Memphis Heritage Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

418GBJ Web.Pdf

April 2018 Volume 23, Number 6 From the Executive GEORGIA BAR Director: Website and Directory Enhancements to Benefit Bar Members and the Public Financial Institutions: JOURNAL Protecting Elderly Clients From Financial Exploitation Bending the Arc: Georgia Lawyers in the Pursuit of Social Justice Writing Matters: What e-Filing May Mean to Your Writing 2018 ANNUAL MEETING Amelia Island, Fla. | June 7-10 GEORGIA LAWYERS HELPING LAWYERS Georgia Lawyers Helping Lawyers (LHL) is a new confidential peer-to-peer program that will provide u colleagues who are suffering from stress, depression, addiction or other personal issues in their lives, with a fellow Bar member to be there, listen and help. The program is seeking not only peer volunteers who have experienced particular mental health or substance use u issues, but also those who have experience helping others or just have an interest in extending a helping hand. For more information, visit: www.GeorgiaLHL.org ADMINISTERED BY: DO YOUR EMPLOYEE BENEFITS ADD UP? Finding the right benets provider doesn’t have to be a calculated risk. Our oerings range from Health Coverage to Disability and everything in between. Through us, your rm will have access to unique cost savings opportunities, enrollment technology, HR Tools, and more! The Private Insurance Exchange + Your Firm = Success START SHOPPING THE PRIVATE INSURANCE EXCHANGE TODAY! www.memberbenets.com/gabar OR CALL (800) 282-8626 APRIL 2018 HEADQUARTERS COASTAL GEORGIA OFFICE SOUTH GEORGIA OFFICE 104 Marietta St. NW, Suite 100 18 E. Bay St. 244 E. Second St. (31794) Atlanta, GA 30303 Savannah, GA 31401-1225 P.O. -

A History Lesson: Reparations for What?

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2003 A History Lesson: Reparations for What? Emma Coleman Jordan Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/102 58 N.Y.U. Ann. Surv. Am. L. 557-613 (2003) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Society Commons, and the Litigation Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications January 2010 A History Lesson: Reparations for What? 58 N.Y.U. Ann. Surv. Am. L. 557-613 (2003) Emma Coleman Jordan Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/102/ Posted with permission of the author A HISTORY LESSON: REPARATIONS FOR WHAT? EMMA COLEMAN jORDAN* A major difficulty facing the reparations-for-slavery movement is that to date the movement has focused its litigation strategies and its rhetorical effort upon the institution of slavery. While slavery is the root of modern racism, it suffers many defects as the center piece of a reparations litigation strategy. The most important diffi culty is temporal. Formal slavery ended in 1865. Thus, the time line of potentially reparable injury extends to well before the pe riod of any person now living. The temporal difficulty arises from the conventional expectations of civil litigation, which require a harmony of identity between the defendants and the plaintiffs. -

An Assessment of Adult Basic Education in Shelby County, Tennessee

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 097 537 CE 002 308 AUTHOR Jordan, Jimmie L. TITLE An Assessment of Adult Basic Education in Shelby County, Tennessee. INSTITUTION Shelby County Board of Education, Memphis,Tenn. PUB DATE . Dec 73 NOTE 63p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Adult Basic Education; Data Collection; Educational Attitudes; Educational Research; *Program Attitudes; *Program Evaluation; Questionnaires; Student Attitudes; Student Teacher Relationship; Surveys; Teacher Attitudes IDENTIFIERS *Tennessee ABSTRACT This report of an exploratory study of Adult Basic Education (ABE) gives a brief summary of backgroundand methodology and represents findings about students and teachers in ShelbyCounty, Tennessee. For the students 41 findings are reported relLtingto age, sex, race, marital status, years of schooling completed., employment, income, life style, reasons for enrollment, problems,and reactions to the program. For the teachers 65 findingsare reported relating to age, sex, race, education, teaching experience, experience with and reactions to the ABE program, and their feelingsas to the areas in which the program was successful in helping the students.Problems encountered in conducting the study made drawing conclusions difficult. Comments are offered with respectto several ways of improving the conduct of future studies; improvingstudent-teacher relationships; assistance for teachers, both preserviceand on-the-job; a followup of dropouts; and vocational choicesof students. The results of the student and teacher questionnairesare -

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Final November 2005 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Summary Statement 1 Bac.ground and Purpose 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 National Persp4l<live 5 1'k"Y v. f~u,on' World War I: 1896-1917 5 World W~r I and Postw~r ( r.: 1!1t7' EarIV 1920,; 8 Tulsa RaCR Riot 14 IIa<kground 14 TI\oe R~~ Riot 18 AIt. rmath 29 Socilot Political, lind Economic Impa<tsJRamlt;catlon, 32 INVENTORY 39 Survey Arf!a 39 Historic Greenwood Area 39 Anla Oubi" of HiOlorK G_nwood 40 The Tulsa Race Riot Maps 43 Slirvey Area Historic Resources 43 HI STORIC GREENWOOD AREA RESOURCeS 7J EVALUATION Of NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 91 Criteria for National Significance 91 Nalional Signifiunce EV;1lu;1tio.n 92 NMiol\ill Sionlflcao<e An.aIYS;s 92 Inl~ri ly E~alualion AnalY'is 95 {"",Iu,ion 98 Potenl l~1 M~na~menl Strategies for Resource Prote<tion 99 PREPARERS AND CONSULTANTS 103 BIBUOGRAPHY 105 APPENDIX A, Inventory of Elltant Cultural Resoun:es Associated with 1921 Tulsa Race Riot That Are Located Outside of Historic Greenwood Area 109 Maps 49 The African American S«tion. 1921 51 TI\oe Seed. of c..taotrophe 53 T.... Riot Erupt! SS ~I,.,t Blood 57 NiOhl Fiohlino 59 rM Inva.ion 01 iliad. TIll ... 61 TM fighl for Standp''''' Hill 63 W.II of fire 65 Arri~.. , of the Statl! Troop< 6 7 Fil'lal FiOlrtino ~nd M~,,;~I I.IIw 69 jii INTRODUCTION Summary Statement n~sed in its history. -

SUN STUDIO Inspelningsteknik Och Sound

Högskoleexamen SUN STUDIO Inspelningsteknik och sound Författare: Jacob Montén Handledare: Karin Eriksson Examinator: Karin Larsson Eriksson Termin: HT 2019 Ämne: Musikvetenskap Nivå: Högskoleexamen Kurskod: 1MV706 Abstrakt Detta är en uppsats som handlar om Sun Studio under 1950 talet i USA, hur studion kom till och om dess grundare Sam Phillips och de tekniska tillgångarna och begränsningar som skapade ”soundet” för Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ike Turner och många fler. Sam Phillips producerade många tidlösa inspelningar med ljudkaraktäristiska egenskaper som eftertraktas än idag. Med hjälp av litteratur-, ljud- och bildanalys beskriver jag hur musikern och producenten bakom musiken skapade det så kallade ”Sun Soundet”. Ett uppvaknande i musikvärlden för den afroamerikanska musiken hade skett och ingen skulle få hindra Phillips från att göra den hörd. För att besvara mina frågeställningar har texter, tidigare forskning och videomaterial analyserats. Genom den hermeneutiska metoden har intervjumaterial och dokumentärer varit en viktig källa i denna studie. Nyckelord Sun Records, Sam Phillips, Slapback Echo, Soundet, Sun Studio, Analog Tack Stort tack till min handledare Karin Eriksson för den feedback och stöd jag har fått under arbetets gång. Tack till min familj för er uppmuntran och tålamod. Innehållsförteckning Innehållsförteckning.................................................................................................................1 1.Inledning...............................................................................................................................2 -

Broadcasting Telecasting

YEAR 101RN NOSI1)6 COLLEIih 26TH LIBRARY énoux CITY IOWA BROADCASTING TELECASTING THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF RADIO AND TELEVISION APRIL 1, 1957 350 PER COPY c < .$'- Ki Ti3dddSIA3N Military zeros in on vhf channels 2 -6 Page 31 e&ol 9 A3I3 It's time to talk money with ASCAP again Page 42 'mars :.IE.iC! I ri Government sues Loew's for block booking Page 46 a2aTioO aFiE$r:i:;ao3 NARTB previews: What's on tap in Chicago Page 79 P N PO NT POW E R GETS BEST R E SULTS Radio Station W -I -T -H "pin point power" is tailor -made to blanket Baltimore's 15 -mile radius at low, low rates -with no waste coverage. W -I -T -H reaches 74% * of all Baltimore homes every week -delivers more listeners per dollar than any competitor. That's why we have twice as many advertisers as any competitor. That's why we're sure to hit the sales "bull's -eye" for you, too. 'Cumulative Pulse Audience Survey Buy Tom Tinsley President R. C. Embry Vice Pres. C O I N I F I I D E I N I C E National Representatives: Select Station Representatives in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington. Forloe & Co. in Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta. RELAX and PLAY on a Remleee4#01%,/ You fly to Bermuda In less than 4 hours! FACELIFT FOR STATION WHTN-TV rebuilding to keep pace with the increasing importance of Central Ohio Valley . expanding to serve the needs of America's fastest growing industrial area better! Draw on this Powerhouse When OPERATION 'FACELIFT is completed this Spring, Station WNTN -TV's 316,000 watts will pour out of an antenna of Facts for your Slogan: 1000 feet above the average terrain! This means . -

Broadway: Les Misérables (Grantaire/Bamatabois, U/S Javert, U/S Thénardier)

GGLAM – Cast Bios Updated: 08.03.15 JOHN RAPSON (The D’Ysquith Family). Broadway: Les Misérables (Grantaire/Bamatabois, u/s Javert, u/s Thénardier). Tour and Regional: Les Misérables, Disney On Classic (with the Tokyo Philharmonic), Sweeney Todd, Brigadoon. BFA, University of Michigan. Infinite love and thanks to Mom, Dad, Alex, Stella, Chris and the gents of CGF, the family dinner crew, and the utterly extraordinary Gent’s Guide team. Humbled and honored to be part of this brilliant piece. Now and then pigs CAN fly. This one’s for Pat. KEVIN MASSEY (Monty Navarro). Broadway: Gentleman's Guide, Memphis (u/s Huey), Tarzan (u/s Tarzan), Deaf West’s Big River, NYCO’s Antony & Cleopatra (Eros), originated Almanzo in Little House...Prairie (1st Nat., Paper Mill, Guthrie) and D’Artagnan in Three Musketeers (Chicago Shakespeare). Europe: Tarzan (Tarzan), Grease! (Doody). Regional: Asolo Rep’s Bonnie & Clyde (Ted), Utah Shakes’ & Kansas City Rep’s Pippin (Pippin), Skylight Music Theater's Les Mis (Marius), MUNY’s Footloose (Willard). UNC, Morehead-Cain Scholar. Proud husband to Kara Lindsay! Love to my family. @kcmassey1 kevinmassey.com KRISTEN BETH WILLIAMS (Sibella Hallward) is delighted to join this deliciously devilish company! West End: Top Hat (Dale Tremont). Broadway: Pippin; Nice Work...; Anything Goes; Promises, Promises. Other NYC: The Marvelous Wonderettes (Off-Bway), Encores!, appearances at Town Hall and Carnegie Hall. Regional: Big Fish (Sandra, Alpine Theatre Project), White Christmas (Betty Haynes, Ordway), Music Theatre of Wichita, Ogunquit, Paper Mill, to name a few. Love & thanks to Dustin, Jason, Jay, and Darko, to "The Fam" always, and to Jimmy-my home. -

Keith Hess Appointed Vice President and Managing Director of the Guest House at Graceland

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: THE BECKWITH COMPANY David Beckwith | 323-845-9836 [email protected] Marjory Hawkins | (512) 838-6324 [email protected] KEITH HESS APPOINTED VICE PRESIDENT AND MANAGING DIRECTOR OF THE GUEST HOUSE AT GRACELAND MEMPHIS, Tenn. – February 17, 2016 – Hotel industry veteran Keith Hess has been appointed vice president and managing director of the under-construction, full-service, 450-room resort hotel, The Guest House at Graceland, which is located just steps away from Elvis Presley’s Graceland® in Memphis. The announcement was made by Jim Dina, chief operating officer of the Pyramid Hotel Group, which is managing the hotel for Elvis Presley Enterprises/Graceland. Hess brings more than 30 years of hotel and resort experience. For the past seven years, he has served as Pyramid Hotel Group’s vice president of operations, overseeing hotel and resort teams with Hilton, Hyatt, Westin, Sheraton, Marriott as well as Independent Brands. “All of us at Pyramid look forward to being part of this unprecedented, world-class resort and conference destination in the heart of Graceland,” said Dina. “We are pleased to announce Keith Hess as the managing director of The Guest House at Graceland. He is a strong leader, with a talent for cultivating and building top-notch hotel teams.” “Graceland is delighted to have Keith join us in such a key role at The Guest House at Graceland,” said Jack Soden, CEO of Elvis Presley Enterprises. “The Guest House is our most exciting project since opening Graceland in 1982, and we know that with Keith and Pyramid’s invaluable support, we’ll be providing extraordinary guest, conference, meeting and event experiences for the Memphis community and Graceland visitors from around the world.” The Guest House at Graceland is scheduled to open on October 27 of this year with a three-day gala grand opening celebration. -

Camper Guidebook 2009.Indd

Delta Girls Rock Camp Guidebook Delta Girls Rock Camp Guidebook CAMP SCHEDULE Monday, July 27, 2009 – Friday, July 31, 2009 8:30 -9:00 Registration Dobbs Commons 9:00 – 9:15 Morning Kick Off Chapel Morning Performers To open your mind and see the world through a different lens. To open yourself to change and discovery. 9:20-11:30 Instrument Instruction Dobbs Center* To open your potential. 11:30-12:00 Lunch Dining Hall Since its inception in 2004, Hutchison’s Arts Academy’s mission 12:10-12:45 Lunchbox Series LIVE! Wiener Theater has been to awaken the unique creative voice in each student to steer them toward a lifelong path of artistic enrichment and cre- 1:00- 2:00 Songwriting/Herstory Workshop Wiener Theater/ ative growth. (M, W, F) Labry Hall 1:00- 2:00 DIY Arts and Crafts Workshop Dobbs Center* A focus on the arts is central to our school which is dedicated to (T, Th) the parallel growth of mind, body, and spirit as it educates young women for success in college and for lives of integrity and respon- 2:00-5:00 Band Practice Dobbs Center* sible citizenship. 5:00-5:15 Afternoon Wrap-Up I am delighted to welcome you to the Delta Girls Rock Camp ex- Equipment Inventory perience, part of the Center’s Mary Miles Loveless Arts Academy. 5:15-5:30 Camper Pick Up Welcome to Hutchison’s campus. I hope this enriching week helps you hone your unique creative voice! Please let the Center for 5:30-6:30 Graduation & Reception Dining Hall Excellence staff and Rock Camp directors know how we can make (Friday) this the best week of your summer. -

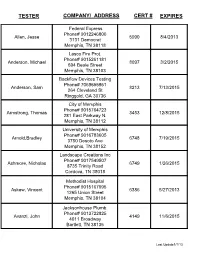

Tester Company/ Address Cert # Expires

TESTER COMPANY/ ADDRESS CERT # EXPIRES Federal Express Phone# 9012246800 Allen, Jesse 5990 8/4/2013 3131 Democrat Memphis, TN 38118 Lasco Fire Prot. Phone# 9015261181 Anderson, Michael 8097 3/2/2015 694 Beale Street Memphis, TN 38103 Backflow Devices Testing Phone# 7069655951 Anderson, Sam 8213 7/13/2015 264 Cleveland St Ringgold, GA 30736 City of Memphis Phone# 9015764723 Armstrong, Thomas 3453 12/8/2015 281 East Parkway N. Memphis, TN 38112 University of Memphis Phone# 9016783605 Arnold,Bradley 6748 7/19/2015 3750 Desoto Ave Memphis, TN 38152 Landscape Creations Inc Phone# 9017549507 Ashmore, Nicholas 6749 1/26/2015 8735 Trinity Road Cordova, TN 38018 Methodist Hospital Phone# 9015167095 Askew, Vincent 6386 5/27/2013 1265 Union Street Memphis, TN 38104 Jacksonhouse Plumb. Phone# 9013722825 Avanzi, John 4149 11/6/2015 4011 Broadway Bartlett, TN 38135 Last Update1/1/13 TESTER COMPANY/ ADDRESS CERT # EXPIRES Upchurch Services Phone# 9013880333 Avanzi, Steve 2941 6/12/2015 1792 Dancy Boulevard Horn Lake, MS 38637 Shelby Co. Codes Phone# 9013794340 Bain, Barry 7728 3/16/2014 6465 Mullins Station Memphis, TN 38134 Autozone Phone# 9014956563 Baker, David A. 6881 11/16/2014 123 S. Front Street Memphis, TN 38103 Trip Trezevant Inc Phone# 9017535900 Baker, Michael 8285 9/27/2015 7092 Poplar Ave Germantown, TN 38138 Tim Baker Plumbing Phone# 9015531524 Baker, Timothy 9160 Highway 64, Ste12, 4303 1/21/2013 #152 Lakeland, TN 38002 City of Germantown Phone# 9017577260 Bales, Dennis W. 8015 1/13/2015 7700 Southern Ave Germantown, TN 38138 Memphis LG&W Phone# 9015287757 Baxter, Felicia 7397 2/12/2013 220 S. -

RCA/Legacy Set to Release Elvis Presley - a Boy from Tupelo: the Complete 1953-1955 Recordings on Friday, July 28

RCA/Legacy Set to Release Elvis Presley - A Boy From Tupelo: The Complete 1953-1955 Recordings on Friday, July 28 Most Comprehensive Early Elvis Library Ever Assembled, 3CD (Physical or Digital) Set Includes Every Known Sun Records Master and Outtake, Live Performances, Radio Recordings, Elvis' Self-Financed First Acetates, A Newly Discovered Previously Unreleased Recording and More Deluxe Package Includes 120-page Book Featuring Many Rare Photos & Memorabilia, Detailed Calendar and Essays Tracking Elvis in 1954-1955 A Boy From Tupelo - The Complete 1953-55 Recordings is produced, researched and written by Ernst Mikael Jørgensen. Elvis Presley - A Boy From Tupelo: The Sun Masters To Be Released on 12" Vinyl Single Disc # # # # # Legacy Recordings, the catalog division of Sony Music Entertainment, and RCA Records will release Elvis Presley - A Boy From Tupelo - The Complete 1953-1955 Recordings on Friday, July 28. Available as a 3CD deluxe box set and a digital collection, A Boy From Tupelo - The Complete 1953-1955 Recordings is the most comprehensive collection of early Elvis recordings ever assembled, with many tracks becoming available for the first time as part of this package and one performance--a newly discovered recording of "I Forgot To Remember To Forget" (from the Louisiana Hayride, Shreveport, Louisiana, October 29, 1955)--being officially released for the first time ever. A Boy From Tupelo – The Complete 1953-1955 Recordings includes--for the first time in one collection--every known Elvis Presley Sun Records master and outtake, plus the mythical Memphis Recording Service Acetates--"My Happiness"/"That's When Your Heartaches Begin" (recorded July 1953) and "I'll Never Stand in Your Way"/"It Wouldn't Be the Same (Without You)" (recorded January 4, 1954)--the four songs Elvis paid his own money to record before signing with Sun. -

Six Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello

McCoy Theatre Rhodes College presents Music by: Book adapted from Voltaire by: Lyrics by: Leornard Bernstein Hugh Wheeler Richard Wilbur Six Characters In Search Of An Author by Luigi Pirandello Season 10 McCoy Theatre Rhodes College presents Six Characters In Search Of An Author by Luigi Pirandello Directed by Elfin Frederick Vogel McCoy Visiting Artist Guest Director Assistant Director Misty Wakeland Technical Director Steve Jones Set Designer Steve Jones Lighting Designer Kristina Kloss Costume Designer David Jilg Assistant Costumer Charlotte Higginbotham Stage Manager Tracy Castleberry Assistant Stage Manager Louise Casini produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. 7 Six Characters in Search of an Author Cast Father ..............................................................Albert Hoagbarth Mother ..................................................................... Dina Facklis Stepdaughter ................................................... Catherine Eckman Son ...................................................................... Eric Underdahl Madame Pace ...................................................... Kimberly Groat Little Girl .................................................................Alison Kamhi Little Boy .....................................................................Tim Olcott Director .......................................................................Chris Hall Lead Actor........ .......................................................John Nichols Lead Actress .........................................................