Program Notes by MARTIN BOOKSPAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAN 3000 FRONT.Qxd

CHAN 3000 FRONT.qxd 22/8/07 1:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 3000(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION Puccini TOSCA CHAN 3000(2) BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Tosca AKG An opera in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou English version by Edmund Tracey Floria Tosca, celebrated opera singer ..............................................................Jane Eaglen soprano Mario Cavaradossi, painter ..........................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Baron Scarpia, Chief of Police................................................................Gregory Yurisich baritone Cesare Angelotti, resistance fighter ........................................................................Peter Rose bass Sacristan ....................................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Spoletta, police agent ........................................................................................John Daszak tenor Sciarrone, Baron Scarpia’s orderly ..............................................Christopher Booth-Jones baritone Jailor ........................................................................................................Ashley Holland baritone A Shepherd Boy ............................................................................................Charbel Michael alto Geoffrey Mitchell Choir The Peter Kay Children’s Choir Giacomo Puccini, c. 1900 -

View the Program!

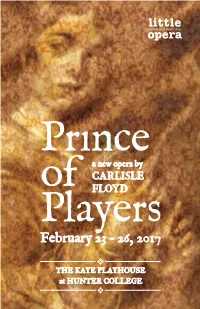

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected]

Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 14 (2017), pp 211–242. © Cambridge University Press, 2016 doi:10.1017/S1479409816000082 First published online 8 September 2016 Romantic Nostalgia and Wagnerismo During the Age of Verismo: The Case of Alberto Franchetti* Davide Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected] The world premiere of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana on 17 May 1890 immediately became a central event in Italy’s recent operatic history. As contemporary music critic and composer, Francesco D’Arcais, wrote: Maybe for the first time, at least in quite a while, learned people, the audience and the press shared the same opinion on an opera. [Composers] called upon to choose the works to be staged, among those presented for the Sonzogno [opera] competition, immediately picked Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana as one of the best; the audience awarded this composer triumphal honours, and the press 1 unanimously praised it to the heavens. D’Arcais acknowledged Mascagni’smeritsbut,inthesamearticle,alsourgedcaution in too enthusiastically festooning the work with critical laurels: the dangers of excessive adulation had already become alarmingly apparent in numerous ill-starred precedents. In the two decades prior to its premiere, several other Italian composers similarly attained outstanding critical and popular success with a single work, but were later unable to emulate their earlier achievements. Among these composers were Filippo Marchetti (Ruy Blas, 1869), Stefano Gobatti (IGoti, 1873), Arrigo Boito (with the revised version of Mefistofele, 1875), Amilcare Ponchielli (La Gioconda, 1876) and Giovanni Bottesini (Ero e Leandro, 1879). Once again, and more than a decade after Bottesini’s one-hit wonder, D’Arcais found himself wondering whether in Mascagni ‘We [Italians] have finally [found] … the legitimate successor to [our] great composers, the person 2 who will perpetuate our musical glory?’ This hoary nationalist interrogative returned in 1890 like an old-fashioned curse. -

Franchetti Prog Di Sala FIRENZE

Presentazione del volume ALBERTO FRANCHETTI: L’UOMO, IL COMPOSITORE, L’ARTISTA a cura di Paolo Giorgi e Richard Erkens - Lucca, Libreria Musicale Italiana, 2015 Firenze, Sala del Buonumore - Conservatorio “Luigi Cherubini” Sabato 18 giugno 2016, ore 17 Davide Ceriani, Cesare Orselli, Richard Erkens relatori Il compositore Alberto Franchetti (1860-1942), eminente personalità del cosiddetto 'lungo Ottocento' musicale, fu uno dei più conosciuti compositori della Giovane Scuola italiana, insieme a Giacomo Puccini, Pietro Mascagni e Ruggero Leoncavallo; grazie ai successi operistici internazionali delle sue opere liriche Asrael (1888), Cristoforo Colombo (1892) e Germania (1902), Franchetti ebbe una notevole fama fino agli anni Venti del XX secolo, per poi cadere nell'oblio fino agli anni più recenti. Nel settembre 2010 è stato organizzato, a cura dell' Associazione per il musicista Alberto Franchetti di Reggio Emilia, un convegno internazionale sulla sua figura, volto a dare l'avvio ad una nuova valorizzazione a lui e alla sua opera. Gli atti del convegno, ampliati nei contenuti e curati da Paolo Giorgi e Richard Erkens, costituiscono il volume Alberto Franchetti: l'uomo, il compositore, l'artista (LIM, 2015) a cura di, nel quale si affronta la figura del compositore sotto vari aspetti: l'analisi delle composizioni sinfoniche, gli aspetti drammatico- musicali delle sue numerose e articolate opere liriche, e la ricezione in Europa e in America della sua produzione; completa il volume una ricca sezione di documenti, riguardanti nuove fonti biografiche, lettere manoscritte inedite che riguardano la collaborazione tra Franchetti e Gabriele D’Annunzio per realizzazione de La figlia di Iorio del1906, nonché il catalogo del Fondo Alberto Franchetti depositato dal 2013 presso la Biblioteca Panizzi di Reggio Emilia. -

