Heritage Statement Former Ashlyn's Farm Site, Chesham Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memories of a Lifetime in Berkhamsted

Your Berkhamsted editorial From the Editor July 2012 The Parish Magazine of Contents St Peter's Great Berkhamsted Leader by Richard Hackworth 3 Welcome to the July issue of Your Around the town 5 Berkhamsted. Read all about us 7 The weather may still not be what we’d like for summer but in true British spirit it Back to the outdoors 9 doesn’t stop us celebrating. The jubilee weekend may have had us all reaching for The Black Ditch, the dungeon the umbrellas but the cloud did break at and the parachute 12 times for the High Street party and it was a beautiful evening for the celebrations later Sport—cricket 14 at Ashlyns School and the many street parties around town. At Ashlyns it was Christians against poverty 15 encouraging to see so many people come together from the community, picnic Hospice News 16 blankets in tow, just relaxing, chatting and enjoying being part of such a lovely town. Parish news 18 On the subject of celebrations, the Berkhamsted Games 2012 take place this Summer garden 20 month on 5th July, not forgetting of course the 2012 Olympics, and our own magazine Memories of a lifetime in is 140 years old! So, more reasons to keep Berkhamsted 23 that union jack bunting flying and carry on regardless of the great British weather. Chilterns Dog Rescue 27 To celebrate our anniversary we have two Recipe 28 articles by Dan Parry: one looking back at Berkhamsted in 1872 and another where The Last Word 31 he chats to a long-term Berkhamsted resident Joan Pheby, born in 1924, about front cover. -

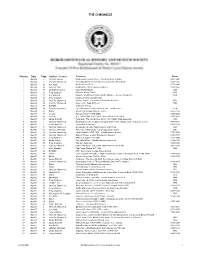

Chronicle Contents

THE CHRONICLE Volume Date Page Author / Source Contents Dates I Mar-04 5 Jennifer Honour Berkhamsted connections - Cicely the Rose of Raby 1415-1495 I Mar-04 6 Jennifer Sherwood Percy Birtchnell (1910-1986), local historian 'Beorcham' 1910-1986 I Mar-04 10 Ann Nath Marlin Chapel Farm 1272-1485 I Mar-04 16 Museum Store Berkhamsted Place (home of Finch) 1588-1967 I Mar-04 18 Michael Browning Figg's The Chemists 1277 I Mar-04 21 Tony Statham Kingshill Water Tower 1935 I Mar-04 23 Eric Holland Britwell, Berkhamsted Hill (Castle Village) / Cooper family tree 1904 I Mar-04 26 Tony Statham Listing of Historical Buildings I Mar-04 29 Jennifer Sherwood Ashlyns School, formerly the Foundling Hospital 1739 I Mar-04 34 Jennifer Sherwood New Lodge, Bank Mill Lane 1788 I Mar-04 37 BLH&MS Collection Policy I Mar-04 38 Jennifer Sherwood The Duncombe Family of Barley End - family letter 1774 I Mar-04 43 Editor A local chronology (1066 to 1939) 1066-1939 I Mar-04 47 Society Barbara Russell (1910-2002) 1910-2002 I Mar-04 47 Society H.E. Pullen 'Jim' (1912-2003), Vera Pullen (1915-2003) 1912-2003 I Mar-04 48 Leslie Mitchell Tailpiece - The corner shop (from 1994 Family Tree Magazine) 1994 II Mar-05 3 Jennifer Sherwood Biographical note on Edward Popple (1879-1960), Headmaster of Victoria School 1879-1960 II Mar-05 7 Leslie Mitchell "It was but yesterday…" 1929-1939 II Mar-05 11 Jennifer Sherwood Gorseside - Ancient Farmhouse to Site Office 1607 II Mar-05 15 Veronica Whinney Memories of Gorseside - my grandparents' home 1901 II Mar-05 18 Jennifer Sherwood -

