1 Tom Pollock, Montecito Picture Company October 22, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 18 2012 Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma Hosea H. Harvey Temple University, James E. Beasley School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Hosea H. Harvey, Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma, 18 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol18/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, MARKETS, AND HOLLYWOOD'S PERPETUAL ANTITRUST DILEMMA Hosea H. Harvey* This Article focuses on the oft-neglected intersection of racially skewed outcomes and anti-competitive markets. Through historical, contextual, and empirical analysis, the Article describes the state of Hollywood motion-picture distributionfrom its anti- competitive beginnings through the industry's role in creating an anti-competitive, racially divided market at the end of the last century. The Article's evidence suggests that race-based inefficiencies have plagued the film distribution process and such inefficiencies might likely be caused by the anti-competitive structure of the market itself, and not merely by overt or intentional racial-discrimination.After explaining why traditional anti-discrimination laws are ineffective remedies for such inefficiencies, the Article asks whether antitrust remedies and market mechanisms mght provide more robust solutions. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Las Aportaciones Al Cine De Steven Spielberg Son Múltiples, Pero Sobresale Como Director Y Como Productor

Steven Spielberg Las aportaciones al cine de Steven Spielberg son múltiples, pero sobresale como director y como productor. La labor de un productor de cine puede conllevar cierto control sobre las diversas atribuciones de una película, pero a menudo es poco más que aportar el dinero y los medios que la hacen posible sin entrar mucho en los aspectos creativos de la misma como el guión o la dirección. Es por este motivo que no me voy a detener en la tarea de Spielberg como productor más allá de señalar sus dos productoras de cine y algunas de sus producciones o coproducciones a modo de ejemplo, para complementar el vistazo a la enorme influencia de Spielberg en el mundo cinematográfico: En 1981 creó la productora de cine “Amblin Entertainment” junto con Kathleen Kenndy y Frank Marshall. El logo de esta productora pasaría a ser la famosa silueta de la bicicleta con luna llena de fondo de “ET”, la primera producción de la firma dirigida por Spielberg. Otras películas destacadas con participación de esta productora y no dirigidas por Spielberg son “Gremlins”, “Los Goonies”, “Regreso al futuro”, “Esta casa es una ruina”, “Fievel y el nuevo mundo”, “¿Quién engañó a Roger Rabbit?”, “En busca del Valle Encantado”, “Los picapiedra”, “Casper”, “Men in balck”, “Banderas de nuestros padres” & “Cartas desde Iwo Jima” o las series de televisión “Cuentos asombrosos” y “Urgencias” entre muchas otras películas y series. En 1994 fundaría con Jeffrey Katzenberg y David Geffen la productora y distribuidora DreamWorks, que venderían al estudio Viacom en 2006 tras participar en éxitos como “Shrek”, “American Beauty”, “Náufrago”, “Gladiator” o “Una mente maravillosa”. -

The Commuter Production Notes

THE COMMUTER PRODUCTION NOTES RELEASE DATES Australia, New Zealand & Germany (STUDIOCANAL): January 11th 2018 US (Lionsgate): January 12th 2018 UK (STUDIOCANAL): January 19th 2018 France (STUDIOCANAL): January 24th 2018 CONTACTS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Following the worldwide success of Unknown, Non-Stop and Run All Night, star Liam Neeson and director Jaume Collet-Serra reunite for a fourth time with explosive thriller THE COMMUTER about one man‘s frantic quest to prevent disaster on a packed commuter train. The screenplay proved irresistible to both the director and star, not just for the bravura of the action and the thrill of the suspense but for the moral conundrum the protagonist is faced with and the consequences it has on him, the passengers on the train and his family at home. “THE COMMUTER asks the audience, if someone asked you to do something that seems insignifi- cant but you’re not sure of the outcome in exchange for a considerable financial reward, would you do it?” says Jaume Collet-Serra. “That‘s the philosophical choice that our central character - a man of 60 who’s just been fired, has no savings and is mortgaged to the hilt - is faced with. Is he think- ing just about himself or is he going to take into consideration the possible moral consequences of what he’s asked to do? That’s the question we want the audience to ask themselves.” For Neeson, it was also the story’s real-time narrative that gives it a thrilling momentum. -

You Can Find Details of All the Films Currently Selling/Coming to Market in the Screen

1 Introduction We are proud to present the Fís Éireann/Screen Irish screen production activity has more than Ireland-supported 2020 slate of productions. From doubled in the last decade. A great deal has also been comedy to drama to powerful documentaries, we achieved in terms of fostering more diversity within are delighted to support a wide, diverse and highly the industry, but there remains a lot more to do. anticipated slate of stories which we hope will Investment in creative talent remains our priority and captivate audiences in the year ahead. Following focus in everything we do across film, television and an extraordinary period for Irish talent which has animation. We are working closely with government seen Irish stories reach global audiences, gain and other industry partners to further develop our international critical acclaim and awards success, studio infrastructure. We are identifying new partners we will continue to build on these achievements in that will help to build audiences for Irish screen the coming decade. content, in more countries and on more screens. With the broadened remit that Fís Éireann/Screen Through Screen Skills Ireland, our skills development Ireland now represents both on the big and small division, we are playing a strategic leadership role in screen, our slate showcases the breadth and the development of a diverse range of skills for the depth of quality work being brought to life by Irish screen industries in Ireland to meet the anticipated creative talent. From animation, TV drama and demand from the sector. documentaries to short and full-length feature films, there is a wide range of stories to appeal to The power of Irish stories on screen, both at home and all audiences. -

YVONNE BLAKE Costume Designer

(3/18/15) YVONNE BLAKE Costume Designer FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES CAST “THERE BE DRAGONS” Roland Joffe Immi Pictures Wes Bentley Golshifteh Farahani Unax Ugalde “GOYA’S GHOST” Milos Forman The Saul Zaentz Co. Natalie Portman Nomination: Satellite Award Stellan Skarsgard “TIRANTE EL BLANCO” Vicente Aranda Carolina Films (Spain) Giancaro Giannini Future Films (UK) Jane Asher Victoria Abril Leonor Watling Casper Zafer “THE BRIDGE OF SAN LUIS REY Mary McGuckian Pembridge Pictures Robert De Niro Winner: Goya Award for Best Costume Design Kanzaman S.A. Kathy Bates Harvey Keitel “THE RECKONING” Paul McGuigan Renaissance Films Willem Dafoe Paramount Classics Paul Bettany Caroline Wood “CARMEN” Vicente Aranda Star Line Paz Vega Winner: Goya Award for Best Costume Design Leonardo Sbaraglia “JAMES DEAN” Mark Rydell Concourse Prods. James Franco Nomination: Emmy Award for Best Costume Design TNT Michael Moriarty “GAUDI AFTERNOON” Susan Seidelman Lola Films Judy Davis Marcia Gay Harden Juliette Lewis "PRESENCE OF MIND" Antonio Aloy Presence of Mind, LLC. Lauren Bacall Sadie Frost Harvey Keitel "WHAT DREAMS MAY COME" Vincent Ward Interscope/Polygram Robin Williams Barnet Bain Annabella Sciorra Stephen Simon Cuba Gooding, Jr. "CRIME OF THE CENTURY" Mark Rydell HBO Stephen Rea Barbara Broccoli Isabella Rossellini "LOOKING FOR RICHARD" Al Pacino Fox Searchlight Al Pacino (Battle sequences) Kevin Spacey "COMPANY BUSINESS" Nicholas Myer Pathe Screen Ent. Gene Hackman Mikhail Baryshnikov (cont.) SANDRA MARSH & ASSOCIATES Tel: (310) 285-0303 Fax: -

Steven Spielberg's Early Career As a Television Director at Universal Studios

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Surugadai University Academic Information Repository Steven Spielberg's Early Career as a Television Director at Universal Studios 著者名(英) Tomohiro Shimahara journal or 駿河台大学論叢 publication title number 51 page range 47-61 year 2016-01 URL http://doi.org/10.15004/00001463 Steven Spielberg’s Early Career as a Television Director at Universal Studios SHIMAHARA Tomohiro Introduction Steven Spielberg (1946-) is one of the greatest movie directors and producers in the history of motion picture. In his four-decade career, Spielberg has been admired for making blockbusters such as Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), E.T.: the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Indiana Jones series (1981, 1984, 1989, 2008), Schindler’s List (1993), Jurassic Park series (1993, 1997, 2001, 2015), Saving Private Ryan (1998), Lincoln (2012) and many other smash hits. Spielberg’s life as a filmmaker has been so brilliant that it looks like no one believes that there was any moment he spent at the bottom of the ladder in the movie industry. Much to the surprise of the skeptics, Spielberg was once just another director at Universal Television for the first couple years after launching himself into the cinema making world. Learning how to make good movies by trial and error, Spielberg made a breakthrough with his second feature-length telefilm Duel (1971) at the age of 25 and advanced into the big screen, where he would direct and produce more than 100 movies, including many great hits and some commercial or critical failures, in the next 40-something years. -

Julianne Moore Liam Neeson Amanda Seyfried

JULIANNE MOORE LIAM NEESON AMANDA SEYFRIED in Directed by Atom Egoyan Screenplay by Erin Cressida Wilson CHLOE is fully financed by France‘s StudioCanal and developed by Montecito Picture Company, co-founded by Ivan Reitman and Tom Pollock. Ivan Reitman, Joe Medjuck and Jeffrey Clifford are producers for Montecito. Co-producers are Simone Urdl and Jennifer Weiss. Executive Producers are Tom Pollock along with Jason Reitman, Daniel Dubiecki, and Ron Halpern. CHLOE will be distributed by StudioCanal in France and in the United Kingdom and Germany through its subsidiaries Optimum Releasing and Kinowelt. It will also handle worldwide sales outside its direct distribution territories. The Cast Catherine Stewart JULIANNE MOORE David Stewart LIAM NEESON Chloe AMANDA SEYFRIED Michael Stewart MAX THIERIOT Frank R.H. THOMSON Anna NINA DOBREV Receptionist MISHU VELLANI Bimsy JULIE KHANER Alicia LAURA DE CARTERET Eliza NATALIE LISINSKA Trina TIFFANY KNIGHT Miranda MEGHAN HEFFERN Party Guest ARLENE DUNCAN Another Girl KATHY MALONEY Maria ROSALBA MARTINNI Waitress TAMSEN McDONOUGH Waitress 2 KATHRYN KRIITMAA Bartender ADAM WAXMAN Young Co-Ed KRYSTA CARTER Nurse SEVERN THOMPSON ‗Orals‘ Student SARAH CASSELMAN Boy DAVID REALE Boy 2 MILTON BARNES Woman Behind Bar KYLA TINGLEY Chloe‘s Client #1 SEAN ORR Chloe‘s Client #2 PAUL ESSIEMBRE Chloe‘s Client #3 ROD WILSON Stunt Hockey Player RILEY JONES • CHLOE 2 The Filmmakers Director ATOM EGOYAN Writer ERIN CRESSIDA WILSON Produced by IVAN REITMAN Producers JOE MEDJUCK JEFFREY CLIFFORD Co-Producers SIMONE URDL JENNIFER WEISS Executive Producers JASON REITMAN DANIEL DUBIECKI THOMAS P. POLLOCK RON HALPERN Associate Producers ALI BELL ERIN CRESSIDA WILSON Production Manager STEPHEN TRAYNOR Director of Photography PAUL SAROSSY Production Designer PHILLIP BARKER Editor SUSAN SHIPTON Music MYCHAEL DANNA Costumes DEBRA HANSON Casting JOANNA COLBERT (US) RICHARD MENTO (US) JOHN BUCHAN (Canada) JASON KNIGHT (Canada) Camera Operator PAUL SAROSSY First Assistant Director DANIEL J. -

STUNT CONTACT BREAKDOWN SERVICE 1-11-2017 8581 SANTA MONICA BLVD #143, WEST HOLLYWOOD, CA 90069 - TEL: 323-951-1500 Page 1 of 48

STUNT CONTACT BREAKDOWN SERVICE 1-11-2017 8581 SANTA MONICA BLVD #143, WEST HOLLYWOOD, CA 90069 - TEL: 323-951-1500 Page 1 of 48 STUNT CONTACT ACTION BREAKDOWN SERVICE FOR STUNT PROFESSIONALS 1-11-2017 (323) 951-1500 WWW.STUNTCONTACT.COM 2017. Stunt Contact is provided under a single license and is for personal use only. Any sharing or commercial redistribution of information contained herein is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of the Editor and will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. SHOW TITLE: UNDERWATER FEATURE** PRODUCTION COMPANY: CHERNIN ENTERTAINMENT / TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORP ADDRESS: UNDERWATER - PROD OFFICE FOX LOUSIANA PRODUCTIONS LLC 8301 W JUDGE PEREZ DR SUITE 302 CHALMETTE, LA 70043 ATTN: MARK RAYNER, STUNT COORDINATOR [email protected] TEL: 504-595-1710 PRODUCER: PETER CHERNIN, TONIA DAVIS, JENNO TOPPING WRITER: BRIAN DUFFIELD DIRECTOR: WILLIAM EUBANK LOCATION: NEW ORLEANS SHOOTS: 3/6/2017 SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS: AQUATIC THRILLER WILL BE HELMED BY “THE SIGNAL” DIRECTOR, WILLIAM EUBANK. AFTER AN EARTHQUAKE DESTROYS THEIR UNDERWATER STATION, A CREW OF SIX MUST NAVIGATE TWO MILES IN THE DANGEROUS UNKNOWN DEPTHS OF THE OCEAN FLOOR TO MAKE IT TO SAFETY. SCRIPT WAS ON THE 2015 HIT LIST. VERY EARLY. PROJ IS STILL IN CASTING - NOT CERTAIN OF DOUBLE REQUIREMENTS. LOCAL HIRES MAY SUBMIT NOW BY EMAIL ONLY. SHOOTS THRU MID-MAY. SHOW TITLE: KNUCKLEBALL FEATURE** PRODUCTION COMPANY: THE UMBRELLA COLLECTIVE / 775 MEDIA ADDRESS: KUCKLEBALL - PROD OFFICE 2003090 ALBERTA LTD 1 To subscribe go to: www.stuntcontact.com STUNT CONTACT BREAKDOWN SERVICE 1-11-2017 8581 SANTA MONICA BLVD #143, WEST HOLLYWOOD, CA 90069 - TEL: 323-951-1500 Page 2 of 48 123 CREE ROAD SHERWOOD PARK, AB T8A 3X9 ATTN: RON WEBBER, STUNT COORDINATOR [email protected] 587-328-0288 PRODUCER: KURTIS DAVID HARDER, LARS LEHMAN, JULIAN BLACK ANTELOPE WRITER: KEVIN COCKLE, MICHAEL PETERSON DIRECTOR: MICHAEL PETERSON LOCATION: EDMONTON, AB CAST: MICHAEL IRONSIDE SHOOTS: 1/16/2017 - TENT SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS: HORROR THRILLER. -

