FUNCTIONAL NEUROANATOMY in EQUINE BACK PAIN Goals: • To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Injury History in the Collegiate Equestrian Athlete: Part I: Mechanism of Injury, Demographic Data and Spinal Injury

Journal of Sports Medicine and Allied Health Sciences: Official Journal of the Ohio Athletic Trainers Association Volume 2 Issue 3 Article 3 January 2017 Injury History in the Collegiate Equestrian Athlete: Part I: Mechanism of Injury, Demographic Data and Spinal Injury Michael L. Pilato Monroe Community College, [email protected] Timothy Henry State University New York, [email protected] Drussila Malavase Equestrian Safety, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/jsmahs Part of the Biomechanics Commons, Exercise Science Commons, Motor Control Commons, Other Kinesiology Commons, Rehabilitation and Therapy Commons, Sports Medicine Commons, and the Sports Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pilato, Michael L.; Henry, Timothy; and Malavase, Drussila (2017) "Injury History in the Collegiate Equestrian Athlete: Part I: Mechanism of Injury, Demographic Data and Spinal Injury," Journal of Sports Medicine and Allied Health Sciences: Official Journal of the Ohiothletic A Trainers Association: Vol. 2 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25035/jsmahs.02.03.03 Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/jsmahs/vol2/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Sports Medicine and Allied Health Sciences: Official Journal of the Ohio Athletic Trainers Association by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Pilato, Henry, Malavase Collegiate Equine Injuries Pt. I JSMAHS 2017. 2(3). Article 3 Injury History in the Collegiate Equestrian Athlete: Part I: Mechanism of Injury, Demographic Data, and Spinal Injury Michael Pilato MS, ATC‡, Timothy Henry PhD, ATC€, Drussila Malavase Co-Chair ASTM F08.55 Equestrian Safety¥ Monroe Community College‡, State University New York; Brockport€, Equestrian Safety¥ Purpose: Equestrian sports are known to have a high risk and rate of injury. -

User's Manual

USER’S MANUAL The Bitless Bridle, Inc. email: [email protected] Phone: 719-576-4786 5220 Barrett Rd. Fax: 719-576-9119 Colorado Springs, Co. 80926 Toll free: 877-942-4277 IMPORTANT: Read the fitting instructions on pages four and five before using. Improper fitting can result in less effective control. AVOIDANCE OF ACCIDENTS Nevertheless, equitation is an inherently risky activity and The Bitless Bridle, Inc., can accept no responsibility for any accidents that might occur. CAUTION Observe the following during first time use: When first introduced to the Bitless Bridle™, it sometimes revives a horse’s spirits with a feeling of “free at last”. Such a display of exuberance will eventually pass, but be prepared for the possibility even though it occurs in less than 1% of horses. Begin in a covered school or a small paddock rather than an open area. Consider preliminary longeing or a short workout in the horse’s normal tack. These and other strategies familiar to horse people can be used to reduce the small risk of boisterous behavior. APPLICATION The action of this bridle differs fundamentally from all other bitless bridles (the hackamores, bosals, and sidepulls). By means of a simple but subtle system of two loops, one over the poll and one over the nose, the bridle embraces the whole of the head. It can be thought of as providing the rider with a benevolent headlock on the horse (See illustration below) . Unlike the bit method of control, the Bitless Bridle is compatible with the physiological needs of the horse at excercise. -

Clinical Assessment and Grading of Back Pain in Horses

J Vet Sci. 2020 Nov;21(6):e82 https://doi.org/10.4142/jvs.2020.21.e82 pISSN 1229-845X·eISSN 1976-555X Original Article Clinical assessment and grading of Internal Medicine back pain in horses Abubakar Musa Mayaki 1,2, Intan Shameha Abdul Razak 1,*, Noraniza Mohd Adzahan 3, Mazlina Mazlan 4, Abdullah Rasedee 5 1Department of Veterinary Preclinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia 2Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, P.M.B 2346, City Campus Complex, Sokoto, Nigeria 3Department of Farm and Exotic Animal Medicine and Surgery, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia 4Department of Veterinary Pathology and Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia 5Department of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosis, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Received: Mar 9, 2020 ABSTRACT Revised: Aug 23, 2020 Accepted: Aug 27, 2020 Background: The clinical presentation of horses with back pain (BP) vary considerably with *Corresponding author: most horse's willingness to take part in athletic or riding purpose becoming impossible. Intan Shameha Abdul Razak However, there are some clinical features that are directly responsible for the loss or failure of Department of Veterinary Preclinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra performance. Malaysia, 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia. Objectives: To investigate the clinical features of the thoracolumbar region associated with E-mail: [email protected] BP in horses and to use some of the clinical features to classify equine BP. Methods: Twenty-four horses comprised of 14 with BP and 10 apparently healthy horses © 2020 The Korean Society of Veterinary were assessed for clinical abnormality that best differentiate BP from normal horses. -

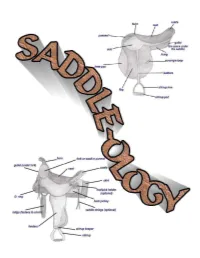

Saddleology (PDF)

This manual is intended for 4-H use and created for Maine 4-H members, leaders, extension agents and staff. COVER CREATED BY CATHY THOMAS PHOTOS OF SADDLES COURSTESY OF: www.horsesaddleshop.com & www.western-saddle-guide.com & www.libbys-tack.com & www.statelinetack.com & www.wikipedia.com & Cathy Thomas & Terry Swazey (permission given to alter photo for teaching purposes) REFERENCE LIST: Western Saddle Guide Dictionary of Equine Terms Verlane Desgrange Created by Cathy Thomas © Cathy Thomas 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................................................................................4 Saddle Parts - Western..................................................................5-7 Saddle Parts - English...................................................................8-9 Fitting a saddle........................................................................10-15 Fitting the rider...........................................................................15 Other considerations.....................................................................16 Saddle Types & Functions - Western...............................................17-20 Saddle Types & Functions - English.................................................21-23 Latigo Straps...............................................................................24 Latigo Knots................................................................................25 Cinch Buckle...............................................................................26 Buying the right size -

The Anatomy and Function of the Equine Thoracolumbar Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

Aus dem Veterinärwissenschaftlichen Department der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Lehrstuhl für Anatomie, Histologie und Embryologie Vorstand: Prof. Dr. Dr. Fred Sinowatz Arbeit angefertigt unter der Leitung von Dr. Renate Weller, PhD, MRCVS The Anatomy and Function of the equine thoracolumbar Longissimus dorsi muscle Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der tiermedizinischen Doktorwürde der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Vorgelegt von Christina Carla Annette von Scheven aus Düsseldorf München 2010 2 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Joachim Braun Berichterstatter: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Johann Maierl Korreferentin: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Bettina Wollanke Tag der Promotion: 24. Juli 2010 3 Für meine Familie 4 Table of Contents I. Introduction................................................................................................................ 8 II. Literature review...................................................................................................... 10 II.1 Macroscopic anatomy ............................................................................................. 10 II.1.1 Comparative evolution of the body axis ............................................................ 10 II.1.2 Axis of the equine body ..................................................................................... 12 II.1.2.1 Vertebral column of the horse.................................................................... -

Novel Dissection Approach of Equine Back Muscles

Published: November 19, 2018 RESEARCH ARTICLE Citation: Elbrønd V. et al. (2018). Novel dissection approach of equine back muscles: Novel dissection approach of equine back muscles: new advances in new advances in anatomy and topography - and anatomy and topography - and comparison to present literature. comparison to present literature. Science Publishing Group Journal Rikke Mark Schultz1, DVM, Vibeke Sødring Elbrønd2, DVM, Ph.D. 1(2). Author’s affiliations: Corresponding Author: 1. Equine Practice, Karlebovej 22, DK- 2980 Kokkedal. Vibeke Elbrønd Dept. of Animal and Veterinary 2. Dept. of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Vet. Faculty, SUND, Sciences, Vet. Faculty, SUND, KU, KU, Denmark Denmark E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Keywords: back muscles, Knowledge of the anatomy and topography of the equine back are topography, m. iliocostalis, m. essential for a correct diagnosis and treatment as well as longissimus dorsi, m. spinalis communication among therapists, especially since different authors have not always agreed upon the anatomical topography of the epaxial back muscles. In this study, we performed a novel 3-D dissection procedure that focused on maintaining the integrity of the myofascial role in muscle topography. A total of 17 horses were carefully dissected, recorded and videotaped. The results revealed some interesting points. 1) The iliocostalis muscle (IL) was found to be clearly distinct from the longissimus dorsi muscle (LD) and positioned ventral to the lateral edge of LD. 2) Two distinct variations in the origin of the IL, i) from the Bogorozky tendon and the ventral epimysium of m. longissimus dorsi (LD) at the caudo-lateral region at L1 to L5, and ii) from the lumbar myofascia lateral to the lumbar transverse processes at the level of L2 to L4 have been found. -