Beverly Sills, 1929-2007: a Beautiful Voice for Opera and the Arts

20 April 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com Beverly Sills, 1929-2007: A Beautiful Voice for Opera and the Arts AP Opera singer Beverly Sills, right, with her daughter Muffy, and her mother Shirley Silverman, left, in this Dec. 19, 1988 photo at New York's Plaza Hotel STEVE EMBER: I’m Steve Ember. BARBARA KLEIN: And I’m Barbara Klein with PEOPLE IN AMERICA in VOA Special English. Today we tell about Beverly Sills. Her clear soprano voice and lively spirit made her one of the most famous performers in the world of opera. Sills worked hard to make opera an art form that the general public could enjoy. She spent the later part of her career as a strong cultural leader for three major performing arts centers in New York City. (MUSIC) STEVE EMBER: That was Beverly Sills performing a song from the opera “The Tales of Hoffman” by the French composer Jacques Offenbach. Sills is singing the role of Olympia, a female robot who keeps breaking down while singing a series of high notes. This difficult aria gives a good example of the sweet and expressive voice that made Beverly Sills famous. 2 AP The Brooklyn-born opera diva was a global icon of can-do American culture with her dazzling voice and bubbly personality BARBARA KLEIN: Beverly Sills was born Belle Silverman in nineteen twenty-nine. Her family lived in the Crown Heights area of Brooklyn, New York. Her father, Morris, came from Romania and her mother, Shirley, was Russian. Sills said that her father believed that a person could live the real American dream only with an educated mind. -

Renée Fleming Sings Her First La Traviata

DAVID GOCKLEY, GENERAL DIRECTOR PATRICK SUMMERS, MUSIC DIRECTOR Subscribe Now! 2002–2003 Season Renée Fleming sings her first La Traviata. See it FREE when you SUBSCRIBE NOW! DHoustonivas,divas,divas! Grand Opera celebrates “The Year of the Diva.” Renée Fleming will at long last sing her first Violetta—and, where might this Experience all the anticipated debut happen? The Met? La Scala? Vienna? No, Renée has chosen to excitement and premiere this significant role here at Houston Grand Opera. In a year of firsts— Susan Graham’s first Ariodante and The Merry Widow and Elizabeth Futral’s benefits of a full first Manon—Ms.Fleming’s Violetta will be a defining moment in the world of opera. season subscription: The season begins with the return of Ana Maria Martinez as Mimi in Puccini’s • Free parking beloved La Bohème. Laura Claycomb,the young Te x a s soprano who had • Free subscription to audiences on their feet in this season’s Rigoletto,will return in Donizetti’s Scottish Opera Cues magazine masterpiece, Lucia di Lammermoor.The season closes with the world premiere of • Free season preview The Little Prince,when Oscar-winning composer Rachel Portman turns Antoine CD or cassette de Saint-Exupéry’s much loved novel into a magical and moving opera. • Free lost ticket replacement Extraordinary singers in extraordinary productions.As a full season subscriber, • Exchange privileges you get 7 operas for the price of 6. That means you can see Renée Fleming’s debut • 10% discount on as Violetta for free! I urge you to take advantage of this offer, it’s the only way we additional tickets can guarantee you a seat. -

