Protriptyline Hcl Tablets, USP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acute Extrapyramidal Symptoms Following Abrupt Discontinuation of Propranolol

Medical Journal of the Volume 14 Islamic Republic of Iran Number 3 Fall 1379 November 2000 ACUTE EXTRAPYRAMIDAL SYMPTOMS FOLLOWING ABRUPT DISCONTINUATION OF PROPRANOLOL A. ALAVIAN GHAVANINI From the Center Jor Research Consultation, School oj Medicine, Shiraz University ojMedical Sciences, Shiraz, I.R. Iran. ABSTRACT A case of acute extrapyramidal manifestations consisting of dystonia and akathisia following abrupt discontinuation of propranolol is reported. She re sponded well to oral propranolol and intramuscular diazepam. Extrapyramidal symptoms have commonly been associated with acute or chronic administration of neuroleptic drugs. There have been reports of a substantial number of cases with similar clinical characteristics associated with tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Al though it is known that beta-adrenoceptor antagonists are effective in the treat ment of extrapyramidal symptoms, especially akathisia, there has been no previ ous report of such symptoms induced by abrupt withdrawal of these drugs. Al though she had been on low dose amitriptyline and had discontinued this medica tion long before, prolonged use of amitriptyline may have had a predisposing role in the development of these symptoms. MJIRL Vol. 14, No.3, 305-306, 2000. Keywords: Propranolol; Extrapyramidal symptoms; Beta-adrenoceptor antagonists. INTRODUCTION She described a feeling of "being pulled down by gravity." She had never experienced such symptoms before. Thor Extrapyramidal symptoms include acute dystonias, ough physical examination with special focus on the ner akathisia, Parkinson's syndrome, and tardive dyskinesia. vous system was unremarkable except for the involuntary These symptoms are common manifestations of neurolep contraction of jaw muscles and a fine tremor in her ex tic drugs. -

Prevalence of Extrapyramidal Side Effects in Patients on Antipsychotics Drugs at a Tertiary Care Center

f Ps al o ych rn ia u tr o y J Kirgaval et al., J Psychiatry 2017, 20:5 Journal of Psychiatry DOI: 10.4172/2378-5756.1000419 ISSN: 2378-5756 Research Article Open Access Prevalence of Extrapyramidal Side Effects in Patients on Antipsychotics Drugs at a Tertiary Care Center5 Ramprasad Santhanakrishna Kirgaval1*, Srinivas Revanakar2 and Chidanand Srirangapattna2 1Department of Psychiatry, Shimoga Institute of Medical Sciences, Shimoga, Karnataka, India 2Department of Pharmacology, Shimoga Institute of Medical Sciences, Shimoga, Karnataka, India Abstract Background: Antipsychotic drugs are associated with adverse effects that can lead to poor medication adherence, stigma, distress and impaired quality of life. Among the various side effects of anti-psychotics extra pyramidal symptoms constitute one of the important side effects interfering with the compliance of the patients towards medication. Objective: Evaluation of extrapyramidal side effects by AIMS in patients who are on antipsychotics. Results: The extrapyramidal symptoms were more commonly seen in males (62.85%), the age of incidence of maximum in the age group of 34.28, Maximum was seen among the patients on the Risperidone (45.7%), Involvement of the extremities was common (42.85%) and 64.28% of individuals had moderate severity and 54.28% of individuals were aware of the extrapyramidal symptoms which provided mild distress. Conclusion: Extrapyramidal symptoms are one of the commonest side effect of the antipsychotics interfering with compliance of the patients towards adherence to medications, thereby decreasing the efficacy. Keywords: Extrapyramidal symptoms; Compliance; Antipsychotics; positive symptom of the psychosis but have some serious limitations AIMS. such as lack of efficacy against negative symptoms and adverse effects like extrapyramidal symptoms [7]. -

Modern Antipsychotic Drugs: a Critical Overview

Review Synthèse Modern antipsychotic drugs: a critical overview David M. Gardner, Ross J. Baldessarini, Paul Waraich Abstract mine was based primarily on the finding that dopamine ago- nists produced or worsened psychosis and that antagonists CONVENTIONAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUGS, used for a half century to treat were clinically effective against psychotic and manic symp- a range of major psychiatric disorders, are being replaced in clini- 5 toms. Blocking dopamine D2 receptors may be a critical or cal practice by modern “atypical” antipsychotics, including ari- even sufficient neuropharmacologic action of most clinically piprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone and effective antipsychotic drugs, especially against hallucina- ziprasidone among others. As a class, the newer drugs have been promoted as being broadly clinically superior, but the evidence for tions and delusions, but it is not necessarily the only mecha- this is problematic. In this brief critical overview, we consider the nism for antipsychotic activity. Moreover, this activity, and pharmacology, therapeutic effectiveness, tolerability, adverse ef- subsequent pharmacocentric and circular speculations about fects and costs of individual modern agents versus older antipsy- altered dopaminergic function, have not led to a better un- chotic drugs. Because of typically minor differences between derstanding of the pathophysiology or causes of the several agents in clinical effectiveness and tolerability, and because of still idiopathic psychotic disorders, nor have they provided a growing concerns about potential adverse long-term health conse- non-empirical, theoretical basis for the design or discovery quences of some modern agents, it is reasonable to consider both of improved treatments for psychotic disorders. older and newer drugs for clinical use, and it is important to inform The neuropharmacodynamics of specific modern anti- patients of relative benefits, risks and costs of specific choices. -

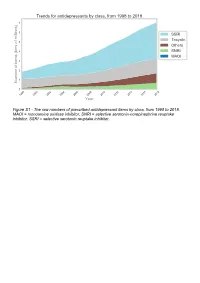

The Raw Numbers of Prescribed Antidepressant Items by Class, from 1998 to 2018

Figure S1 - The raw numbers of prescribed antidepressant items by class, from 1998 to 2018. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor, SNRI = selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Figure S2 - The raw numbers of prescribed antidepressant items for the ten most commonly prescribed antidepressants (in 2018), from 1998 to 2018. Figure S3 - Practice level percentile charts for the proportions of the ten most commonly prescribed antidepressants (in 2018), prescribed between August 2010 and November 2019. Deciles are in blue, with median shown as a heavy blue line, and extreme percentiles are in red. Figure S4 - Practice level percentile charts for the proportions of specific MAOIs prescribed between August 2010 and November 2019. Deciles are in blue, with median shown as a heavy blue line, and extreme percentiles are in red. Figure S5 - CCG level heat map for the percentage proportions of MAOIs prescribed between December 2018 and November 2019. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Figure S6 - CCG level heat maps for the percentage proportions of paroxetine, dosulepin, and trimipramine prescribed between December 2018 and November 2019. Table S1 - Antidepressant drugs, by category. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor, SNRI = selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Class Drug MAOI Isocarboxazid, moclobemide, phenelzine, tranylcypromine SNRI Duloxetine, venlafaxine SSRI Citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, -

