Wednesday, November 20 at 3:00 Pm Or Thursday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan Unexpectedly chosen to be a family manservant, an 11-year-old Barbados sugar plantation slave is initiated into a world of technology and dignity before a devastating betrayal propels him throughout the world in search of his true self. Why you'll like it: Historical fiction. Authentic. Lyrical. Richly detailed. About the Author: Esi Edugyan is author of the novels The Second Life of Samuel Tyne and Half-Blood Blues, which won the Scotiabank Giller Prize and was a finalist for the Man Booker Prize, the Governor General's Literary Award, the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize and the Orange Prize. She lives in Victoria, British Columbia. Questions for Discussion 1. Big Kit tells Washington that “if you dead, you wake up again in your homeland. You wake up free.” How does this line resonate at the end of the book, in the final moments as Wash asks about Dahmoey and looks out into the horizon? 2. Why do you think Big Kit didn’t tell Wash that she was his mother? Do you think he would have responded to Titch’s offer differently had he known? How might his life have been different? 3. Another secret kept in the novel is when Philip delays giving Titch the news of his father’s death – which turns out not to be true. How does this lie compare to Big Kit’s? How is Titch’s response different from Wash’s? 4. Wash describes his scar from the explosion with the Cloud Cutter as “the utter destruction [that] his act had now wrought upon my life.” Discuss the kinds of scar the characters sustain in the novel, both visible and invisible? 5. -

AAM. Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature, Ddavies

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Davies, D. ORCID: 0000-0002-3584-5789 (2021). Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature: Reading Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black. The Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry, 8(1), pp. 1-23. doi: 10.1017/pli.2020.23 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/26525/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/pli.2020.23 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Terrestrial Humanism and the Weight of World Literature: Reading Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black Abstract (151 words) Through an extended reading of Canadian author Esi Edugyan’s novel, Washington Black (2018), this article aims to revise and reinsert both the practice of close reading and a radically revised humanism back into recent World(-)Literature debates. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Margaret Atwood, Esi Edugyan and More Talk About What They Loved Reading When They Were Young, and the Contemporary Books They Recommend for Kids

Canadian authors tell us the books that shaped them (and the ones kids should read today) Margaret Atwood, Esi Edugyan and more talk about what they loved reading when they were young, and the contemporary books they recommend for kids SARAH LAING SPECIAL TO THE GLOBE AND MAIL INCLUDES CORRECTION PUBLISHED APRIL 29, 2021 UPDATED 3 DAYS AGO FOR SUBSCRIBERS 17 COMMENTS SHARE TEXT SIZE BOOKMARK PHOTO ILLUSTRATION THE GLOBE AND MAIL. SOURCE PHOTOS: CHAD HIPOLITO/THE CANADIAN PRESS, JACKIE DIVES/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, HANDOUT, CHRIS YOUNG/THE CANADIAN PRESS, PATRICK DOYLE/THE CANADIAN PRESS, GRAHAM HUGHES/THE CANADIAN PRESS “To learn to read is to light a fire,” wrote Victor Hugo in the 19th century. “Every syllable that is spelled out is a spark.” Nowhere is that aphorism proved truer than in the books that catch the imaginations of children that grow up to be writers themselves – and shape the words that they will one day pen. From the curriculum set piece that overwhelmed a future poet to the Canadian classic that felt like a kindred spirit to a one-day children’s author, these are the pieces of literature that captivated an assemblage of Canadian writers (and one politician). Plus! Some of the contemporary books they’re recommending to the kids in their lives now. READ MORE IN THIS SERIES From graphic novels to audiobooks, tips to get kids reading more Spring 2021 books preview: 45 new titles for you and the young readers in your life Esi Edugyan Two-time Giller Prize-winning author of Washington Black and other novels The book that shaped me as a child … Matilda by Roald Dahl. -

Esi Edugyan's

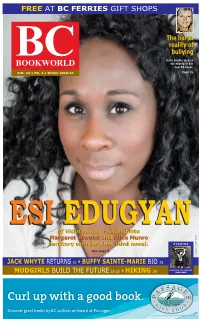

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS TheThe harshharsh realityreality ofof BC bullying bullying Holly Dobbie tackles BOOKWORLD the misery in her new YA novel. VOL. 32 • NO. 4 • Winter 2018-19 PAGE 35 ESIESI EDUGYANEDUGYAN ofof VictoriaVictoria hashas rocketedrocketed intointo MargaretMargaret AtwoodAtwood andand AliceAlice MunroMunro PHOTO territoryterritory withwith justjust herher thirdthird novel.novel. STAMINA POPPITT See page 9 TAMARA JACK WHYTE RETURNS 10 • BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE BIO 25 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT BUILD THE FUTURE 22-23 • 26 MUDGIRLS HIKING #40010086 Curl up with a good book. Discover great books by BC authors on board at Passages. Orca Book Publishers strives to produce books that illuminate the experiences of all people. Our goal is to provide reading material that represents the diversity of human experience to readers of all ages. We aim to help young readers see themselves refl ected in the books they read. We are mindful of this in our selection of books and the authors that we work with. Providing young people with exposure to diversity through reading creates a more compassionate world. The World Around Us series 9781459820913 • $19.95 HC 9781459816176 • $19.95 HC 9781459820944 • $19.95 HC 9781459817845 • $19.95 HC “ambitious and heartfelt.” —kirkus reviews The World Around Us Series.com The World Around Us 2 BC BOOKWORLD WINTER 2018-2019 AROUNDBC TOPSELLERS* BCHelen Wilkes The Aging of Aquarius: Igniting Passion and Purpose as an Elder (New Society $17.99) Christine Stewart Treaty 6 Deixis (Talonbooks $18.95) Joshua -

FICTION by People of Colour (Adult & Teen/YA)

FICTION by People of Colour (adult & teen/YA) These titles are suggested by the Mississippi Mills Public Library staff to support #BlackLivesMatter. These items represent a selection from the Mississippi Mills Public Library collection. Away Running, by David Wright (YA) Love is the Drug, by Alaya Dawn Johns (YA) This Way Home, by Wes Moore (YA) Bay 21, by Matthew Quick (YA) X: A Novel, by Ilyasah Shabazz (YA) Dread nation, by Justina Ireland (YA) If I grow up, by Todd Strasser (YA) Fate of flames, by Sarah Raughley (YA) Paragon Hotel, by Lyndsay Faye Theory, by Dionne Brand I know why the caged bird sings, by Maya Angelou The Hungry Ghosts, by Shyam Selvadurai Everybody's son: a novel, by Thrity N. Umrigar Brother, by David Chariandy Half-blood Blues and Washington Black, both by Esi Edugyan My sister, the serial killer, by O. Braithwaite Dr. Edith Vane and the hares of Crawley Hall, by Suzette Mayr A brief history of seven killings, by Marlon James Mãn: a novel, Vi: a novel, Ru, all by Kim Thúy Colorblind: a story of racism, by Johnathan Harris The Sun is also a Star; Everything, Everything; and Frankly in Love, all by Nicola Yoon (YA) The Hate You Give and On the Come Up, both by Angie Thomas (YA) The Illegal, Some Great Thing, The Book of Negroes, and Any Known Blood, all by Lawrence Hill God Help the Child, A Mercy, Beloved, Song of Solomon, The Bluest Eye, all by Toni Morrison Days by moonlight, Fifteen Dogs, and The Hidden Keys, all by André Alexis They Never Told Me: and other stories and The Polished Hoe, both by Austin Clarke Chronique de la dérive douce: roman and Pays sans chapeau, both by Dany Laferrière Color Purple and Now is the Time to Open Your Heart, both by Alice Walker The Underground Railroad and The Nickel Boys, both by Colson Whitehead The Water Dancer, by Ta Nehisi Coates . -

“How a Girl from Canada Break the Bigtime” Esi Edugyan and the Next Generation of Literary Celebrity in Canada

Lorraine York “How a Girl from Canada Break the Bigtime” Esi Edugyan and the Next Generation of Literary Celebrity in Canada The field of literary celebrity studies has experienced something of a boom in recent years, with exciting studies of British and American modernist writers by the American scholars Jonathan Goldman and Aaron Jaffe and, closer to home, Gillian Roberts’ Prizing Literature: The Celebration and Circulation of National Culture (211), a study of the way in which prize culture marks the Canadian nation state as welcoming or inhospitable to immigrant writers in particular. Such critical activity has taken place within a broader context of renewed attention to literary production conceived as operating within and not necessarily against celebrity culture. These recent studies of literary celebrity are revealing a new modernism: not the elite recoil from tawdry popular culture that many of us were trained to expect from the likes of Eliot, Pound, and Woolf, but a modernism that is fully implicated in celebrity culture. As Goldman observes in his perceptive book, Modernism Is the Literature of Celebrity (211), “literary high modernism and early twentieth-century celebrity . these two supposedly separate aspects of culture are, in truth, mutually constitutive, two sides of the same cultural coin . modernism and celebrity perform similar cultural work on the notion of the exceptional individual” (2). Both modernism and celebrity, that is, work to contemplate and affirm the central role of the individual within mass culture. Along with dearticulating the old narrative of modernism’s antagonistic relationship with popular culture, recent studies of celebrity writers feature an appreciation of the transnational reach of national culture, as well as a renewed awareness that the material aspects of literary culture matter. -

The Great Canadian Reading List: 150 Books to Read for Canada 150

The great Canadian reading list: 150 books to read for Canada 150 1. Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese 32. Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood 2. A Great Reckoning by Louise Penny 33. Saints & Misfits by S.K. Ali 3. Firewater by Harold R. Johnson 34. A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry 4. Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien 35. 419 by Will Ferguson 5. My Best Stories by Alice Munro 36. Celia's Song by Lee Maracle 6. Susceptible by Geneviève Castrée 37. One Hour in Paris by Karyn Freedman 7. The Game by Ken Dryden 38. In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts by Gabor Maté 8. Who Has Seen the by Wind by W.O. Mitchell 39. Birdie by Tracey Lindberg 9. Whylah Falls by George Elliott Clarke 40. Ru by Kim Thúy, translated by Sheila Fischman 10. Obasan by Joy Kogawa 41. Roughing it in the Bush by Susanna Moodie 11. Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel 42. Never Cry Wolf by Farley Mowat 12. The Inconvenient Indian by Thomas King 43. In the Skin of a Lion by Michael Ondaatje 13. Mabel Murple by Sheree Fitch 44. Bloodletting and Miraculous Cures by Vincent Lam 14. The Disappeared by Kim Echlin 45. Half-Breed by Maria Campbell 15. River Thieves by Michael Crummey 46. Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery 16. The Right to Be Cold by Sheila Watt-Cloutier 47. Company Town by Madeline Ashby 17. Montreal's Irish Mafia by D'Arcy O'Connor 48. New Tab by Guillaume Morissette 18. -

Download the Washington Black Tool Kit for Discussion Groups And

Washington Black Tool Kit for Discussion Groups Author Biography: Esi Edugyan Esi Edugyan was born to Ghanaian parents in Alberta, Canada, and raised in Canada. Her work first appeared in anthologies and she is the author of two novels. Her first novel, The Second Life of Samuel Tyne (2005), tells the story of a man who inherits a mansion in a small town in Canada and moves his family there, believing that this is his second chance at life. It was shortlisted for the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. Her second novel, Half- Blood Blues (2011), is about a mixed-race jazz band in World War II Paris and Berlin and what happens after their star trumpeter, Hieronymus Falk, disappears in 1940. In 2011, Half-Blood Blues won the Scotiabank Giller Prize (Canada) and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction, the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize (Canada) and the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction (Canada). Edugyan has also written a work on non-fiction Dreaming of Elsewhere: Observations on Home, published in 2014. Esi Edugyan has taught creative writing at John Hopkins University and the University of Victoria and lives in Victoria, British Columbia. Adapted from https://literature.britishcouncil.org/writer/esi-edugyan Discussion Questions (provided by the publisher) 1. Big Kit tells Washington that “If you dead, you wake up again in your homeland. You wake up free.” How does this line resonate at the end of the book, in the final moments as Wash asks about Dahomey and looks out into the horizon? 2. -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2011/November

AL Direct, November 2, 2011 Contents American Libraries Online ALA News Booklist Online Dallas Update Division News Awards & Grants Seen Online Tech Talk E-Content The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | November 2, 2011 Books & Reading Actions & Answers New This Week Calendar American Libraries Online Libraries tap into crowd power It seemed only natural when one of the most- consulted websites in the world recently posted a ubiquitous banner stating WIKIPEDIA LOVES LIBRARIES. What has resulted is a nationwide “editathon”—editing marathons organized by active Wikipedia users to expand and add depth to the website’s content on a wide range of cultural and historical topics. Dozens of them are taking place in cities across the country, including Atlanta, Boulder, Seattle, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C.... American Libraries news, Nov. 1 School filters reach into students’ homes Pop star Lisa Loeb will Gordon Flagg writes: “The installation of filtering software on bring her wit, wacky computers continues to create problems for students doing humor, and sparkling assignments using computers on their school campuses—and even creativity to the Wrap Up beyond. A survey conducted by the Dartmouth (Mass.) High School’s Rev Up Celebration during student newspaper, The Spectrum, has found that, since the school the Midwinter Exhibits district installed Fortiguard Web Filtering in January, 89% of students Closing on January 23. have had difficulty researching school-related topics on campus. It also reported that students and teachers have been banned from all streaming media.”... AL: Censorship Watch, Nov. 2 Next Steps: Building a competitive advantage Brian Mathews writes: “When Susan Nutter (right) took over the leadership role at North Carolina State University Libraries in Raleigh, it wasn’t a very inspiring organization. -

Book Club Sets

Book Club Sets Fiction Audio Large TitleHeading Author Book Print 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl Mona Awad The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared Jonas Jonasson Accusation Catherine Bush The Alchemist Paulo Coelho NEW! The Alice Network Kate Quinn Alice & Oliver Charles Bock All My Puny Sorrows Miriam Toews All Our Names Dinaw Mengestu All the Light We Cannot See Anthony Doerr American Dervish Ayad Akhtar Art of Racing in the Rain Garth Stein Atonement Ian McEwan Julia Claiborne Be Frank With Me Johnson The Beauty of Humanity Movement Camilla Gibb Before the Fall Noah Hawley Beloved Toni Morrison The Best Kind of People Zoe Whittall The Best Laid Plans Terry Fallis The Betrayers David Bezmozgis Big Little Lies Liane Moriarty Birdie Tracey Lindberg The Bishop's Man Linden MacIntyre The Book of Negroes Lawrence Hill The Bookshop on the Corner Jenny Colgan Calling Me Home Julie Kibler The Casual Vacancy J. K. Rowling The Cat's Table Michael Ondaatje China Dolls Lisa See City of Thieves David Benioff Close to Hugh Marina Endicott Cockroach Rawi Hage A Complicated Kindness Miriam Toews Coventry Helen Humphreys NEW! Crazy Rich Asians Kevin Kwan The Creator's Map Emilio Calderón The Curious Incident of the Dog in Mark Haddon the Night-Time Last Update: Nov 2019 Book Club Sets @ Kitchener Public Library Book Club Sets @ Kitchener Public Library Audio Large Title Author Book Print Dark Matter Blake Crouch De Niro's Game Rawi Hage Delicious! Ruth Reichl Did You Ever Have a Family Bill Clegg Dietland Sarai Walker Digging to America Anne Tyler NEW! The drop Dennis Lhane Educated Tara Westover Elizabeth Costello J.M. -

Book Club Sets Fiction Heading

Book Club Sets Fiction Heading Title Author 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl Mona Awad Accusation Catherine Bush The Alchemist Paulo Coelho Alice & Oliver Charles Bock All Our Names Dinaw Mengestu All the Light We Cannot See Anthony Doerr American Dervish Ayad Akhtar An American Marriage Tayari Jones Anxious People Fredrik Backman The Art of Racing in the Rain Garth Stein Ask Again, Yes Mary Beth Keane Atonement Ian McEwan Be Frank With Me Julia Claiborne Johnson The Beauty of Humanity Movement Camilla Gibb Before the Fall Noah Hawley Beloved Toni Morrison The Best Kind of People Zoe Whittall The Betrayers David Bezmozgis Big Little Lies Liane Moriarty The Book of Longings Sue Monk Kidd The Book of Negroes Lawrence Hill The Bookshop on the Corner Jenny Colgan Calling Me Home Julie Kibler The Cat's Table Michael Ondaatje China Dolls Lisa See City of Thieves David Benioff Close to Hugh Marina Endicott Cockroach Rawi Hage A Complicated Kindness Miriam Toews Crazy Rich Asians Kevin Kwan The Creator's Map Emilio Calderón The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time Mark Haddon Last Update: Aug 2021 Book Club Sets @ Kitchener Public Library Book Club Sets @ Kitchener Public Library Title Author De Niro’s Game Rawi Hage Did You Ever Have a Family Bill Clegg Dietland Sarai Walker Digging to America Anne Tyler The Drop Dennis Lhane Emancipation Day Wayne Grady Everything I Never Told You Celeste Ng Exit West Mohsin Hamid Fifteen Dogs André Alexis The Fire by Night Teresa Messineo Five Days Left Julie Lawson Timmer Fleishman is in Trouble Taffy Brodesser-Akner Fugitive Pieces Anne Michaels The Gap of Time Jeanette Winterson Girl Runner Carrie Snyder The Girl Who Wrote in Silk Kelli Estes The Girls Emma Cline The Glass Hotel Emily St.