Peruzzi’s surviving architectural drawings after the antique. The section is shown in orthogonal projection, complemented by detailed mea- surements in Florentine braccia, subdivided into minuti, and by a number of expla- natory notes on the construction elements and building materials. By choosing this particular drawing convention, Peruzzi avoided the use of foreshortening and per- spective, allowing measurements to be taken from the drawing. Though no scale is indicated, the representation of the building and its main elements are perfectly to scale. Peruzzi’s analytical representation of the Pantheon served as the model for several later authors – Serlio’s illustrations of the section of the portico (Fig. 3.2)3 and the roof girders (Fig. 3.3) in his Il Terzo Libro (1540) were very probably derived from the Ferrara drawing.4 In an article from 1966, Howard Burns analysed Peruzzi’s drawing in detail, and suggested that the architect and antiquarian Pirro Ligorio took the sheet to Ferrara in 1569. -

Italy Travel and Driving Guide

Travel & Driving Guide Italy www.autoeurope. com 1-800-223-5555 Index Contents Page Tips and Road Signs in Italy 3 Driving Laws and Insurance for Italy 4 Road Signs, Tolls, driving 5 Requirements for Italy Car Rental FAQ’s 6-7 Italy Regions at a Glance 7 Touring Guides Rome Guide 8-9 Northwest Italy Guide 10-11 Northeast Italy Guide 12-13 Central Italy 14-16 Southern Italy 17-18 Sicily and Sardinia 19-20 Getting Into Italy 21 Accommodation 22 Climate, Language and Public Holidays 23 Health and Safety 24 Key Facts 25 Money and Mileage Chart 26 www.autoeurope.www.autoeurope.com com 1-800 -223-5555 Touring Italy By Car Italy is a dream holiday destination and an iconic country of Europe. The boot shape of Italy dips its toe into the Mediterranean Sea at the southern tip, has snow capped Alps at its northern end, and rolling hills, pristine beaches and bustling cities in between. Discover the ancient ruins, fine museums, magnificent artworks and incredible architecture around Italy, along with century old traditions, intriguing festivals and wonderful culture. Indulge in the fantastic cuisine in Italy in beautiful locations. With so much to see and do, a self drive holiday is the perfect way to see as much of Italy as you wish at your own pace. Italy has an excellent road and highway network that will allow you to enjoy all the famous sites, and give you the freedom to uncover some undiscovered treasures as well. This guide is aimed at the traveler that enjoys the independence and comfort of their own vehicle. -

Italy YOUR ITINERARY

Offered to the Students and Friends of Smith Preparatory Academy and FCCPSA The Splendors of Italy Verona-Vicenza-Venice-Padua-Florence-Siena-San Gimignano-Rome* February 24 – March 7, 2022 YOUR ITINERARY Together with Leader Michael Phillips: Headmaster of Smith Preparatory Academy and a Director of FCCPSA. $ from Orlando* February 24–March 7, 2022 Tour Code: 222118 On February 24th, you will depart Orlando to spend 12 wonderful days discovering the splendors of Italy. Fantastic excursions, cultural encounters, historical sites, delicious food and exotic shopping make this trip exciting and rewarding. Bring these amazing memories home with you on March 7th. SPACE ON THE TOUR IS LIMITED, SO DON’T DELAY! PLEASE RETURN YOUR ONLINE APPLICATION AND $100 DEPOSIT TO EATOURS.COM BY AND RECEIVE A FREE GONDOLA RIDE IN VENICE! Verona, Vicenza, Padua & Venice February 24-February 27, 2022 Upon arrival February 25th, you will transfer to Verona, a delightful city for enjoying a guided tour* including the Roman Arena* and Juliet’s balcony before continuing to your hotel in Vicenza. Complete the afternoon exploring the city before dinner. The morning of February 26th, you will depart Vicenza on a scenic train* for an excursion to Padua! Padua is an old university town with an illustrious academic history that is rich in art and architecture. Upon arrival to Padua, a guided tour of the city* is planned, including the Scrovengi Chapel* and St. Anthony’s Basilica*. Dedicate this afternoon to exploring Vicenza where you may optionally visit Teatro Olympico. Your adventure continues February 27th, on a picturesque train* ride excursion to Venice! Enjoy a guided tour of the city* where you may see sights such as St. -

INTRODUCTION Hospital

INTRODUCTION Hospital Pratical Tips INTRODUCTION CONTENTS WELCOME A brief introduction to USAG Italy 01 | and Family and MWR. VICENZA FACILITIES Information about on-post 02-21 | facilities and services in Vicenza. VICENZA POST MAPS General maps of posts in Vicenza FACILITY INFORMATION 22-23 | with MWR facilities highlighted. A snapshot of everything Family 04 | and MWR offers in USAG Italy. ALL THINGS TRAVEL Information on licenses, traveling, 24-25 | passports and more. FURRY FRIENDS A glimpse of useful information 27 | and tidbits for pet owners. ITALIAN INFO USEFUL INFORMATION Helpful Italian words and phrases Find out helpful information about 28-29 | and local information/traditions. 24 | the community and more! CITIES, MAPS & MORE Get inspired to travel outside the 30-57 | gate with these guides and maps. DARBY FACILITIES Information about on-post 58-63 | facilities and services in Darby. DARBY ON-POST MAP CITY GUIDES A general map of Darby with See a snapshot of cities and places 59 | MWR facilities highlighted. 30 | in and around USAG Italy. Cover Image: Verona, Italy “Go To Guide” designed by: Family and MWR Marketing (Richard Gerke, Beatrice Giometto, Alyssa Olson) Advertising Disclaimer: No federal, DoD or Army endorsement is implied. Interested in advertising with us? Contact Family and MWR Marketing at 0444-61-7992 or at 338-726-4361. INTRODUCTION WELCOME! A WORD FROM USAG ITALY FAMILY AND MWR Welcome to U.S. Army Garrison Italy! USAG Italy is a community of service members, civilians, family members, and Italian military and civilian employees. These Army locations cover a broad region south of the Alps that include: Caserma Ederle, Caserma Del Din and satellite locations around Vicenza, as well as Camp Darby, located in Livorno on Italy’s western coast. -

ENG AUTOBSPD 31 12 2018 Fascicolo Completo Bilancio

TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE BOARDS AND OFFICERS ........................................................................................................ 8 REPORT ON OPERATIONS ................................................................................................................................ 9 Overview ................................................................................................................................................................. 9 1 Business performance .................................................................................. 9 1.1 Results of operations ........................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Cash flows .............................................................................................................................................. 11 1.3 Financial position ................................................................................................................................. 12 2 Motorway operation .....................................................................................13 2.1 Traffic ....................................................................................................................................................... 13 2.2 Accident rates ....................................................................................................................................... 17 2.3 Toll rates ................................................................................................................................................ -

Guide to Siracusa

how to print and assembling assembleguide the the guide f Starting with the printer set-up: Fold the sheet exactly in the select A4 format centre, along an imaginary line, and change keeping the printed side to the the direction of the paper f outside, from vertical to horizontal. repeat this operation for all pages. We can start to Now you will have a mountain of print your guide, ☺ flapping sheets in front of you, in the new and fast pdf format do not worry, we are almost PDF there, the only thing left to do, is to re-bind the whole guide by the edges of the longest sides of the sheets, with a normal Now you will have stapler (1) or, for a more printed the whole document aesthetic result, referring the work to a bookbinder asking for spiral binding(2). Congratulations, you are now Suggestions “EXPERT PUBLISHERS”. When folding the sheet, we would suggest placing pressure with your fingers on the side to be folded, so that it might open up, but if you want to permanently remedy this problem, 1 2 it is enough to apply a very small amount of glue. THESIRACUSA CITY GUIDE © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism © 2005 Netplan srl. All rights reserved. © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism All material on this document is © Netplan. THE SIRACUSA CITY GUIDE 1 Summary THINGS TO KNOW 3 History and culture THINGS TO SEE 4 Churches and Museums 5 Historical buildings and monuments 6 Places and charm THINGS TO TRY 7 Eating and drinking 8 Shopping 9 Hotels and lodgings THINGS TO EXPERIENCE 10 Events 11 La Dolce Vita ITINERARIES 12 A special day 14 Trip outside the city: Noto 15 The Vendicari reserve © Netplan - Internet solutions for tourism THE SIRACUSA CITY GUIDE / THINGS TO KNOW 3 4 THE SIRACUSA CITY GUIDE / THINGS TO SEE History and culture Churches and Museums lost its independence and liberty after it was was the Cathedral of Siracusa for a long conquered by the Roman Empire. -

