Mobile Banking and Payments Security What Banks and Payment Service Providers Need to Know to Keep Their Customers Safe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Industry Perspectives on Mobile/Digital Wallets and Channel Convergence

Mobile Payments Industry Workgroup (MPIW) December 3-4, 2014 Meeting Report Industry Perspectives on Mobile/Digital Wallets and Channel Convergence Elisa Tavilla Payment Strategies Industry Specialist Federal Reserve Bank of Boston March 2015 The author would like to thank the speakers at the December meeting and the members of the MPIW for their thoughtful comments and review of the report. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, or the Federal Reserve System. I. Introduction The Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and Atlanta1 convened a meeting of the Mobile Payments Industry Workgroup (MPIW) on December 3-4, 2014 to discuss (1) different wallet platforms; (2) how card networks and other payment service providers manage risks associated with converging digital and mobile channels; and (3) merchant strategies around building a mobile payment and shopping experience. Panelists considered how the mobile experience is converging with ecommerce and what new risks are emerging. They discussed how EMV,2 tokenization,3 and card-not-present (CNP)4 will impact mobile/digital wallets and shared their perspectives on how to overcome risk challenges in this environment, whether through tokenization, encryption, or the use of 3D Secure.5 MPIW members also discussed how various tokenization models can be supported in the digital environment, and the pros and cons of in-app solutions from both a merchant and consumer perspective. With the broad range of technologies available in the marketplace, merchants shared perspectives on how to address the emergence of multiple wallets and the expansion of mobile/digital commerce. -

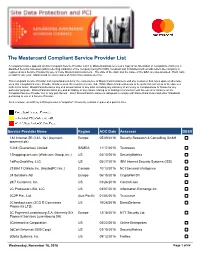

The Mastercard Compliant Service Provider List

The Mastercard Compliant Service Provider List A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) MasterCard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) MasterCard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more MasterCard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. MasterCard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of MasterCard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While MasterCard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, MasterCard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. MasterCard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each MasterCard Customer is obligated to comply with MasterCard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/09/2016 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Link (Guarantee) Limited SAMEA 11/17/2015 Trustwave 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/13/2016 SecurityMetrics 1stPayGateWay, LLC US 05/27/2016 IBM Internet Security Systems (ISS) 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

2016 8Th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Cyber Power

2016 8th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Cyber Power N.Pissanidis, H.Rõigas, M.Veenendaal (Eds.) 31 MAY - 03 JUNE 2016, TALLINN, ESTONIA 2016 8TH International ConFerence on CYBER ConFlict: CYBER POWER Copyright © 2016 by NATO CCD COE Publications. All rights reserved. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1626N-PRT ISBN (print): 978-9949-9544-8-3 ISBN (pdf): 978-9949-9544-9-0 CopyriGHT AND Reprint Permissions No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence ([email protected]). This restriction does not apply to making digital or hard copies of this publication for internal use within NATO, and for personal or educational use when for non-profit or non-commercial purposes, providing that copies bear this notice and a full citation on the first page as follows: [Article author(s)], [full article title] 2016 8th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Cyber Power N.Pissanidis, H.Rõigas, M.Veenendaal (Eds.) 2016 © NATO CCD COE Publications PrinteD copies OF THIS PUBlication are availaBLE From: NATO CCD COE Publications Filtri tee 12, 10132 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 717 6800 Fax: +372 717 6308 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ccdcoe.org Head of publishing: Jaanika Rannu Layout: Jaakko Matsalu LEGAL NOTICE: This publication contains opinions of the respective authors only. They do not necessarily reflect the policy or the opinion of NATO CCD COE, NATO, or any agency or any government. -

Introducing Linux on IBM Z Systems IT Simplicity with an Enterprise Grade Linux Platform

Introducing Linux on IBM z Systems IT simplicity with an enterprise grade Linux platform Wilhelm Mild IBM Executive IT Architect for Mobile, z Systems and Linux © 2016 IBM Corporation IBM Germany What is Linux? . Linux is an operating system – Operating systems are tools which enable computers to function as multi-user, multitasking, and multiprocessing servers. – Linux is typically delivered in a Distribution with many useful tools and Open Source components. Linux is hardware agnostic by design – Linux runs on multiple hardware architectures which means Linux skills are platform independent. Linux is modular and built to coexist with other operating systems – Businesses are using Linux today. More and more businesses proceed with an evolutionary solution strategy based on Linux. 2 © 2016 IBM Corporation What is IBM z Systems ? . IBM z Systems is the family name used by IBM for its mainframe computers – The z Systems families were named for their availability – z stands for zero downtime. The systems are built with spare components capable of hot failovers to ensure continuous operations. IBM z Systems paradigm – The IBM z Systems family maintains full backward compatibility. In effect, current systems are the direct, lineal descendants of System/360, built in 1964, and the System/370 from the 1970s. Many applications written for these systems can still run unmodified on the newest z Systems over five decades later. IBM z Systems variety of Operating Systems – There are different traditional Operating Systems that run on z Systems like z/OS, z/VSE or TPF. With z/VM IBM delivers a mature Hypervisor to virtualize the operating systems. -

Online Banking Customer Awareness and Education Program

Online Banking Customer Awareness and Education Program Online Banking Customer Awareness and Education Program Rev. 6/21 Table of Contents Online Banking Customer Awareness and Education Program Overview ............................................................... 1 Unsolicited Contact .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Luther Burbank Savings Contact Information ................................................................................................................... 1 Online Banking Security Certification .................................................................................................................................. 1 Email Security............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Malicious Emails ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Email Attachments .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Verify Emails .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Strong and Complex -

How Mpos Helps Food Trucks Keep up with Modern Customers

FEBRUARY 2019 How mPOS Helps Food Trucks Keep Up With Modern Customers How mPOS solutions Fiserv to acquire First Data How mPOS helps drive food truck supermarkets compete (News and Trends) vendors’ businesses (Deep Dive) 7 (Feature Story) 11 16 mPOS Tracker™ © 2019 PYMNTS.com All Rights Reserved TABLEOFCONTENTS 03 07 11 What’s Inside Feature Story News and Trends Customers demand smooth cross- Nhon Ma, co-founder and co-owner The latest mPOS industry headlines channel experiences, providers of Belgian waffle company Zinneken’s, push mPOS solutions in cash-scarce and Frank Sacchetti, CEO of Frosty Ice societies and First Data will be Cream, discuss the mPOS features that acquired power their food truck operations 16 23 181 Deep Dive Scorecard About Faced with fierce eTailer competition, The results are in. See the top Information on PYMNTS.com supermarkets are turning to customer- scorers and a provider directory and Mobeewave facing scan-and-go-apps or equipping featuring 314 players in the space, employees with handheld devices to including four additions. make purchasing more convenient and win new business ACKNOWLEDGMENT The mPOS Tracker™ was done in collaboration with Mobeewave, and PYMNTS is grateful for the company’s support and insight. PYMNTS.com retains full editorial control over the findings presented, as well as the methodology and data analysis. mPOS Tracker™ © 2019 PYMNTS.com All Rights Reserved February 2019 | 2 WHAT’S INSIDE Whether in store or online, catering to modern consumers means providing them with a unified retail experience. Consumers want to smoothly transition from online shopping to browsing a physical retail store, and 56 percent say they would be more likely to patronize a store that offered them a shared cart across channels. -

