The Virginia Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of the Western Rite Vicariate

A Short History of the Western Rite Vicariate Benjamin Joseph Andersen, B.Phil, M.Div. HE Western Rite Vicariate of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America was founded in 1958 by Metropolitan Antony Bashir (1896–1966) with the Right Reverend Alex- T ander Turner (1906–1971), and the Very Reverend Paul W. S. Schneirla. The Western Rite Vicariate (WRV) oversees parishes and missions within the Archdiocese that worship according to traditional West- ern Christian liturgical forms, derived either from the Latin-speaking Churches of the first millenium, or from certain later (post-schismatic) usages which are not contrary to the Orthodox Faith. The purpose of the WRV, as originally conceived in 1958, is threefold. First, the WRV serves an ecumeni- cal purpose. The ideal of true ecumenism, according to an Orthodox understanding, promotes “all efforts for the reunion of Christendom, without departing from the ancient foundation of our One Orthodox Church.”1 Second, the WRV serves a missionary and evangelistic purpose. There are a great many non-Orthodox Christians who are “attracted by our Orthodox Faith, but could not find a congenial home in the spiritual world of Eastern Christendom.”2 Third, the WRV exists to be witness to Orthodox Christians themselves to the universality of the Or- thodox Catholic Faith – a Faith which is not narrowly Byzantine, Hellenistic, or Slavic (as is sometimes assumed by non-Orthodox and Orthodox alike) but is the fulness of the Gospel of Jesus Christ for all men, in all places, at all times. In the words of Father Paul Schneirla, “the Western Rite restores the nor- mal cultural balance in the Church. -

Worldwide Communion: Episcopal and Anglican Lesson # 23 of 27

Worldwide Communion: Episcopal and Anglican Lesson # 23 of 27 Scripture/Memory Verse [Be] eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace: There is one body and one Spirit just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call; one Lord, one Faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all. Ephesians 4: 3 – 6 Lesson Goals & Objectives Goal: The students will gain an understanding and appreciation for the fact that we belong to a church that is larger than our own parish: we are part of The Episcopal Church (in America) which is also part of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Objectives: The students will become familiar with the meanings of the terms, Episcopal, Anglican, Communion (as referring to the larger church), ethos, standing committee, presiding bishop and general convention. The students will understand the meaning of the “Four Instruments of Unity:” The Archbishop of Canterbury; the Meeting of Primates; the Lambeth Conference of Bishops; and, the Anglican Consultative Council. The students will encounter the various levels of structure and governance in which we live as Episcopalians and Anglicans. The students will learn of and appreciate an outline of our history in the context of Anglicanism. The students will see themselves as part of a worldwide communion of fellowship and mission as Christians together with others from throughout the globe. The students will read and discuss the “Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral” (BCP pages 876 – 877) in order to appreciate the essentials of an Anglican identity. Introduction & Teacher Background This lesson can be as exciting to the students as you are willing to make it. -

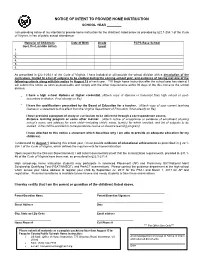

Notice of Intent to Provide Home Instruction Form

NOTICE OF INTENT TO PROVIDE HOME INSTRUCTION SCHOOL YEAR ________ I am providing notice of my intention to provide home instruction for the child(ren) listed below as provided by §22.1-254.1 of the Code of Virginia, in lieu of public school attendance: Name(s) of Child(ren) Date of Birth Grade FCPS Base School (last, first, middle initial) Level 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. As prescribed in §22.1-254.1 of the Code of Virginia, I have included or will provide the school division with a description of the curriculum, limited to a list of subjects to be studied during the coming school year, and evidence of having met one of the following criteria along with this notice by August 15 of each year. **If I begin home instruction after the school year has started, I will submit this notice as soon as practicable and comply with the other requirements within 30 days of the this notice to the school division. I have a high school diploma or higher credential. (Attach copy of diploma or transcript from high school or post- secondary institution, if not already on file) I have the qualifications prescribed by the Board of Education for a teacher. (Attach copy of your current teaching license or a statement to this effect from the Virginia Department of Education, if not already on file) I have provided a program of study or curriculum to be delivered through a correspondence course, distance learning program or some other manner. (Attach notice of acceptance or evidence of enrollment showing school’s name and address for each child—including child’s name, term(s) for which enrolled, and list of subjects to be studied if the child is enrolled in correspondence course or distance learning program). -