GOLDSCHMIED & CHIARI Sara Goldschmied

GOLDSCHMIED & CHIARI Sara Goldschmied (b. 1975, Vicenza, Italy) and Eleonora Chiari (b. 1971, Rome, Italy) Live and work in Milan, Italy SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Vice Versa, Kristen Lorello, New York, NY Untitled Views, Renata Fabbri Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy 2014 Goldschmied & Chiari: Untitled Portraits, Kristen Lorello, New York La democrazia è illusione, curated by Ilaria Bonacossa, Villa Croce, Museum of Contemporary Art, Genova (IT) La démocratie est illusion, curated by Etienne Bernard, Centre d’Art Contemporaine Passerelle, Brest (FR) 2013 Hiding the Elephant, Edicola Notte, Rome, (IT) 2011 Nympheas, curated by Paola Ugolini and Camilla Grimaldi, Icario Arte, Montepulciano, (IT) 2010 Fumo negli occhi, Gonzalez y Gonzalez Gallery, Santiago, Chile Genealogy of Damnatio Memoriae, Atelier House, Museion Museum of contemporary art, Bolzano, (IT) 2009 Roommates, curated by Cecilia Canziani, Macro Museum of contemporary art, Rome, (IT) 2008 Dump Queen, Galerie Elaine Levy Project, Bruxelles, (BE) Dump Queen, curated by Ludovico Pratesi and Paola Ugolini, Centro Arti Visive Pescheria, Pesaro, (IT) Cosmic Love, Galleria VM21 Arte contemporanea, Rome, (IT) 2007 Polly Apfelbaum, goldiechiari, Ann Veronica Janssens, curated by Etienne Ficheroulle, Galerie Blancpain, Geneva, (CH) 2006 Welcome, Spencer Brownstone Gallery, New York, (USA) Enjoy, Galerie Elaine Levy Project, Bruxelles, (BE) 2005 Nympheas , Galleria VM21 Arte contemporanea, Rome, (IT) Bu Colics, Galerie M3, Antwerpen, (BE) 2002 Blind Date, curated by Alessandra Galletta, Viafarini, -

Het Park Adda Noord - Deel 2

Jaargang 2016, nr. 7 1 Tekst en foto’s Ruud en Ina Metselaar – www.comomeerinfo.nl Het park Adda Noord - Deel 2. Crespi d’Adda Het park Vanaf Lecco staat het stroomgebied van de Adda over een lengte van circa 40 km bekend als het Parco Adda Nord. Sinds 1983 is dit een beschermd gebied met een totaal oppervlak van 7000 ha. Het gebied is landschappelijk zeer aantrekkelijk, maar is bovendien interessant door verschillende ingenieurswerken, zoals de kanalen en sluizen van Leonardo da Vinci, de waterkrachtcentrales en het industriedorp Crespi d’Adda. Nieuwsbrief 5(2016) was geheel gewijd aan een aantal van de bezienswaardigheden langs de rivier en in dit tweede deel beschrijf ik het industriedorpdorp. Crespi is een van de weinige dorpen die geheel rond een industrie zijn gebouwd en de oorspronkelijke gedaante hebben behouden. Het staat om die reden sinds 1995 op de Unesco lijst van Werelderfgoederen. Crespi d’Adda ligt in de gemeente Capriate San Servasio, tegenover Trezzo sull’Adda. Van Lecco is de kortste route 35 km over de SP72 tot Airuno, dan SP56 en SP169 naar Calusco d’Adda, en SP170 naar Crespi d’Adda. Ca 1 uur rijden. Het alternatief is de autostrada r. Milaan, dan autostrada A4 r. Venetië tot afslag Capriate, daarna bordjes Crespi d’Adda volgen, totaal 69 km. Volgens de routeplanner is dit 1 minuut sneller maar toen ik het op een zondagmiddag reed stond ik wel minstens een half uur in de file rond Milaan – dus niet aanbevolen. In de maanden april tot september moet u de auto achterlaten op het parkeerterrein vóór het dorp op ca 800 m buiten Crespi. -

The Muqarnas Wooden Ceiling and the Nave Roofing in the Palatina Chapel of Palermo: Geometries, Failures and Restorations

From Material to Structure - Mechanical Behaviour and Failures of the Timber Structures ICOMOS IWC - XVI International Symposium – Florence, Venice and Vicenza 11th -16th November 2007 The Muqarnas Wooden Ceiling and the Nave Roofing in the Palatina Chapel of Palermo: Geometries, Failures and Restorations Mario Li Castri, Tiziana Campisi Dipartimento di Progetto e Costruzione Edilizia - University of Palermo Relationships between basic geometry, mechanical and damage behaviours in muqarnas wooden ceiling of the Palatina Chapel in Palermo Complex wooden carpentries, as that of muqarnas ceiling in the Palatina Chapel of Palermo induce technicians and scientists to have a relationship with interesting study-cases, in which the aspect connected merely to basic geometries and volumes (particularly - for the examined case - the intrados and extrados surfaces, strongly plastic, corrugated and modelled), indissolubly integrate themselves with the adopted materials (above all, wood and iron), with constructive elements on a vast scale (we thought to the realization of principal and secondary bearing structure, of finishing and completing parts, useful to the intrados continuity), as they integrate themselves with detailed aspects (we cited the little wooden rods, joists, tablets and slats used to model now the muqarnas alveoluses, now the barrel vaults, the segmental domes or the vaults having a mixtilinear profile, etc.), and also with specific constructive technologies (particularly we refer to connection systems through nails and strips, permeation of structural elements, …, resulting very important and resolutive for a wooden carpentry so articulated, and that have to be extremely accurate and reliable, because of they constitute “sensible” points of efficacy and/or structural frailty, besides a punctual constraints). -

Historic Centre of Cordoba; Rock Art of the Mediterranean Basin on The

• Spain: Historic Centre of Cordoba; Rock Art of the Mediterranean Basin on the Iberian Peninsula; University and Historic Precinct of Alcalá de Henares; • United States of America: Monticello and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville; LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: • Brazil: Iguaçu National Park; • Mexico: Agave Landscape and Ancient Industrial Facilities of Tequila; Luis Barragán House and Studio; 6. Requests the States Parties which have not yet answered the questions raised in the framework of the Retrospective Inventory to provide all clarifications and documentation as soon as possible, and by 1 December 2015 at the latest, for their subsequent examination, if satisfactory, by the 40th session of the World Heritage Committee in 2016. 8E. ADOPTION OF RETROSPECTIVE STATEMENTS OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE Decision: 39 COM 8E The World Heritage Committee, 1. Having examined Document WHC-15/39.COM/8E.Rev, 2. Congratulates the States Parties for the excellent work accomplished in the elaboration of retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value for World Heritage properties located within their territories; 3. Adopts the retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value, as presented in the Annex of Document WHC-15/39.COM/8E.Rev, for the following World Heritage properties: AFRICA • Mozambique: Island of Mozambique; • Senegal: Djoudj National Bird Sanctuary; • United Republic of Tanzania: Stone Town of Zanzibar; ARAB STATES • Oman: Land of Frankincense; ASIA AND THE PACIFIC • India: Humayun’s Tomb, Delhi; Kaziranga