Nyco Renaissance

NYCO RENAISSANCE JANUARY 10, 2014 Table of Contents: 1. Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 2. History .......................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Core Values .................................................................................................................................. 5 4. The Operatic Landscape (NY and National) .............................................................................. 8 5. Opportunities .............................................................................................................................. 11 6. Threats ......................................................................................................................................... 13 7. Action Plan – Year 0 (February to August 2014) ......................................................................... 14 8. Action Plan – Year 1 (September 2014 to August 2015) ............................................................... 15 9. Artistic Philosophy ...................................................................................................................... 18 10. Professional Staff, Partners, Facilities and Operations ............................................................. 20 11. Governance and Board of Directors ......................................................................................... -

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER March 20, 2002, 8:00 P.M. on PBS the New York City Opera: the Gershwins®' Porgy and Bess

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER March 20, 2002, 8:00 p.m. on PBS The New York City Opera: The Gershwins®' Porgy and Bess The next Live From Lincoln Center telecast, on Wednesday evening March 20, will find us in the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center for the performance by the New York City Opera of The Gershwins® beloved opera PORGY AND BESS . As the years go by, this masterpiece of the American musical theater gains in stature and popularity, and it has become a staple in opera houses throughout the world. Our production is the one created to great acclaim by Sherwin M. Goldman in 1983 for Radio City Music Hall, based on his co- production with Houston Grand Opera which won Broadway’s Tony Award in 1976 for Best Musical Revival. John DeMain, conductor of the original Houston performances, will be in the pit, and the Production Director is Tazewell Thompson. The creation of PORGY AND BESS was not without its difficulties. In late 1926 George and Ira Gershwin were working on a new musical tailored for the specific talents of the remarkable British singer and actress, Gertrude Lawrence. After several working titles were abandoned, the show finally emerged as Oh, Kay. It became a solid hit. During the rehearsals for Oh, Kay Gershwin read a novel by the Southern poet, DuBose Heyward, titled Porgy. He sensed immediately that here was material for an opera, but Heyward informed him that the rights were unavailable, having been assigned to the Theater Guild for a proposed stage adaptation. It was Heyward’s wife, Dorothy, who had secretly made the adaptation for the stage. -

JUNE 2016 World Premiere of David Hertzberg's “Sunday Morning”

NEW YORK CITY OPERA RETURNS WITH THREE PREMIERES MARCH - JUNE 2016 World Premiere of David Hertzberg’s “Sunday Morning” at Inaugural New York City Opera Concerts at Appel Room in March 2016 East Coast Premiere of Hopper’s Wife at Harlem Stage in April 2016 New York City Professional Premiere of Florencia en el Amazonas Launches Spanish-language Opera Series: Ópera en Español Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater in June 2016 February 22, 2016 – New York City Opera General Director Michael Capasso today announced the remainder of the 2016 season. New York City Opera will present three major premieres including the world premiere of “Sunday Morning” by David Hertzberg as part of the inaugural New York City Opera Concerts at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Appel Room on March 16; the East Coast premiere of Stewart Wallace and Michael Korie’s Hopper’s Wife presented at Harlem Stage in April 2016 and the New York City professional premiere of Daniel Catán’s Florencia en el Amazonas at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater in June 2016. Florencia en el Amazonas launches Spanish-language Opera Series, Ópera en Español. Michael Capasso discussed the season, “In continuing with my vision for New York City Opera, these three offerings of contemporary music balance the traditional Tosca production with which we re-launched the company in January. Historically, New York City Opera presented a combination of core and contemporary repertoire; this programming represents our commitment to maintaining that approach. The initiation of our New York City Opera Concerts at the Appel Room will demonstrate further our company’s versatility and goal to present events that complement our staged productions. -

FINAL Tosca 2018

Stories Told Through Singing TOSCA Giacomo Puccini OPERA: Stories Told Through Singing At Palm Beach Opera, we believe that opera tells stories to which we can all relate, and that is why the operatic art form has thrived for centuries. The education programs at Palm Beach Opera plug the community directly into those stories, revealing timeless tales of love, passion, and joy. We challenge each person to find their own connection to opera’s stories, inspiring learners of all ages to explore the world of opera. At Palm Beach Opera there is something for everyone! #PBOperaForAll 1 PBOPERA.ORG // 561.833.7888 TOSCA Giacomo Puccini The Masterminds pg 3 Who's Who pg 7 Understanding the Action pg 9 Engage Your Mind pg 13 PBOPERA.ORG // 561.833.7888 2 The Masterminds 3 PBOPERA.ORG // 561.833.7888 Giacomo Puccini Composer Giacomo Puccini (December 22, 1858 – November 29, 1924) was born into a musical family. He studied composition at the Milan Conservatory, writing his first opera in 1884 at the age of 26. A prolific composer, Puccini wrote many operas including several that are still in performance today: Manon Lescaut, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, La fanciulla del West, La rondine, Suor Angelica, Gianni Schicchi, Turandot, and La bohème. Although the designation of Puccini as a verismo composer is debated, many of his works can fit in this category. Verismo is derived from the Italian word ‘vero’ meaning'true;' the style is distinguished by realistic lines and genuine characters. Fun Factoid: Puccini's full name was Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini. -

Puccini Tosca Act3 E Lucevan Le Stelle Tenor and Piano Sheet Music

Puccini Tosca Act3 E Lucevan Le Stelle Tenor And Piano Sheet Music Download puccini tosca act3 e lucevan le stelle tenor and piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of puccini tosca act3 e lucevan le stelle tenor and piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 6601 times and last read at 2021-09-25 04:04:27. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of puccini tosca act3 e lucevan le stelle tenor and piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Tenor Voice, Voice Solo, Piano Accompaniment Ensemble: Mixed Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music E Lucevan Le Stelle From Tosca By Giacomo Puccini Arranged For String Orchestra By Adrian Mansukhani E Lucevan Le Stelle From Tosca By Giacomo Puccini Arranged For String Orchestra By Adrian Mansukhani sheet music has been read 12618 times. E lucevan le stelle from tosca by giacomo puccini arranged for string orchestra by adrian mansukhani arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 20:33:55. [ Read More ] E Lucevan Le Stelle From Tosca G Puccini Arranged For Tenor Voice And Concert Band E Lucevan Le Stelle From Tosca G Puccini Arranged For Tenor Voice And Concert Band sheet music has been read 2872 times. E lucevan le stelle from tosca g puccini arranged for tenor voice and concert band arrangement is for Intermediate level. -

Leggi Qualche Pagina

saggi 1 © 2017 Ronzani Editore Vicenza | Elabora S.r.l. Viale del Progresso, 10 | 36010 Monticello Conte Otto (Vi) www.ronzanieditore.it | [email protected] ISBN 978-88-94911-06-0 Alessandro Duranti IL MELOMANE DOMESTICO Maria Callas e altri scritti sull’opera RE Ronzani Editore INDICE 7 Prefazione 13 Maria Callas, ovvero Tutte le torture 53 Verdi e l’arte del mutare la maniera 63 Note veriste. Mascagni e gli altri « nemici della musica» 109 Maremoto a Massaciuccoli. Il Novecento di Puccini 125 Toscanini, la vecchiaia, l’opera e il disco 141 Montale ‘en travesti ’ 161 Indice dei nomi Prefazione « Chi scrive non sa di musica»: inizia così la Filosofia della Musica (1836) di Giuseppe Mazzini e allo stesso modo ini- zio io, colpito da un attacco di megalomania fulminante, ma del resto, se ci sono i pazzi che si credono Napoleone o Garibaldi, mi sento perfino in buona compagnia. Quanto alle mie competenze musicali, non so neanche cantare a orecchio, come si dice abbiano fatto e facciano cantanti celeberrimi. Credo di essere la creatura più stonata dell’u- niverso e quando ascolto certe masterclass di grandi can- tanti e grandi didatti (ne sono state pubblicate varie, per esempio di Alfredo Kraus, di Beniamino Gigli o della stes- sa Callas) rimango sempre stupito e ammirato che qualcu- no possa aprire bocca e cantare davvero, bene o male non importa, dopo aver saputo quanti e quali ingranaggi del suo corpo – diaframmi, tonsille, laringi, polmoni, coratelle varie, cavità facciali, alluci, lobi degli orecchi (il baritono Giuseppe Valdengo, quello di Toscanini, ci aggiungeva an- che una parte del corpo meno nobile) – devono accordarsi per poterlo fare.