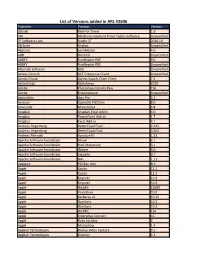

List of Versions Added in ARL #2606

List of Versions added in ARL #2606 Publisher Product Version 3bitlab Red Hot Timer 1.9 3M Medicare Inpatient Pricer Tables Software Unspecified 3T Software Labs Studio 3T 2020.10 AB Sciex Analyst Unspecified Abacom LochMaster 4.0 ABB WinCCU Unspecified ABBYY FineReader PDF 9.0 ABBYY FineReader PDF Unspecified Absolute Software DDS Unspecified Access Control ACT Enterprise Client Unspecified Access Group Access Supply Chain Client 7.2 ActiveCrypt DbDefence 2020 Adobe Photoshop Camera Raw CS6 Adobe Dreamweaver Unspecified algoriddim djay Pro 2.2 Amazon OpenJDK Platform 8.0 Anaconda Miniconda3 3.8 Anaplan Anaplan Excel Addin 4.0 Anaplan PowerPoint Add-in 1.7 Anaplan Excel Add-in 4.1 Andreas Hegenberg BetterTouchTool 2.425 Andreas Hegenberg BetterTouchTool 3.505 Andreas Pehnack Synalyze It! 1.23 Apache Software Foundation Hbase 2.1 Apache Software Foundation Hive Metastore 3.1 Apache Software Foundation JMeter 3.0 Apache Software Foundation zeppelin 0.7 Apache Software Foundation NiFi 1.11 Applanix POSPac UAV 8.5 Apple Xcode 12.1 Apple Xcode 12.2 Apple Keynote 10.2 Apple Keynote 10.3 Apple WebKit 15609 Apple VoiceOver 10.0 Apple Kerberos v5 10.15 Apple Numbers 10.2 Apple Numbers 10.3 Apple WebKit 156 Apple Enterprise Connect 16 Apple Ruby for Mac 2 Apple Monodraw 1.4 Applian Technologies Replay Video Capture 9.1 Applian Technologies Director 4.3 Applied Systems WealthTrack 10.0 Aranda Software Asset Management Unspecified ArcSoft WD Backup Unspecified ASG Technologies ASG-Zena Platform Agent 4.1 Aspose Aspose.Words for Reporting Services -

Introduction to Managing Mobile Devices Using Linux on System Z

Introduction to Managing Mobile Devices using Linux on System z SHARE Pittsburgh – Session 15692 Romney White ([email protected]) System z Architecture and Technology © 2014 IBM Corporation Mobile devices are 80% of devices sold to access the Internet Worldwide Shipment of Internet Access Devices 2013 2017 PC (Desktop & Notebook) PC (Ultrabook) Tablet Phone Worldwide Devices Shipments by Segment (Thousands of Units) Device Type 2012 2013 2014 2017 PC (Desk-Based and Notebook) 341,263 315,229 302,315 271,612 PC (Ultrabooks) 9,822 23,592 38,687 96,350 Tablet 116,113 197,202 265,731 467,951 Mobile Phone 1,746,176 1,875,774 1,949,722 2,128,871 Total 2,213,373 2,411,796 2,556,455 2,964,783 2 Source: Gartner (April 2013) © 2014 IBM Corporation Mobile Internet users will surpass PC internet users by 2015 The number of people accessing the Internet from smartphones, tablets and other mobile devices will surpass the number of users connecting from a home or office computer by 2015, according to a September 2013 study by market analyst firm IDC. PC is the new Legacy! 3 © 2014 IBM Corporation Five mobile trends with significant implications for the enterprise Mobile enables the Mobile is primary Internet of Things Mobile is primary 91% of mobile users keep Global Machine-to-machine 91% of mobile users keep their device within arm’s connections will increase their device within arm’s reach 100% of the time from 2 billion in 2011 to 18 reach 100% of the time billion at the end of 2022 Mobile must create a continuous brand Insights from mobile experience -

Software Withdrawal and Service Discontinuance: IBM Middleware, IBM Security, IBM Analytics, IBM Storage Software, and IBM Z

IBM United States Withdrawal Announcement 916-117, dated September 13, 2016 Software withdrawal and service discontinuance: IBM Middleware, IBM Security, IBM Analytics, IBM Storage Software, and IBM z Systems select products - Some replacements available Table of contents 1 Overview 107Replacement program information 10 Withdrawn programs 210Corrections Overview Effective on the dates shown, IBM(R) will withdraw support for the following program's VRM licensed under the IBM International Program License Agreement: VRM (V3.2.1) Note: V= All means all versions Note: V#.x means all releases of the version # listed Note: V#.#.x means all mods of the version release # listed For Advanced Administration System (AAS) Systems products Program number Program release VRM Withdrawal from name support date 5608-W07 IBM Tivoli(R) 3.2.x September 30, Storage 2017 (See Note FlashCopy(R) SUPT below) Manager For Passport Advantage(R) (PPA) On Premises products IBM Analytics products Program number Program release VRM Withdrawal from name support date 5639-I80 IBM Content 2.3.x September 30, Manager 2018 ImagePlus(R) Workstation program 5722-VI1 IBM DB2(R) 5.3.x September 30, Content Manager 2018 for iSeries 5724-B35 IBM InfoSphere(R) 5.5.x September 30, OptimTM 2016 Application Repository Analyzer 5724-B35 IBM InfoSphere 6.x September 30, Optim Application 2016 Repository Analyzer IBM United States Withdrawal Announcement 916-117 IBM is a registered trademark of International Business Machines Corporation 1 Program number Program release VRM Withdrawal -

Is Payment Tokenization Ready for Primetime?