Riding a Lusitano at the Belgian Academy for the Art of Riding

Riding a Lusitano at the Belgian Academy for the Art of Riding Two years ago, I was able to establish contact with an equestrian academy from my home country, Belgium, and to visit them, observe them riding and training their horses, and take a lesson on one of their Lusitano schoolmasters. Back then, I just did basic movements (W/T/C, SI and some HP). That is probably all I was ready for at that time. This year, I came back, and after spending the last 2 ½ years focusing solely on my education - improving my equitation skills and my understanding of the correct principles of classical horse training, I was ready to do much more. The last few years have been a time of perseverance, sometimes seeming tedious, and I felt that I was kind off ‘missing out’ on the fun – like showing etc… However, this has more than paid off, and, this year things have really started to come together. For me, this opportunity to ride a more advanced schoolmaster has been the culmination of this year’s season, when all of it came together. I am now coming back with a totally renewed outlook on classical equitation. Thank you Jim for a superb job preparing me for this experience. I came to the school ready to go to serious work this time. Leopold Gombeer and Michel Barbieux are two professional riders/trainers who head the Academy and run a Lusitano breeding farm in Hoves, Belgium. Michel does most of the teaching, while Leopold works mostly on the horses. -

The Bedouin Bridle Rediscovered: a Welfare, Safety and Performance Enhancer by Fridtjof Hanson and Robert Cook

The Bedouin Bridle Rediscovered: A Welfare, Safety and Performance Enhancer by Fridtjof Hanson and Robert Cook “One of the troubles of our age is that habits of was the bridle that, for centu- ries, Bedouin horsemen had thought cannot change as quickly as techniques used in their tribal raids; a bridle with the result that as skill increases, wisdom they trusted with their lives. In fails.” – Bertrand Russell Lady Wentworth’s book, The Authentic Arabian Horse, the Part 1: Serendipity by Robert Cook author quotes what her mother, Lady Anne Blunt, had written in n 1985, during a working week in Kuwait, I was introduced to a 1879 about this “halter”: “The small group of tribesmen in the desert who had with them one Bedouin never uses a bit or bri- Ihorse. Without explanation, they asked me to examine their dle of any sort except for war, head-shy horse’s mouth. Deserts have no corners, and there was no but instead uses a halter with a place in which to back the horse’s quarters, but I did what I could. I fine chain passing round the found nothing abnormal and said so, but this did not lead to any nose. With this he controls his follow-up questions. The horsemen seemed satisfied and, to my mare easily and effectively.” surprise, I was presented with a beautifully hand-crafted halter (Figs. 1-4). Nearly 20 Figure 3: “Y” shaped “plumb In January 2013, I met Dr. years passed before I fully bob” connecting noseband Fridtjof Hanson, a retired car- appreciated the signifi- and rope rein. -

Learn About the Double Bridle—The Bits, How It Works, How It Fits and How to Hold the Reins

Learn about the double bridle—the bits, how it works, how it fits and how to hold the reins. By Gerhard Politz Illustrations by Sandy Rabinowitz iders working toward Fourth Level and beyond frequently ask the question, "When is my horse ready for the double bridle?" The answer depends on how your horse accepts the criteria of the Pyramid of Training. In particular, you must evaluate his development of impul- sion and connection. Your horse must work onto a steady contact to the bit. He must flex and bend willingly and fairly evenly in both directions. Ideally, you should be able to feel your horse's hind legs engaging with energy through his back and onto your hands. He must also be able to work with some degree of collection. A question seldom asked by riders is: "When am I ready to use the double bridle?" The answer is: When you can keep your hands still and have learned how to ride half halts. That's the simplified version, but it involves a bit more than that. You must be able to ride your horse resolutely forward, create impulsion as needed and establish an elastic connection. That's already a tall order. You must also carry your hands correctly, holding your fists upright, thumbs on top and pinkies underneath—no "cocktail shaking." Don't hold your hands apart like you are riding August 2008 Dressage Today 47 • Use of THE DOUBLE BRIDLE ANATOMY OF THE SKULL Fitting the Double Bridle To understand the function of the double bridle, and the curb bit in par- ticular, we need to examine the points of contact made in the horse's mouth and on certain areas of the head. -

Standard of Excellence Purebred Arabian Horse

Arabian Horse Society of Australia – Purebred Standard of Excellence The STANDARD OF EXCELLENCE for the PUREBRED ARABIAN HORSE Mare and foal THIS DESCRIPTION APPLIES TO MATURE HORSES compiled by THE ARABIAN HORSE SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED Illustrations by kind permission of PETER UPTON (from his "The Classic Arabian Horse") and SHEILA STUMP (Gallop, Colours and Markings) A six month old filly Page 1 of 21 Arabian Horse Society of Australia – Purebred Standard of Excellence INTRODUCTION The Arabian with a known history going back about five thousand years, is the oldest breed of horse in existence. The earliest records depict his ancestors as war horses in the green crescent of Mesopotamia - swift spirited steeds hitched to chariots or bestrode by marauding warriors. Along with the conquering armies, his forebears and his fame spread throughout the known world. As the prized possession of the great kings and rulers, the Arabian horse became a symbol of power and wealth and he was universally acclaimed as the saddle horse "par excellence." He was the original source of quality and speed, and he remains pre-eminent in the sphere of soundness and endurance. Either directly or ind irectly, the Arabian contributed to the formation of virtually all the modern breeds of light horse. GENERAL APPEARANCE AND IMPRESSION A unique combination of beauty and utility, the typical Arabian is a symmetrical saddle horse combining strength and elegance - with a bright, alert outlook and great pride of bearing. The sharply defined facial features, the thin skin with its silken, iridescent coat, the fine hair of the mane and tail and the hard clean legs with their exceptionally clean cut tendons and joints, are characteristic Arabian features associated with a quality of the highest degree. -

Fitting the Western Or English Saddle to the Horse

August 2008 AG/Equine/2008-05pr Fitting the Western or English Saddle to the Horse Dr. Patricia A. Evans, Extension Equine Specialist, Utah State University Dr. Kerry A. Rood, Extension Veterinarian, Utah State University Introduction horse will find it difficult to work comfortably. A Many times when looking to buy a saddle, comfort horse level through the back will be easier to fit of the rider is the foremost thought. (See “Inspecting and Buying a New or Used Saddle (Figure 1b). A horse low in the withers (mutton (AG/Equine/2008-04pr) and “Selecting a Saddle to withered) (Figure 3) will have excessive pressure Fit the Rider,” AG/Equine/2008-06pr.) Important as at the wither region as the saddle tends to slide rider comfort is, comfort for the horse is as critical, forward. yet often overlooked. There are many aspects that Pressure points from saddle should be considered when fitting a saddle to the Figure 1a. Sway back. horse. The type, size and build of saddle, along with the conformation of the horse, all play a part in a proper fit. If purchasing a saddle, be sure to know what type of riding it will be used for so the appropriate saddle type can be obtained. Saddles for barrel racing are different from cutting or roping saddles; and saddles for dressage are different from cutback saddle seat or hunter type saddles. If you don’t know enough about saddles to identify which type would be most Figure 1b. Level appropriate, visiting with a saddle maker or back. professional horseperson may be helpful. -

How to Identify Balance Saddles

HOW TO IDENTIFY BALANCE SADDLES CURRENT MODELS –Zenith, Felix, Matrix, Nexus, Xtreme, Equinox, Horizon and in the Junior range - Robin, Wren and Bug. The Model will be stamped into the leather of the flap on each side of the saddle, just below the stirrup leather loop. The Style Dressage/GPD/GPJ/Jump) will be stamped in gold or silver foil on the buckle guards of the saddle if made by Frank Baines Saddlery… OR… Stamped into the leather on the back edge of the nearside sweat flap, along with the serial number, seat size and width if made by WRM or The Saddle Company. The seat size and width (in most cases – please see below) will be stamped into the leather on the back edge of the nearside sweat flap, along with the serial number. Here’s a guide to the width stamps: • Zenith (all styles): 6X (narrowest), 7X, 8X and 9X (widest) • Felix (all styles): 6X (narrowest), 7X, 8X and 9X (widest) • (NB: Although the tree widths are the same on both the Zenith and Felix, the flocked panels of the Zenith are bulkier than the foam panels of the Felix saddles, so they do not sit in the same way on the horse) • Matrix (all styles): Regular (narrowest) - in which case there may be NO WIDTH STAMP on the sweat flap X – meaning Xtra and XX - meaning Xtra Xtra (widest) • Nexus Dressage: Regular (narrowest) – in which case there will be NO WIDTH STAMP on the sweat flap, X- meaning Xtra and XX – meaning Xtra Xtra (widest) • Nexus GPD, GPJ and Jump: J1 (narrowest), J2, J3 and J4 (widest) • Horizon (both styles): Apex and Arc (these are similar in width, but shaped differently to accommodate different back shapes, the Apex works better for horses with a more defined wither.