Al Cinema Dal 12 Marzo

Presenta CHLOE Diretto da ATOM EGOYAN Sceneggiatura di ERIC CRESSIDA WILSON Con JULIANNE MOORE LIAM NEESON AMANDA SEYFRIED I materiali sono scaricabili dall’ area stampa di www.eaglepictures.com Visita anche www.chloeilfilm.it Durata 96’ AL CINEMA DAL 12 MARZO Ufficio Stampa: Marianna Giorgi [email protected] Cast Artistico Catherine Stewart JULIANNE MOORE David Stewart LIAM NEESON Chloe AMANDA SEYFRIED Michael Stewart MAX THIERIOT Frank R.H. THOMSON Anna NINA DOBREV Reception MISHU VELLANI Bimsy JULIE KHANER Alicia LAURA DE CARTERET Eliza NATALIE LISINSKA Trina TIFFANY KNIGHT Miranda MEGHAN HEFFERN Ospite festa ARLENE DUNCAN Altra ragazza KATHY MALONEY Maria ROSALBA MARTINNI Cameriera TAMSEN McDONOUGH Cameriera 2 KATHRYN KRIITMAA Barman ADAM WAXMAN Giovane Co-Ed KRYSTA CARTER Infermiere SEVERN THOMPSON Studente Oral SARAH CASSELMAN Ragazzo DAVID REALE Ragazzo 2 MILTON BARNES Donna barista KYLA TINGLEY Cliente Chloe SEAN ORR Cliente Chloe2 PAUL ESSIEMBRE Cliente Chloe 3 ROD WILSON Stunt Giocatore Hockey RILEY JONES Cast Tecnico Regista ATOM EGOYAN Sceneggiatore ERIN CRESSIDA WILSON Prodotto da IVAN REITMAN Produttori JOE MEDJUCK JEFFREY CLIFFORD Co-produttuori SIMONE URDL JENNIFER WEISS Produttori esecutivi JASON REITMAN DANIEL DUBIECKI THOMAS P. POLLOCK RON HALPERN Produttori associati ALI BELL ERIN CRESSIDA WILSON Direttore di produzione STEPHEN TRAYNOR Direttore della fotografia PAUL SAROSSY Scenografo PHILLIP BARKER Montatore SUSAN SHIPTON Musiche MYCHAEL DANNA Costumi DEBRA HANSON Casting JOANNA COLBERT (US) RICHARD MENTO (US) JOHN BUCHAN (Canada) JASON KNIGHT (Canada) Operatore PAUL SAROSSY Primo aiuto regista DANIEL J. MURPHY Suono BISSA SCEKIC Supervisore sceneggiatura JILL CARTER Attrezzista CRAIG GRANT Elettricista BOB DAVIDSON Macchinista CHRIS FAULKNER Location Manager EARDLEY WILMOT Breve sinossi CHLOE è una storia di amore, di suspense e tradimenti. -

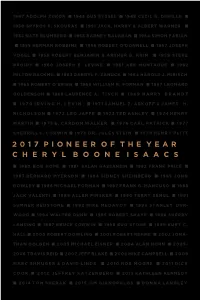

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner.