Introducing the S20 Wildlife Corridor an Alternative Proposal for Owlthorpe Fields: Towards a Heathier South East Sheffield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lavender Row, 23 Hallside Court, Mosborough, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, S20 5EP

Lavender Row, 23 Hallside Court, Mosborough, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, S20 5EP 23 Hallside Court, Mosborough, S20 5EP Nestled at the end of this exclusive cul-de-sac, Lavender Row is a charming stone-built family residence of character with beautiful landscaped gardens and stunning views over the Moss Valley. Offering an impressive 6 reception areas and 5 bedrooms over 2 floors, this detached home has features that include solid wood flooring and a multi-fuel burner. Tastefully extended in 2001, the modern extension gives this Victorian property both a large sitting room and master suite that enjoy wonderful views across rolling greenbelt farm land. The house was re-roofed in 2015 and now includes a large, boarded out attic for storage. The property also includes a double garage and parking for multiple vehicles. Lavender Row is one of only 4 houses on this small and exclusive development to the rear of Hallside Court. The highly versatile and generously proportioned house is well-served by local amenities in Eckington and Mosborough and is within easy reach of Sheffield City centre and the M1. Spacious, oak-floored reception hall with room for seating Highly versatile kitchen-diner. Large bay window with views over the garden 2 additional reception rooms with adjoining double- sided stove. Currently used as snug and pool room Large living room with panoramic windows to enjoy the stunning views Versatile home office/play room/home gym Separate utility room, porch and ground floor W.C Large master suite with Juliette balcony, great -

Agenda Item 3

Agenda Item 3 Minutes of the Meeting of the Council of the City of Sheffield held in the Council Chamber, Town Hall, Pinstone Street, Sheffield S1 2HH, on Wednesday 5 December 2012, at 2.00 pm, pursuant to notice duly given and Summonses duly served. PRESENT THE LORD MAYOR (Councillor John Campbell) THE DEPUTY LORD MAYOR (Councillor Vickie Priestley) 1 Arbourthorne Ward 10 Dore & Totley Ward 19 Mosborough Ward Julie Dore Keith Hill David Barker John Robson Joe Otten Isobel Bowler Jack Scott Colin Ross Tony Downing 2 Beauchiefl Greenhill Ward 11 East Ecclesfield Ward 20 Nether Edge Ward Simon Clement-Jones Garry Weatherall Anders Hanson Clive Skelton Steve Wilson Nikki Bond Roy Munn Joyce Wright 3 Beighton Ward 12 Ecclesall Ward 21 Richmond Ward Chris Rosling-Josephs Roger Davison John Campbell Ian Saunders Diana Stimely Martin Lawton Penny Baker Lynn Rooney 4 Birley Ward 13 Firth Park Ward 22 Shiregreen & Brightside Ward Denise Fox Alan Law Sioned-Mair Richards Bryan Lodge Chris Weldon Peter Price Karen McGowan Shelia Constance Peter Rippon 5 Broomhill Ward 14 Fulwood Ward 23 Southey Ward Shaffaq Mohammed Andrew Sangar Leigh Bramall Stuart Wattam Janice Sidebottom Tony Damms Jayne Dunn Sue Alston Gill Furniss 6 Burngreave Ward 15 Gleadless Valley Ward 24 Stannington Ward Jackie Drayton Cate McDonald David Baker Ibrar Hussain Tim Rippon Vickie Priestley Talib Hussain Steve Jones Katie Condliffe 7 Central Ward 16 Graves Park Ward 25 Stockbridge & Upper Don Ward Jillian Creasy Ian Auckland Alison Brelsford Mohammad Maroof Bob McCann Philip Wood Robert Murphy Richard Crowther 8 Crookes Ward 17 Hillsborough Ward 26 Walkey Ward Sylvia Anginotti Janet Bragg Ben Curran Geoff Smith Bob Johnson Nikki Sharpe Rob Frost George Lindars-Hammond Neale Gibson 9 Darnall Ward 18 Manor Castle Ward 27 West Ecclesfield Ward Harry Harpham Jenny Armstrong Trevor Bagshaw Mazher Iqbal Terry Fox Alf Meade Mary Lea Pat Midgley Adam Hurst 28 Woodhouse Ward Mick Rooney Jackie Satur Page 5 Page 6 Council 5.12.2012 1. -

On the Disturbances in the District of the Valley of The

Downloaded from http://pygs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 mittee, for their kind assistance in making the arrangements for the meeting. The following communications were then made to the Society :— ON THE DISTURBANCES IN THE DISTRICT OP THE VALLEY OF THE DON. BY REV. WM. THORP, OF WOMERSLEY. Upon the last visit of the Society to Sheffield, I had the pleasure of describing some of the geological features of the neighbouring district, and particularly those of the country between Rotherham and Sheffield. I have again taken the liberty of giving a brief mining notice of the disturbances of the same district, because they are not only of such enor mous magnitude as to be of great interest to the geologist, but a knowledge of them is necessary to the successful min ing operations of that neighbourhood. Upon the former occasion, it was contended by one party that not only were the strata on the North side of the Don elevated above those of the South side, to the amount of 600 yards in vertical height; but that also there had been a horizontal lateral movement of the beds of the North side, in an eastward direction, to the length of five or six miles.^ * The proofs then adduced in support of a lateral movement were—1. That the various beds come from the North, up to the edge of the valley of the Don, but do not preserve their Northerly and Southerly direction across the valley, but are found several miles to the West; e. g.^the Silkstone coal ranges to Dropping Well, near Kimberworth, and is not found at the same depth until we arrive six miles West, at SheflSeld town. -

(25) Manor Park Sheffield He

Bus service(s) 24 25 Valid from: 18 July 2021 Areas served Places on the route Woodhouse Heeley Retail Park Stradbroke Richmond (25) Moor Market Manor Park SHU City Campus Sheffield Heeley Woodseats Meadowhead Lowedges Bradway What’s changed Service 24/25 (First) - Timetable changes. Service 25 (Stagecoach) - Timetable changes. Operator(s) Some journeys operated with financial support from South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 24 and 25 26/05/2016# Catclie Ð Atterclie Rivelin Darnall Waverley Crookes Sheeld, Arundel Gate Treeton Ð Crosspool Park Hill Manor, Castlebeck Av/Prince of Wales Rd Ð Sheeld, Arundel Gate/ Broomhill Ð SHU City Campus Sandygate Manor, Castlebeck Av/Castlebeck Croft Sheeld, Fitzwilliam Gate/Moor Mkt Ð Manor Park, Manor Park Centre/ Ð Harborough Av 24 Nether Green Hunters Bar Sharrow Lowfield, Woodhouse, Queens Rd/ 25 Cross St/ Retail Park Tannery St Fulwood Greystones 24, 25 Nether Edge 24 25 High Storrs 25 Richmond, Heeley, Chesterfield Rd/Beeton Rd Hastilar Rd South/ 25 Richmond Rd Heeley, Chesterfield Rd/Heeley Retail Park Woodhouse, Woodhouse, Gleadless Stradbroke Rd/ Skelton Ln/ Ringinglow Sheeld Rd Skelton Grove Beighton Gleadless Valley Hackenthorpe Millhouses Norton Lees Birley Woodseats, Chesterfield Rd/Woodseats Library Herdings Charnock Owlthorpe Waterthorpe Woodseats, Chesterfield Rd/Bromwich Rd Abbeydale Beauchief High Lane Norton 24, 25 Westfield database right 2016 Dore 25 Abbeydale Park Mosborough and Greenhill Ridgeway yright p o c Halfway own 24, 25 r C Bradway, Prospect Rd/Everard Av data © 24 25 24 y e 24 v Sur e Lowedges, Lowedges Rd/The Grennel Mower c dnan Bradway, Longford Rd r O Totley Apperknowle Marsh Lane Eckington ontains C 6 = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop Hail & ride Along part of the route you can stop the bus at any safe and convenient point - but please avoid parked vehicles and road junctions. -

