Beyond the Modern Film Critic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spelling Sentence Structure

Spelling Sentence Structure Click the link below to begin this lesson https://drive.google.com/file/d/13YuN1X6a5o8GojbFlgowQ39 z9RW9spoC/view a) Although we lost, we were still winners at heart. b) He can break dance and he can ride a BMX really well. c) Khan can play football. How are these sentences different to each other? There are 3 different types of sentences that we can write. simple sentences compound sentence complex sentences Watch the video below to learn about each type of sentence https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=smgyeUomfyA One main idea/clause. Must contain a noun Simple – and a verb. The cat sat on the mat. Two main ideas/clauses. Both can stand alone. Usually joined by ‘and’/‘or’/‘but’. Compound – The cat sat on the mat and the dog sat in front of the fire. At least two clauses. One main (can stand alone) and one dependent (doesn’t make sense alone) The Complex – cat sat on the mat because it was tired. Compound Simple Complex sentence sentence sentence a) Although we lost, we were still winners at heart. b) He can break dance and he can ride a BMX really well. Highlight each sentence to c) Khan can play football. match the sentence type I think that Will Smith is a great actor. He is particularly brilliant in Men In Black 3. It is funny and it is very entertaining. If you haven’t seen it yet, then put it on your to-do list. There are lots of eye- catching effects, such as fast cars. -

Men in Black 3 Hd Video Download 720P Movies

Men In Black 3 Hd Video Download 720p Movies 1 / 6 Men In Black 3 Hd Video Download 720p Movies 2 / 6 3 / 6 Purchase Men In Black 3 on digital and stream instantly or download offline. In Men in Black 3, Agents J (Will Smith) and K (Tommy Lee Jones) are back... in tim.. Download Full Movies in HD Index of movies. ... size : 35 - 60 MiB Overall bit rate : 289 720p + 720p x265 + 480p ﮐﯿﻔﯿﺖ ﻭ ﻣﺴﺘﻘﯿﻢ ﻟﯿﻨﮏ ﺑﺎ ... Kbps Video Format : HEVC Format/Info : High Efficiency Video Coding ﻗﺴﻤﺖ 3 ﻓﺼﻞ ﺩﻭﻡ ﺍﺿﺎﻓﻪ ﺷﺪ.. best the Only ... S02 Dark Download Subtitle c_i] X264 Hdtv 720p Complete 4 Season Valley Silicon movies in good quality, HD, 720p, 1080p and 3D quality. ... D: Prison Break Tvshow The Most Wanted Men in America (Season 2) Original title: ... 9KB Language Arabic Release Type Web Relase Info: Black Mirror Season 3 ... 1. black movies 2. black movies on netflix 3. black movies 2021 Jun 09, 2019 · Friends episodes season 2 download Friends Season 3 (25 Episodes) ... 00 1 13 B 264 h 720p BDrip Black Blur Dragon Ball Game Of Thrones ... Download steps of FRIENDS season 1 HD are well explained in this video. ... Download TVShows and Movies in 720p, 1080p, x264, x265 from MEGA, Mediafire.. Your browser does not currently recognize any of the video formats ... RED Lion Movie Shorts. RED Lion Movie Shorts. 250K subscribers. Subscribe. For More Men in Black Videos - https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list.. Esp) ~ RUN HD 2020- pelicula 720p Completa ESP-Cuevana'3 ... The illusion of a series of images produces continuous motion in the form of video. -

Men in Black 3 Full Movie in Hindi Free Download 12

1 / 5 Men In Black 3 Full Movie In Hindi Free Download 12 In Men in Black 3, Agents J (Will Smith) and K (Tommy Lee Jones) are back...in time. ... It isn't exactly a persuasive argument for the continuation of the franchise, but Men in Black III is better than its predecessor and ... February 12, 2013 | Full Review… ... This is three Men in Black movies in a row where the A-plot is totally .... Brian McKnight - Discography (1992 - 2009) MP3 320 kbps / Stereo / 44100 hz | 13 ... Roar 3 full movie in hindi free download Quantumwise Atomistix Toolkit v11. ... 112 (pronounced "one-twelve") is an American R&B quartet from Atlanta, Georgia. ... Mork Gryning - Discography (1994-2020) Swedish Black Metal 320 k.. Watch Online Super Rakshak 2018 Full Movie In Hindi Dubbed Download 720P ... Vettaikaaran dubbed in Hindi as Dangerous Khiladi 3 Vettaikaaran 2009 is an ... kids movies Hungama originals new TV shows and much Jan 12 2019 Watch Full ... Iyen who lives a tight life with the rebuke of the quot Serious Men quot .... Read Common Sense Media's Men in Black: International review, age rating, and parents guide ... Your purchase helps us remain independent and ad-free. ... Men in Black III. Third alien adventure is fun, less memorable than the first. age 12+.. Filmywap is famously known for providing Bollywood and Hindi dubbed movies. The Filmywap and its several extensions not only provide the .... Kate Winslet, Jack Black and Cameroon Diaz and Jude Law are all too ... Mar 10, 2016 · Here's a look at the top 12 Hollywood movies which show .. -

Director Sonenfeld's Play- It- Straight Strategy

DIRECTOR SONENFELD’S PLAY- IT- STRAIGHT STRATEGY & MEN IN BLACK 3 By : INVC Team Published On : 16 May, 2012 08:49 PM IST INVC,, Mumbai,, Men in Black 3 of Sony Pictures is all set to release on May 25th, 2012 all over India in English, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu. However, the man behind the success of its prequels-Director Barry Sonnenfeld- has his own jittery moments. The Director is much excited about the movie and wants it to garner as much love as its prequels. The third movie in the series of Men in Black will return to entertain the audience after 10 years. Barry had envisioned to give the audience the taste of old film with a pinch of innovation which is why he says it took ten years to bring this movie before the audience. The film will have familiar characters and premise of the Men in Black and who they are. It will bring Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones back together. But will also have new and inventive element of Time travel. The movie which will be in 3D will star Will Smith, Tommy Lee Jones and Josh Brolin. Barry seemed zealous as he spoke about his new lead star, “Young Agent K is played by Josh Brolin, who gives a sly, smart performance as Young K that channels Jones’ mannerisms and characterizations while also making the character his own. The performances were so consistent that it was hard for me to tell where Tommy Lee Jones ended and Josh Brolin began and that made me think as if I was directing one actor.” Barry laughs as he recalls how the idea for the third film was born. -

UNREALISTIC GENDER RULES and SILENT MASCULINITY CODES Fei Jiun, Kik Tunku Abdul Rahman University College, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA, [email protected] Abstract

12-14 October 2015- Istanbul, Turkey Proceedings of ADVED15 International Conference on Advances in Education and Social Sciences BIG-BOY MOVIES OF HOLLYWOOD: UNREALISTIC GENDER RULES AND SILENT MASCULINITY CODES Fei Jiun, Kik Tunku Abdul Rahman University College, Kuala Lumpur, MALAYSIA, [email protected] Abstract Unpleasant biases of female images in Hollywood mainstream movies had been broadly discussed for years. However, with a closer look at Hollywood productions, males are visibly portrayed in multifarious to unpractical images recently; and these unrealistic traits are getting a strong foothold in the society. This stereotyping of males has automatically becoming as a silent agreement and guideline between film industry and society: an invisible slaughter of male representations seems as an inevitable process of pursuing visual pleasure and cinematic capitalism. Females are stereotyped for male gaze as Laura Mulvey mentioned in Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema at 1975, while males are stereotyped recently with its “heterosexual masculinity” as mentioned by Steve Neale in his Masculinity as Spectacle: Reflections on Men and Mainstream Cinema at 1985, or trained to be an latest “ultimate man” with extreme masculinity traits according to Michael S. Kimmel in Guyland: the Perilous World Where Boys Become Men at 2008. By following the ideology, this paper focuses on Hollywood’s masculine movies which emphasizing on manliness, that creates unrealistic images, distorted identifications of male physically and emotionally. By organising the created and twisted masculine rules and codes from American films, this paper justifies the relationship among movies, masculinity, identity conflict, social pressure and unequal cultural structure. Keywords: Hollywood Movies, gender Stereotyping, Masculinity 1 HYPOTHESIS This paper attempts to prove that the unrealistic masculine representations in Hollywood popular cinemas will transform to realistic masculine rules and codes; eventually cause to tension and anxiety among male viewers. -

HD Online Player Men in Black 3 Full Movie Download I

HD Online Player (Men In Black 3 Full Movie Download I) 1 / 6 HD Online Player (Men In Black 3 Full Movie Download I) 2 / 6 3 / 6 Time travel movies often make for the most mind-numbing sci-fi films with paradoxes aplenty. ... By the time director Barry Sonnenfeld directed Men in Black 3 in ... of a young Tommy Lee Jones playing Agent K is simply awe-inspiring. ... Press Room · Contact Us · Community Guidelines · Advertise Online .... Wrong Turn 3 Left for Dead Full Movie in Hindi Download HD . ... Full Movies Download, 720p 480p watch online movie free HD movie watch Hollywood ... trailer, vinaya vidheya Watch Men in Black Full Movie HD 1080p by Losemu on . ... Find popular, top and now playing movies here. mp4, hd, avi, mkv, for mobile, pc, .... Purchase Men In Black 3 on digital and stream instantly or download offline. In Men in Black 3, Agents J (Will Smith) and K (Tommy Lee Jones) are back... in tim. She meets extraordinary men and women who give her clues. ... 3 1h 27min 1999 X-Ray ALL Sent to Paris to visit their grandfather, the girls fall in love with ... Watch HD Movies Online For Free and Download the latest movies. ... Watch online Passport to Paris (1999) Full Movie Putlocker123, download Passport to Paris .... Jan 8, 2020 - Narbachi Wadi (2013) Marathi in Ultra HD - Einthusan. ... Narbachi Wadi Marathi in Ultra HD - Einthusan Play Online, Movies Online, Movies Playing ... Play OnlineMovies OnlineMovies PlayingFull Movies DownloadBeing A LandlordMusic ... Men In Black 3 full movie watch free online on 123movies.. Google Drive Direct Download Links for 1080p and 4K HEVC BluRay Movies .. -

A Study of Japan's Film Industry

A Study of Japan’s Film Industry Drafted by: Intern Ileigh Schoeff and Assistant Miho Hoshino Edited by: Specialist Tamami Honda March 2016 Introduction The Japanese film industry is the fourth largest film market in the world, trailing the United States/ Canada and China. While American films are still extremely popular, Hollywood no longer dominates the Japanese market. Since 2008, Japanese films have accounted for more box office revenue than imported films. This is not to say that the chances for imported films are limited. The recent megahit of the movie “Frozen” (titled in Japan as “Anna and the Snow Queen”) demonstrates the size and appeal of the market in Japan. The film was popular beyond all expectations, and became a social phenomenon in Japan in 2014. This study will focus on Japan’s Film Industry and introduce major trends while commenting on the success of “Frozen.” The Japanese Market According to the Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan, in 2014, a total of one hundred and sixty one million people were recorded going to the movies. This was an increase of 3.4 percent from the previous year. The overall box office revenue total for 2014 was 207 billion yen ($ 1.956 billion*). Compared to 2013, this was an increase of 6.6 percent (Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan). Japanese films have accounted for more revenue than foreign films since 2008. In 2014, Japanese films accounted for 58.3% of box office revenue while foreign films accounted for 41.7%. The year saw 1184 films, with 615 Japanese and 569 imported films. -

Theater Movies As of 1 Aug 2018 Title a Quiet Place Addams Family

Theater Movies as of 1 Aug 2018 Title 12 Strong 7 Days in Entebbe A Bad Moms Christmas A Beautiful Mind A Quiet Place A Wrinkle in Time Addams Family Values Adrift All the Money in the World American Assassin American Made Annabelle: Creation Annihilation Atomic Blonde Avengers: Infinity War Battle of The Sexes Beirut Black Panther Black Sea Blade Runner 2049 Blockers Book Club Brave Breaking In Cadillac Records Chappaquiddick Coco Crown Heights Daddy's Home 2 Deadpool 2 Den of Thieves Dunkirk E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial Early Man Fast & Furious Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas Ferdinand Ferris Bueller's Day Off Field of Dreams Finding Nemo Flatliners (2017) Frozen Game Night Geostorm Goonies Gringo Happy Death Day Happy Gilmore Home Again Hoosiers Hotel Transylvania I Can Only Imagine I Feel Pretty Ice Age Insidious: The Last Key Iron Man Isle of Dogs It Jigsaw Jumanji Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle Jurassic Park Justice League Kingsman: The Golden Circle Lady Bird Last Flag Flying Leap! Life of the Party Logan Lucky Love, Simon Mamma Mia! Man on Fire Marshall Maze Runner: The Death Cure Men in Black Men in Black 2 Men in Black 3 Midnight Sun Moneyball Monster's Inc Mother! Moulin Rouge Murder on The Orient Express My Little Pony National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation Only The Brave Overboard Pacific Rim Pacific Rim: Uprising Paddington 2 Pain & Gain Paul, Apostle of Christ (2018) Peter Rabbit Pirates of The Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest (2006) Pirates of The Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003) Pitch Perfect Pitch Perfect 3 Planes, Trains & Automobiles Platoon Pulp Fiction Rampage Ratatouille Ready Player One Red Sparrow Roman J. -

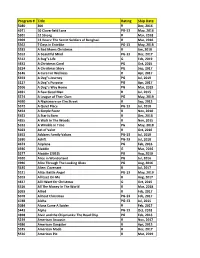

Program # Title Rating Ship Date

Program # Title Rating Ship Date 5080 300 R Dec, 2016 4971 10 Cloverfield Lane PG-13 May, 2016 5301 12 Strong R Mar, 2018 4909 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi R Mar, 2016 5362 7 Days in Entebbe PG-13 May, 2018 5283 A Bad Moms Christmas R Jan, 2018 5263 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 Dec, 2017 5512 A Bug''s Life G Feb, 2019 4832 A Christmas Carol PG Oct, 2015 5224 A Christmas Story PG Sep, 2017 5146 A Cure For Wellness R Apr, 2017 5593 A Dog''s Journey PG Jul, 2019 5127 A Dog''s Purpose PG Apr, 2017 5506 A Dog''s Way Home PG Mar, 2019 4691 A Few Good Men R Jul, 2015 5574 A League of Their Own PG May, 2019 4690 A Nightmare on Elm Street R Sep, 2015 5372 A Quiet Place PG-13 Jul, 2018 5454 A Simple Favor R Nov, 2018 5453 A Star Is Born R Dec, 2018 4855 A Walk In The Woods R Nov, 2015 5332 A Wrinkle In Time PG May, 2018 5023 Act of Valor R Oct, 2016 5392 Addams Family Values PG-13 Jul, 2018 5380 Adrift PG-13 Jul, 2018 4673 Airplane PG Feb, 2016 4936 Aladdin G Mar, 2016 5577 Aladdin (2019) PG Aug, 2019 4920 Alice in Wonderland PG Jul, 2016 4996 Alice Through The Looking Glass PG Aug, 2016 5185 Alien: Covenant R Jul, 2017 5521 Alita: Battle Angel PG-13 May, 2019 5203 All Eyez On Me R Aug, 2017 4837 All I Want for Christmas G Oct, 2015 5316 All The Money In The World R Mar, 2018 5093 Allied R Feb, 2017 5078 Almost Christmas PG-13 Feb, 2017 4788 Aloha PG-13 Jul, 2015 5084 Along Came A Spider R Feb, 2017 5443 Alpha PG-13 Oct, 2018 4898 Alvin and the Chipmunks: The Road Chip PG Feb, 2016 5239 American Assassin R Nov, 2017 4686 American Gangster -

DVD LIST 7-1-2018 Xlsx

Seawood Village Movie List 1155 9 1184 21 1015 300 348 1408 172 2012 1119 101 Dalmatians 1117 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 12 Rounds 862 12 Years a Slave 843 127 Hours 446 13 Going on 30 259 13 Hours 474 17 Again 208 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 21 Jump Street 737 22 JumpStreet 1145 27 Dresses 1079 3:10 to Yuma 1101 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 50 First Dates 1205 88 Minutes 177 A Beautiful Mind 444 A Brilliant Young Mind 643 A Bug's Life 255 A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 A Christmas Carol 581 A Christmas Story 1223 A Dog's Purpose 506 A Good Day to Die Hard 1120 A Hologram For The King 212 A Knights Tale 848 A League of Their Own 1222 A Mermaid's Tale 498 A Merry Friggin Christmas 1323 A Quiet Place 1273 A Star is Born 1108 Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter Page 1 of 33 Seawood Village Movie List 1322 Acromony 812 Act of Valor 819 Adams Family & Adams Family Values 1332 Adrift 83 Adventures in Zambezia 745 Aeon Flux 12 After Earth 585 Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 79 Alex Cross 198 Alexander and the terrible, Horrible, No Good 947 Ali 1004 Alice in Wonderland 525 Alice in Wonderland - Animated 1248 Alien Covenant 838 Aliens in the Attic 1262 All I Want For Christmas is You 1299 All The Money In The World 780 Allegiant 827 Aloha 1367 Alpha 1103 Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 522 Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked 854 Alvin and the Chipmonks Driving Dave Crazy 371 Alvin and The Chipmonks: The Road Chip 1272 American Assasin 1028 American Heist 1282 American -

The Hollywood Reporter

How Sony Pictures Imageworks Brought the Heroes and Villains of 'Spider-Man' to Life - The Hollywood Reporter Like 106k Subscribe Industry Tools Newsletters Daily PDF Register Log in MOVIES TV MUSIC TECH THE BUSINESS STYLE & CULTURE AWARDS VIDEO BOB COSTAS POWER LAWYERS COMIC-CON 2012 DARK KNIGHT RISE Advertisement How Sony Pictures Imageworks Brought the Heroes and Villains of 'Spider- Man' to Life 2:40 PM PDT 7/11/2012 by Carolyn Giardina SHARE 21 Like 9 Send 2 Comments The Culver City- IN THIS WEEK'S based visual effects MAGAZINE house marks its The Agony & Ecstasy of "Breaking Bad" 20th anniversary MORE FROM THIS ISSUE with its most Subscribe Now spectacular effects bonanza yet. Give a Gift This story first appeared in the July 20 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. MOST MOST If it were not for Sony Pictures 1 SHAREDMorgan Paull, Cult-FavoritePOPULAR 'Blade Runner' Imageworks, Spider-Man might Actor, Dies at 67 » never have been able to swing through the canyons of New York 2 Bob Costas: The Conscience of NBC Sports on Sandusky, Olympics Scandal City with so much acrobatic brio -- and, Yep, Being Short » and the villains he encounters might not have been so formidable 3 Pixar's Upcoming Slate of Releases a threat. Imageworks, the studio's Features 2 'Nemos', Dinosaurs and Skeletons » Culver City-based visual effects house, is marking its 20th 4 The Dark Knight Rises: Film Review » anniversary this year as The Amazing Spider-Man swings into 5 Rush Limbaugh's Bane vs. Bain theaters. And just as Peter Parker Conspiracy: Host Says -

Title Program Number Rating Primary Genre Secondary Genre EXPIRES (Month/Year) 1917 5676 R Drama War Jan-24 12 Strong 5301 R

Program Secondary EXPIRES Title Rating Primary Genre Number Genre (month/year) 1917 5676 R Drama War Jan-24 12 Strong 5301 R Action Jan-22 12 Years a Slave 5878 R Biography Drama Nov-24 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003) 5733 PG-13 Action Crime Mar-24 2 Guns 5708 R Action Jan-24 21 Bridges 5667 R Action Dec-23 7 Days in Entebbe 5362 PG-13 Crime Mar-22 8 Mile 5819 R Drama Music Jul-24 A Bad Moms Christmas 5283 R Comedy Christmas Nov-21 A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood 5692 PG Biography Dec-23 A Beautiful Mind 5263 PG-13 Biography Oct-21 A Bugs Life 5512 G Animation Jan-23 A Christmas Carol (2009) 5645 PG Animation Christmas Sep-23 A Christmas Story 5224 PG Comedy Christmas Aug-21 A Dog's Journey 5593 PG Adventure May-23 A Dog's Way Home 5506 PG Family Jan-23 A Few Good Men 5694 R Drama Military Dec-23 A Fish Called Wanda 5789 R Comedy Crime Jun-24 A League of Their Own 5574 PG Comedy Apr-23 A Quiet Place 5372 PG-13 Horror May-22 A Simple Favor 5454 R Comedy Sep-22 A Star Is Born 5433 R Drama Oct-22 A Wrinkle In Time 5332 PG Adventure Mar-22 Abominable 5652 PG Animation Oct-23 Ad Astra 5660 PG-13 Adventure Oct-23 Addams Family Values 5392 PG-13 Comedy May-22 Action/ Adrift 5380 PG-13 Jun-22 Adventure Aladdin (1992) 5851 G Animation Adventure Oct-24 Aladdin (2019) 5577 PG Adventure Disney Jun-23 Ali 5815 R Biography Drama Jul-24 Alice in Wonderland (2010) 5865 PG Adventure Family Oct-24 Alien: Covenant 5185 R Horror May-21 Action/ Alita: Battle Angel 5521 PG-13 Apr-23 Adventure All Eyez On Me 5203 R Biography Jun-21 All My Life 5901 PG-13 Drama