Of People and Toads: Local Knowledge About Amphibians Around A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brachydactyly in the Toad Rhinella Granulosa (Bufonidae) from the Caatinga of Brazil: a Rare Case with All Limbs Affected

Herpetology Notes, volume 11: 445-448 (2018) (published online on 24 May 2018) Brachydactyly in the toad Rhinella granulosa (Bufonidae) from the Caatinga of Brazil: a rare case with all limbs affected Larissa L. Correia1,2, João P. F. A. Almeida1, Barnagleison S. Lisboa3 and Filipe A. C. Nascimento3,4,* Amphibians are unique among tetrapods due to toads and frogs (e.g. Flyaks and Borkin, 2003; Guerra their biphasic life cycle and permeable skin. These and Aráoz, 2016; Silva-Soares and Mônico, 2017). features make them sensitive to potentially dangerous While conducting a survey of Rhinella granulosa exogenous factors that can affect their development (Spix, 1824) specimens deposited in the herpetological and generate body malformations. However, some collection of the Museu de História Natural of the endogenous factors, such as gene mutations, can also Universidade Federal de Alagoas, we found a specimen be the cause of some malformations (e.g. Droin et (MUFAL 8138) with bilateral brachydactyly on the fore- al., 1970; Droin, 1992). Although common in natural and hindlimbs. We used x-ray photographs taken using populations reaching a prevalence rate of 2–5% (Lunde a dental x-ray machine Dabi Atlante Spectro II in order and Johnson, 2012), these abnormalities might affect to confirm the malformation and verify the limb bone individual fitness and thus contribute to the reduction of arrangement. Specimen identification was confirmed amphibian populations (Johnson et al., 2003). based on the diagnosis of Narvaes and Rodrigues (2009), Most cases of malformations in amphibians affect the which reviewed the taxonomy of Rhinella granulosa appendicular skeleton, mainly the bones of the limbs species group. -

Bufadienolides from the Skin Secretions of the Neotropical Toad Rhinella Alata (Anura: Bufonidae): Antiprotozoal Activity Against Trypanosoma Cruzi

molecules Article Bufadienolides from the Skin Secretions of the Neotropical Toad Rhinella alata (Anura: Bufonidae): Antiprotozoal Activity against Trypanosoma cruzi Candelario Rodriguez 1,2,3 , Roberto Ibáñez 4 , Luis Mojica 5, Michelle Ng 6, Carmenza Spadafora 6 , Armando A. Durant-Archibold 1,3,* and Marcelino Gutiérrez 1,* 1 Centro de Biodiversidad y Descubrimiento de Drogas, Instituto de Investigaciones Científicas y Servicios de Alta Tecnología (INDICASAT AIP), Apartado 0843-01103, Panama; [email protected] 2 Department of Biotechnology, Acharya Nagarjuna University, Nagarjuna Nagar, Guntur 522510, India 3 Departamento de Bioquímica, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Exactas y Tecnología, Universidad de Panamá, Apartado 0824-03366, Panama 4 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), Balboa, Ancon P.O. Box 0843-03092, Panama; [email protected] 5 Centro Nacional de Metrología de Panamá (CENAMEP AIP), Apartado 0843-01353, Panama; [email protected] 6 Centro de Biología Celular y Molecular de Enfermedades, INDICASAT AIP, Apartado 0843-01103, Panama; [email protected] (M.N.); [email protected] (C.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.A.D.-A.); [email protected] (M.G.) Abstract: Toads in the family Bufonidae contain bufadienolides in their venom, which are charac- Citation: Rodriguez, C.; Ibáñez, R.; terized by their chemical diversity and high pharmacological potential. American trypanosomiasis Mojica, L.; Ng, M.; Spadafora, C.; is a neglected disease that affects an estimated 8 million people in tropical and subtropical coun- Durant-Archibold, A.A.; Gutiérrez, M. tries. In this research, we investigated the chemical composition and antitrypanosomal activity Bufadienolides from the Skin of toad venom from Rhinella alata collected in Panama. -

Anura: Brachycephalidae) Com Base Em Dados Morfológicos

Pós-graduação em Biologia Animal Laboratório de Anatomia Comparada de Vertebrados Departamento de Ciências Fisiológicas Instituto de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade de Brasília Sistemática filogenética do gênero Brachycephalus Fitzinger, 1826 (Anura: Brachycephalidae) com base em dados morfológicos Tese apresentada ao Programa de pós-graduação em Biologia Animal para a obtenção do título de doutor em Biologia Animal Leandro Ambrósio Campos Orientador: Antonio Sebben Co-orientador: Helio Ricardo da Silva Maio de 2011 Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Biológicas Programa de Pós-graduação em Biologia Animal TESE DE DOUTORADO LEANDRO AMBRÓSIO CAMPOS Título: “Sistemática filogenética do gêneroBrachycephalus Fitzinger, 1826 (Anura: Brachycephalidae) com base em dados morfológicos.” Comissão Examinadora: Prof. Dr. Antonio Sebben Presidente / Orientador UnB Prof. Dr. José Peres Pombal Jr. Prof. Dr. Lílian Gimenes Giugliano Membro Titular Externo não Vinculado ao Programa Membro Titular Interno Vinculado ao Programa Museu Nacional - UFRJ UnB Prof. Dr. Cristiano de Campos Nogueira Prof. Dr. Rosana Tidon Membro Titular Interno Vinculado ao Programa Membro Titular Interno Vinculado ao Programa UnB UnB Brasília, 30 de maio de 2011 Dedico esse trabalho à minha mãe Corina e aos meus irmãos Flávio, Luciano e Eliane i Agradecimentos Ao Prof. Dr. Antônio Sebben, pela orientação, dedicação, paciência e companheirismo ao longo do trabalho. Ao Prof. Dr. Helio Ricardo da Silva pela orientação, companheirismo e pelo auxílio imprescindível nas expedições de campo. Aos professores Carlos Alberto Schwartz, Elizabeth Ferroni Schwartz, Mácia Renata Mortari e Osmindo Pires Jr. pelos auxílios prestados ao longo do trabalho. Aos técnicos Pedro Ivo Mollina Pelicano, Washington José de Oliveira e Valter Cézar Fernandes Silveira pelo companheirismo e auxílio ao longo do trabalho. -

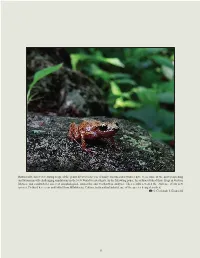

Historically, Direct-Developing Frogs of The

Historically, direct-developing frogs of the genus Eleutherodacylus (Family: Eleutherodactylidae) have been some of the most perplexing and taxonomically challenging amphibians in the New World to investigate. In the following paper, the authors studied these frogs in western Mexico, and conducted a series of morphological, molecular, and vocalization analyses. Their results revealed the existence of six new species. Pictured here is an individual from Ixtlahuacán, Colima, in its natural habitat, one of the species being described. ' © Christoph I. Grünwald 6 Grünwald et al. Six new species of Eleutherodactylus www.mesoamericanherpetology.com www.eaglemountainpublishing.com Version of record: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3EDC9AB7-94EE-4EAC-89B4-19F5218A593A Six new species of Eleutherodactylus (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae: subgenus Syrrhophus) from Mexico, with a discussion of their systematic relationships and the validity of related species CHRISTOPH I. GRÜNWALD1,2,3,6, JACOBO REYES-VELASCO3,4,6, HECTOR FRANZ-CHÁVEZ3,5,6, KAREN I. 3,6 3,5,6 2,3,6 4 MORALES-FLORES , IVÁN T. AHUMADA-CARRILLO , JASON M. JONES , AND STEPHANE BOISSINOT 1Biencom Real Estate, Carretera Chapala - Jocotepec #57-1, C.P. 45920, Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico. E-mail: [email protected] (Corresponding author) 2Herpetological Conservation International - Mesoamerica Division, 450 Jolina Way, Encinitas, California 92024, United States. 3Biodiversa A. C., Chapala, Jalisco, Mexico. 4New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. 5Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Carretera a Nogales Km. 15.5. Las Agujas, Nextipac, Zapopan, C.P. 45110, Jalisco, Mexico. 6Herp.mx A.C., Villa de Alvarez, Colima, Mexico. ABSTRACT: We present an analysis of morphological, molecular, and advertisement call data from sampled populations of Eleutherodactylus (subgenus Syrrhophus) from western Mexico and describe six new spe- cies. -

Diptera: Sarcophagidae) in Anuran of Leptodactylidae (Amphibia)

CASO CLÍNICO REVISTA COLOMBIANA DE CIENCIA ANIMAL Rev Colombiana Cienc Anim 2015; 7(2):217-220. FIRST REPORT OF MYIASIS (DIPTERA: SARCOPHAGIDAE) IN ANURAN OF LEPTODACTYLIDAE (AMPHIBIA) PRIMER REGISTRO DE MIASIS (DIPTERA: SARCOPHAGIDAE) EN ANUROS DE LEPTODACTYLIDAE (AMPHIBIA) GERSON AZULIM MÜLLER,1*Dr, CARLOS RODRIGO LEHN,1 M.Sc, ABEL BEMVENUTI,1 M.Sc, CARLOS BRISOLA MARCONDES,2 Dr. 1Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia Farroupilha, Campus Panambi, RS, Brasil. 2 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Departamento de Microbiologia e Parasitologia, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, SC, Brasil. Key words: Abstract Anura, This note is the first report of myiasis caused by Sarcophagidae flies in an anuran of Brazil, Leptodactylidae. The frog, identified asLeptodactylus latrans (Steffen, 1815), was Leptodactylus latrans, collected in Atlantic forest bioma, southern Brazil. The frog had extensive muscle parasitism. damage and orifices in the tegument caused by presence of 21 larvae, identified as Sarcophagidae. Ecological interactions between dipterans and anuran are poorly known. The impact of sarcophagid flies in anuran popuilations requires further study. Palabras Clave: Resumen Anura, Esta nota es el primer registro de ocurrencia de miasis generada por moscas Brasil, Sarcophagidae en anuro de la familia Leptodactylidae. El anfibio, identificado Leptodactylus latrans, como Leptodactylus latrans (Steffen, 1815), fue recolectado en el bioma Mata parasitismo. Atlântica, en el sur de Brasil. La rana presentaba extensas lesiones musculares y orificios en el tegumento generados por la presencia de 21 larvas, identificadas como Sarcophagidae. Las interacciones ecológicas entre insectos dípteros y anuros son poco conocidas. El impacto de las moscas Sarcophagidae en las poblaciones de anuros requiere más estudio. -

New Species of the Rhinella Crucifer Group (Anura, Bufonidae) from the Brazilian Cerrado

Zootaxa 3265: 57–65 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) New species of the Rhinella crucifer group (Anura, Bufonidae) from the Brazilian Cerrado WILIAN VAZ-SILVA1,2,5, PAULA HANNA VALDUJO3 & JOSÉ P. POMBAL JR.4 1 Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Centro Universitário de Goiás – Uni-Anhanguera, Rua Professor Lázaro Costa, 456, CEP: 74.415-450 Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 2 Laboratório de Genética e Biodiversidade, Departamento de Biologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Campus Samambaia, Cx. Postal 131 CEP: 74.001-970, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 3 Departamento de Ecologia. Universidade de São Paulo. Rua do Matão, travessa 14. CEP: 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 4 Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Vertebrados, Museu Nacional, Quinta da Boa Vista, CEP: 20940-040, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 5 Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species of Rhinella of Central Brazil from the Rhinella crucifer group is described. Rhinella inopina sp. nov. is restricted to the disjunct Seasonal Tropical Dry Forests enclaves in the western Cerrado biome. The new species is characterized mainly by head wider than long, shape of parotoid gland, and oblique arrangement of the parotoid gland. Data on natural history and distribution are also presented. Key words: Rhinella crucifer group, Seasonally Dry Forest, Cerrado, Central Brazil Introduction The cosmopolitan Bufonidae family (true toads) presented currently 528 species. The second most diverse genus of Bufonidae, Rhinella Fitzinger 1826, comprises 77 species, distributed in the Neotropics and some species were introduced in several world locations (Frost 2011). -

Release Calls of Four Species of Phyllomedusidae (Amphibia, Anura)

Herpetozoa 32: 77–81 (2019) DOI 10.3897/herpetozoa.32.e35729 Release calls of four species of Phyllomedusidae (Amphibia, Anura) Sarah Mângia1, Felipe Camurugi2, Elvis Almeida Pereira1,3, Priscila Carvalho1,4, David Lucas Röhr2, Henrique Folly1, Diego José Santana1 1 Mapinguari – Laboratório de Biogeografia e Sistemática de Anfíbios e Repteis, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, 79002-970, Campo Grande, MS, Brazil. 2 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Lagoa Nova, 59072-970, Natal, RN, Brazil. 3 Programa de Pós-graduação em Biologia Animal, Laboratório de Herpetologia, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, 23890-000, Seropédica, RJ, Brazil. 4 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), 15054-000, São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil. http://zoobank.org/16679B5D-5CC3-4EF1-B192-AB4DFD314C0B Corresponding author: Sarah Mângia ([email protected]) Academic editor: Günter Gollmann ♦ Received 8 January 2019 ♦ Accepted 6 April 2019 ♦ Published 15 May 2019 Abstract Anurans emit a variety of acoustic signals in different behavioral contexts during the breeding season. The release call is a signal produced by the frog when it is inappropriately clasped by another frog. In the family Phyllomedusidae, this call type is known only for Pithecophus ayeaye. Here we describe the release call of four species: Phyllomedusa bahiana, P. sauvagii, Pithecopus rohdei, and P. nordestinus, based on recordings in the field. The release calls of these four species consist of a multipulsed note. Smaller species of the Pithecopus genus (P. ayeaye, P. rohdei and P. nordestinus), presented shorter release calls (0.022–0.070 s), with high- er dominant frequency on average (1508.8–1651.8 Hz), when compared to the bigger Phyllomedusa (P. -

Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service 2012 Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae) Christina A. Olson Utah State University, [email protected] Karen H. Beard Utah State University, [email protected] William C. Pitt National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Olson, Christina A.; Beard, Karen H.; and Pitt, William C., "Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae)" (2012). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 1174. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/1174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 8. Eleutherodactylus planirostris, the Greenhouse Frog (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae)1 Christina A. Olson,2 Karen H. Beard,2,4 and William C. Pitt 3 Abstract: The greenhouse frog, Eleutherodactylus planirostris, is a direct- developing (i.e., no aquatic stage) frog native to Cuba and the Bahamas. It was introduced to Hawai‘i via nursery plants in the early 1990s and then subsequently from Hawai‘i to Guam in 2003. The greenhouse frog is now widespread on five Hawaiian Islands and Guam. -

Herpetological Review

Herpetological Review Volume 41, Number 2 — June 2010 SSAR Offi cers (2010) HERPETOLOGICAL REVIEW President The Quarterly News-Journal of the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles BRIAN CROTHER Department of Biological Sciences Editor Southeastern Louisiana University ROBERT W. HANSEN Hammond, Louisiana 70402, USA 16333 Deer Path Lane e-mail: [email protected] Clovis, California 93619-9735, USA [email protected] President-elect JOSEPH MENDLELSON, III Zoo Atlanta, 800 Cherokee Avenue, SE Associate Editors Atlanta, Georgia 30315, USA e-mail: [email protected] ROBERT E. ESPINOZA KERRY GRIFFIS-KYLE DEANNA H. OLSON California State University, Northridge Texas Tech University USDA Forestry Science Lab Secretary MARION R. PREEST ROBERT N. REED MICHAEL S. GRACE PETER V. LINDEMAN USGS Fort Collins Science Center Florida Institute of Technology Edinboro University Joint Science Department The Claremont Colleges EMILY N. TAYLOR GUNTHER KÖHLER JESSE L. BRUNNER Claremont, California 91711, USA California Polytechnic State University Forschungsinstitut und State University of New York at e-mail: [email protected] Naturmuseum Senckenberg Syracuse MICHAEL F. BENARD Treasurer Case Western Reserve University KIRSTEN E. NICHOLSON Department of Biology, Brooks 217 Section Editors Central Michigan University Mt. Pleasant, Michigan 48859, USA Book Reviews Current Research Current Research e-mail: [email protected] AARON M. BAUER JOSHUA M. HALE BEN LOWE Department of Biology Department of Sciences Department of EEB Publications Secretary Villanova University MuseumVictoria, GPO Box 666 University of Minnesota BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia St Paul, Minnesota 55108, USA P.O. Box 58517 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Salt Lake City, Utah 84158, USA e-mail: [email protected] Geographic Distribution Geographic Distribution Geographic Distribution Immediate Past President ALAN M. -

Amphibia: Anura: Eleutherodactylidae), from Eastern Cuba

124 SOLENODON 12: 124-135, 2015 Another new cryptic frog related to Eleutherodactylus varleyi Dunn (Amphibia: Anura: Eleutherodactylidae), from eastern Cuba Luis M. DÍAZ* and S. Blair HEDGES** *Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Cuba, Obispo #61, Esquina Oficios, Plaza de Armas, Habana Vieja, CP 10100, Cuba. [email protected] **Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802-530, USA. [email protected] ABSTRacT. A new cryptic frog, Eleutherodactylus beguei sp. nov., is described from the pine forests of La Munición, Yateras, Guantánamo Province, Cuba. It is sympatric with E. feichtin- geri, another recently described grass frog closely related to E. varleyi, but differs in morphol- ogy, vocalization and DNA sequences of the mitochondrial Cyt-b gene. One female of the new species was found vocalizing in response to a calling male, a behavior that is still poorly documented in anurans. Same male and female were found in axillary amplexus and sur- rounded by 9 eggs (3.5–3.7 mm in diameter) 5 hours after being isolated in a small container. Key words: Amphibia, Anura, Eleutherodactylidae, Eleutherodactylus, new species, Terrarana, Euhyas, West Indies, Guantánamo, female reciprocation calls, eggs. INtrODUCtION After a recent review of the geographic variation of the Cuban Grass Frog Eleutherodactylus varleyi Dunn, Díaz et al. (2012) described E. feichtingeri, a cryptic species widely distributed in central and eastern Cuba. the two species differ primarily in tympanum size, supratympanic stripe pattern, and advertisement calls. Species recognition was also supported by genetic and cytogenetic data. One of the authors (SBH) conducted DNA sequence analyses that confirmed the existence of two species at La Munición, Humboldt National Park. -

Polyploidy and Sex Chromosome Evolution in Amphibians

Chapter 18 Polyploidization and Sex Chromosome Evolution in Amphibians Ben J. Evans, R. Alexander Pyron and John J. Wiens Abstract Genome duplication, including polyploid speciation and spontaneous polyploidy in diploid species, occurs more frequently in amphibians than mammals. One possible explanation is that some amphibians, unlike almost all mammals, have young sex chromosomes that carry a similar suite of genes (apart from the genetic trigger for sex determination). These species potentially can experience genome duplication without disrupting dosage stoichiometry between interacting proteins encoded by genes on the sex chromosomes and autosomalPROOF chromosomes. To explore this possibility, we performed a permutation aimed at testing whether amphibian species that experienced polyploid speciation or spontaneous polyploidy have younger sex chromosomes than other amphibians. While the most conservative permutation was not significant, the frog genera Xenopus and Leiopelma provide anecdotal support for a negative correlation between the age of sex chromosomes and a species’ propensity to undergo genome duplication. This study also points to more frequent turnover of sex chromosomes than previously proposed, and suggests a lack of statistical support for male versus female heterogamy in the most recent common ancestors of frogs, salamanders, and amphibians in general. Future advances in genomics undoubtedly will further illuminate the relationship between amphibian sex chromosome degeneration and genome duplication. B. J. Evans (CORRECTED&) Department of Biology, McMaster University, Life Sciences Building Room 328, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, ON L8S 4K1, Canada e-mail: [email protected] R. Alexander Pyron Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G St. NW, Washington, DC 20052, USA J. -

Amphibians from the Centro Marista São José Das Paineiras, in Mendes, and Surrounding Municipalities, State of Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

Herpetology Notes, volume 7: 489-499 (2014) (published online on 25 August 2014) Amphibians from the Centro Marista São José das Paineiras, in Mendes, and surrounding municipalities, State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Manuella Folly¹ *, Juliana Kirchmeyer¹, Marcia dos Reis Gomes¹, Fabio Hepp², Joice Ruggeri¹, Cyro de Luna- Dias¹, Andressa M. Bezerra¹, Lucas C. Amaral¹ and Sergio P. de Carvalho-e-Silva¹ Abstract. The amphibian fauna of Brazil is one of the richest in the world, however, there is a lack of information on its diversity and distribution. More studies are necessary to increase our understanding of amphibian ecology, microhabitat choice and use, and distribution of species along an area, thereby facilitating actions for its management and conservation. Herein, we present a list of the amphibians found in one remnant area of Atlantic Forest, at Centro Marista São José das Paineiras and surroundings. Fifty-one amphibian species belonging to twenty-five genera and eleven families were recorded: Anura - Aromobatidae (one species), Brachycephalidae (six species), Bufonidae (three species), Craugastoridae (one species), Cycloramphidae (three species), Hylidae (twenty-four species), Hylodidae (two species), Leptodactylidae (six species), Microhylidae (two species), Odontophrynidae (two species); and Gymnophiona - Siphonopidae (one species). Visits to herpetological collections were responsible for 16 species of the previous list. The most abundant species recorded in the field were Crossodactylus gaudichaudii, Hypsiboas faber, and Ischnocnema parva, whereas the species Chiasmocleis lacrimae was recorded only once. Keywords: Anura, Atlantic Forest, Biodiversity, Gymnophiona, Inventory, Check List. Introduction characteristics. The largest fragment of Atlantic Forest is located in the Serra do Mar mountain range, extending The Atlantic Forest extends along a great part of from the coast of São Paulo to the coast of Rio de Janeiro the Brazilian coast (Bergallo et al., 2000), formerly (Ribeiro et al., 2009).