Progress Report

PROGRESS REPORT Donald L. Plusquellic, Mayor YEAREND 2003 CAPITAL INVESTMENT & COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Published May 7, 2004 Compiled by Department of Planning & Urban Development Department of Finance Bureau of Engineering 2003 CAPITAL INVESTMENT AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM TABLE OF CONTENTS PROJECT PAGE PROJECT PAGE TRANSPORTATION 1 Bridge Maintenance 10 Broadway Street Viaduct 11 Arterials/Collectors 1 Carnegie Ave. Bridge over Nesmith Lake Outlet 11 High Street Viaduct 11 Arterial Closeouts 1 Triplett Blvd. Bridge over Springfield Lake Outlet 12 Canton Road Signalization 1 Cuyahoga Street, Phase II 2 CD Public Improvements 12 Cuyahoga Street/Alberti Court 2 Darrow Road 2 Bisson NDA: Bellevue Avenue, et al 12 East Exchange Street/Arc Street Signalization 3 Campbell Street 13 East Market Street Signalization Upgrade 3 CD Area Closeouts 13 East Market Street Widening 3 Future CD Public Improvements 14 Euclid/Rhodes Avenue 4 Chandler Avenue, et al 14 Hickory Street 4 Idaho Street, et al 15 Howard/Ridge/High Streets 4 Kenmore Boulevard 15 Manchester Road 5 Oregon Avenue, et al 15 Newdale Avenue Extension 5 Honodle Avenue, et al 16 North Portage Path 5 Riverview Road Emergency Repairs 6 Concrete Street Repair 16 Sand Run Road 6 Sand Run Road Slope Stabilization 6 Concrete Street Repair Closeouts 16 South Arlington Street Signalization & Resurfacing 7 Hilbish Avenue 17 South Hawkins Avenue 7 South Main Street Widening 8 Expressways 17 Street Lighting Capital Replacement 8 Tallmadge Avenue Signalization 8 Expressway Ramp Repairs 17 Tallmadge Avenue Widening 9 Highway Landscaping 17 West Market Street 9 I-77 Widening 18 Innerbelt Study 18 Bridges 10 North Expressway Upgrade 18 U.S. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

THE JOURNAL of the ASSOCIATION of ANGLICAN MUSICIANS

THE JOURNAL of the ASSOCIATION OF ANGLICAN MUSICIANS AAM: SERVING THE EPSICOPAL CHURCH REPRINTED FROM VOLUME 29, NUMBER 3 (MARCH 2020) BY PERMISSION. Lambeth Conference Worship and Music: The Movement Toward Global Hymnody (Part I) MARTY WHEELER BURNETT, D.MIN. Since 1867, bishops in the Anglican Communion have A tradition of daily conference worship also developed, gathered periodically at the invitation of the Archbishop including morning Eucharist and Evening Prayer. During the of Canterbury. These meetings, known as Lambeth 1958 Lambeth Conference, The Church Times reported that: Conferences, have occurred approximately every ten years The Holy Communion will be celebrated each morning with the exception of wartime. A study of worship at the at 8:00 a.m. and Evensong said at 7:00 p.m. for those Lambeth Conferences provides the equivalent of “time-lapse staying in the house [Lambeth Palace]. In addition to photography”—a series of historical snapshots representative these daily services, once a week there will be a choral of the wider church over time. As a result, these decennial Evensong sung by the choirs provided by the Royal conferences provide interesting data on the changes in music School of Church Music, whose director, Mr. Gerald and liturgy throughout modern church history. Knight, is honorary organist to Lambeth Chapel. In 2008, I was privileged to attend the Lambeth The 1968 Lambeth Conference was the first and only Conference at the University of Kent, Canterbury, from July conference to offer an outdoor Eucharist in White City 16 through August 3. As a bishop’s spouse at the time, I was Stadium, located on the outskirts of London, at which 15,000 invited to participate in the parallel Spouses Conference. -

To Pray Again As a Catholic: the Renewal of Catholicism in Western Ukraine

To Pray Again as a Catholic: The Renewal of Catholicism in Western Ukraine Stella Hryniuk History and Ukrainian Studies University of Manitoba October 1991 Working Paper 92-5 © 1997 by the Center for Austrian Studies. Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from the Center for Austrian Studies. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the US Copyright Act of 1976. The the Center for Austrian Studies permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of the Center's Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses: teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce Center for Austrian Studies Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center. The origins of the Ukrainian Catholic Church lie in the time when much of present-day Ukraine formed part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was then, in 1596, that for a variety of reasons, many of the Orthodox bishops of the region decided to accept communion with Rome.(1) After almost four hundred years the resulting Union of Brest remains a contentious subject.(2) The new "Uniate" Church formally recognized the Pope as Head of the Church, but maintained its traditional Byzantine or eastern rite, calendar, its right to ordain married men as priests, and its right to elect its own bishops. -

Written Testimony to the Ohio Senate Finance Committee May 13, 2021

Written Testimony to the Ohio Senate Finance Committee May 13, 2021 Testimony from Kristin Warzocha, President and CEO, Greater Cleveland Food Bank and Board Chair, Ohio Association of Foodbanks Good afternoon Chairman Dolan, Vice Chair Gavarone, Ranking Member Sykes, and members of the Senate Finance Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to submit testimony on behalf of the Ohio Association of Foodbanks budget request regarding Amended Substitute House Bill 110. I am Kristin Warzocha, President and CEO at the Greater Cleveland Food Bank. I am also honored to serve as Board Chair for the Ohio Association of Foodbanks. At the Greater Cleveland Food Bank, we work to ensure that everyone in our communities has the nutritious food they need every day. Last year we made possible fifty-five million meals in Ashland, Ashtabula, Cuyahoga, Geauga, Lake, and Richland Counties. This is not an isolated effort- instead, we partner with more than one thousand food pantries, hot meal programs, libraries, churches, schools, senior centers, and other nonprofits to get food out to those in need. This emergency hunger relief is done in partnership with the eleven other food banks throughout our state, collectively making up the Ohio Association of Foodbanks. Thank you for your longstanding support of the Ohio Food Program and the Ohio Agricultural Clearance Program. These two programs are critical to the health and wellbeing of food-insecure families who lack access to enough food for an active, healthy lifestyle. The need was already high in the Greater Cleveland area before the pandemic began. In 2019, Cleveland had the highest child poverty rate among the fifty largest U.S. -

The Commitment to Indigenous Self-Determination in the Anglican Church of Canada, 1967–2020

The Elusive Goal: The Commitment to Indigenous Self-Determination in the Anglican Church of Canada, 1967–2020 ALAN L. HAYES In1967 the Anglican Church of Canada (ACC) committed itself to support Indigenous peoples whowere callingonthe Cana- dian governmenttorecognize theirright to self-determination, andin1995 it resolved to move to recognizeIndigenous self- determination within thechurch itself. Nevertheless,inthe ACC, as in the countryatlarge, Indigenousself-determination hasremained an elusivegoal. To saysoisnot to deny theprogress that theACC has made in developingIndigenous leadership, governance, ministry, and advocacy. But with afew partial excep- tions, IndigenousAnglicansremain under the oversight of aset- tler-dominated churchwith its Eurocentric constitution, canons, policies, budgets, liturgical norms, assumptions, andadmin- istrativeprocedures.1 Whyhas the goalofIndigenous self- determinationprovensoelusive? Iintend to argue herethat colonialassumptions andstructures haveproven tenacious,and that, although Indigenous self-determination is consistent with historical patternsofChristian mission andorganization, the 1 The terms‘‘settler’’and ‘‘Indigenous’’are both problematic, but the nature of this discussion requires,atleast provisionally,abinaryterminology,and these terms are currently widelyused. The Rev.Canon Dr.AlanL.Hayes is BishopsFrederickand Heber Wilkinson Professor of the historyofChristianity at Wycliffe College and the Toronto SchoolofTheology at theUniversity of Toronto. Anglicanand EpiscopalHistory Volume 89, -

Church of North India Synodical Board of Social Services Employees’ Service Rules