1 Abietic Acid R Abrasive Silica for Polishing DR Acenaphthene M (LC

1 abietic acid R abrasive silica for polishing DR acenaphthene M (LC) acenaphthene quinone R acenaphthylene R acetal (see 1,1-diethoxyethane) acetaldehyde M (FC) acetaldehyde-d (CH3CDO) R acetaldehyde dimethyl acetal CH acetaldoxime R acetamide M (LC) acetamidinium chloride R acetamidoacrylic acid 2- NB acetamidobenzaldehyde p- R acetamidobenzenesulfonyl chloride 4- R acetamidodeoxythioglucopyranose triacetate 2- -2- -1- -β-D- 3,4,6- AB acetamidomethylthiazole 2- -4- PB acetanilide M (LC) acetazolamide R acetdimethylamide see dimethylacetamide, N,N- acethydrazide R acetic acid M (solv) acetic anhydride M (FC) acetmethylamide see methylacetamide, N- acetoacetamide R acetoacetanilide R acetoacetic acid, lithium salt R acetobromoglucose -α-D- NB acetohydroxamic acid R acetoin R acetol (hydroxyacetone) R acetonaphthalide (α)R acetone M (solv) acetone ,A.R. M (solv) acetone-d6 RM acetone cyanohydrin R acetonedicarboxylic acid ,dimethyl ester R acetonedicarboxylic acid -1,3- R acetone dimethyl acetal see dimethoxypropane 2,2- acetonitrile M (solv) acetonitrile-d3 RM acetonylacetone see hexanedione 2,5- acetonylbenzylhydroxycoumarin (3-(α- -4- R acetophenone M (LC) acetophenone oxime R acetophenone trimethylsilyl enol ether see phenyltrimethylsilyl... acetoxyacetone (oxopropyl acetate 2-) R acetoxybenzoic acid 4- DS acetoxynaphthoic acid 6- -2- R 2 acetylacetaldehyde dimethylacetal R acetylacetone (pentanedione -2,4-) M (C) acetylbenzonitrile p- R acetylbiphenyl 4- see phenylacetophenone, p- acetyl bromide M (FC) acetylbromothiophene 2- -5- -

Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014

Federal Bureau of Prisons Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014 Table of Contents 1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Natural History ................................................................................................................................. 2 Special Considerations ...................................................................................................................... 2 3. Screening ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Screening Questions .......................................................................................................................... 3 Further Screening Methods................................................................................................................ 4 4. Diagnosis ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Depression: Three Levels of Severity ............................................................................................... 4 Clinical Interview and Documentation of Risk Assessment............................................................... -

In Search of a Generic Chiral Strategy: 101 Separations with One Method

32 September 2009 In Search of a Generic Chiral Strategy: 101 Separations With One Method Jim Thorn and John C. Hudson, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA In any approach to drug discovery, the challenges presented to the analytical chemist are compounded when a product contains one or more chiral centres. Enantiomers are stereoisomers that display chirality, having one or more asymmetric carbon centres, allowing them to exist as non-superimposable mirror images of one another. These isomers are difficult to analyze as they are both physically and chemically identical and differ only in the way they bend plane-polarized light and in their behaviour in a chiral environment. The key to separating enantiomers is to first enantiomeric drug substances. A group of Boniface Hospital, Winnipeg, MB, Canada. create diastereomers from these compounds selected from a set of drugs Solutions of these drug and metabolite enantiomers. Diastereomers may be and metabolites of pharmaceutical and standards were purchased or prepared at a created through chemical derivatization forensic interest was separated using concentration of 1mg/mL and diluted to with a “chiral” reagent, or they may be HSCDs. This was a challenging group 25ppm (25ng/ µL) in water. formed transiently through interactions with because it included many closely related Reference Marker: 1,3,6,8- chiral selectors. The latter, of course, is metabolites of drug substances, in addition Pyrenetetrasulfonate (PTS), 10mM in water: usually the most desirable as it is the easiest to the parent drugs. For simplicity, the 2µL added to each sample. to employ. These chiral selectors have screening strategy was designed to historically been introduced in the form of separate the enantiomers of individual Instrument: P/ACE™ MDQ Capillary chromatographic media using HPLC, SFC or compounds, although we present Electrophoresis System (Beckman Coulter, GC as the separation technique. -

Fatal Toxicity of Antidepressant Drugs in Overdose

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 295 24 OCTOBER 1987 1021 Br Med J (Clin Res Ed): first published as 10.1136/bmj.295.6605.1021 on 24 October 1987. Downloaded from PAPERS AND SHORT REPORTS Fatal toxicity of antidepressant drugs in overdose SIMON CASSIDY, JOHN HENRY Abstract dangerous in overdose, thus meriting investigation of their toxic properties and closer consideration of the circumstances in which A fatal toxicity index (deaths per million National Health Service they are prescribed. Recommendations may thus be made that prescriptions) was calculated for antidepressant drugs on sale might reduce the number offatalities. during the years 1975-84 in England, Wales, and Scotland. The We used national mortality statistics and prescription data tricyclic drugs introduced before 1970 had a higher index than the to compile fatal toxicity indices for the currently available anti- mean for all the drugs studied (p<0-001). In this group the depressant drugs to assess the comparative safety of the different toxicity ofamitriptyline, dibenzepin, desipramine, and dothiepin antidepressant drugs from an epidemiological standpoint. Owing to was significantly higher, while that ofclomipramine, imipramine, the nature of the disease these drugs are particularly likely to be iprindole, protriptyline, and trimipramine was lower. The mono- taken in overdose and often cause death. amine oxidase inhibitors had intermediate toxicity, and the antidepressants introduced since 1973, considered as a group, had significantly lower toxicity than the mean (p<0-001). Ofthese newer drugs, maprotiline had a fatal toxicity index similar to that Sources ofinformation and methods of the older tricyclic antidepressants, while the other newly The statistical sources used list drugs under their generic and proprietary http://www.bmj.com/ introduced drugs had lower toxicity indices, with those for names. -

Data Sheet SURMONTIL Trimipramine (As Maleate) 25 Mg Tablets and 50 Mg Capsules

Data Sheet SURMONTIL trimipramine (as maleate) 25 mg tablets and 50 mg capsules Presentation SURMONTIL tablets are compression coated, white or cream, circular, biconvex, containing the equivalent of 25mg trimipramine (as maleate) with a diameter of about 8.0mm. The face is indented with the name and strength, reverse plain. SURMONTIL capsules are opaque white with opaque green cap, printed SU50, each containing the equivalent of 50mg trimipramine (as maleate). Uses Actions SURMONTIL has a potent anti-depressant action similar to that of other tricyclic anti-depressants. The mechanism of action is not fully understood but it is thought to be via inhibition of neuronal re- uptake of noradrenalin, thereby increasing availability. SURMONTIL also possesses a pronounced sedative action. Pharmacokinetics SURMONTIL is readily absorbed after oral administration, reaching a mean peak plasma level after 3 hours. High first pass hepatic clearance results in a mean bioavailability of about 41% of the oral dose, and trimipramine is extensively protein bound in plasma. Elimination half-life is 24 hours. Metabolism is in the liver to its major metabolite, desmethyltrimipramine, which is excreted mainly in the urine. Indications SURMONTIL is indicated in the treatment of depressive illness, especially where sleep disturbance, anxiety or agitation is a presenting symptom. Sleep disturbance is controlled within 24 hours and true anti-depressant action follows within 7-10 days. Dosage and Administration Adults Mild/Moderate Depression in General Practice: The recommended dosage is 50-75 mg orally given two hours before bedtime, the larger dose (75 mg) being preferable for those patients with more marked sleep disturbance. -

Effects of Sympathetic Inhibition on Receptive, Proceptive, and Rejection Behaviors in the Female Rat

Physiology & Behavior, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 537-542, 1996 Copyright © 1996 Elsevier Science Inc. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0031-9384/96 $15.00 + .00 ELSEVIER 0031-9384(95)02102-2 Effects of Sympathetic Inhibition on Receptive, Proceptive, and Rejection Behaviors in the Female Rat CINDY M. MESTON, 1 INGRID V. MOE AND BORIS B. GORZALKA Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, 2136 West Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1Z4 Received 27 September 1994 MESTON, C. M., I. V. MOE AND B. B. GORZALKA. Effects of sympathetic inhibition on receptive, proceptive, and rejection behaviors in the female rat. PHYSIOL BEHAV 59(3) 537-542, 1996.--The present investigation was designed to examine the effects of sympathetic nervous system (SNS) inhibition on sexual behavior in ovariec- tomized, steroid-treated female rats. Clonidine, an alpha2-adrenergic agonist, guanethidine, a postganglionic noradren- ergic blocker, and naphazoline, an alpha2-adrenoreceptor agonist were used to inhibit SNS activity. Intraperitoneal injections of eit:aer 33/zg/ml or 66/xg/ml clonidine significantly decreased receptive (lordosis) and proceptive (ear wiggles) behaviors and significantly increased rejection behaviors (vocalization, kicking, boxing). Either 25 mg/ml or 50 mg/ml guanethidine significantly decreased receptive and proceptive behavior and had no significant effect on rejection behav!iors. Naphazoline significantly inhibited lordosis behavior at either 5 mg/ml or 10 mg/ml doses, significantly inhibited proceptive behavior at 5 mg/ml, and had no significant effect on rejection behaviors. These findings supporc the hypothesis that SNS inhibition decreases sexual activity in the female rat. Lordosis Proceptive behavior Rejection behavior Clonidine Guanethidine Naphazoline Alpha-adrenergic INTRODUCTION as 2 /xg/animal also inhibits lordosis behavior (1). -

(Mibg) Scintigraphy: Procedure Guidelines for Tumour Imaging

Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging (2010) 37:2436–2446 DOI 10.1007/s00259-010-1545-7 GUIDELINES 131I/123I-Metaiodobenzylguanidine (mIBG) scintigraphy: procedure guidelines for tumour imaging Emilio Bombardieri & Francesco Giammarile & Cumali Aktolun & Richard P. Baum & Angelika Bischof Delaloye & Lorenzo Maffioli & Roy Moncayo & Luc Mortelmans & Giovanna Pepe & Sven N. Reske & Maria R. Castellani & Arturo Chiti Published online: 20 July 2010 # EANM 2010 Abstract The aim of this document is to provide general existing procedures for neuroendocrine tumours. The information about mIBG scintigraphy in cancer patients. guidelines should therefore not be taken as exclusive of The guidelines describe the mIBG scintigraphy protocol other nuclear medicine modalities that can be used to obtain currently used in clinical routine, but do not include all comparable results. It is important to remember that the The European Association has written and approved guidelines to promote the use of nuclear medicine procedures with high quality. These general recommendations cannot be applied to all patients in all practice settings. The guidelines should not be deemed inclusive of all proper procedures and exclusive of other procedures reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The spectrum of patients seen in a specialized practice setting may be different than the spectrum usually seen in a more general setting. The appropriateness of a procedure will depend in part on the prevalence of disease in the patient population. In addition, resources available for patient care may vary greatly from one European country or one medical facility to another. For these reasons, guidelines cannot be rigidly applied. These guidelines summarize the views of the Oncology Committee of the EANM and reflect recommendations for which the EANM cannot be held responsible. -

Association of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors with the Risk for Spontaneous Intracranial Hemorrhage

Supplementary Online Content Renoux C, Vahey S, Dell’Aniello S, Boivin J-F. Association of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the risk for spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage. JAMA Neurol. Published online December 5, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4529 eMethods 1. List of Antidepressants for Cohort Entry eMethods 2. List of Antidepressants According to the Degree of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibition eMethods 3. Potential Confounding Variables Included in Multivariate Models eMethods 4. Sensitivity Analyses eFigure. Flowchart of Incident Antidepressant (AD) Cohort Definition and Case- Control Selection eTable 1. Crude and Adjusted Rate Ratios of Intracerebral Hemorrhage Associated With Current Use of SSRIs Relative to TCAs eTable 2. Crude and Adjusted Rate Ratios of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Associated With Current Use of SSRIs Relative to TCAs eTable 3. Crude and Adjusted Rate Ratios of Intracranial Extracerebral Hemorrhage Associated With Current Use of SSRIs Relative to TCAs. eTable 4. Crude and Adjusted Rate Ratios of Intracerebral Hemorrhage Associated With Current Use of Antidepressants With Strong Degree of Inhibition of Serotonin Reuptake Relative to Weak eTable 5. Crude and Adjusted Rate Ratios of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Associated With Current Use of Antidepressants With Strong Degree of Inhibition of Serotonin Reuptake Relative to Weak eTable 6. Crude and Adjusted Rate Ratios of Intracranial Extracerebral Hemorrhage Associated With Current Use of Antidepressants With Strong Degree of Inhibition of Serotonin Reuptake Relative to Weak This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/02/2021 eMethods 1.