Rotherham Sheffield

S T E A D L To Penistone AN S NE H E LA E L E F I RR F 67 N Rainborough Park N O A A C F T E L R To Barnsley and I H 61 E N G W A L A E W D Doncaster A L W N ELL E I HILL ROAD T E L S D A T E E M R N W A R Y E O 67 O G O 1 L E O A R A L D M B N U E A D N E E R O E O Y N TH L I A A C N E A Tankersley N L L W T G N A P E O F A L L A A LA E N LA AL 6 T R N H C 16 FI S 6 E R N K Swinton W KL D 1 E BER A E T King’s Wood O M O 3 D O C O A 5 A H I S 67 OA A W R Ath-Upon-Dearne Y R T T W N R S E E E RR E W M Golf Course T LANE A CA 61 D A 6 A O CR L R R B E O E D O S A N A A S A O M L B R D AN E E L GREA Tankersley Park A CH AN AN A V R B ES L S E E D D TER L LDS N S R L E R R A R Y I E R L Golf Course O N O IE O 6 F O E W O O E 61 T A A F A L A A N K R D H E S E N L G P A R HA U L L E WT F AN B HOR O I E O E Y N S Y O E A L L H A L D E D VE 6 S N H 1 I L B O H H A UE W 6 S A BR O T O E H Finkle Street OK R L C EE F T O LA AN H N F E E L I E A L E A L N H I L D E O F Westwood Y THE River Don D K A E U A6 D H B 16 X ROA ILL AR S Y MANCHES Country Park ARLE RO E TE H W MO R O L WO R A N R E RT RT R H LA N E O CO Swinton Common N W A 1 N Junction 35a D E R D R O E M O A L DR AD O 6 L N A CL AN IV A A IN AYFIELD E OOBE E A A L L H R D A D S 67 NE LANE VI L E S CT L V D T O I H A L R R A E H YW E E I O N R E Kilnhurst A W O LI B I T D L E G G LANE A H O R D F R N O 6 R A O E N I O 2 Y Harley A 9 O Hood Hill ROAD K N E D D H W O R RTH Stocksbridge L C A O O TW R N A Plantation L WE R B O N H E U Y Wentworth A H L D H L C E L W A R E G O R L N E N A -

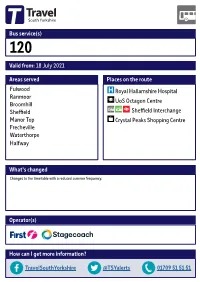

Valid From: 18 July 2021 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas Served Fulwood Ranmoor Broomhill Sheffield Manor Top Frecheville

Bus service(s) 120 Valid from: 18 July 2021 Areas served Places on the route Fulwood Royal Hallamshire Hospital Ranmoor UoS Octagon Centre Broomhill Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Manor Top Crystal Peaks Shopping Centre Frecheville Waterthorpe Halfway What’s changed Changes to the timetable with a reduced summer frequency. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 120 Walkley 17/09/2015 Sheeld, Tinsley Park Stannington Flat St Catclie Sheeld, Arundel Gate Sheeld, Interchange Darnall Waverley Treeton Broomhill,Crookes Glossop Rd/ 120 Rivelin Royal Hallamshire Hosp 120 Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/ 120 Wybourn Ranmoor Park Rd Littledale Fulwood, Barnclie Rd/ 120 Winchester Rd Western Bank, Manor Park Handsworth Glossop Road/ 120 120 Endclie UoS Octagon Centre Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/Riverdale Rd Norfolk Park Manor Fence Ô Ò Hunters Bar Ranmoor, Fulwood Rd/ Fulwood Manor Top, City Rd/Eastern Av Hangingwater Rd Manor Top, City Rd/Elm Tree Nether Edge Heeley Woodhouse Arbourthorne Intake Bents Green Carter Knowle Ecclesall Gleadless Frecheville, Birley Moor Rd/ Heathfield Rd Ringinglow Waterthorpe, Gleadless Valley Birley, Birley Moor Rd/ Crystal Peaks Bus Stn Birley Moor Cl Millhouses Norton Lees Hackenthorpe 120 Birley Woodseats Herdings Whirlow Hemsworth Charnock Owlthorpe Sothall High Lane Abbeydale Beauchief Dore Moor Norton Westfield database right 2015 Dore Abbeydale Park Greenhill Mosborough and Ridgeway 120 yright p o c Halfway, Streetfields/Auckland Way own r C Totley Brook -

Elm Crescent, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Guide Price £190,000 - £200,000

Elm Crescent, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Guide Price £190,000 - £200,000 Don't miss your opportunity to purchase this modern and spacious • THREE DOUBLE throughout three double bedroom semi-detached property situated on a BEDROOMS big corner plot in the highly sought after village of Mosborough. Offering • SEMI-DETACHED downstairs WC, conservatory, off road parking and well maintained • MODERN AND SPACIOUS garden. The property is well positioned for local amenities and road links THROUGHOUT to Sheffield City Centre and the M1 Motorway. This property is ideal for a • DOWNSTAIRS WC first time buyers or families alike! • CONSERVATORY Elm Crescent, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Property Description Don't miss your opportunity to purchase this modern and spacious throughout three double bedroom semi- detached property situated on a big corner plot in the highly sought after village of Mosborough. Offering downstairs WC, conservatory, off road parking and well maintained garden. The property is well positioned for local amenities and road links to Sheffield City Centre and the M1 Motorway. This property is ideal for a first time buyers or families alike! HALLWAY Enter through composite door into welcoming hallway with neutral decor and wood effect laminate flooring. Ceiling light, radiator and stair rise to first floor landing. Doors to lounge, kitchen and downstairs WC. LOUNGE 15' 5" x 14' 10" (4.72m x 4.53m) A generous sized lounge with feature wall, laminate flooring and feature hole in wall currently housing a log burner and wood beam above. Ceiling light, radiator, TV point and two windows. Door to store room housing boiler. Elm Crescent, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 KITCHEN 10' 2" x 11' 1" (3.10m x 3.39m) A modern kitchen fitted with ample high gloss wall and base units, wood effect worktops and tiled splash backs. -

Ownership and Belonging in Urban Green Space

This is a repository copy of Ownership and belonging in urban green space. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118299/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Abram, S. and Blandy, S. (2018) Ownership and belonging in urban green space. In: Xu, T. and Clarke, A.C., (eds.) Legal Strategies for the Development and Protection of Communal Property; Proceedings of the British Academy. Proceedings of the British Academy . Oxford University Press , Oxford , pp. 177-201. ISBN 9780197266380 Ownership and Belonging in Urban Green Space, Dr Simone Abram and Professor Sarah Blandy, Legal Strategies for the Development and Protection of Communal Property edited by Ting Xu and Alison Clarke, 2018, reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press https://global.oup.com/academic/product/legal-strategies-for-the-development-and-protecti on-of-communal-property-9780197266380?cc=gb&lang=en Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Ownership and belonging in urban green space Simone Abram and Sarah Blandy Abstract This chapter examines urban green spaces which are accessible to the public, from both anthropological and socio-legal perspectives. -

Owlthorpe Rise, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Asking Price of £120,000

Owlthorpe Rise, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Asking Price Of £120,000 CHAIN FREE! Ideal for first time buyers, investors or buyers looking to NO CHAIN! downsize! Situated in a quiet cul-de-sac, this spacious ground floor apartment TWO BEDROOMS benefits from two good sized bedrooms and open plan living. Having allocated GROUND FLOOR FLAT parking and an enclosed rear garden. The property is located in the ever popular MODERN AND village of Mosborough with fantastic local amenities and main transport links close SPACIOUS by. With good road networks to the M1 Motorway and Sheffield City Centre. THROUGHOUT Call our sales team today to arrange your viewing! ALLOCATED PARKING Owlthorpe Rise, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 Property Description CHAIN FREE! Ideal for first time buyers, investors or buyers looking to downsize! Situated in a quiet cul-de-sac, this spacious ground floor apartment benefits from two good sized bedrooms and open plan living. Having allocated parking and an enclosed rear garden. The property is located in the ever popular village of Mosborough with fantastic local amenities and main transport links close by. With good road networks to the M1 Motorway and Sheffield City Centre. Call our sales team today to arrange your viewing! HALLWAY Entrance via a uPVC door into the hallway with neutral decor and carpeted flooring. Ceiling light, radiator and two storage cupboards. Doors lead to the lounge, two bedrooms and bathroom. LOUNGE 14' 6" x 10' 4" (4.42m x 3.16m) A spacious living area with neutral decor and carpeted flooring. Ceiling light, radiator and sliding patio doors lead Owlthorpe Rise, Mosborough, Sheffield, S20 to the outside. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Beauchief in Sheffield is a beautiful hillside at the foot of which, near the river Sheaf, and on the still wooded south-western fringes of the city, are the remains of the medieval abbey that housed, from the late twelfth century until the Henrician Reformation, Augustinian canons belonging to the Premonstratensian order. Augustinian canonries were generally modest places, although for reasons that have been persuasively advanced by the late Sir Richard Southern, this fact should never obscure the breadth of their significance in the wider history of medieval urban and rural localities: The Augustinian canons, indeed, as a whole, lacked every mark of greatness. They were neither very rich, nor very learned, nor very religious, nor very influential: but as a phenomenon they are very important. They filled a very big gap in the biological sequence of medieval religious houses. Like the ragwort which adheres so tenaciously to the stone walls of Oxford, or the sparrows of the English towns, they were not a handsome species. They needed the proximity of human habitation, and they throve on the contact which repelled more delicate organisms. They throve equally in the near-neighbourhood of a town or a castle. For the well-to-do townsfolk they could provide the amenity of burial-places, memorials and masses for the dead, and schools and confessors of superior standing for the living. For the lords of castles they could provide a staff for the chapel and clerks for the needs of administration. They were ubiquitously useful. They could live on comparatively little, yet expand into affluence without disgrace. -

State of Sheffield 03–16 Executive Summary / 17–42 Living & Working

State of Sheffield 03–16 Executive Summary / 17–42 Living & Working / 43–62 Growth & Income / 63–82 Attainment & Ambition / 83–104 Health & Wellbeing / 105–115 Looking Forwards 03–16 Executive Summary 17–42 Living & Working 21 Population Growth 24 People & Places 32 Sheffield at Work 36 Working in the Sheffield City Region 43–62 Growth & Income 51 Jobs in Sheffield 56 Income Poverty in Sheffield 63–82 Attainment & Ambition 65 Early Years & Attainment 67 School Population 70 School Attainment 75 Young People & Their Ambitions 83–104 Health & Wellbeing 84 Life Expectancy 87 Health Deprivation 88 Health Inequalities 1 9 Premature Preventable Mortality 5 9 Obesity 6 9 Mental & Emotional Health 100 Fuel Poverty 105–115 Looking Forwards 106 A Growing, Cosmopolitan City 0 11 Strong and Inclusive Economic Growth 111 Fair, Cohesive & Just 113 The Environment 114 Leadership, Governance & Reform 3 – Summary ecutive Ex State of Sheffield State Executive Summary Executive 4 The State of Sheffield 2016 report provides an Previous Page overview of the city, bringing together a detailed Photography by: analysis of economic and social developments Amy Smith alongside some personal reflections from members Sheffield City College of Sheffield Executive Board to tell the story of Sheffield in 2016. Given that this is the fifth State of Sheffield report it takes a look back over the past five years to identify key trends and developments, and in the final section it begins to explore some of the critical issues potentially impacting the city over the next five years. As explored in the previous reports, Sheffield differs from many major cities such as Manchester or Birmingham, in that it is not part of a larger conurbation or metropolitan area. -

Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2020 Respectable Women, Ambitious Men: Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield Autumn Mayle [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Gender Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Mayle, Autumn, "Respectable Women, Ambitious Men: Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield" (2020). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7530. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7530 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Respectable Women, Ambitious Men: Gender and Family Networks in Victorian Sheffield Autumn Mayle Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University In partial fulfillment for the requirement for the degree of Doctorate in History Katherine Aaslestad, Ph. D., Chair Joseph Hodge, Ph. D. Matthew Vester, Ph. D. Marilyn Francus, Ph.