CHURCH OF NORTH INDIA SYNODICAL BOARD OF SOCIAL SERVICES EMPLOYEES’ SERVICE RULES CNI -SYNODICAL BOARD OF SOCIAL SERVICES 16 PANDIT PANT MARG NEW DELHI- 110001 FAX : 91-11-23712126 PHONE: 23718168/23351727 Towards Building Communities of www.cnisbss.org Resistance & Hope CHURCH OF NORTH INDIA SYNODICAL BOARD OF SOCIAL SERVICES EMPLOYEES’ SERVICE RULES I. PREFACE 1. These rules shall be called CNI-SBSS Employee’s Service Rules and shall be applicable to all the employees of the CNI- SBSS. 2. These rules shall supersede all or any previous rules or practices which have been in operation on matters covered by those rules. II. DEFFINITIONS 1. ‘Synodical Board’ means CNI Synodical Board of Social Services and includes all departments, offices, sub-centre, sections, Resource canters and branches where the activities of the Board are carried out. 2. ‘Governing Body’ means the Governing Body of the Synodical Board to whom, by the rules of the said Board, the management of its affairs shall be entrusted. 3. ‘Chief Functionary’ The Chief Coordinator is the Chief Functionary. 4. ‘Premises’ means the entire premises of the CNI-SBSS whether situated inside or outside the main institution premises. 5. ‘Habitual’ means commission or omission of an act for not less than three occasions in a Calendar month. 6. ‘Masculine’ shall include ‘Feminine’ and ‘Singular’ shall imply ‘Plural’ where relevant, and vice versa. 7. ‘Salary’ ’ means and includes all components i.e., in basic and all other allowances admissible while on duty. III. GENERAL 1. Every employee must attend Morning Worship Service at the Office held every day at the stipulated time during all working days. -

Evensong 9 August 2018 5:15 P.M

OUR VISION: A world where people experience God’s love and are made whole. OUR MISSION: To share the love of Jesus through compassion, inclusivity, creativity and learning. Evensong 9 August 2018 5:15 p.m. Evensong Thursday in the Eleventh Week after Pentecost • 9 August 2018 • 5:15 pm Welcome to Grace Cathedral. Choral Evensong marks the end of the working day and prepares for the approaching night. The roots of this service come out of ancient monastic traditions of Christian prayer. In this form, it was created by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury in the 16th century, as part of the simplification of services within the newly-reformed Church of England. The Episcopal Church, as part of the worldwide Anglican Communion, has inherited this pattern of evening prayer. In this service we are invited to reflect on the business of the past day, to pray for the world and for ourselves, and to commend all into God’s hands as words of Holy Scripture are said and sung. The beauty of the music is offered to help us set our lives in the light of eternity; the same light which dwelt among us in Jesus, and which now illuminates us by the Spirit. May this service be a blessing to you. Voluntary Canzonetta William Mathias The people stand as the procession enters. The Invitatory and Psalter Opening Sentence Said by the officiant. Preces John Rutter Officiant O Lord, open thou our lips. Choir And our mouth shall shew forth thy praise. O God, make speed to save us. -

THE CONFESSOR's AUTHORITY the Catholic Church Meets

CHAPTER THREE THE CONFESSOR'S AUTHORITY The Catholic Church meets people's need for authority and abso lution with its doctrine on the penance sacrament and its teaching that the priest possesses divine qualities to administer the sacrament and exercise moral authority. During the ceremony of ordination, God Himself has made a priest the instrument of His power in this world. Thus, the priest is endowed with a character indelebilis which distinguishes him from all secular persons and qualifies him to carry out his mission as intercessor between God and Man, indeed even to deputize for God among mortals. A Catholic writer has said that the priest shows his extraordinary qualities as director of souls by his "apostolic zeal, knowledge of God's ways and supernatural wisdom". 1 But those gifts are not enough for a priest when he officiates in the penance sacrament. They could have their effect also outside that sacrament. As administrator of the sacrament he possesses a special and divine instinct: this shows him the way when he instructs penitents on remedies for their sins and gives them guidance on their future conduct. 2 Such an image of the priest's high office is inculcated in Catholics by their creed itself. A good Catholic accepts a priest's authority; consequently he is prepared in advance to follow confessional advice and to comply in all matters with directions as to his way of life. 3 This maintenance of clerical authority has an integral place in the structure of Roman Catholic doctrine. It is connected there both with the concept of the Church as a whole and with teaching on the sacraments.