Unit 8: Consolidation of the British Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur's Ahoms

High Technology Letters ISSN NO : 1006-6748 The Forgotten Saga of Rangpur’s Ahoms - An Ethnographic Approach Barnali Chetia, PhD, Assistant Professor, Indian Institute of Information Technology, Vadodara, India. Department of Linguistics Abstract- Mong Dun Shun Kham, which in Assamese means xunor-xophura (casket of gold), was the name given to the Ahom kingdom by its people, the Ahoms. The advent of the Ahoms in Assam was an event of great significance for Indian history. They were an offshoot of the great Tai (Thai) or Shan race, which spreads from the eastward borders of Assam to the extreme interiors of China. Slowly they brought the whole valley under their rule. Even the Mughals were defeated and their ambitions of eastward extensions were nipped in the bud. Rangpur, currently known as Sivasagar, was that capital of the Ahom Kingdom which witnessed the most glorious period of its regime. Rangpur or present day sivasagar has many remnants from Ahom Kingdom, which ruled the state closely for six centuries. An ethnographic approach has been attempted to trace the history of indigenous culture and traditions of Rangpur's Ahoms through its remnants in the form of language, rites and rituals, religion, archaeology, and sacred sagas. Key Words- Rangpur, Ahoms, Culture, Traditions, Ethnography, Language, Indigenous I. Introduction “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.” -P.B Shelley Rangpur or present day Sivasagar was one of the most prominent capitals of the Ahom Kingdom. -

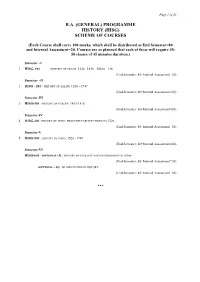

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

13 Chapter 05.Pdf

CHAPTERV THE BRITISH OCCUPATION OF ASSAM AND DISINTEGRATION OF THE OLD ORDER The Treaty of Yandabu (24th February, 1826) which marked the conclusion of the first Anglo-Burmese war also forms a dividing line between end of one age and the beginning of another in the history of Assam. Assam now entered into what can be termed as the modem age. Historically, political modernization is referred to the totality of changes in the political structure, 1 affected by major transformations in all aspects of administration. The advent of the British to ushered in radical changes in the entire pre-British political structure. This chapter is devoted to an analysis of the British system vis-a-vis that of the Ahom. It is, therefore, most relevant to recount Article 2 of the Treaty, which runs thus: "His Majesty, the King of Ava renounces all claims upon, and will abstain from all future interference with, the principalities of Assam and its dependencies, and also with the contiguous petty states of Cachar and Jyntea. With regard to Manipur it is stipulated that, should Gambhir Singh desire to return to that country, he shall be recognised by the King of Ava as Raja thereof'.2 The above Article does not bear any indirect or oblique recognition of the East India Company's right to establish its political control over the principalities of Assam, and Manipur. What in fact occured was that the East India Company 145 stepped in to fill the political vacuum created by the Burmese withdrawal. The British first settled the question of Manipur as the security in the North-East lay to a great extent on the establishment of a strong ruler in Manipur to serve as a buffer between the British Indian empire and Burma. -

1Edieval Assam

.-.':'-, CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION : Historical Background of ~1edieval Assam. (1) Political Conditions of Assam in the fir~t half of the thirt- eenth Century : During the early part of the thirteenth Century Kamrup was a big and flourishing kingdom'w.ith Kamrupnagar in the· North Guwahat.i as the Capital. 1 This kingdom fell due to repeated f'.1uslim invasions and Consequent! y forces of political destabili t.y set in. In the first decade of the thirteenth century Munammedan 2 intrusions began. 11 The expedition of --1205-06 A.D. under Muhammad Bin-Bukhtiyar proved a disastrous failure. Kamrtipa rose to the occasion and dealt a heavy blow to the I"'!Uslim expeditionary force. In 1227 A.D. Ghiyasuddin Iwaz entered the Brahmaputra valley to meet with similar reverse and had to hurry back to Gaur. Nasiruddin is said to have over-thrown the I<~rupa King, placed a successor to the throne on promise of an annual tribute. and retired from Kamrupa". 3 During the middle of the thirteenth century the prosperous Kamrup kingdom broke up into Kamata Kingdom, Kachari 1. (a) Choudhury,P.C.,The History of Civilisation of the people of-Assam to the twelfth Cen tury A.D.,Third Ed.,Guwahati,1987,ppe244-45. (b) Barua, K. L. ,·Early History of :Kama r;upa, Second Ed.,Guwahati, 1966, p.127 2. Ibid. p. 135. 3. l3asu, U.K.,Assam in the l\hom J:... ge, Calcutta, 1 1970, p.12. ··,· ·..... ·. '.' ' ,- l '' '.· 2 Kingdom., Ahom Kingdom., J:ayantiya kingdom and the chutiya kingdom. TheAhom, Kachari and Jayantiya kingdoms continued to exist till ' ' the British annexation: but the kingdoms of Kamata and Chutiya came to decay by- the turn of the sixteenth century~ · . -

International Journal of History & Scientific Approach

International Journal of History & Scientific Approach History and Culture: A Study on the Importance of the Place Names of Chandrapur Rosie Patangia Assistant Professor and Head, Deptt of English, Narangi Anchalik Mahavidyalaya, Narengi, Guwahati-171, Dist: Kamrup (Metro), Assam, India & Ph.D Research Scholar, Folklore Department, Gauhati University, Guwahati- 781014, Assam, India Abstract: History has its culture. Every place is denoted by a name. Each place name carries its own culture and tradition. The memory of a place is deeply embedded in its history, historical characters, legendary heroes, historical events etc. Assam in general and Kamrup in particular is rich in its culture and history. The place names speak of the past history of that place and helps in building identity. In Assam, we find innumerable places connected with oral narratives, folk beliefs, culture, history, myths, and legends. The present paper is an attempt to study the place names of Chandrapur and its cultural and historical significance. Key words: History, Culture, Place, Names, Chandrapur, historical significant. Introduction Every place from the macrocosm to the microcosm embodies its community, history and culture. Robert Murphy (1986) highlights that “Culture means the total body of tradition borne by a society and transmitted from generation to generation.” The Oxford English Dictionary (2007) defines a ‘place’ as a ‘particular position or area or a portion of space occupied by or set aside for someone or something’. It defines a ‘name’ as ‘a word or words by which someone or something is known.”Each place has its own cultural and historical background. While the term ‘cultural’ refers to the ideas, customs and social behavior of a society, the word ‘historical’ relates to past events or history. -

1. the Ahom Dynasty Ruled the Ahom Kingdom for Approximately A) 300 Years B) 600 Years C) 500 Years D) 400 Years

Visit www.AssamGovJob.in for more GK and MCQs 1. The Ahom Dynasty ruled the Ahom Kingdom for approximately a) 300 Years b) 600 Years c) 500 Years d) 400 Years 2. Who was the founder of the Varmana Dynasty? (a) Bhaskar Varman (b) Pushyavarman (c) Mahendravarman (d) Banabhatta 3. In which year did the Koch King Naranarayan invade the Ahom kingdom? (a) 1555 (b) 1562 (c) 1665 (d) 1552 4. The Yandaboo Treaty was signed in 1826 between (a) British Crown and the Burmese (b) British King and the Ahom King (c) East India Company and the Ahom King (d) East India Company and the Burmese 5. Which Ahom king was known as ‘Dihingia Roja’ ? (a) Suhungmung (b) Sukapha (c) Suseupa (d) Sudangpha 6. Who was the last ruler of Ahom kingdom? (a) Sudingpha (b) Jaydwaja Singha (c) Jogeswar Singha (d) Purandar Singha 7. The Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang visited Kamarupa in which year? (a) 602 A.D. (b) 643 A.D. (c) 543 A.D. (d) 650 A.D. 8. Which among the following has written the Prahlada Charita? (a) Rudra Kandali (b) Madhav Kandali (c) Harivara Vipra (d) Hema Saraswati 9. Which Swargadeo shifted the capital of the Ahom Kingdom from Garhgaon to Rangpur (a) Gadhar Singha (b) Rudra Singha (c) Siva Singha (d) None of them 10. Borphukans were from the following community (a) Chutias (b) Mech (c) Ahoms (d) Kacharis 11. Who founded the Assam Association in 1903? (a) Manik Chandra Baruah (b) Jaggannath Baruah (c) Navin Chandra Bordoloi (d) None of them 12. Phulaguri uprising, first ever peasant movement in India that occurred in middle Assam in which year? (a) 1861 (b) 1857 (c) 1879 (d) 1836 13. -

Goalpariya Language a Brief Study

GOALPARIYA LANGUAGE A BRIEF STUDY By Dr. Mir Jahan Ali Prodhani M.A.(Triple), PGDTE(CIEFL), Ph.D. Asstt. Prof., Dept. of English B.N.College, Dhubri (Assam) NINAD GOSTI GAUHATI UNIVERSITY CAMPUS GUWAHATI-14 GOALPARIYA LANGUAGE : A BRIEF STUDY is a synchronic study by Dr. Mir Jahan Ali Prodhani based on his knowledge as a native speaker of the language and the information collected by him as the investigator of an MRP on Goalpariya Language: A Synchronic Study financed by the UGC during the financial year 2009-10. Published by NINAD GOSTI GAUHATI UNIVERSITY CAMPUS GUWAHATI-14 © The author Price: Rs. 50.00 First Edition: July, 2010 DECLARATION This is to declare that this book represents my own original work, except for the materials gathered from scholarly writings and guidance required from the experts, retired teachers, parents and all other sources, acknowledged appropriately in the book. In connection with the phonetic transcription, I further declare that I have followed the system adopted by “THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY” rather than the I.P.A. in order to avoid certain inconveniences. - The Writer ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I sincerely acknowledge the help and guidance of Dr. K. G. Vijayakrishnan, Head of the Department of Linguistics & Contemporary English, CIEFL, Hyderabad-7, Dr. Dilip Borah, Reader, Department of M.I.L., G.U. and Sri G. S. Pande, Ex- Principal of P. B. College, Gauripur in writing this book. I also acknowledge the help and co-operation of all the lecturers in the Department of English of B. N. college, Dhubri without which it would have not been possible for me to collect the huge amount of data and information required for this book. -

The Serpent Power by Woodroffe Illustrations, Tables, Highlights and Images by Veeraswamy Krishnaraj

The Serpent Power by Woodroffe Illustrations, Tables, Highlights and Images by Veeraswamy Krishnaraj This PDF file contains the complete book of the Serpent Power as listed below. 1) THE SIX CENTRES AND THE SERPENT POWER By WOODROFFE. 2) Ṣaṭ-Cakra-Nirūpaṇa, Six-Cakra Investigation: Description of and Investigation into the Six Bodily Centers by Tantrik Purnananda-Svami (1526 CE). 3) THE FIVEFOLD FOOTSTOOL (PĀDUKĀ-PAÑCAKA THE SIX CENTRES AND THE SERPENT POWER See the diagram in the next page. INTRODUCTION PAGE 1 THE two Sanskrit works here translated---Ṣat-cakra-nirūpaṇa (" Description of the Six Centres, or Cakras") and Pādukāpañcaka (" Fivefold footstool ")-deal with a particular form of Tantrik Yoga named Kuṇḍalinī -Yoga or, as some works call it, Bhūta-śuddhi, These names refer to the Kuṇḍalinī-Śakti, or Supreme Power in the human body by the arousing of which the Yoga is achieved, and to the purification of the Elements of the body (Bhūta-śuddhi) which takes place upon that event. This Yoga is effected by a process technically known as Ṣat-cakra-bheda, or piercing of the Six Centres or Regions (Cakra) or Lotuses (Padma) of the body (which the work describes) by the agency of Kuṇḍalinī- Sakti, which, in order to give it an English name, I have here called the Serpent Power.1 Kuṇḍala means coiled. The power is the Goddess (Devī) Kuṇḍalinī, or that which is coiled; for Her form is that of a coiled and sleeping serpent in the lowest bodily centre, at the base of the spinal column, until by the means described She is aroused in that Yoga which is named after Her. -

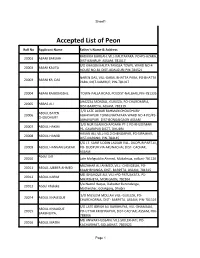

Accepted List of Peon

Sheet1 Accepted List of Peon Roll No Applicant Name Father's Name & Address RADHIKA BARUAH, VILL-KALITAPARA. PO+PS-AZARA, 20001 ABANI BARUAH DIST-KAMRUP, ASSAM, 781017 S/O KHAGEN KALITA TANGLA TOWN, WARD NO-4 20002 ABANI KALITA HOUSE NO-81 DIST-UDALGURI PIN-784521 NAREN DAS, VILL-GARAL BHATTA PARA, PO-BHATTA 20003 ABANI KR. DAS PARA, DIST-KAMRUP, PIN-781017 20004 ABANI RAJBONGSHI, TOWN-PALLA ROAD, PO/DIST-NALBARI, PIN-781335 AHAZZAL MONDAL, GUILEZA, PO-CHARCHARIA, 20005 ABBAS ALI DIST-BARPETA, ASSAM, 781319 S/O LATE AJIBAR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY ABDUL BATEN 20006 ABHAYAPURI TOWN,NAYAPARA WARD NO-4 PO/PS- CHOUDHURY ABHAYAPURI DIST-BONGAIGAON ASSAM S/O NUR ISLAM CHAPGARH PT-1 PO-KHUDIMARI 20007 ABDUL HAKIM PS- GAURIPUR DISTT- DHUBRI HASAN ALI, VILL-NO.2 CHENGAPAR, PO-SIPAJHAR, 20008 ABDUL HAMID DIST-DARANG, PIN-784145 S/O LT. SARIF UDDIN LASKAR VILL- DUDPUR PART-III, 20009 ABDUL HANNAN LASKAR PO- DUDPUR VIA ARUNACHAL DIST- CACHAR, ASSAM Abdul Jalil 20010 Late Mafiguddin Ahmed, Mukalmua, nalbari-781126 MUZAHAR ALI AHMED, VILL- CHENGELIA, PO- 20011 ABDUL JUBBER AHMED KALAHBHANGA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, 781315 MD ISHAHQUE ALI, VILL+PO-PATUAKATA, PS- 20012 ABDUL KARIM MIKIRBHETA, MORIGAON, 782104 S/o Nazrul Haque, Dabotter Barundanga, 20013 Abdul Khaleke Motherjhar, Golakgonj, Dhubri S/O MUSLEM MOLLAH VILL- GUILEZA, PO- 20014 ABDUL KHALEQUE CHARCHORRIA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, PIN-781319 S/O LATE IDRISH ALI BARBHUIYA, VILL-DHAMALIA, ABDUL KHALIQUE 20015 PO-UTTAR KRISHNAPUR, DIST-CACHAR, ASSAM, PIN- BARBHUIYA, 788006 MD ANWAR HUSSAIN, VILL-SIOLEKHATI, PO- 20016 ABDUL MATIN KACHARIHAT, GOLAGHAT, 7865621 Page 1 Sheet1 KASHEM ULLA, VILL-SINDURAI PART II, PO-BELGURI, 20017 ABDUL MONNAF ALI PS-GOLAKGANJ, DIST-DHUBRI, 783334 S/O LATE ABDUL WAHAB VILL-BHATIPARA 20018 ABDUL MOZID PO&PS&DIST-GOALPARA ASSAM PIN-783101 ABDUL ROUF,VILL-GANDHINAGAR, PO+DIST- 20019 ABDUL RAHIZ BARPETA, 781301 Late Fizur Rahman Choudhury, vill- badripur, PO- 20020 Abdul Rashid choudhary Badripur, Pin-788009, Dist- Silchar MD. -

Gazetteer of India Tirap District

Gazetteer of India ARUNACHAL PRADESH Tirap District GAZETTEER OF INDIA ARUNACHAL PRADESH TIRAP DISTRICT ARUNACHAL PRADESH DISTRICT GAZETTEERS TIRAP DISTRICT Edited by S. DUTTA CHOUDHURY GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1980 Published by Shri R.N. Bagchi Director of Information and Public Relations Government of Arunachal Pradesh, Shillong Printed by N.K, Gossain & Co. Private Ltd. 13/7ArifFRoad Calcutta 700 067 © Government of Arunachal Pradesh First Edition: 1980 First Reprint Edition: 2008 ISBN--978-81-906587-1-3 Price: Rs. 225/- Reprinted by M/s Himalayan Publishers Legi Shopping Con^jlex, BankTinali,ltanagar-791 111. FOREWORD I am happy to know that the Tirap District Gazetteer is soon coming out. This will be the second volume of District Gazetteers of Arunachal Pradesh — the first one on Lohit District was published during last year. The Gazetteer presents a comprehensive view of the life in Tirap District. The narrative covers a wide range of subjects and contains a wealth of information relating to the life style of the people, the geography of the area and also developments made so far in various sectors. The Tirap District Gazetteer, 1 hope, would serve a very useful purpose as a reference book. Raj Niwas R. N. Haldipur ltanagar-791111 Lieutenant Governor, Arunachal Pradesh May 6. 1980 PREFACE The present volume is the second in the series of Arunachal Pradesh District Gazetteers. The publication of this volume is the work of the Gazetteers Department of the Government of Arunachal Pradesh, carried out persistently over a number of years. In fact, the draft of Tirap District Gazetteer passed through a long course of examinations, changes and rewriting until the revised draft recommended by the Advisory Board in 1977 was approved by the Government of Arunachal Pradesh in 1978 and finally by the Government of India in 1979. -

CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY of the REGION Ahom

CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY OF THE REGION Ahom and Assam are inter-related terms. The word Ahom means the SHAN or the TAI people who migrated to the Brahma putra valley in the 13th Century A.D. from their original homeland MUNGMAN or PONG situated in upper Bunna on the Irrawaddy river. The word Assam refers to the Brahmaputra valley and the adjoining areas where the Shan people settled down and formed a kingdom with the intention of permanently absorbing in the land and its heritage. From the prehistoric period to about 13th/l4 Century A.D. Assam was referred to as Kamarupa and Pragjyotisha in Indian literary works and historical accounts. Early Period ; Area and Jurisdiction In the Ramayana and Mahabharata and in the Puranik and Tantrik literature, there are numerous references to ancient Assam, which was known as Pragjyotisha in the epics and Kamarupa in the Puranas and Tantras. V^Tien the stories related to it inserted in the Maha bharata, it stretched southward as far as the Bay of Bengal and its western boundary was river Karotoya. This was then a river of the first order and united in its bed the streams which now form the Tista, the Kosi and the Mahanada.^ 14 15 According to the most of the Puranas dealing with geo graphy of the earlier period, the kingdom extended upto the river Karatoya in the west and included Manipur, Jayantia, Cachar, parts of Mymensing, Sylhet, Rangpur and portions of 2 Bhutan and Nepal. The Yogini Yantra (V I:16-18) describes the boundary as - Nepalasya Kancanadrin Bramaputrasye Samagamam Karotoyam Samarabhya Yavad Dipparavasinara Uttarasyam Kanjagirah Karatoyatu pascime tirtharestha Diksunadi Purvasyam giri Kanyake Daksine Brahmaputrasya Laksayan Samgamavadhih Kamarupa iti Khyatah Sarva Sastresu niscitah.