Prevalence and Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression, General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study at KEK Look Tong Cave, Perak

International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology Vol. 29, No. 1, (2020), pp. 1435- 1454 Cave Stability and Sustainable Development: A Case Study At KEK Look Tong Cave, Perak 1Ailie Sofyiana Serasa, 2Goh Thian Lai, 2Nur Amanina Mazlan 1School of Engineering, Asia Pacific University of Technology & Innovation, 57000 Bukit Jalil, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2Geology Program, Center of Earth Science and Environment, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor Abstract The beauty of karst terrains of limestone caves attracts many tourists due to its unique architecture. In Malaysia, some of the caves have been converted into religion caverns. However there is no systematic guideline to evaluate the stability and sustainability of the cave and cave wall. This research paper presents a systematic approach for the assessment of limestone cave stability using Q system and Slope Mass Rating (SMR) at Kek Look Tong, Perak. Based on the assessment of Slope Mass Rating (SMR), the entire cave walls were classified from class II to IV. The cave walls without potential failure were classified into class II. 10 out of 33 cave walls were identified to have potential wedge and planar failure with the SMR score from 36 to 78.5. The cave wall of GR2-1 and GR2-2 were classified as class II to III (stable to partially stable) and class II (stable) respectively. The cave wall of GR4-2, GR4-6, GR4-8 and GR4-9 were classified as class II (stable). The cave wall GR4-4 was classified as class III (partially stable). Cave wall of GR4-1 was classified as class IV (unstable). -

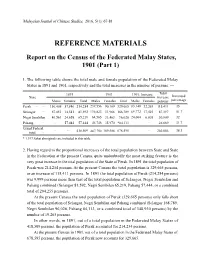

REFERENCE MATERIALS Report on the Census of the Federated Malay

Malaysian Journal of Chinese Studies, 2016, 5(1): 67-81 REFERENCE MATERIALS Report on the Census of the Federated Malay States, 1901 (Part 1) 1. The following table shows the total male and female population of the Federated Malay States in 1891 and 1901, respectively and the total increases in the number of persons: — 1891 1901 1901, Increase Total State increase Increased Males Females Total Males Females Total Males Females persons percentage Perak … … 156,408 57,846 214,254 239,556 90,109 329,665 83,148 32,263 115,411 35 Selangor … 67,051 14,541 81,592 136,823 31,966 168,789 69,772 17,425 87,197 51.7 Negri Sembilan 40,561 24,658 65,219 64,565 31,463 96,028 24,004 6,805 30,809 32 Pahang … … 57,444 57,444 46,746 35,970 *84,113 … … 26,669 31.7 Grand Federal … … 418,509 487,790 189,508 678,595 … … 260,086 38.3 total … * 1,397 Sakai aboriginals are included in this table. 2. Having regard to the proportional increases of the total population between State and State in the Federation at the present Census, quite undoubtedly the most striking feature is the very great increase in the total population of the State of Perak. In 1891 the total population of Perak was 214,254 persons. At the present Census the total population is 329,665 persons, or an increase of 115,411 persons. In 1891 the total population of Perak (214,254 persons) was 9,999 persons more than that of the total population of Selangor, Negri Sembilan and Pahang combined (Selangor 81,592, Negri Sembilan 65,219, Pahang 57,444, or a combined total of 204,255 persons). -

No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Taiping 15 16 17 NEGERI PERAK