Is Payment Tokenization Ready for Primetime? Perspectives from Industry Stakeholders on the Tokenization Landscape Marianne Crowe and Susan Pandy, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston David Lott, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Steve Mott, BetterBuyDesign June 11, 2015 Marianne Crowe is Vice President and Susan Pandy is Director in the Payments Strategies Group at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. David Lott is a Payments Risk Expert in the Retail Payments Risk Forum at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Steve Mott is the Principal of BetterBuyDesign. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta or Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Mention or display of a trademark, proprietary product or firm in this report does not constitute an endorsement or criticism by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System and does not imply approval to the exclusion of other suitable products or firms. The authors would like to thank members of the MPIW and other industry stakeholders for their engagement and contributions to this report. Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 3 II. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 III. Overview of Tokenization ...................................................................................................... -

Boa Motion to Dismiss

Case 21-10036-CSS Doc 211-4 Filed 02/15/21 Page 425 of 891 Disposition of the Stapled Securities Gain on sale of Stapled Securities by a Non-U.S. Stapled Securityholder will not be subject to U.S. federal income taxation unless (i) the Non-U.S. Stapled Securityholder’s investment in the Stapled Securities is effectively connected with its conduct of a trade or business in the United States (and, if provided by an applicable income tax treaty, is attributable to a permanent establishment or fixed base the Non-U.S. Stapled Securityholder maintains in the United States) and a properly completed Form W-8ECI has not been provided, (ii) the Non-U.S. Stapled Securityholder is present in the United State for 183 days or more in the taxable year of the sale and other specified conditions are met, or (iii) the Non-U.S. Stapled Securityholder is subject to U.S. federal income tax pursuant to the provisions of the U.S. tax law applicable to U.S. expatriates. If gain on the sale of Stapled Securities would be subject to U.S. federal income taxation, the Stapled Securityholder would generally recognise any gain or loss equal to the difference between the amount realised and the Stapled Securityholder’s adjusted basis in its Stapled Securities that are sold or exchanged. This gain or loss would be capital gain or loss, and would be long-term capital gain or loss if the Stapled Securityholder’s holding period in its Stapled Securities exceeds one year. In addition, a corporate Non-U.S. -

IBM® Security Trusteer Rapport™- Extension Installation

Treasury & Payment Solutions Quick Reference Guide IBM® Security Trusteer Rapport™- Extension Installation For users accessing Web-Link with Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox, Rapport is also available to provide the same browser protection as is provided for devices using Internet Explorer. This requires that a browser extension be enabled. A browser extension is a plug-in software tool that extends the functionality of your web browser without directly affecting viewable content of a web page (for example, by adding a browser toolbar). Google Chrome Extension - How to Install: To install the extension from the Rapport console: 1. Open the IBM Security Trusteer Rapport Console by clicking Start>All Programs>Trusteer Endpoint Protection>Trusteer Endpoint Protection Console. 2. In the Product Settings area, next to ‘Chrome extension’, click install. Note: If Google Chrome is not set as your default browser, the link will open in whichever browser is set as default (e.g., Internet Explorer, as in the image below). 3. Copy the URL from the address bar below and paste it into a Chrome browser to continue: https://chrome.google.com/ webstore/detail/rapport/bbjllphbppobebmjpjcijfbakobcheof 4. Click +ADD TO CHROME to add the extension to your browser: Tip: If the Trusteer Rapport Console does not lead you directly to the Chrome home page, you can: 1. Click the menu icon “ ” at the top right of the Chrome browser window, choose “Tools” and choose “Extensions” to open a new “Options” tab. 1 Quick Reference Guide IBM Security Trusteer Rapport™ -Extension Installation 2. Select the Get more extensions link at the bottom of the page.