Phase-Out 2020: Monitoring Europe's Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

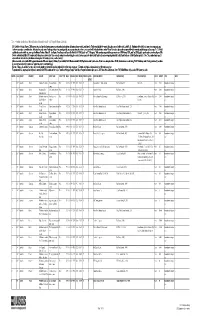

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

The Case for Mine Energy – Unlocking Deployment at Scale in the UK a Mine Energy White Paper

The Case for Mine Energy – unlocking deployment at scale in the UK A mine energy white paper @northeastlep northeastlep.co.uk @northeastlep northeastlep.co.uk Foreword At the heart of this Government’s agenda are three key priorities: the development of new and innovative sources of employment and economic growth, rapid decarbonisation of our society, and levelling up - reducing the inequalities between diferent parts of the UK. I’m therefore delighted to be able to ofer my support to this report, which, perhaps uniquely, involves an approach which has the potential to address all three of these priorities. Mine energy, the use of the geothermally heated water in abandoned coal mines, is not a new technology, but it is one with the potential to deliver thousands of jobs. One quarter of the UK’s homes and businesses are sited on former coalfields. The Coal Authority estimates that there is an estimated 2.2 GWh of heat available – enough to heat all of these homes and businesses, and drive economic growth in some of the most disadvantaged communities in our country. Indeed, this report demonstrates that if we only implement the 42 projects currently on the Coal Authority’s books, we will deliver almost 4,500 direct jobs and a further 9-11,000 in the supply chain, at the same time saving 90,000 tonnes of carbon. The report also identifies a number of issues which need to be addressed to take full advantage of this opportunity; with investment, intelligence, supply chain development, skills and technical support all needing attention. -

United Kingdom – Extensive Potential and a Positive Outlook by Paul Lusty, British Geological Survey Introduction in Relation

United Kingdom – extensive potential and a positive outlook By Paul Lusty, British Geological Survey Introduction In relation to its size the United Kingdom (UK) is remarkably well-endowed with mineral resources as a result of its complex geological history. Their extraction and use have played an important role in the development of the UK economy over many years and minerals are currently worked at some 2100 mine and quarry sites. Production is now largely confined to construction minerals, primarily aggregates, energy minerals and industrial minerals including salt, potash, kaolin and fluorspar, although renewed interest in metals is an important development in recent years. With surging global demand for minerals the UK is seen by explorers as an attractive location to develop projects. With low political risk and excellent infrastructure a survey conducted by Resources Stocks (2009) ranked the UK twelfth in a global assessment of countries’ risk profiles for resource sector investment. Northern Ireland is notable in terms of the extensive licence coverage for gold and base metal exploration and in having the UK’s only operational metalliferous mine. The most advanced projects elsewhere include the Hemerdon tin-tungsten deposit in Devon, the South Crofty tin deposit in Cornwall and the Cononish gold deposit in central Scotland. UK coal has seen a resurgence during the last three years driven largely by higher global prices, making it more competitive with imports. Coal is also viewed as having a key role in the future UK energy mix. This has led to greater investment in UK operations resulting in increased numbers of new opencast sites commencing production and more permit applications for further sites. -

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2012

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2012 Production team: Iain MacLeay Kevin Harris Anwar Annut and chapter authors A National Statistics publication London: TSO © Crown Copyright 2012 All rights reserved First published 2012 ISBN 9780115155284 Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics Enquiries about statistics in this publication should be made to the contact named at the end of the relevant chapter. Brief extracts from this publication may be reproduced provided that the source is fully acknowledged. General enquiries about the publication, and proposals for reproduction of larger extracts, should be addressed to Kevin Harris, at the address given in paragraph XXIX of the Introduction. The Department of Energy and Climate Change reserves the right to revise or discontinue the text or any table contained in this Digest without prior notice. About TSO's Standing Order Service The Standing Order Service, open to all TSO account holders, allows customers to automatically receive the publications they require in a specified subject area, thereby saving them the time, trouble and expense of placing individual orders, also without handling charges normally incurred when placing ad-hoc orders. Customers may choose from over 4,000 classifications arranged in 250 sub groups under 30 major subject areas. These classifications enable customers to choose from a wide variety of subjects, those publications that are of special interest to them. This is a particularly valuable service for the specialist library or research body. All publications will be dispatched immediately after publication date. Write to TSO, Standing Order Department, PO Box 29, St Crispins, Duke Street, Norwich, NR3 1GN, quoting reference 12.01.013. -

Department of Energy & Climate Change Short Guide

A Short Guide to the Department of Energy & Climate Change July 2015 Overview Decarbonisation Ensuring security Affordability Legacy issues of supply | About this guide This Short Guide summarises what the | Contact details Department of Energy & Climate Change does, how much it costs, recent and planned changes and what to look out for across its main business areas and services. If you would like to know more about the NAO’s work on the DECC, please contact: Michael Kell Director, DECC VfM and environmental sustainability [email protected] 020 7798 7675 If you are interested in the NAO’s work and support The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending for Parliament and is independent of government. The Comptroller and Auditor General for Parliament more widely, please contact: (C&AG), Sir Amyas Morse KCB, is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO, which employs some 810 people. The C&AG Adrian Jenner certifies the accounts of all government departments and many other Director of Parliamentary Relations public sector bodies. He has statutory authority to examine and report [email protected] to Parliament on whether departments and the bodies they fund have used their resources efficiently, effectively, and with economy. Our 020 7798 7461 studies evaluate the value for money of public spending, nationally and locally. Our recommendations and reports on good practice For full iPad interactivity, please view this PDF help government improve public services, and our work led to Interactive in iBooks or GoodReader audited savings of £1.15 billion in 2014. -

Nuclear Decommissioning Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2006

Annual Report & Accounts 2006/7 Our mission is to: Deliver safe, sustainable and publicly acceptable solutions to the challenge of nuclear clean-up and waste management. This means never compromising on safety or security, taking full account of our social and environmental responsibilities, always seeking value for money for the taxpayer and actively engaging with stakeholders. 02 NDA Report and Accounts 2006/7 Welcome to the NDA Annual Report & Accounts 2006/7 Presented to Parliament pursuant sections 14 [6], [8] and 26 [10], [11] of the Energy Act 2004. Laid before the Houses of Parliament 9 October 2007 HC/1001. Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers 9 October 2007 SE/2007/171. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 9 October 2007. HC1001 London: The Stationery Office. 03 The Nuclear Decommissioning Authority 4 Contents 6 Our Priorities (NDA) is a non-departmental public 9 Chairman’s Report body set up under the Energy Act 2004. 11 Chief Executive’s Review This means that operationally we are 17 NDA Business Review 19 HSSE independent of Government, although 22 Decommissioning and Clean-up 24 Waste Management we report to the Secretary of State for 26 Commercial Operation Business, Enterprise and Regulatory 30 Nuclear Materials 32 Competition and Contracting Reform and to the Scottish Ministers. 36 Innovation, Skills, Research and Development R&D and Good Practice 42 Socio-Economic Support Our remit is to ensure that the and Stakeholder Engagement UK’s civil public sector nuclear sites 45 Operating Unit Reports 49 Site Licensee Reports for which we are responsible are 49 British Nuclear Group Sellafield Limited (BNGSL) decommissioned and cleaned up 57 Magnox Electric Limited 73 United Kingdom Atomic safely, securely, cost-effectively, Energy Authority (UKAEA) affordably and in ways that protect 83 Springfields Fuels Limited 86 NDA Owned Subsidiary Reports the environment for this and future 86 Direct Rail Services (DRS) 88 UK Nirex Limited generations. -

Länderprofil Großbritannien Stand: Juli / 2013

Länderprofil Großbritannien Stand: Juli / 2013 Impressum Herausgeber: Deutsche Energie-Agentur GmbH (dena) Regenerative Energien Chausseestraße 128a 10115 Berlin, Germany Telefon: + 49 (0)30 72 6165 - 600 Telefax: + 49 (0)30 72 6165 – 699 E-Mail: [email protected] [email protected] Internet: www.dena.de Die dena unterstützt im Rahmen der Exportinitiative Erneuerbare Energien des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Technologie (BMWi) deutsche Unternehmen der Erneuerbare-Energien-Branche bei der Auslandsmarkterschließung. Dieses Länderprofil liefert Informationen zur Energiesituation, zu energiepolitischen und wirtschaftlichen Rahmenbedingungen sowie Standort- und Geschäftsbedingungen für erneuerbare Energien im Überblick. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung, die nicht ausdrücklich vom Urheberrechtsgesetz zugelassen ist, bedarf der vorherigen Zustimmung der dena. Sämtliche Inhalte wurden mit größtmöglicher Sorgfalt und nach bestem Wissen erstellt. Die dena übernimmt keine Gewähr für die Aktualität, Richtigkeit, Vollständigkeit oder Qualität der bereitgestellten Informationen. Für Schäden materieller oder immaterieller Art, die durch Nutzen oder Nichtnutzung der dargebotenen Informationen unmittelbar oder mittelbar verursacht werden, haftet die dena nicht, sofern ihr nicht nachweislich vorsätzliches oder grob fahrlässiges Verschulden zur Last gelegt werden kann. Offizielle Websites www.renewables-made-in-germany.com www.exportinitiative.de Länderprofil Großbritannien – Informationen für -

The Coal Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2018-19

HC 2302 The Coal Authority Annual report and accounts 2018-19 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 60(6) of the Coal Industry Act 1994 and Accounts presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraph 15(4) of Schedule 1 to the Coal Industry Act 1994. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 27 June 2019. HC 2302 © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at The Coal Authority 200 Lichfield Lane Mansfield Nottinghamshire NG18 4RG Tel: 0345 762 6848 Email: [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-1424-5 CCS0419084554 06/19 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by APS on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Officers and professional advisors Chief Finance and Information Officer Auditors Paul Frammingham The Comptroller and Auditor General 200 Lichfield Lane National Audit Office Mansfield 157-197 Buckingham Palace Road Nottinghamshire Victoria NG18 4RG London SW1W 9SP Bankers Government Banking Services, Southern House, 7th Floor, Wellesley Grove, Croydon, CR9 1WW Performance report Overview 5 The work we do 6 Chair’s foreword -

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2020

DIGEST OF UNITED KINGDOM ENERGY STATISTICS 2020 This publication is available from: www.gov.uk/government/collections/digest-of-uk-energy- statistics-dukes If you need a version of this document in a more accessible format, please email [email protected]. Please tell us what format you need. It will help us if you say what assistive technology you use. This is a National Statistics publication The United Kingdom Statistics Authority has designated these statistics as National Statistics, in accordance with the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 and signifying compliance with the UK Statistics Authority: Code of Practice for Statistics. The continued designation of these statistics as National Statistics was confirmed in September 2018 following a compliance check by the Office for Statistics Regulation. The statistics last underwent a full assessment against the Code of Practice in June 2014. Designation can be broadly interpreted to mean that the statistics: • meet identified user needs • are well explained and readily accessible • are produced according to sound methods, and • are managed impartially and objectively in the public interest Once statistics have been designated as National Statistics it is a statutory requirement that the Code of Practice shall continue to be observed. © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. -

Flood Information

SAMPLE Issued by: The Coal Authority, Property Search Services, 200 Lichfield Lane, Berry Hill, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, NG18 4RG Website: www.groundstability.com Phone: 0345 762 6848 THE COAL AUTHORITY Our reference: 71003490624001 200 LICHFIELD LANE Your reference: MANSFIELD Date of your enquiry: 25 January 2019 NOTTINGHAMSHIRE Date we received your enquiry: 25 January 2019 NG18 4RG Date of issue: 25 January 2019 This report is for the property described in the address below and the attached plan. Non-Residential Enviro All-in-One - Off Coalfield This report is based on and limited to the records held by, the Coal Authority, at the time we answer the search. Coal mining No Information from the Coal Authority The property lies outside any defined coalfield area. Additional Remarks Information provided by the Coal Authority in this report is compiled in response to the Law Society's CON29M Coal Mining enquiries. The said enquiries are protected by copyright owned by the Law Society of 113 Chancery Lane, London WC2A 1PL. This report is prepared in accordance with the Law Society's Guidance Notes 2018, the User Guide 2018 and the Coal Authority's Terms and Conditions applicable at the time the report was produced. The Coal Authority owns the copyright in this report. The information we have used to write this report is protected by our database rights. All rights are reserved and unauthorised use is prohibited. If we provide a report for you, this does not mean that copyright and any other rights will pass SAMPLEto you. However, you can use the report for your own purposes. -

Nuclear Decommissioning Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2007/08

Nuclear Decommissioning Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2007/08 Annual Report & Accounts 2007/08 Nuclear Decommissioning Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2007/08 Our mission is to: Deliver safe, sustainable and publicly acceptable solutions to the challenge of nuclear clean-up and waste management. This means never compromising on safety or security, taking full account of our social and environmental responsibilities, always seeking value for money for the taxpayer and actively engaging with stakeholders. Nuclear Decommissioning Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2007/08 Welcome to the NDA Annual Report & Accounts 2007/08 Presented to Parliament pursuant sections 14 [6], [8] and 26 [10], [11] of the Energy Act 2004. Laid before the Houses of Parliament 17 July 2008 HC/827. Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers 17 July 2008 SG/2008/112. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 17 July 2008. HC827 London: The Stationery Office. £33.45 Nuclear Decommissioning Authority Annual Report and Accounts 2007/08 Contents 1 Foreword 2 Chairman’s Report 4 Chief Executive’s Review 11 HSSE 16 Financial Review 39 Directors and Executives 47 Directors’ Report 52 Corporate Governance 55 Remuneration Report Statement of the Directors’ and Accounting Officer 61 Responsibilities 62 Statement on Internal Control The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor 68 General to the Houses of Parliament 71 The Annual Accounts 71 Consolidated Income and Expenditure Account 71 Consolidated Statement of Recognised Gains -

The Australian Black Coal Industry

The Australian Black Coal Inquiry Report Industry Volume 2: Appendices Report No. 1 3 July 1998 A CONDUCT OF THE INQUIRY A.1 Introduction This appendix outlines the inquiry process and the organisations and individuals which have participated in the inquiry. Following receipt of the terms of reference on 9 July 1997, the Commission placed a notice in the national press inviting public participation in the inquiry and released an issues paper to assist participants in preparing their submissions. A list of those who made submissions is in Section A.2. The Commission also held informal discussions with organisations, companies and individuals to gain background information and to assist in setting an agenda for the inquiry. Organisations visited by the Commission are listed in Section A.3. In November 1997, the Commission held public hearings in Sydney and Brisbane. Following release of the draft report, the Commission held a second round of public hearings in May 1998. In total, 16 individuals and organisations gave evidence (see Section A.4). A transcript of the hearings was made publicly available. Mr Bill Scales, AO was Presiding Commissioner for this inquiry until 27 February 1998, when he resigned from the Commission. He was replaced as Presiding Commissioner by Mr John Cosgrove from that date. Mr Keith Horton-Stephens and Mr Nicholas Gruen were also Commissioners on the inquiry, but left the Commission prior to the completion of the final report. A.2 Submissions received Participant Submission No. ________________________________________________________________ ACB Consulting Services Pty Ltd 51 ARCO Coal Australia Inc. 21 Asia Pacific Strategy Pty Ltd 1, 38, 50, DR53 Association of Mine Related Councils DR57 A1 THE AUSTRALIAN BLACK COAL INDUSTRY Australian Coal Association 31 Australian Mines and Metals Association Inc.