NEGERI PERAK SENARAI TAPAK BEROPERASI : 17 TAPAK Tahap Tapak No Kawasan PBT Nama Tapak Alamat Tapak (Operasi) 1 Batu Gajah TP Batu Gajah Batu 3, Jln Tanjung Tualang, Batu Gajah Bukan Sanitari Jalan Air Ganda Gerik, Perak, 2 Gerik TP Jln Air Ganda Gerik Bukan Sanitari D/A MDG 33300 Gerik, Perak Batu. 8, Jalan Bercham, Tanjung 3 Ipoh TP Bercham Bukan Sanitari Rambutan, Ipoh, Perak Batu 21/2, Jln. Kuala Dipang, Sg. Siput 4 Kampar TP Sg Siput Selatan Bukan Sanitari (S), Kampar, Perak Lot 2720, Permatang Pasir, Alor Pongsu, 5 Kerian TP Bagan Serai Bukan Sanitari Beriah, Bagan Serai KM 8, Jalan Kuala Kangsar, Salak Utara, 6 Kuala Kangsar TP Jln Kuala Kangsar Bukan Sanitari Sungai Siput 7 Lenggong TP Ayer Kala Lot 7345 & 7350, Ayer Kala, Lenggong Bukan Sanitari Batu 1 1/2, Jalan Beruas - Sitiawan, 8 Manjung TP Sg Wangi Bukan Sanitari 32000 Sitiawan 9 Manjung TP Teluk Cempedak Teluk Cempedak, Pulau Pangkor Bukan Sanitari 10 Manjung TP Beruas Kg. Che Puteh, Jalan Beruas - Taiping Bukan Sanitari Bukit Buluh, Jalan Kelian Intan, 33100 11 Pengkalan Hulu TP Jln Gerik Bukan Sanitari Pengkalan Hulu 12 Perak Tengah TP Parit Jln Chopin Kanan, Parit Bukan Sanitari 13 Selama TP Jln Tmn Merdeka Kg. Lampin, Jln. Taman Merdeka, Selama Bukan Sanitari Lot 1706, Mukim Jebong, Daerah Larut 14 Taiping TP Jebong Bukan Sanitari Matang dan Selama Kampung Penderas, Slim River, Tanjung 15 Tanjung Malim TP Penderas Bukan Sanitari Malim 16 Tapah TP Bidor, Pekan Pasir Kampung Baru, Pekan Pasir, Bidor Bukan Sanitari 17 Teluk Intan TP Changkat Jong Batu 8, Jln. -

Q1FY13 MY Stores Database.Xlsx

Dealer Name Location Address Contact Number Fax Number 5G GALLERY (SNS NETWORK (M) SDN BHD) PERAK 3RD FLOOR, IPOH PARADE SHOPPING CENTER, 30450, IPOH PERAK 05-2424222 - BIOSYS SOLUTION SDN BHD PERAK No 18-2 FLOOR, LORONG MELOR I, TAMAN MELOR III, 36000, TELUK INTAN PERAK. 05-6236303 05-6223525 BIOSYS SOLUTION SDN BHD PERAK SF4-7, 2ND FLOOR, KOMPLEKS YIK FOONG, JALAN LAXAMANA, 30300, IPOH, PERAK ETIKA KOMPUTER SDN BHD PERAK WISMA ETIKA, NO 9, MEDAN BENDAHARA 2, 31650, JERTEH, PERAK KIASU COMPUTERS SDN BHD PERAK KIASU COMPUTERS SDN BHD, TINGKAT BAWAH WISMA BOUGAINVILLEA, JALAN FOO CHOO CHOON, 30300, IPOH PERAK. KIASU COMPUTERS SDN BHD PERAK SF 22,23,24, 2ND FLOOR, KOMPLEKS YIK FOONG, JALAN LAXAMANA, IPOH, 30300, PERAK. MAGNETONE MEDIAWORLD (M) SDN BHD (PG) PERAK 33, JALAN PANGGUNG WAYANG, 34000, TAIPING PERAK. 05-73576357 MCSYSTEMS TECHNOLOGY CONSULTANS SDN BHD PERAK 206& 206A JALAN BERCHAM TAMAN RIA, 31400, IPOH, PERAK 05-55468787 05-5478641 PKU TECHNOLOGY (KL) SDN BHD PERAK NO. 15, MEDAN IPOH 1A, MEDAN IPOH BISTARI, 31400 IPOH, PERAK 05-5478816 REDCOM PERAK SF1/58/59, YIK FOONG COMPLEX, JALAN LAXAMANA, IPOH, 30300, PERAK. 05-2429788 05-2438913 REDCOM PERAK 47 JALAN MEDAN IPOH 1A, MEDAN IPOH BISTARI, IPOHM 31400, PERAK. 05-5484166 05-5484166 SECAM SURVEILLANCE PERAK GK-22A, MEGAMALL PENANG , BAGAN SERAI, PERAK SNIPER TECHNOLOGY SDN BHD (ETIKA) PERAK TF30-33 & 5-6, 3RD FLOOR, YIK FOONG COMPLEKS JALAN LAXAMANA, 30300, IPOH, PERAK. SNS NETWORK (M) SDN BHD PERAK MULTIMEDIA DEPARTMENT, JUSCO KINTA CITY, 31400, IPOH, PERAK 05-5484616 - SNS NETWORK (M) SDN BHD PERAK 20, PERSIARAN GREENTOWN 1, GREENTOWN BUSINESS CENTRE, GREENTOWN, 30450, IPOH, PERAK 05-242 4616 - SNS NETWORK (M) SDN BHD PERAK JUSCO STATION 18, 14000, IPOH, PERAK WAH LEE GROUP ELECTRICAL APPLIANCES PERAK WAH LEE : 5 & 7, JALAN HARMONI, PUSAT BANDAR, BAGAN SERAI, PERAK WAH LEE GROUP ELECTRICAL APPLIANCES PERAK WAH LEE : 25, 27 & 29, JALAN MERBUK 1, TAMAN PEKAN BARU, 34200, PARIT BUNTAR PERAK WAH LEE GROUP ELECTRICAL APPLIANCES PERAK 2369A, LORONG SENA OFF LEBUHRAYA DARULAMAN, 05100 ALOR SETAR, KEDAH. -

Issue 3/2015

Issue 3/2015 Students in the Power and Control Labaratory 02 Collaborations at Work 07 10 12 14 16 18 20 02 Collaborations at Work 03 TAR was visited by the High UCommisioner of Uganda at Petaling Council Chairman visits Schools Jaya Campus on 12 May 2015. Visit by High TAR Council-cum-Malaysia The delegation was led by the High UMental Literacy Movement Commisioner of Uganda, His Excellency (MMLM) Chairman Tun Dr Stephen Mubiru accompanied by the First Commisioner of Uganda Ling Liong Sik led a delegation Secretary Mbabazi Samantha Sherurah. On to visit nine secondary schools hand to welcome the guests were UTAR leaders. He further expressed desire for on 27 and 28 April; and 11, 14, President Ir Prof Academician Dato’ Dr “I consider this an important day in our continued collaboration, including the 15 and 28 May 2015. Passionate Chuah Hean Teik, Vice President for R&D lives, as we have place a key into the door possibility of setting up an exchange visits about affordable education and and Commercialisation Prof Ir Dr Lee Sze that opens up to great possibilities in the for staff and students from UTAR and mental literacy for all, the visits Wei, Institute of Postgraduate Studies and future,” said Mubiru with a smile. universities in Uganda. were a continuation of the Teach Research Director Prof Dr Faidz bin Abd “We have a lot to learn from Malaysia To date, UTAR houses one international For Malaysia (TFM) school visits Rahman, Division of Programme Promotion when it comes to technology application,” he student from Uganda who is undertaking the of 2014. -

The Perak Development Experience: the Way Forward

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences December 2013, Vol. 3, No. 12 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Perak Development Experience: The Way Forward Azham Md. Ali Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Management and Economics Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 Speech for the Menteri Besar of Perak the Right Honourable Dato’ Seri DiRaja Dr Zambry bin Abd Kadir to be delivered on the occasion of Pangkor International Development Dialogue (PIDD) 2012 I9-21 November 2012 at Impiana Hotel, Ipoh Perak Darul Ridzuan Brothers and Sisters, Allow me to briefly mention to you some of the more important stuff that we have implemented in the last couple of years before we move on to others areas including the one on “The Way Forward” which I think that you are most interested to hear about. Under the so called Perak Amanjaya Development Plan, some of the things that we have tried to do are the same things that I believe many others here are concerned about: first, balanced development and economic distribution between the urban and rural areas by focusing on developing small towns; second, poverty eradication regardless of race or religion so that no one remains on the fringes of society or is left behind economically; and, third, youth empowerment. Under the first one, the state identifies viable small- and medium-size companies which can operate from small towns. These companies are to be working closely with the state government to boost the economy of the respective areas. -

ARE WE ASHAMED of IPOH’S GLORIOUS PAST? by Jerry Francis “City That Tin Built” – About Sums up the History of Ipoh and Its Heritage

www.ipohecho.com.my JUNE 1 DEADLINE If you want to continue receiving the Ipoh Echo every fortnight with your daily newspaper, please IPOH inform your newsvendor. echoYour Voice In The Community See box on the right. echo May 16-31, 2010 PP 14252/10/2010(025567) FREE COPY ISSUE 97 rom 1st June please inform your news vendor to deliver the >> Pg 3 >> Pg 4 FIpoh Echo every fortnight if you wish to continue receiving your community paper. We are still a free paper. To help us defray PROTECTING THE LET’S NOT REMAIN INNOCENTS our distribution costs, we’re asking you, dear reader, to pay your A BACKWATER news vendor 30¢ per issue for delivery, i.e., a cost of 60¢ per month. A small sum for you to keep up with the latest news and information of your Ipoh community. Thank you for your continuing support of the Ipoh Echo – Your Voice of the Ipoh Community. ARE WE ASHAMED OF IPOH’S GLORIOUS PAST? By Jerry Francis “City That Tin Built” – about sums up the history of Ipoh and its heritage. These four words are also an effective slogan to promote the city. Not “Bougainvillea City” or by any other slogans. On May 27 Ipoh will celebrate its 22nd anniversary as a city. But it is sad that through all those years nothing seems to have been done to reflect its glorious past as the centre of the tin mining industry which had been so significant in the economic development of the country. The tin mining industry has since collapsed; the history of the city will also slowly fade away and be forgotten. -

190531 SAM Annual Report 2018 F

SAHABAT ALAM MALAYSIA (SAM) ANNUAL REPORT 2018 No. 1 Jalan Joki, 11400 Penang Tel: +604 827 6 930 Fax: +604 827 6 932 ACKNOWLEDGMENT SAM would like to thank all staff, members, volunteers, friends, donors, funders and the media for all your support. SAM would like to thank Amelia Collins of FoEI and all SAM staff for graciously allowing us to use their photographs for this report. !2 SAM ANNUAL REPORT 2018 IN A NUTSHELL 2018 was a significant year for Malaysia, with the national elections that changed the political landscape of the country. The non stop myriad of activities under various projects from the beginning of the year kept all SAM staff busy. Some of the major issues SAM handled in 2018 included: Lynas - to remove radioactive waste from Malaysia Plastic waste trade and dumping Reclamation projects - proposed and ongoing (Penang, Perak, Kedah) Road projects in Penang - PIL1, three major roads Development on hill slopes in Penang, Perak, Kedah, etc SAM’s main activities in 2018 were carried out Our activities included conducting awareness Trawler encroachments into coastal fishing under the following work heads: zone raising programmes among rural and local Land rights of indigenous communities in communities, meeting and having dialogues Protection and conservation of forest and Sarawak & Peninsular Malaysia with local, state and federal authorities, coastal ecosystems; Expansion of plantations and development workshop on constructing fishing gears, Defending indigenous communities of monoculture plantations in permanent preparing -

Cadangan Surau-Surau Dalam Daerah Untuk Solat Jumaat Sepanjang Pkpp

JAIPK/BPM/32/12 Jld.2 ( ) CADANGAN SURAU-SURAU DALAM DAERAH UNTUK SOLAT JUMAAT SEPANJANG PKPP Bil DAERAH BILANGAN SURAU SOLAT JUMAAT 1. PARIT BUNTAR 3 2. TAIPING 8 3. PENGKALAN HULU 2 4. GERIK 8 5. SELAMA 4 6. IPOH 25 7. BAGAN SERAI 2 8. KUALA KANGSAR 6 9. KAMPAR 4 10. TAPAH 6 11. LENGGONG 4 12. MANJUNG 3 13. SERI ISKANDAR 5 14. BATU GAJAH 2 15. BAGAN DATUK Tiada cadangan 16. KAMPUNG GAJAH 1 17. MUALLIM 4 18. TELUK INTAN 11 JUMLAH 98 JAIPK/BPM/32/12 Jld.2 ( ) SURAU-SURAU DALAM NEGERI PERAK UNTUK SOLAT JUMAAT SEPANJANG TEMPOH PKPP DAERAH : PARIT BUNTAR BIL NAMA DAN ALAMAT SURAU 1. Surau Al Amin, Parit Haji Amin, Jalan Baharu, 34200 Parit Buntar, Perak Surau Al Amin Taman Murni, 2. Kampung Kedah, 34200 Parit Buntar, Perak Surau Ar Raudah, 3 Taman Desa Aman, 34200, Parit Buntar, Perak DAERAH : TELUK INTAN BIL NAMA DAN ALAMAT SURAU 1. Surau Al Huda, Taman Pelangi, 36700 Langkap, Perak 2. Madrasah Al Ahmadiah, Perumaham Awam Padang Tembak, 36000 Teluk Intan, Perak 3. Surau Taman Saujana Bakti, Taman Saujana Bakti, Jalan Maharajalela, 36000 Teluk Intan, Perak 4. Surau Taman Bahagia, Kampung Bahagia, 36000 Teluk Intan, Perak. 5. Surau Al Khairiah, Lorong Jasa, Kampung Padang Tembak, 36000 Teluk Intan, Perak. 6. Surau Al Mujaddid, Taman Padang Tembak, 36000 Teluk Intan, Perak. 7. Surau Taufiqiah, Padang Tembak, 36000 Teluk Intan, Perak 8. Surau Tul Hidayah, Kampung Tersusun, Kampung Padang Tembak Dalam, 36000 Teluk Intan, Perak Surau Al Mudassir, 9. RPA 4, Karentina', Batu 3 1/2, Kampung Batak Rabit, 36000 Teluk Intan, Perak Surau Kolej Vokasional ( Pertanian ) Teluk Intan, 10. -

Data Standardization Analysis to Form Geo-Demographics Classification Profiles Using K-Means Algorithms

GEOGRAFIA OnlineTM Malaysian Journal of Society and Space 12 issue 6 (34 - 42) 34 Themed issue on current social, economic, cultural and spatial dynamics of Malaysia’s transformation © 2016, ISSN 2180-2491 Improving the tool for analyzing Malaysia’s demographic change: Data standardization analysis to form geo-demographics classification profiles using k-means algorithms Kamarul Ismail1, Nasir Nayan1, Siti Naielah Ibrahim1 1Jabatan Geografi dan Alam Sekitar, Fakulti Sains Kemanusiaan, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, 35900 Tanjong Malim, Perak Correspondence: Kamarul Ismail (email: [email protected]) Abstract Clustering is one of the important methods in data exploratory in this era because it is widely applied in data mining.Clustering of data is necessary to produce geo-demographic classification where k-means algorithm is used as cluster algorithm. K-means is one of the methods commonly used in cluster algorithm because it is more significant. However, before any data are executed on cluster analysis it is necessary to conduct some analysis to ensure the variable used in the cluster analysis is appropriate and does not have a recurring information. One analysis that needs to be done is the standardization data analysis. This study observed which standardization method was more effective in the analysis process of Malaysia’s population and housing census data for the Perak state. The rationale was that standardized data would simplify the execution of k-means algorithm. The standardized methods chosen to test the data accuracy were the z-score and range standardization method. From the analysis conducted it was found that the range standardization method was more suitable to be used for the data examined. -

Malaysia (Including Borneo)

Destination Information Guide Malaysia (Including Borneo) Big Five Tours & Expeditions, USA Big Five Tours & Expeditions Ltd. Canada 1551 SE Palm Court, Stuart, FL 34994 80 Corporate Drive Unit 311 Tel: 772-287-7995 / Fax: 772-287-5990 Scarborough, Ontario M1H 3G5 Canada 800 BIG FIVE (800-244-3483) Tel: +416-640-7802 / Fax: 1-647-463-8181 www.bigfive.com & www.galapagos.com Toll Free: 888- 244-3483 Email: [email protected] www.bigfivetours.ca Email: [email protected] Welcome to the World of Big Five! The following general outline offers practical information, suggestions and answers to some frequently asked questions. It is not intended to be the definitive guide for your trip. Big Five Tours & Expeditions is pleased to welcome you on this exciting adventure. We take great care to insure that your travel dreams and expectations are well met. Our distinctive journeys allow you to experience the finest aspects each destination has to offer. We also aim to provide you with a deeper understanding of and appreciation for the places you’ll visit and the people you’ll meet. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Elevation: 72 feet Latitude: 03 07N Longitude: 101 33E Average Temperature Years on Record: 21 YEAR Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May Jun. Jul. Aug. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. °F 82 81 82 82 83 83 82 82 82 82 82 81 81 Average High Temperature Years on Record: 21 YEAR Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May Jun. Jul. Aug. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec. °F 89 89 90 91 90 90 90 89 89 89 89 88 88 Average Low Temperature Years on Record: 21 YEAR Jan. -

Property Market Review 2018 / 2019 Contents

PROPERTY MARKET REVIEW 2018 / 2019 CONTENTS Foreword Property Northern 02 04 Market 07 Region Snapshot Central Southern East Coast 31 Region 57 Region 75 Region East Malaysia The Year Glossary 99 Region 115 Ahead 117 This publication is prepared by Rahim & Co Research for information only. It highlights only selected projects as examples in order to provide a general overview of property market trends. Whilst reasonable care has been exercised in preparing this document, it is subject to change without notice. Interested parties should not rely on the statements or representations made in this document but must satisfy themselves through their own investigation or otherwise as to the accuracy. This publication may not be reproduced in any form or in any manner, in part or as a whole, without writen permission from the publisher, Rahim & Co Research. The publisher accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or to any party for reliance on the contents of this publication. 2 FOREWORD by Tan Sri Dato’ (Dr) Abdul Rahim Abdul Rahman 2018 has been an eventful year for all Malaysians, as Speed Rail) project. This move was lauded by the World witnessed by Pakatan Harapan’s historical win in the 14th Bank, who is expecting Malaysia’s economy to expand at General Election. The word “Hope”, or in the parlance of 4.7% in 2019 and 4.6% in 2020 – a slower growth rate in the younger generation – “#Hope”, could well just be the the short term as a trade-off for greater stability ahead, theme to aptly define and summarize the current year and as the nation addresses its public sector debt and source possibly the year ahead.