Wrinkles, Wormholes, and Hamlet the Wooster Group’Shamlet As a Challenge to Periodicity Amy Cook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ticket Info ::: Directions 2021-22 Season

Please Note Evening Show shoW TiMEs ::: TicKET info ::: DirEcTIonS p.m. 7:30 Change To Time 2021-22 sEason Single Ticket Prices: Seating Chart Adults........................................................... $15 Seniors.(62 and over)................................ $14 5 13 Students.(18 and under).......................... $14 1 4 Stage 14 17 Left Center Right Gift.Certificates.. (Good for one Admission) ........................$15 1 4 5 13 14 17 To purchase tickets, please visit our website: auroraplayers.org. To purchase tickets over 1 16 the phone, you may leave a message at Riser 687-6727 and a volunteer will call you back as soon as possible. 1 21 Show Times: Order Tickets/Contact Us: Please Note Evening Show Time Change auroraplayers.org 716.687.6727 Friday, Saturday ......................... 7:30 p.m. Aurora Players, Inc. Sunday Matinée ............................. 2:30 p.m. P.O. Box 206, East Aurora, NY 14052 Historic Roycroft Pavilion Located at the NORTH GROVE STREET Home of Aurora Players, Inc. Welcome to theNORTH WILLOW STREET Historic Roycroft Pavilion: PARKDALE AVENUE RIDGE AVENUE CHURCH STREET northern end of RILEY STREET SHEARER AVENUE WHALEY AVENUE TO/FROM BOWEN ROAD PINE STREET Hamlin Park on SENECA STREET (RT. 16) MAPLE ROAD TO/FROM RT South Grove Street, W. FIL L MORE AVENUE FILL MORE AVENUE EAST FILL MORE AVENUE the historic Roycroft . 400 Middle Pavilion is home to School Aurora Players and M AIN STREET (RT. 20A) M AIN STREET (RT. 20A) PAINE STREET RT. 400 EXPRESSWAY PARK PL ACE SOUTH GROVE STREET OLEAN STREET (RT. 16) its productions. Roycroft Campus WALNUT STREET A picturesque CENTER STREET SOUTH WILLOW STREET Roycroft Inn ELM STREET OAKWOOD 30-minute drive ) A 0 2 . -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT SWR2 Musikstunde Blumen und Pflastersteine 1968 und die musikalische Verjüngung der Welt (3) Mit Michael Struck-Schloen Sendung: 11. April 2018 Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2018 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Musikstunde können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde mit Michael Struck-Schloen 09. April – 13. April 2018 Blumen und Pflastersteine 1968 und die musikalische Verjüngung der Welt 3. Ideologische Zuspitzung und Gewaltausbruch Und heute wieder: „Blumen und Pflastersteine ‒ 1968 und die musikalische Verjüngung der Welt“. Herzlich willkommen sagt Michael Struck-Schloen. Und ich will heute da weitermachen, wo die gestrige Sendung endete ‒ bei den Blumenkindern und Hippies, die ihr Zentrum in San Francisco hatten, aber bald auch in Paris oder auf dem Berliner Ku’damm zu sehen waren. Eine Zwischenstation war New York, wo im April 1968 das Musical Hair am Broadway herauskam und zu einem der erfolgreichsten Musicals aller Zeiten wurde ‒ obwohl Aussteiger und Kriegsdienstverweigerer mit langen Haaren, Hass aufs Establishment und Lust auf Drogen und Sex die Hauptrollen spielten. Aber letztlich war gerade diese Mischung auch das Erfolgsrezept. -

Creating the Role of Crissy in Hair

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Capstone Projects 2021 Creating the Role of Crissy in Hair Yu Miao Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Acting Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Miao, Y (2021). Creating the role of Crissy in Hair [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/1120/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. CREATING THE ROLE OF CRISSY IN HAIR by YU MIAO A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN THEATRE ARTS MINNESOTA STATE UNIVERSITY, MANKATO MANKATO, MINNESOTA MARCH 2021 Date 04/07/21 Creating the role of Crissy in Hair Yu Miao This thesis has been examined and approved by the following members of the student’s committee. ________________________________ Dr. Heather Hamilton ________________________________ Prof. Matthew Caron ________________________________ Prof. David McCarl ________________________________ Dr. Danielle Haque i ABSTRACT Miao, Yu, M.F.A. -

Law, Justice, and All That Jazz: an Analysis of Law's Reach Into Musical Theater

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2015 Law, Justice, and All that Jazz: An Analysis of Law's Reach into Musical Theater Amy Oldenquist University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Oldenquist, Amy, "Law, Justice, and All that Jazz: An Analysis of Law's Reach into Musical Theater" (2015). Master's Theses and Capstones. 914. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/914 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAW, JUSTICE, AND ALL THAT JAZZ: AN ANALYSIS OF LAW’S REACH INTO MUSICAL THEATER BY AMY L. OLDENQUIST BA Psychology & Justice Studies, University of New Hampshire, 2014 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Justice Studies September, 2015 This thesis has been examined and approved. Thesis Co-Chair, Katherine R. Abbott, Lecturer in Sociology and Justice Studies Thesis Co-Chair, Ellen S. Cohn, Professor of Psychology and Coordinator of the Justice Studies Program John R. Berst, Assistant Professor of Theater and Dance (musical theater) September, 2015 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family, my mother Jean and my brother Billy who have stood by me and encouraged me to keep going through thick and thin. -

