Edward Hayes, Liverpool Colonial Pioneer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of Establishments 2020/21- Index

CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE’S SERVICE DIRECTORY OF ESTABLISHMENTS 2020/21- INDEX Page No Primary Schools 2-35 Nursery School 36 Secondary Schools 37-41 Special Schools 42 Pupil Referral Service 43 Outdoor Education Centres 43 Adult Learning Service 44 Produced by: Children and Young People’s Service, County Hall, Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL7 8AE Contact for Amendments or additional copies: – Marion Sadler tel: 01609 532234 e-mail: [email protected] For up to date information please visit the Gov.UK Get information about Schools page at https://get-information-schools.service.gov.uk/ 1 PRIMARY SCHOOLS Status Telephone County Council Ward School name and address Headteacher DfE No NC= nursery Email District Council area class Admiral Long Church of England Primary Mrs Elizabeth T: 01423 770185 3228 VC Lower Nidderdale & School, Burnt Yates, Harrogate, North Bedford E:admin@bishopthorntoncofe. Bishop Monkton Yorkshire, HG3 3EJ n-yorks.sch.uk Previously Bishop Thornton C of E Primary Harrogate Collaboration with Birstwith CE Primary School Ainderby Steeple Church of England Primary Mrs Fiona Sharp T: 01609 773519 3000 Academy Swale School, Station Lane, Morton On Swale, E: [email protected] Northallerton, North Yorkshire, Hambleton DL7 9QR Airy Hill Primary School, Waterstead Lane, Mrs Catherine T: 01947 602688 2190 Academy Whitby/Streonshalh Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 1PZ Mattewman E: [email protected] Scarborough NC Aiskew, Leeming Bar Church of England Mrs Bethany T: 01677 422403 3001 VC Swale Primary School, 2 Leeming Lane, Leeming Bar, Stanley E: admin@aiskewleemingbar. Northallerton, North Yorkshire, DL7 9AU n-yorks.sch.uk Hambleton Alanbrooke Community Primary School, Mrs Pippa Todd T: 01845 577474 2150 CS Sowerby Alanbrooke Barracks, Topcliffe, Thirsk, North E: admin@alanbrooke. -

Surnames in Bureau of Catholic Indian

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Montana (MT): Boxes 13-19 (4,928 entries from 11 of 11 schools) New Mexico (NM): Boxes 19-22 (1,603 entries from 6 of 8 schools) North Dakota (ND): Boxes 22-23 (521 entries from 4 of 4 schools) Oklahoma (OK): Boxes 23-26 (3,061 entries from 19 of 20 schools) Oregon (OR): Box 26 (90 entries from 2 of - schools) South Dakota (SD): Boxes 26-29 (2,917 entries from Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records 4 of 4 schools) Series 2-1 School Records Washington (WA): Boxes 30-31 (1,251 entries from 5 of - schools) SURNAME MASTER INDEX Wisconsin (WI): Boxes 31-37 (2,365 entries from 8 Over 25,000 surname entries from the BCIM series 2-1 school of 8 schools) attendance records in 15 states, 1890s-1970s Wyoming (WY): Boxes 37-38 (361 entries from 1 of Last updated April 1, 2015 1 school) INTRODUCTION|A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|Q|R|S|T|U| Tribes/ Ethnic Groups V|W|X|Y|Z Library of Congress subject headings supplemented by terms from Ethnologue (an online global language database) plus “Unidentified” and “Non-Native.” INTRODUCTION This alphabetized list of surnames includes all Achomawi (5 entries); used for = Pitt River; related spelling vartiations, the tribes/ethnicities noted, the states broad term also used = California where the schools were located, and box numbers of the Acoma (16 entries); related broad term also used = original records. Each entry provides a distinct surname Pueblo variation with one associated tribe/ethnicity, state, and box Apache (464 entries) number, which is repeated as needed for surname Arapaho (281 entries); used for = Arapahoe combinations with multiple spelling variations, ethnic Arikara (18 entries) associations and/or box numbers. -

Rag Parades, Halls & David Bowie

Development Alumni Relations & Events. Rag Parades, Halls & David Bowie. Experiences of University life 1965–84 The winning Stephenson Hall float, Rag 1969. Photo from John Bitton (BEng Civil and Structural Engineering 1970) Twikker, 1969. Photo Archive, University of Sheffield Accommodation A party in the Junior Common Room, Sorby Hall in 1964. Steve Betney (BSc Physics 1965) Thank you This magazine is the result of a request for memories of student life from alumni of The University of Sheffield who graduated in the years 1965 to 1984. The publication provides a glimpse into an interesting period in the University’s history with the rapid expansion of the campus and halls of residence. The eyewitness accounts of the range and quality of bands promoted by the Students’ Union are wonderful testimony to the importance of Sheffield as a city of music. And the activities of students during the Rag Parade and Boat Race would create panic in the Health and Safety Executive if repeated today. I wish to thank everyone who responded so generously with their time and sent us their recollections and photos. Just a fraction of the material appears here; all of the responses will become part of the University Archives. Miles Stevenson The residents of Crewe Hall (popularly known as Kroo’All in those Director of Alumni and Donor days) were a notorious bunch of students whose cruel initiations Relations of their new members were very original. In my case, during Crewe Hall Autumn 2015 that initiation night three senior members brought me up by lift to the top floor of the nearby Halifax Hall. -

International Student Handbook 2018-19 Entry

Uxbridge College International Student Handbook 2018-19 Entry www.uxbridgecollege.ac.uk Contents Page Welcome to Uxbridge College 3 Immigration – Applying for Your Visa 4 Packing for Your Departure 6 Getting to the UK 7 Arriving in the UK 8 Pre-Arrival Checklist 10 Getting to College 11 Money 12 Accommodation in the UK 13 Accommodation near Uxbridge College 15 Biometric Residence Permit Collection 20 Police Registration 21 Safety 22 Weather/Climate 25 Daylight Saving Time 26 Settling In 27 Contacting Home 28 Opening Times 30 Food Stores 31 Religion 35 Getting to know Uxbridge & Hayes 37 Clubs & Activities 38 Enrolment & Induction 41 Bank Accounts in the UK 42 Transferring Money 44 Healthcare during your stay 45 Council Tax 48 Essential Documents Checklist 49 Studying at Uxbridge College 50 Facilities 54 Support at Uxbridge College 55 Work 59 Extending Your Visa 59 HCUC - A MERGER BETWEEN UXBRIDGE COLLEGE AND HARROW COLLEGE On 1 August 2017 Uxbridge College and Harrow College merged to become HCUC. The colleges are now officially part of the same organisation and will work together to provide the best opportunities for our students. We are part of the same organisation but the colleges will keep their individual names. We will still be known as Uxbridge College and our students will study on one of our two campuses in Uxbridge and Hayes. 2 Uxbridge College London International Student Handbook 2018-19 Entry WELCOME TO UXBRIDGE COLLEGE LONDON We are delighted that you have chosen to come and study at Uxbridge College, and hope that your stay with us will be an enjoyable and fulfilling one. -

Yorkshire Archaeological Research Framework: Research Agenda

Yorkshire Archaeological Research Framework: research agenda A report prepared for the Yorkshire Archaeological Research Framework Forum and for English Heritage – project number 2936 RFRA S. Roskams and M. Whyman (Department of Archaeology, University of York) Date: May, 2007 ABSTRACT This report represents the outcome of research undertaken into the extent, character and accessibility of archaeological resources of Yorkshire. It puts forward a series of proposals which would allow us to develop their use as a research and curatorial tool in the region. These involve systematically testing the evidence for patterning in the data, augmenting the present database, and establishing the research priorities for the Palaeolithic to the Early Modern period. Acknowledgements: to be completed YARFF members as a whole plus, at least,: Helen Gomersall (WYAS) Graham Lee (NYM) Robert White (Dales) Peter Cardwell Pete Wilson Marcus Jeacock Margaret Faull David Cranstone James Symonds, Rod MacKenzie and Hugh Wilmott Mike Gill Jan Harding Martin Roe Graham Hague Relevant YAT staff Aleks McClain Regional curatorial staff 2 CONTENTS Summary 4 Introduction 7 Section 1. Testing, Accessing and Augmenting Yorkshire’s Databases 10 1.1 Testing the Resource Assessment database 1.2 The relationship between the Resource Assessment database and Yorkshire HERs 1.3 Museum holdings 1.4 Enhancing the quality of recent commercial data holdings 1.5 Remote sensing evidence 1.6 Waterlogged and coastal evidence 1.7 Industrial archaeology 1.8 Standing buildings 1.9 Documentary sources 1.10 Human resources Section 2. Period Priorities 20 2.1 The Palaeolithic period 2.2 The Mesolithic period 2.3 The Neolithic period 2.4 The Bronze Age 2.5 The Iron Age 2.6 The Romano-British Period 2.7 The Early Medieval Period 2.8 The High Medieval Period 2.9 The Early Modern period/Industrial Archaeology Bibliography 39 3 SUMMARY This report draws together the implications of the papers presented by Manby et al. -

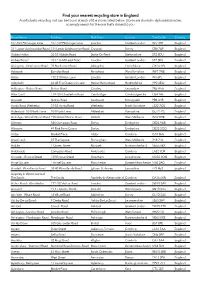

Find Your Nearest Recycling Store in England a Soft Plastic Recycling Unit Can Be Found at Each of the Stores Listed Below

Find your nearest recycling store in England A soft plastic recycling unit can be found at each of the stores listed below. Stores are shared in alphabetical order, so simply search for the one that’s closest to you. Store Name Address Post Town County Post Code Country 107-109 Pitshanger Lane 107-109 Pitshanger Lane London Greater London W5 1RH England 311 Lower Addiscombe Road 311 Lower Addiscombe Road Croydon Surrey CR0 7AF England Abbey Hulton 53-55 Abbots Road Stoke-On-Trent Staffordshire ST2 8DU England Abbey Wood 103-116 McLeod Road London Greater London SE2 0BS England Abingdon - Northcourt Road 39 Northcourt Road Abingdon Oxfordshire OX14 1PJ England Ackworth Barnsley Road Pontefract West Yorkshire WF7 7NB England Acton 192-210 Horn Lane London Greater London W3 6PL England Adeyfield 46-48 The Queens Square Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire HP2 4EW England Adlington - Bolton Road Bolton Road Chorley Lancashire PR6 9NA England Ailsa Court 179-185 Chesterton Road Cambridge Cambridgeshire CB4 1AF England Ainsdale Station Road Southport Merseyside PR8 3HR England Ainsty Road Wetherby 51-55 Ainsty Road Wetherby North Yorkshire LS22 7QS England Aldershot - 264 North Lane 264 North Lane Aldershot Hampshire GU12 4TJ England Aldridge - Walsall Wood Road 198 Walsall Wood Road Walsall West Midlands WS9 8HB England Allenton 840 Osmaston Road Derby Derbyshire DE24 9AB England Allestree 49 Park Farm Centre Derby Derbyshire DE22 2QQ England Alston Market Place Alston Cumbria CA9 3HS England Alvechurch 25 The Square Birmingham West Midlands B48 7LA England Amble 1 Queen Street Morpeth Northumberland NE65 0BX England Ambleside Compston Road Ambleside Cumbria LA22 9DR England Ancaster - Ermine Street 139 Ermine Street Grantham Lincolnshire NG32 3QN England Angel Square 1 Angel Square Manchester Greater Manchester M60 0AG England Ansdell - Woodlands Road 38-40 Woodlands Road Lytham St. -

A Post-Colonial Study of Museums in North Yorkshire

Exhibiting the countryside: A post-colonial study of museums in North Yorkshire Siriporn Srisinurai Master of Arts (by Research) University of York Department of Sociology October 2013 1 Abstract This dissertation attempts to understand the images and stories of the countryside exhibited in two local museums in North Yorkshire – the Ryedale Folk Museum, Hutton le Hole and the Beck Isle Museum of Rural Life, Pickering. The study was conducted through qualitative methods mainly based on multi-sited museography, documentary and visual archives, and interviews. Using a postcolonial framework, this research’s findings relate to three main arguments. First, museums and modernity: the research explores both museums as theatres of memory rather than as a consequence of the heritage industry. The emergence of these museums involves practices that responded to industrialisation and modernity, which led to massive and rapid changes in the Ryedale countryside and nearby rural ways of life. Second, museums and the marginal: “the countryside” exhibited in both museums can be seen as the margins negotiating with English nationalism and its dominant narratives of homogeneity, unity and irresistible progress. Three key aspects involved with this process are space, time, and people. The first part of the research findings considers how both museums negotiated with English nationalism and the use of the countryside as a national narrative through images of the countryside “idyll” and the north-south divide. The second part illustrates how local folk museums exhibited “folklife” as the “chronotopes of everyday life” in contrast with the “typologies of folk objects”. The third part focuses on forgotten histories and domestic remembering of space, time and people based on the “local and marginal” rather than the “universal and national”. -

The London Gazette, Hth July 1986

9270 THE LONDON GAZETTE, HTH JULY 1986 of Matter—22 of 1981. Date Fixed for Hearing—17th Devonshire, and before that of and carrying on business September 1986. Hour—2 p.m. Place—County Court as before as Tony Hayes Cameras from 5 Wentworth Office, Belgrave House, Bank Street, Sheffield SI 1EH. Way, Bletchley, aforesaid. Court—NORTHAMPTON. No. of Matter—27 of 1986. Trustee's Name, Address ORDERS FOR AUTOMATIC DISCHARGE and Description—Miller, Martin Jonathan, 69 Windsor Road, Prestwich, Manchester, Accountant. Date of Cer- BIGGS, Alan Britt of no present occupation of and lately tificate of Appointment—30th June 1986. trading as a Self-emoloyed Bricklayer at 19 Romero Square, Ferrier Estate, Kidbrooke, London S.E.3, lately HASSAN, Mehmet, of 75 Mayors Road, Altrincham in residing at 16 World End Estate, Ashbourne Tower, the county of Cheshire, trading under the style of Atatt London S.E.10, described in the Receiving Order as A. International as a HAULAGE CONTRACTOR, form- Biggs (male) of and lately residing and carrying on erly residing at and trading from 111 Windsor Road, business at 10 Romero Sauare, Ferrier Estate, Kidbrooke, Prestwich, Manchester, in the county of Greater Man- London, SE3, Builder." Court—HIGH COURT OF chester. Court—SALFORD. No. of Matter—16 of 1985. JUSTICE. No. of Matter—647 of 1981. Date of Order Trustee's Name, Address and Description—Lee, John —13th October 1981. Date of Adjudication Order— Hendrik Chadwick of Messrs. Horsfield & Smith, 8 18th June 1981. Date of operation of Order of Discharge Manchester Road, Bury, Lancashire, Chartered Account- —18th June 1986. -

Housing Market Areas and Functional Economic Market Areas in Buckinghamshire and the Surrounding Areas

Housing Market Areas and Functional Economic Market Areas in Buckinghamshire and the surrounding areas Volume II: Study Appendices March 2015 Opinion Research Services | The Strand • Swansea • SA1 1AF | 01792 535300 | www.ors.org.uk | [email protected] Opinion Research Services ▪ Atkins | Identifying HMAs and FEMAs in Buckinghamshire and the surrounding areas Volume II: Study Appendices Opinion Research Services | The Strand, Swansea SA1 1AF Jonathan Lee | David Harrison | Tara McNeill enquiries: 01792 535300 · [email protected] · www.ors.org.uk Atkins | Euston Tower, 286 Euston Road NW1 3AT Richard Ainsley enquiries: 020 7121 2280 · [email protected] · www.atkinsglobal.com © Copyright March 2015 Opinion Research Services ▪ Atkins | Identifying HMAs and FEMAs in Buckinghamshire and the surrounding areas Volume II: Study Appendices Contents Appendix A: Analysis of Valuation Office Data Appendix B: Sectoral Strengths Appendix C: LA-LA Commuting and Migration Flows Appendix D: Stakeholder Engagement Appendix E: Study Method Statement Appendix F: Responses to Study Method Statement Appendix G: Workshop Presentation of Emerging Findings Appendix H: Further Information Circulated following Workshop Appendix I: Responses to the Emerging Findings Appendix J: Responses to the Report of Findings Consultation Draft Appendix K: Schedule of Changes to the Final Report of Findings Opinion Research Services ▪ Atkins | Identifying HMAs and FEMAs in Buckinghamshire and the surrounding areas Volume II: Study Appendices Appendix A Analysis of -

Graham, Yitka, Hayes, Catherine, Mahawar, Kamal, Small, Peter

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sunderland University Institutional Repository Graham, Yitka, Hayes, Catherine, Mahawar, Kamal, Small, Peter, Attala, Anita, Seymour, Keith, Woodcock, Sean and Ling, Jonathan (2017) Ascertaining the place of social media and technology for bariatric patient support: what do allied health practitioners think? Obesity Surgery. ISSN 0960-8923 (Print) 1708-0428 (Online) Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/6881/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Title: Ascertaining the place of social media and technology for bariatric patient support: what do allied health practitioners think? Type of Manuscript: Type 1, original contribution Authors: Yitka N H Graham1, 2, PhD, BSc (Hons), Senior Lecturer in Public Health and Researcher in Bariatric Surgery Email: [email protected] Catherine Hayes,1 PhD, MA, Principal Lecturer in Health Email: [email protected] Kamal K Mahawar 1,2, MS, MSc, FRCSEd, Consultant General Surgeon with Bariatric Interest Email: [email protected] Peter K Small,1,2, RD, MD, FRCSEd, Consultant General Surgeon with Bariatric Interest Email: [email protected] Anita Attala3, BSc, RD, CertEd, Specialist Dietitian for Bariatrics and Diabetes Email: [email protected] Keith Seymour,3, MD, FRCS, Consultant General Surgeon with Bariatric Interest Email: [email protected] -

Heathland Restoration at Keston and Hayes Commons Part of Darwin's

Heathland Restoration at Keston and Hayes Commons Part of Darwin’s Landscape Laboratory Dr. Judith John & Jennifer Price Abstract The heathland, acid grassland and lowland valley mire of Hayes and Keston Commons (Northwest Kent) have long been popular places for Londoners on a day out, and for naturalists and scientists to visit, including Charles Darwin who studied round-leaved sundew in Keston Bog and earthworms on the heathland. This paper describes the history of the commons and reasons for the decline in habitat quality and species diversity since the mid 20th century. Actions taken to halt and reverse habitat degradation and species loss include clearance of secondary woodland and scrub, soil scraping, re-seeding of heather, bracken removal, building dams across the valley mire and cutting and clearing purple moor-grass from Keston bog. Detailed field surveys have been key in guiding and monitoring the success of management decisions. Raising awareness of the importance of heathland habitat has been very successful in reconciling concerns of the local community and enlisting the support of many volunteers whose work has been vital for this long- term project. The area of heathland, lowland valley mire and fen habitat has now increased, the area covered by some uncommon plant species has expanded and other species have reappeared. Much remains to be done, however, and maintenance of the newly restored areas requires on-going work by volunteers, input from various countryside agencies and involvement of the local authority whose support is crucial but a cause of concern should their funding continue to be reduced. Introduction Hayes and Keston Commons are situated near Bromley on the southern edge of the Thames Basin in vice county 16, 12 miles (I9.3 km) from central London and but within the M25. -

Your Graduation

Your Graduation. Summer 2021 1 The University of Sheffield Your Graduation: Summer 2021 Contents The University Sheffield 3 Welcome from the President and Vice-Chancellor 4 Reasons to be proud 5 Conferment of Degrees: Faculty of Arts and Humanities 9 Faculty of Engineering 15 Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health 25 Faculty of Science 28 Faculty of Social Sciences 36 Prizes and Awards 48 Sheffield Alumni 62 Officers of The University of Sheffield 63 2 The University of Sheffield Your Graduation: Summer 2021 The University of Sheffield Your graduation day is a special day for you and your family, a day for celebrating your achievements and looking forward to a bright future. As a graduate of the University of Sheffield you have every reason to be proud. You are joining a long tradition of excellence stretching back more than 100 years. The University of Sheffield was founded with the amalgamation of the School of Medicine, Sheffield Technical School and Firth College. In 1905, we received a Royal Charter and Firth Court was officially opened by King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. At that time, there were 363 students reading for degrees in arts, pure science, medicine and applied science. By the time of our centenary, there were over 25,000 students from more than 100 countries, across 70 academic departments. The first ever graduate of the University was its first Chancellor, the 15th Duke of Norfolk, who was awarded an Honorary Degree in 1908 prior to the first ever graduation ceremony. This graduation ceremony took place in the historic setting of Firth Hall on 2 July 1908 at 5 pm - three years after the University had been opened by King Edward VII.