Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bicentennial Journey

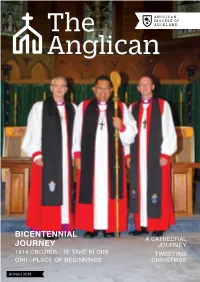

BICENTENNIAL A CATHEDRAL JOURNEY JOURNEY 1914 CROZIER - TE TAKE KI OIHI TWEETING OIHI - PLACE OF BEGINNINGS CHRISTMAS Advent 2014 1 BISHOP’S MESSAGE Find the Bishops on Facebook: Bishop Ross Bay / Bishop Jim White his year’s meeting of the Synod was a very special number of other places where there are Anglican communities occasion with many people able to make their pilgrimage and ministry. The purpose of the visit was to strengthen Tto Oihi and Marsden Cross for the first time. Our part the relationship between Auckland and Melanesia that has in God’s mission was a significant theme woven through the existed since the time that Selwyn and Patteson established Synod. Being present in the “cradle of Christianity” in Aotearoa the Melanesian Mission. We hope for ongoing contact and a brought a fresh focus to this call on our lives as Christian deepening of our relationship in the years ahead. Peter and disciples. Very soon we will celebrate the bicentenary of those Kahu Bargh have recently returned from a semester teaching at beginnings with the powhiri and opening of Rangihoua Heritage Bishop Patteson Theological College. Next year marks the 40th Park and culminating in this year’s Christmas Day’s service at anniversary of the Church in Melanesia becoming a Province Marsden Cross. within the Anglican Communion. Part of our build up to that was the joint service with Tai I wish you every blessing for Advent and Christmas in this Tokerau at Holy Sepulchre Church on Aotearoa Sunday. Gospel bicentenary year in Aotearoa. Following the powhiri, we gifted the centenary crozier to Bishop Kito. -

The Church Militant: Dunedin Churches and Society During World War One

The Church Militant: Dunedin Churches and Society During World War One Dickon John Milnes A thesis submitted to the University of Otago in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 31 January 2015 Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................. vii List of Tables .................................................................................................................. vii Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. vii Naming Conventions .................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................... ix Abstract ............................................................................................................................ xi Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Why Dunedin? .................................................................................................................................... 1 War-time Dunedin ............................................................................................................................. 1 Religious History in New Zealand .................................................................................................. -

Thesis Fulltext.Pdf (2.129Mb)

Collegiate Debating Societies in New Zealand: The Role of Discourse in an Inter-Colonial Setting, 1878-1902 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury, New Zealand by Bettina Kaiser University of Canterbury 2008 Submission date 30 April 2008 Dissertation Length 80,000 words Copyright © 2008 by Bettina Kaiser All rights reserved To Brunhild, Andrea und Peter Kaiser, Elisabet Pehl and Francis Zinke. Man is ‘the heir of all the ages’; he cannot divest himself of his patrimony and begin the world again. John Macmillan Brown, 1881, 13 Abstract Collegiate Debating Societies in New Zealand: The Role of Discourse in an Inter-Colonial Setting, 1878-1902 By Bettina Kaiser This thesis examines how, in New Zealand during the nineteenth century, debate was practised as an educative means to cultivate a standard of civic participation among settlers. Three collegiate debating societies and their activities between 1878 and 1902 are the object of this study. The discussion of these three New Zealand societies yields a distinctly colonial concept of debate. In the New Zealand public forum, a predominantly Pakeha intellectual elite put forth the position that public decisions should be determined by a process of deliberation that was conducted by educated individuals. This project was dominated by scientific argumentation that underpinned debate as a reliable means of discursive interaction. New Zealand’s intellectual elite was influenced by similar trends in Britain and the United States. Moreover, the concept of debate, that developed over the period of thirty years, carried significant normative connotations that rendered rational argumentation an acceptable form of discursive interaction. -

Sentimental Equipment‟: New Zealand, the Great War and Cultural Mobilisation

„Sentimental Equipment‟: New Zealand, the Great War and Cultural Mobilisation By Steven Loveridge A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Victoria University of Wellington 2013 ‗See that little stream - we could walk to it in two minutes. It took the British a month to walk to it - a whole empire walking very slowly, dying in front and pushing forward behind. And another empire walked very slowly backward a few inches a day, leaving the dead like a million bloody rugs … This western-front business couldn‘t be done again, not for a long time … This took religion and years of plenty and tremendous sureties and the exact relation that existed between the classes. …You had to have a whole-souled sentimental equipment [emphasis added] going back further than you could remember… This kind of battle was invented by Lewis Carroll and Jules Verne and whoever wrote Undine, and country deacons bowling and marraines in Marseilles and girls seduced in the back lanes of Wurtemburg and Westphalia. Why, this was a love battle - there was a century of middle-class love spent here … All my beautiful lovely safe world blew itself up here with a great gust of high explosive love‘.1 1 F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tender is the Night (London, 1985), pp.67-68. ii Abstract During the First World War, New Zealand society was dominated by messages stressing the paramount importance of the war effort to which the country was so heavily committed. -

United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT UNITED SOCIETY FOR THE PROPAGATION OF THE GOSPEL Records, 1718-1952 Reels M1201-1335, M1401-1516 United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel 15 Tufton Street London SW1 National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1951, 1977-79 CONTENTS Page 4 Historical note Reels M1201-1335 6 Anniversary sermons and annual reports, 1901-35 8 Journals, 1901-35 8 Minutes of Standing Committee, 1778-1819, 1902-35 11 Letters and documents arranged geographically, 1789-1924 (C MSS) 15 Letters and papers received from abroad, 1850-1935 (D MSS) 34 Missionary reports, 1856-1938 (E MSS) 54 Copies of letters sent, 1844-1935 57 Copies of letters received, 1834-1928 (CLR MSS) 63 Miscellaneous manuscripts, 1839-1937 (X MSS) 82 Fulham papers, 1817-26 83 Candidates’ testimonials, 1821-1930 105 Personal papers, 1910-70 107 Secretary’s letters, 1898-1924 108 Women’s work, 1868-1933 117 Unlisted material, 1795-1935 137 Miscellaneous papers, 1848-1950 Reels M1401-1516 139 Minutes of Standing Committee, 1833-1901 143 Annual reports, 1719-1900 145 Letters and papers received from abroad, 1857-1900 (D MSS) 147 Letters and documents arranged geographically, 1789-1859 (C MSS) 150 Reports from missionaries, 1845-1900 (E MSS) 153 Copies of letters sent, 1837-1900 153 Miscellaneous manuscripts, 1788-1813 (X MSS) 2 154 Letters and papers received from abroad, 1850-59 (D MSS) 155 Journals, 1783-1901 158 Miscellaneous papers, 1854 Explanatory note M1401-1516 were originally filmed by the Library of Congress in 1951 and copies were subsequently acquired by the National Library of Australia and the State Library of New South Wales.