A New Dawn for Hair by Richard Zoglin

Back to Article Click to Print Thursday, Jul. 31, 2008 A New Dawn for Hair By Richard Zoglin I never saw the original production of Hair, but I did catch the show a couple of years after its 1968 Broadway debut, when the touring company came to San Francisco. I was a student at Berkeley, and I would occasionally take a break from dodging tear gas in Sproul Plaza to usher for plays in the city. It was a good deal: students could spend half an hour helping fat cats find their way to their orchestra seats and, after the curtain went up, take any empty seat for free. Except that the night I saw Hair, the house was full, so the ushers had to sit on the aisle steps in the balcony. Which turned out to be the perfect way to experience the celebrated "tribal rock musical" that brought the communal spirit of the '60s youth culture to Broadway for the first time. It was the greatest night of my theater life. Well, maybe not quite. But allow a baby boomer his memories. (To be honest, I probably didn't call them fat cats either.) And allow Hair--or so even some professed fans of the show have pleaded--to remain in the mists of '60s nostalgia. After a flop 1977 Broadway revival and a not-much-more-successful 1979 movie version directed by Milos Forman, the feeling seemed to harden that the Age of Aquarius was over and trying to bring it back would look hopelessly out of touch, even silly, in this cynical new millennium. -

Creation of the Tribe HAIR: the American Love- Rock Musical By

Creation of the Tribe HAIR: The American Love- Rock Musical By Adalia Vera Tonneyck B.F.A in Fibers, August 2008, Savannah College of Art and Design A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences Of The George Washington University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Masters of Fine Art May 20, 2012 Thesis directed by Sigridur Johnannesdottir Associate Professor of Theatre Table of Contents List of Figures [Renderings] iii List of Figures [Production Photos] iv Chapter 1: [Introduction] 1-2 Chapter2: [The Vietnam War] 3-7 Chapter 3: [The Hippie Culture of America] 8-11 Chapter 4: [HAIR an American Love-Rock Musical] 12- 16 Chapter 5: [The Director´s Vision] 17-19 Chapter 6: [THE HAIR IN HAIR] 20-25 Chapter 7: [Bring the Vision to Life Through Costumes] 26-47 Chapter 8: [Conclusion] 48 Figures [Renderings] 49-62 Figures [Production Photos] 63-75 References 76-96 Documents [Pieces list] 97-100 Bibliography 101-102 ii Renderings Figure 1 [Berger] 50 Figure 2 [Claude] 51 Figure 3 [Hud] 52 Figure 4 [Sheila] 53 Figure 5 [JEAINE] 54 Figure 6 [Woof] 55 Figure 7 [Crissy] 56 Figure 8 [The Tribe] 57 Figure 9 [The Tribe] 58 Figure 10 [Margaret Mead] 59 Figure 11 [Hubert] 60 Figure 12[The Supremes] 61 Figure 13 [White Girl Trio] 62 iii Production Photos Figure 1 [Woof] 64 Figure 2 [Hud] 65 Figure 3 [The Supremes] 66 Figure 4 [Margaret Mead] 67 Figure 5[White Girl trio] 68 Figure 6[Dream] 69 Figure 7[Claude] 70 Figure 8[Berger] 71 Figure 9[Sheila] 72 Figure 10[Tribe] 73 Figure 11[Berger, Claude and Sheila] 74 Figure 12[Claude is died] 75 iv Chapter 1: Introduction All my fellow production design graduate students and myself were given our thesis assignments April 2011 at the end of GWU academic year. -

Radical Joy Project

THE A theatrical performance project Radical that confronts our past, breathes into our present moment, and Joy Project envisions our future A full company Freeing the Creative Spirit collaboration Co-directors: Jarvis Green Rebecca Martínez Carol Dunne Kevin Smith, music director Production design collaborators: Laurie Churba, Michael Ganio, Dan Kotlowitz Students of THEA 41, stage management A three-part project: The Past Thu, Apr 8, 8 pm ET The Present & Future Fri, Apr 9, 8 pm ET On the Hopkins Center Hop@Home YouTube Channel https://dartgo.org/joy Post-performance discussion, Fri, Apr 9 CAST Alex Bramsen '22 Isaiah Brown '23 Kate Budney '21 Jacqui Byrne '22 Ellie Hackett '23 Lila Hovey '23 Min Hur '24 Madeline Levangie ''21 Dawn Lim '24 Edward Lu '21 Chara Lyons '23 Melissa MacDonald GR Jelinda Metelus '22 Riley Schofner '24 Isabel Wallace '21 Lexi Warden '21 Isabella Yu '23 STAGE MANAGEMENT TEAM Lucy Biberman '23 Isaiah Brown '23 Sara Cavrel '23 Melyanet Espinal '24 Thomas Latta '18 Matt Law '23 Dawn Lim '24 Elle Muller '24 Nat Stornelli '21 Nitin Venkatdas '23 Tori Dozier Wilson '20 Part I Carol Dunne, director Christian Williams '19, video editor Anthony Robles '20, assistant video editor Sam West '20, sound design A Keen for a Newspaper ......................................Melissa MacDonald GR soundscape Kean Haunt film design Melissa McDonald GR Unprecedented Shit .............................Isaiah Brown '23, Jacqui Byrne '22, Ellie Hackett '23, Edward Lu '21 music and lyrics Ani DiFranco music production Jamie Hackett guitar Seth Eliser We Conclude 2020 ..............Alex Bramsen '22, Isaiah Brown '23, Min Hur '23, Edward Lu '21, Jelinda Metelus '22, Lexi Warden '21 written by Alex Bramsen '22 Hongyeon 홍연 ............................................................ -