Berkhamsted Heritage Network and Hub – Main Report Appendices

Berkhamsted Heritage Hub and Network Berkhamsted Heritage Network and Hub – Main Report Appendices 1 Destination Audit 78 2 Heritage Groups 87 3 Collections 91 4 Arts Groups in Berkhamsted 94 5 Museums & Heritage Centres 96 6 History Festivals 99 7 “Berkhamsted - Ten Centuries Through Ten Stories” - Worked Example of Events and Performances Proposal 105 8 Increasing Enjoyment of Heritage by Young People and Working with Schools 113 9 The Historic Environment (M Copeman Report) 10 BLHMS Collections Analysis (E. Toettcher report) 11 HKD Digitisation and Digital / Virtual Interpretation 12 Workshop Notes 13 Socio-Demographic Profile – Berkhamsted 14 Socio-Demographic Profile – 30 Minute Drive Time 77 Berkhamsted Heritage Hub and Network 1 Destination Audit 1.1 Access The A4251 runs through the centre of Berkhamsted. It connects to the A41, which runs adjacent to the town. The A41 connects in the east to the M1 and M25. Figure 48: Distance & Drive Time to large towns & cities Name Distance (mi.) Drive Time (mins) Tring 6.7 13 Hemel Hempstead 7.4 15 Watford 12.6 25 Aylesbury 13.8 22 Leighton Buzzard 14.3 31 High Wycombe 15.2 35 Luton 18.2 32 Source: RAC Route Planner There are currently 1,030 parking places around the town. Most are charged. Almost half are at the station, most of which are likely to be used by commuters on weekdays but available for events at weekends. A new multi-storey will open in 2019 to alleviate parking pressures. This is central to the town, next to Waitrose, easy to find, and so it will a good place to locate heritage information. -

School Allocation Summary Report - Main Allocation Day - 02/03/2020 NOTES

HERTFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL CHILDREN’S SERVICES Secondary / Upper / Yr 10 Transfer School Allocation Summary Report - Main Allocation Day - 02/03/2020 NOTES: 1. To view the allocation summary for a specific school, click on the school name in the Index. 2. To print the allocation summary for a specific school, click File > Print, and then specify the page numbers from the index below. School Town Phase Page Adeyfield Academy (The) Hemel Hempstead Secondary 3 Ashlyns School Berkhamsted Secondary 4 Astley Cooper School (The) Hemel Hempstead Secondary 5 Barclay Academy Stevenage Secondary 6 Barnwell School Stevenage Secondary 7 Beaumont School St Albans Secondary 8 Birchwood High School Bishop's Stortford Secondary 9 Bishop's Hatfield Girls' School Hatfield Secondary 10 Bishop's Stortford High School (The) Bishop's Stortford Secondary 12 Broxbourne School (The) Broxbourne Secondary 13 Bushey Academy (The) Bushey Secondary 14 Bushey Meads School Bushey Secondary 15 Chancellor's School Brookmans Park Secondary 16 Chauncy School Ware Secondary 17 Croxley Danes School Croxley Green Secondary 18 Dame Alice Owen's School Potters Bar Secondary 19 Elstree University Technical College Elstree Year 10 20 Fearnhill School Maths and Computing College Letchworth Secondary 21 Francis Combe Academy Garston Secondary 22 Freman College Buntingford Upper 23 Goffs Academy Cheshunt Secondary 24 Goffs-Churchgate Academy Cheshunt Secondary 25 Haileybury - Turnford School Cheshunt Secondary 26 Hemel Hempstead School (The) Hemel Hempstead Secondary 27 Hertfordshire -

My Life As a Foundling 23 Your Community News for Future Issues

Your Berkhamsted editorial From the Editor May 2011 The Parish Magazine of Contents St Peter's Great Berkhamsted Leader by Fr Michael Bowie 3 Around the town: local news 5 Welcome to the May issue of Your Berkhamsted. Hospice News 9 In this month’s issue we continue our celebrations of the 60th anniversary of Sam Limbert ‘s letter home 11 Ashlyns School with a fascinating first hand account of life as a foundling at the Berkhamsted’s visitors from Ashlyns Foundling Hospital. space 12 Dan Parry tells us how we can get a glimpse of life in space from our own back Little Spirit - Chapter 8 14 gardens while Corinna Shepherd talks about dyslexia in children and her Parish News 16 upcoming appearance at Berkhamsted Waterstone’s. Is your child dyslexic? 20 We bring you the latest news from “Around the town” - please let us know My life as a foundling 23 your community news for future issues. Parish life 27 This month we also have features about the Ashridge Annual Garden Party, the Petertide Promises Auction, and a very Buster the dog 28 clever dog, as well as our regular columnists, and the eighth and penultimate The local beekeeper 29 chapter of our serial Little Spirit. Your Berkhamsted needs you! 31 Ian Skillicorn, Editor We welcome contributions, suggestions for articles and news items, and readers’ letters. For all editorial and advertising contacts, please see page 19. For copy dates for June to August’s issues , please refer to page 30. Front cover: photo courtesy of Cynthia Nolan - www.cheekychopsphotos.co.uk. -

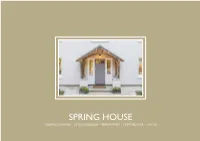

Spring House

SPRING HOUSE HUDNALL COMMON • LITTLE GADDESDEN • BERKHAMSTED • HERTFORDSHIRE • HP4 1QJ SPRING HOUSE Hudnall Common • little Gaddesden BerkHamsted • HertfordsHire • HP4 1QJ A SUBSTANTIAL AND ELEGANT COUNTRY HOME IN A WONDERFUL WOODLAND SETTING LOWER GROUND FLOOR GAMES ROOM, HOME OFFICE, LAUNDRY ROOM, BOILER/PLANT ROOM, SHOWER ROOM, STORE ROOMS GROUND FLOOR ENTRANCE HALL, DRAWING/DINING ROOM, PLAYROOM, KITCHEN/BREAKFAST ROOM, UTILITY ROOM, 3 BEDROOMS (1 WITH EN SUITE), BATHROOM, CLOAKROOM FIRST FLOOR MASTER BEDROOM WITH EN SUITE, 3 FURTHER BEDROOMS, FAMILY BATHROOM OUTSIDE GARDENS, PRIVATE PARKING, CENTRAL REAR COURTYARD, BICYCLE STORE, TWO SHEDS Berkhamsted 5.5 miles (London Euston from 30 minutes) A41 Bypass 6.6 miles M1 (Junction 8) 7.5 miles M25 (Junction 20) 8 miles Harpenden 12.5 miles London Luton Airport 12.5 miles London Heathrow Airport 29.3 miles THE PROPERTY A wide, elegant, handcrafted staircase with smooth walnut banister Situated down a private road, opposite a small wood leading onto curls through all three floors of the house adding to the feeling of a glorious open common, Spring House is yet just a half hour train airiness and gracious living. ride from the heart of London. Built in 2012, the house benefits from an array of environmental technologies to create an energy- In the lower ground floor, there is a spacious 23’9 x 17’3 games efficient modern family home. room and a large home office, each flooded with natural light from the glass floors above.T here is also a large shower room, second Understated and elegant from the front, the house opens out utility room, a plant room and three very useful storage rooms. -

Newsletter 59

NEWSLETTER No. 59 JUNE 2010 Berkhamsted Bowmen’s Diamond Anniversary Berkhamsted Bowmen are celebrating the 60 years since the present archery club was formed in 1950; the sporting club is the oldest archery club in Hertfordshire. History of Archery in Berkhamsted Berkhamsted was the favourite home of the Black Prince and the fact that this residence coincided with the peak of the development of the longbow as a weapon of war gives Berkhamsted a special association with archery. Berkhamsted archers were among the victors at the battles of Poitiers, Crécy and Agincourt, and it is reasonable to suppose that many local men were engaged in making and repairing bows and arrows as well as associated equipment. Jones’ ‘History of the Black Prince’ states that in 1347 Robert Le Parker, keeper of the Prince’s Deer Park in Berkhamsted, was ordered ‘to choose in those parts twenty four companion archers, the best he could find, and come with them all speed to Dover’. This order was given when King Edward III and the Black Prince were keeping Christmas at Havering in Essex, and had received news of treachery at Calais. Berkhamsted had an archer called Little John. He was sent by the Black Prince to Chester to collect 1,000 bows, 2,000 sheaves of arrows and 400 gross bowstrings that had been ordered from the bowyers and fletchers of Cheshire and to take them to Plymouth. Little John was paid sixpence a day for his wages and a reasonable sum for carriage. He left Plymouth for Bordeaux on 19th September 1355 and eventually made his way to the battle of Poitiers. -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment

South West Hertfordshire Dacorum Borough Council Three Rivers District Council Watford Borough Council Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment Final Report: Volume 1 October 2008 Tribal Urban Studio Team in association with Atisreal Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose of the study ...........................................................................................1 1.2 Context and study area .......................................................................................1 1.3 Overview of study approach................................................................................5 1.4 Summary of Findings ..........................................................................................7 1.5 Overview of this Report.....................................................................................11 2 Context........................................................................................................................13 2.1 Introduction........................................................................................................13 2.2 Urban Capacity Study .......................................................................................13 2.3 Planning policy ..................................................................................................14 2.4 Population and Household Change ..................................................................17 3 Study -

Pre-Submission Site Allocations Report of Representations Part 1

Pre-Submission Site Allocations Report of Representations Part 1 Contains: Main Report Annex A: Method of Notification Addendum – Focused Changes anges Consultation 2015 January 2016 This publication is Part 1 of the Report of Representations for the Pre-Submission Focused Changes Site Allocations. It contains a summary of the consultation process and discusses the main issues raised. Part 2 comprises Annex B of the Report of Representations: it contains the results of the consultation on the Pre-Submission Focused Changes Site Allocations. Obtaining this information in other formats: If you would like this information in any other language, please contact us. If you would like this information in another format, such as large print or audiotape, please contact us at [email protected] or 01442 228660. CONTENTS Page No. PART 1 1. Introduction 1 2. The Council’s Approach 7 3. Notification and Publicity 9 4. Results 11 5. Summary of the Main Issues 13 6. Sustainability Appraisal (incorporating Strategic Environmental 15 Assessment) 7. Relationship with Local Allocation Master Plans 17 8. Subsequent Meetings and Technical Work 19 9. Changes Proposed 23 ANNEX A: METHOD OF NOTIFICATION Appendices: Appendix 1: Advertisements (comprising formal Notice) 27 Appendix 2: Dacorum Digest article 33 Appendix 3: List of Organisations and Individuals Contacted 35 Appendix 4: Sample Notification Letters 53 Appendix 5: Cabinet Report and Decision - Response to Focused Changes and Submission 56 Appendix 6: Full Council decision 75 PART 2 (see separate document) ANNEX B: RESULTS Table 1: List of Groups / Individuals from whom Representations were received Table 2: Number of Representations considered Table 3: Main Issues raised and Council’s Response Table 4: Schedule of Proposed Changes Table 5: Responses not considered in the Report of Representations (a) List of those making No Comment (b) List of those making comments on the Sustainability Appraisal and Strategic Environmental Assessment 1. -

Volume 2 November 2008 – January 2009 Site Allocations Issues and Options Stage

SUPPLEMENTARY SITE ALLOCATIONS CONSULTATION REPORT ISSUES AND OPTIONS PAPER (NOVEMBER 2008) Volume 2 November 2008 – January 2009 (Issues and Options Stage) Published: July 2013 (based on the position as at 2009) 1 Consultation Reports The Consultation Reports outline steps taken in preparing the Site Allocations Development Plans Document. The responses and information contained in this report is based on the position as at 2009. It covers the nature of the consultations carried out, the means of publicity employed, and the outcomes. The document explains how the Statement of Community Involvement (October 2005) is being implemented, and how the Planning Regulations (and any changes to them) have been taken into account. The Consultation Report is presented in a set of volumes. Volumes currently available are: Volume 1 November 2006 – February 2007 Site Allocations Issues and Options Stage Volume 2 November 2008 – January 2009 Site Allocations Issues and Options Stage Further volumes will be prepared to reflect the Local Development Framework consultation process. 2 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. SUMMARY OF RESPONSES: 5 - Public Consultation 5 - Place Workshops 18 - People Workshops 22 - Citizens’ Panel 22 Appendices: Appendix A: Schedule of Sites Considered 24 Appendix B: List of Housing Sites from the Strategic Housing 35 Land Availability Assessment (November 2008) Appendix C: Public Notices (November 2008) 38 Appendix D: General letter of notification (November 2008) 40 Appendix E: List of organisations contacted 42 Appendix F: Summary of consultation results 45 3 1. INTRODUCTION Purpose of Report 1.1 This report contains the results of the consultation to the Supplementary Site Allocations Issues and Options Paper (November 2008), which was published for comment between 3 November and 19 December 2008. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames