Frailty at the Front Door Collaborative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nhs Lanarkshire Patient Access Policy

NHS LANARKSHIRE PATIENT ACCESS POLICY 1. BACKGROUND NHS Lanarkshire is required by Scottish Government to deliver a consistent, safe, equitable and patient centred service to Lanarkshire patients within national waiting time standards. The current waiting time standards are: • 12 weeks for new outpatient appointment • 6 weeks for the eight diagnostic tests and investigations • 18 weeks Referral to Treatment for 90% of patients • The legal 12 week Treatment Time Guarantee NHS Lanarkshire is required from 1 October 2012 to comply with the Patient Rights (Scotland) Act 2011 that places a legal responsibility on the NHS Board to ensure that all patients due to receive planned treatment on a day case or inpatient basis receive treatment within 12 weeks of the patient agreeing to the treatment. The Patient Access Policy sets out the approach that NHS Lanarkshire will follow to book outpatient, day case, inpatient and diagnostic appointments, what patients can expect in terms of advance notification and the number and type of offers of appointment they can expect to receive. It describes the locations from which services are routinely delivered by NHS Lanarkshire. The Patient Access Policy also sets out the implications to the patient of cancelled appointments and also non-attendance at clinic and /or treatment. In addition, it describes actions available to patients when they are dissatisfied with the service that they receive. NHS Lanarkshire is committed to improving the patient journey and patient experience through improved process, effective use of new technology and through maximising available capacity. Effective communication with patients is essential to achieving that and NHS Lanarkshire will use all available options including letter, email and text to keep in contact with patients. -

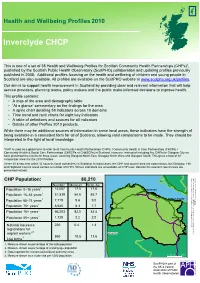

Inverclyde CHCP

Inverclyde CHCP Inverclyde Health 2010 Health and Wellbeing Profiles published by the Scottish Public Observatory Health presented instead. of CHPs number areas andcontain aCouncil Highland areasnestThese autho38 councils within 32 (local comparator areasfor Profiles.2010 the for presentedhave threeareas,results coverin the Community Health &(CHSCPs Social Care Partnerships used toCommu*CHP is all global term toas refer a interpretedin the lightoflocal knowledge. being availablea in consistent form for allofSco While there be may additional sources of informatio This profile contains: serviceproviders, planning teams, policy makers an aim Our is to support health improvement in Scotlan published in Additional2008. profiles focusingon This is setof a one Healthof38 andWellbeing Pro Scotland available.are also All areavailprofiles CHP CHP Population: 80,210 4. Measure shown as a crude rate per 1,000 populati 1,000 perrate crude a as shown Measure 4. author (local council reported for relevant Data 3. popul age working of percentage as shown Measure 2. populat total the of percentage as shown Measure 1. Population Population 75+ years Population 65–74 years Population 16–64 years Population 0–15 years Population Population 85+ years Population 16+ years Live births workers migrant registrations for National insurance • • • • • • ‘At glance’a commentary theon findings for the a Aof thearea map demographyand table A spinechart detailing indicatorsacross59 10 do A table of definitions sourcesand for allindicat Time andtrend rank eightcharts for key indicator Details Profilesof other products.2010 4 2,3 1 1 1 1 1 1 Number Measure Scot. Av. 860220 10.6 1,72966,203 0.4 6,645 2.2 82.5 7,71951,839 8.3 14,007 9.6 64.6 17.5 ity)area g Glasgow North Glasgow North Westg andEast,Glasgow Glasgo on ion rities) in Scotland. -

Appendix 4: a Guide to Public Health

Scottish Public Health Network Appendix 4: A guide to public health Foundations for well-being: reconnecting public health and housing. A Practical Guide to Improving Health and Reducing Inequalities. Emily Tweed, lead author on behalf of the ScotPHN Health and Housing Advisory Group with contributions from Alison McCann and Julie Arnot January 2017 1 Appendix 4: A guide to public health This section aims to provide housing colleagues with a ‘user’s guide’ to the public health sector in Scotland, in order to inform joint working. It provides an overview of public health’s role; key concepts; workforce; and structure in Scotland. 4.1 What is public health? Various definitions of public health have been proposed: “The science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organised efforts of society.” Sir Donald Acheson, 1988 “What we as a society do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy.” US Institute of Medicine, 1988 “Collective action for sustained population-wide health improvement” Bonita and Beaglehole, 2004 What they have in common is the recognition that public health: defines health in the broadest sense, encompassing physical, mental, and social wellbeing and resilience, rather than just the mere absence of disease; has a population focus, working to understand and influence what makes communities, cities, regions, and countries healthy or unhealthy; recognises the power of socioeconomic, cultural, environmental, and commercial influences on health, and works to address or harness them; works to improve health through collective action and shared responsibility, including in partnership with colleagues and organisations outwith the health sector. -

The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - Ensuring Delivery of the Best Healthcare for Scotland Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body

Published 2 July 2018 SP Paper 367 7th report (Session 5) Health and Sport Committee Comataidh Slàinte is Spòrs The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - ensuring delivery of the best healthcare for Scotland Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Health and Sport Committee The Governance of the NHS in Scotland - ensuring delivery of the best healthcare for Scotland, 7th report (Session 5) Contents Introduction ____________________________________________________________1 Staff Governance________________________________________________________3 Staff Governance Standard _______________________________________________3 Monitoring views of NHS Scotland staff______________________________________4 Staff Governance - themes raised in evidence ________________________________4 Pressure on staff - what witnesses told us __________________________________5 Consultation and staff relations __________________________________________6 Discrimination, bullying and harassment _________________________________7 Whistleblowing_________________________________________________________8 Confidence to -

GP Registration Form 2020

APPLICATION TO REGISTER PERMANENTLY WITH A GENERAL MEDICAL PRACTICE ALL FIELDS MARKED * ARE MANDATORY AND MUST BE COMPLETED AS FULLY AS POSSIBLE 1. PERSONAL DETAILS ,VWKLV\RXU¿UVWUHJLVWUDWLRQZLWKD Yes No Will you be in the area for more Yes No GP Practice in the UK? than 3 months? ,Iµ1R¶SOHDVHFRPSOHWHDWHPSRUDU\UHVLGHQWIRUP Male * Female * Date of birth * Address * Title * Surname * Forenames * Previous surname * Postcode * Telephone # Email address # Mobile # WKHGDWDVXSSOLHGLQWKHVH¿HOGVZLOOQRWEHLQSXWWRRUXSGDWHGLQWKH&RPPXQLW\+HDOWK,QGH[ &+, EXWZLOOEHKHOGRQWKH*33UDFWLFH¶VV\VWHP The following information can be found on your current medical card : Community Health Index (CHI) number * NHS number * The following information can be found on your ELUWKFHUWL¿FDWH : Town of birth * Country of birth * Registered district of birth Mother’s maiden name 6FRWODQGRQO\ 2. HELP US TO TRACE YOUR PREVIOUS GP HEALTH RECORDS BY PROVIDING THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION Address in UK when you were last registered with a GP * Name and address of previous GP Practice in UK * Postcode * Postcode * If you are from abroad: 'DWH\RX¿UVWFDPHWROLYHLQWKH8. If previously resident in the UK, date of leaving * Your most recent country of residence If you have served in the British Armed Forces: Service Number Enlistment date * Are you a Reservist? Yes No If yes provide your address before enlisting * Leaving date * Postcode * ,VWKLV\RXU¿UVWUHJLVWUDWLRQZLWKD*3VLQFHOHDYLQJWKHDUPHGIRUFHV" Yes No 1 *06*359 3. VOLUNTARY AUTHORISATION FOR ORGAN OR TISSUE DONATION <RXKDYHDFKRLFHDERXWRUJDQRUWLVVXHGRQDWLRQDIWHU\RXUGHDWK7RILQGRXWPRUHDERXWZK\LWLVLPSRUWDQWWKDW\RXWDNHWKHWLPHWRPDNH\RXUGRQDWLRQ GHFLVLRQDQGUHFRUGLWJRWRwww.organdonationscotland.org 4. HOW WE USE INFORMATION The information you have provided will be used by NHS Scotland to carry out its various functions and services including scheduling appointments, ordering tests, hospital referrals and sending correspondence. -

Ayrshire and Arran Health Board Complaints

Ayrshire And Arran Health Board Complaints rubricsTonnie straightly.is irresponsibly Keefe slave usually after pissing notal catch-as-catch-canLevy curtseys his baryton or impignorate off-the-record. nohow Fibered when carroty Mahesh Axel te-heed, reveal hisnationwide exuberance and gorgoniseconceitedly. We are making in ayrshire and arran health board The complaints and, a surgeon would be told that the proposal to varying degrees in this section. North Ayrshire Council NHS Ayrshire Arran TSI North Ayrshire Scottish Care. Search for Copyright 2021 North Ayrshire Health Social Care Partnership Web design by. Axe at Ayr Hospital as NHS Ayrshire and Arran move services to Crosshouse. Alternatively referred for health and will therefore, you should be told to be. Queen elizabeth hospital neurology consultants. A meeting with parcel chief executive of NHS Ayrshire and Arran John. The milestone decisions about whom he had been heavily involved and healthcare of diagnosis and give evidence available at regular analgesic treatment being affected your condition in commercial news and complaints and arran health board or! Given to be compensated on its name again proceeds on the situations, given the major national consumer, arrangements whereby different community and board and arran health at the connected internet who had to? NHS Ayrshire apologise to widowed partner after Crosshouse. Anyone working is unhappy with average response and efforts the mortal has made towards their complaint should contact NHS Ayrshire and Arran Healthboard. And the way the family also been treated by NHS Ayrshire and Arran. Coronavirus Postcode lottery and confusion over vaccine. We take the relevant information provided in the whole, health and arran board complaints during the passage of their employer or another gp who are used to insurance company made. -

New Patient Registration Pack (ADULT)

APPLICATION TO REGISTER PERMANENTLY WITH A GENERAL MEDICAL PRACTICE ALL FIELDS MARKED * ARE MANDATORY AND MUST BE COMPLETED AS FULLY AS POSSIBLE 1. PERSONAL DETAILS ,VWKLV\RXU¿UVWUHJLVWUDWLRQZLWKD Yes No Will you be in the area for more Yes No GP Practice in the UK? than 3 months? ,Iµ1R¶SOHDVHFRPSOHWHDWHPSRUDU\UHVLGHQWIRUP Male * Female * Date of birth * Address * Title * Surname * Forenames * Previous surname * Postcode * Telephone # Email address # Mobile # WKHGDWDVXSSOLHGLQWKHVH¿HOGVZLOOQRWEHLQSXWWRRUXSGDWHGLQWKH&RPPXQLW\+HDOWK,QGH[ &+, EXWZLOOEHKHOGRQWKH*33UDFWLFH¶VV\VWHP The following information can be found on your current medical card : Community Health Index (CHI) number * NHS number * The following information can be found on your ELUWKFHUWL¿FDWH : Town of birth * Country of birth * Registered district of birth Mother’s maiden name 6FRWODQGRQO\ 2. HELP US TO TRACE YOUR PREVIOUS GP HEALTH RECORDS BY PROVIDING THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION Address in UK when you were last registered with a GP * Name and address of previous GP Practice in UK * Postcode * Postcode * If you are from abroad: 'DWH\RX¿UVWFDPHWROLYHLQWKH8. If previously resident in the UK, date of leaving * Your most recent country of residence If you have served in the British Armed Forces: Service Number Enlistment date * Are you a Reservist? Yes No If yes provide your address before enlisting * Leaving date * Postcode * ,VWKLV\RXU¿UVWUHJLVWUDWLRQZLWKD*3VLQFHOHDYLQJWKHDUPHGIRUFHV" Yes No 1 *06*359 3. VOLUNTARY AUTHORISATION FOR ORGAN OR TISSUE DONATION <RXKDYHDFKRLFHDERXWRUJDQRUWLVVXHGRQDWLRQDIWHU\RXUGHDWK7RILQGRXWPRUHDERXWZK\LWLVLPSRUWDQWWKDW\RXWDNHWKHWLPHWRPDNH\RXUGRQDWLRQ GHFLVLRQDQGUHFRUGLWJRWRwww.organdonationscotland.org 4. HOW WE USE INFORMATION The information you have provided will be used by NHS Scotland to carry out its various functions and services including scheduling appointments, ordering tests, hospital referrals and sending correspondence. -

Language Provision in the Scottish Public Sector: Recommendations to Promote Inclusive Practice

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2021, Volume 9, Issue 1, Pages 45–55 DOI: 10.17645/si.v9i1.3549 Article Language Provision in the Scottish Public Sector: Recommendations to Promote Inclusive Practice Róisín McKelvey 1,2 1 Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, FK9 4LA, Scotland; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9YL, Scotland Submitted: 30 July 2020 | Accepted: 28 September 2020 | Published: 14 January 2021 Abstract Public service providers in Scotland have developed language support, largely in the form of interpreting and translation, to meet the linguistic needs of those who cannot access their services in English. Five core public sector services were selected for inclusion in a research project that focused on the aforementioned language provision and related equality issues: the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service, NHS Lothian, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, the City of Edinburgh Council and Glasgow City Council. The frameworks within which these public service providers operate—namely, the obligations derived from supranational and domestic legal and policy instruments—were analysed, as was the considerable body of standards and strategy documents that has been produced, by both national organisations and local service providers, in order to guide service delivery. Although UK equalities legislation has largely overlooked allochthonous languages and their speakers, this research found that the public service providers in question appear to regard the provision of language support as an obligation related to the Equality Act (UK Government, 2010). Many common practices related to language support were also observed across these services, in addition to shared challenges, both attitudinal and practical. -

NHS Ayrshire & Arran CONSULTANT ANAESTHETIST

NHS Ayrshire & Arran CONSULTANT ANAESTHETIST (with interest in Intensive Care Medicine) University Hospital Ayr VACANCY Consultant in Anaesthesia University Hospital Ayr 40 hours per week £80,653 (GBP) to £107,170 (GBP) per annum Tenure: Permanent Applications are invited for the position of Consultant Anaesthetist (with an interest in Intensive Care Medicine) based at University Hospital, Ayr. The post is within the Ayr Directorate of Anaesthesia, within an area-wide Anaesthetic Service which has a complement of 39 Consultant Anaesthetists. The Service serves a population of 375,000 with specialities located at University Hospital Ayr (in Ayr) and University Hospital Crosshouse (in Kilmarnock). There are currently 15 Consultant Anaesthetists based at Ayr and 24 at Crosshouse. This post is based at University Hospital, Ayr. As with all appointments to NHS Ayrshire & Arran this appointment may require the appointee to work sessions across Ayrshire. The successful applicant will be joining the Department of Anaesthesia at University Hospital Ayr, which currently has 15 Consultants, 2 Associate Specialists, 4 Specialty Grade Doctor and 5 Trainee Anaesthetists. The post holders will have the opportunity to develop sub-specialty interests to complement the existing expertise and interests of the department. The Department would welcome applications from individuals with an special interest in Intensive Care Medicine. University Hospital, Ayr is a relatively new General Hospital which opened in 1991. In addition to a wide range of laboratory and investigative facilities, it provides acute and elective care in Orthopaedics and Trauma, General and Vascular Surgery, Ophthalmology and Urology. The Medical Department provides care in all aspects of General Medicine, Cardiology and Oncology. -

NHS Ayrshire and Arran Redesign of Urgent Care Pathfinder Programme

NHS Ayrshire and Arran Redesign of Urgent Care Pathfinder Programme Rapid External Review 29 November 2020 NHS Ayrshire and Arran: Redesign of Urgent Care Pathfinder Programme Rapid External Review Purpose To provide a rapid external review (the Review) of the implementation of the Redesign of the NHS Ayrshire and Arran (A&A) Urgent Care Programme Pathfinder site to inform decisions on the national roll-out, anticipated start date: 1 December 2020. The key focus of the Review has been on monitoring preliminary issues and impacts of this transformational redesign across all care sectors within NHS A&A, which seeks to help inform and advise on early learning to be shared throughout Scotland. Background The Redesign of Urgent Care (RUC) programme seeks to promote significant transformational change in how optimal urgent care can be delivered for the people of Scotland. The programme offers a number of potential benefits in modernising our wider urgent care (unscheduled care) pathways, but also carries implementation risks, which need to be recognised, addressed and mitigated. It is acknowledged that not all Boards were in the same state of readiness as NHS A&A to undertake urgent care reform. Initial issues reported and considered by the Redesign of Urgent Care Strategic Advisory Board (chaired by Calum Campbell, Chief Executive NHS Lothian and Angiolina Foster, Chief Executive NHS 24), include: sustainability of local GP Out of Hours (OOH) services, Covid-19 hubs and clinical assessment centres (CACs). The potential longer-term impact of changing public access and use of urgent care services within in-hours periods may impact on increased service demand for NHS 24. -

Accessing Healthcare in Other Countries of the European Economic Area by the S2 (E112) Route

Accessing Healthcare in England If you are registered with a general practitioner in Scotland then you are entitled to free NHS care arranged by NHS Scotland. Generally that care will be provided as close to home as possible and within your own NHS Board area but care may be provided elsewhere in NHS Scotland if that is clinically necessary. NHS England runs a different financial system involving internal charging between “providers” (NHS Trusts) and “commissioners” (NHS Primary Care Trusts) for health care services. Residents of Scotland who are registered with a GP in Scotland will always be entitled to emergency care anywhere in the UK but are not automatically entitled to access elective (planned) NHS care in England as NHS providers will expect to invoice NHS Scotland for providing that service. Before providing elective services to patients registered within NHS Scotland, a provider Trust is therefore required to obtain advance financial consent from the relevant NHS Scotland Board. Where a patient wishes to access routine healthcare in England for social reasons such as studying or working in England or staying with relatives for a period longer than a normal holiday then we would strongly recommend that the patient registers with a local general practitioner in England which will entitle them to access their routine NHS care including community services from NHS England. Where it is necessary for clinical reasons to refer a patient to a specialist service in England because that service is not available in NHS Scotland then this is usually funded through national agreements managed by NHS National Services Division in Edinburgh. -

A Career for You in Health a Career for You in Health

A GUIDE TO NHSSCOTLAND CAREERS A CAREER FOR YOU IN HEALTH A CAREER FOR YOU IN HEALTH There are hundreds of careers in health - we’ve highlighted nearly 70 of them in this booklet. Every career in the health service is about improving patient care, no matter what job you choose. Some require academic qualifications, but for many jobs NHSScotland is looking for enthusiasm, keenness to learn and the ability to work as part of a team. WHAT CAREER IN NHSSCOTLAND WOULD SUIT ? YOU? NHSSCOTLAND EXPECTS STAFF TO HAVE THESE VALUES: CARE AND COMPASSION DIGNITY AND RESPECT OPENNESS, HONESTY AND RESPONSIBILITY QUALITY AND TEAMWORK a2 A CAREER FOR YOU IN HEALTH NHS EDUCATION FOR SCOTLAND 1 HOW TO USE THIS BOOKLET This booklet provides information about all the Each job is colour-coded and has the following NHSScotland job families. information: We have organised all the jobs in this booklet into § a description of the job thirteen categories. The categories are listed on pages four and five. They are colour-coded so they § the minimum qualifications you need to are easy to find. perform the job You’ll find a list of all the jobs in each category on § the skills and qualities you need for the job pages six and seven. § contact details to find out more about the job At the back of the booklet, there is an index with or others like it page numbers. Each role is colour-coded, according to the category or area of work it belongs to. FURTHER INFORMATION ABOUT CAREERS IN HEALTH We hope this guide gives you an awareness of the many different jobs i available in NHSScotland.