American Music Review the H

American Music Review The H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XLIII, Number 2 Spring 2014 Busted for Her Beauty: Hair’s Female Characters1 Elizabeth Wollman, Baruch College and CUNY Graduate Center When it opened on Broadway at the Biltmore Theatre on 29 April 1968, Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical was hailed by critics and historians as paradigm shifting. While a few critics dismissed the musical as loud, chaotic and confusing, most wrote glowingly of its energy, its ability to harness the commercial potential of the theatrical mainstream to the experimentalism taking place off Broadway, and its disarmingly affectionate depiction of a frequently misunderstood or maligned subculture. Perhaps more importantly, Hair was heralded for managing to do what had been deemed impossible: it brought rock music to Broadway in a way that didn’t offend young audiences and didn’t alienate older ones. “This is a happy show musically,” Clive Barnes enthused in The New York Times. “[Hair] is the first Broadway musical in some time to have the authentic voice of today rather than the day before yesterday.”2 Reception histories about Hair remain over- whelmingly focused on the show’s many inno- vations,3 which I have no intention of debating here; I believe Hair deserves its landmark status. Nevertheless, it has long bothered me that this musical, like the era it came from, tends to be remembered so romantically and uncritically. One aspect of Hair that I find particularly unsettling is a case in point: despite its left-leaning approach to the many social and political issues it tackles, Hair is jarringly old- fashioned in its depictions of women, which no previous scholarship on the musical has exam- ined in depth. -

Suggested Reading List

UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE AT CHATTANOOGA DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE & SPEECH SUGGESTED READING LIST PLAYS GREEK DRAMA • THE ORESTEIA Aeschylus • MEDEA Euripides • OEDIPUS THE KING Sophocles • ANTIGONE Sophocles • LYSISTRATA Aristophanes • THE MENAECHMI Plautus • THE BROTHERS Terence MEDIEVAL DRAMA • THE SECOND SHEPHERD’S PLAY Anonymous (Wakefield Cycle) • EVERYMAN Anonymous • DULCITIUS Hrosvitha ITALIAN RENAISSANCE • LA MANDRAGOLA (a. k. a. THE MANDRAKE) Niccolò Machiavelli ENGLISH RENAISSANCE • VOLPONE Ben Jonson • THE SPANISH TRAGEDY Thomas Kyd • DOCTOR FAUSTUS Christopher Marlowe • KING LEAR William Shakespeare • HAMLET William Shakespeare • MACBETH William Shakespeare • OTHELLO William Shakespeare • AS YOU LIKE IT William Shakespeare • A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM William Shakespeare • TWELFTH NIGHT William Shakespeare • THE TAMING OF THE SHREW William Shakespeare • JULIUS CAESAR William Shakespeare • HENRY IV PART ONE William Shakespeare • RICHARD III William Shakespeare • HENRY V William Shakespeare • THE DUCHESS OF MALFI John Webster FRENCH RENAISSANCE • TARTUFFE Molière • THE MISANTHROPE Molière • PHÈDRE Jean Racine SPANISH GOLDEN AGE • LIFE IS A DREAM Pedro Calderón de la Barca ENGLISH RESTORATION & 18th CENTURY • THE ROVER Aphra Behn • THE BUSY BODY Suzanna Centlivre • SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER Oliver Goldsmith • SCHOOL FOR SCANDAL Richard Sheridan • THE COUNTRY WIFE William Wycherly GERMAN, FRENCH AND ITALIAN 18TH CENTURY • THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO Pierre Beaumarchais • FAUST PART I Johann Wolfgang Goethe • THE SERVANT OF TWO MASTERS Carlo -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

“KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. The other members of my dissertation committee, Dr. David Crespy and Dr. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

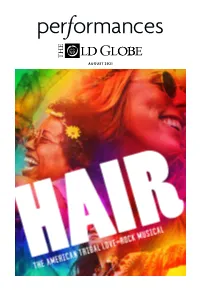

AUGUST 2021 WELCOME BACK Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of Hair. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do, and supporting us through our extended intermission. Now more than ever, as we return to live performances, our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatri- cal experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations.