Ways of Solving Problems Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letsgopeay.Com /Letsgopeay @Letsgopeay @Letsgopeay Noting the Game Vs

COLBY WILSON BASKETBALL CONTACT E: [email protected] P: 615-604-3803 GOVERNORS BASKETBALL | 13-TIME OHIO VALLEY CONFERENCE CHAMPION | 2018 OVC FRESHMAN OF THE YEAR 2018-19 GAME NOTES | THE UT MARTIN REMATCH AUSTIN PEAY (20-8, 12-3) vs UT MARTIN (10-16, 5-10) SCHEDULE Feb. 23, 2019 ■ DUNN CENTER ■ CLARKSVILLE, TENN. DATE OPPONENT TIME THE MATCHUP FASTBREAK Nov. 6 Oakland City W, 114-53 • One last home contest awaits the Govs in the 2018- Nov. 9 at No. 18 Mississippi State L, 67-95 19 campaign, as Austin Peay finishes the Dunn Jersey Mike’s Jamaica Classic (Varied Sites) Center slate by hosting UT Martin, Saturday. Nov. 12 at South Florida L, 70-74 (OT) • This contest will be the last chance for the Austin Peay Nov. 16 vs. Central Connecticut W, 80-78 faithful to honor a quintet of seniors--Jarrett Givens, Nov. 18 vs. Campbell L, 72-78 Zach Glotta, Steve Harris, Jabari McGhee and Chris Nov. 24 at Ohio L, 82-85 (OT) Porter-Bunton--for their contributions to the program. Nov. 29 at Troy W, 79-74 (OT) AUSTIN UT • Three Governors--Jabari McGhee, Terry Taylor, Chris Dec. 1 at Alabama A&M W, 73-61 PEAY MARTIN Porter-Bunton--rank among the top-15 in the OVC in Dec. 8 Calvary W, 116-33 fi eld goal percentage, tied for most in the league. Dec. 15 Purdue Fort Wayne W, 95-68 2018-19 RECORD 2018-19 RECORD 20-8 ■ 12-3 OVC 10-16 ■ 5-10 OVC Only Quintin Dove (fi fth, 59.4 percent) represents St. -

ORIGINAL ATLANTA DIVISION FILED )NC~FR}('$( U ~ ~.R`

Case 1:00-cv-01716-CC Document 125 Filed 02/24/03 Page 1 of 296 f IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OE GEORGIA ORIGINAL ATLANTA DIVISION FILED )NC~FR}('$( U ~ ~.r`. q~i,ti DARRON EASTERLING, 1003 Plaintiff, Civil Action dpi e~. ; ;1R S v . 1 :00-CV-171E L WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP WRESTLING, JURY TRIAL DEMANDED INC ., TURNER SPORTS, INC . and TURNER BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC . Defendants . PLAINTIF'F'S NOTICE OF FILING APPENDIX Plaintiff, DARRON EASTERLING, hereby serves notice that he is filing herewith in the above-styled case an Appendix containing copies oz relevant deposition testimony and exhibit documents in support of his Response To Defendants' Motion For Summary Judgment filed with this Cou This Z4 day of --I'~7~(jWn ~~ 3 . / Yi' Ca'ry chter Georg~ Bar No . 382515 Charle J . Gernazian Georgia Bar No . 291703 Michelle M . Rothenberg-Williams Georgia Bar No . 615680 MEADOWS, ICHTER 6 BOWERS, P .C . Fourteen Piedmont Center, Suite 1100 3535 Piedmont Road Atlanta, GA 30305 Telephone : (909) 261-6020 Telecopy : (404) 261-3656 Case 1:00-cv-01716-CC Document 125 Filed 02/24/03 Page 2 of 296 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE This is to certify that I have this day served all parties in the foregoing matter with the foregoing Plaintiff's Notice of Filing Appendix by depositing a copy of same in the United States Mail, postage prepaid and properly addressed as follows : Eric Richardson Evan Pontz Troutman Sanders LLP Suite 5200, Bank of America Plaza 600 Peachtree Street, N .E . Atlanta, Georgia 30308-22165 This 2~~ day of Februak~, coos . -

I 1 I G 1St Runner up Quail Valley’S Nose Knows

185th - Bi-Monthly - June/July 2015 WWW.NSTRA.ORG I 1 I G 1st Runner Up Quail Valley’s Nose Knows Adam Fellers owner/handler Mo-Kan Region 2nd Runner Up Ragin Cajun Athena Angie Fishburn, owner Wayne Fishburn, handler Indiana Region 3rd Runner Up CC’s Bayou Kate Bert Scali, owner Tytuss Rudd, handler Ohio Region JUNE/JULY 2015 I 2 I WWW.NSTRA.ORG National Shoot-To-Retrieve Field Trial Association IN THIS ISSUE June/July 2015 CONTENTS: Trial of Champions Winner ................................... Cover Trial of Champions Runner-ups ....................................2 Letter from the Officers ...............................................5 Inside this issue: National Officer Region Assignments ...........................6 Trial of Just A Reminder ..........................................................6 Champions Article: Chukar Hunting ...............................................7 p 41-59 In the Know ................................................................8 2015 Endurance Classic Entry Form .....................9 Kennel Ads ................................................................10 Butch Jackson & Cute Kids and Pup Pics .............................................12 Wayne Fishburn Official NSTRA Clothing.............................................13 smoking the meat for Wednesday’s Tips from Purina: Proper Hydration is Key..............14-15 dinner Important things to remember ..............................16-17 W.I.N. NSTRA Clothing ..............................................18 Regional Trialing ...................................................20-27 -

October 9, 1983 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena Drawing ???

October 9, 1983 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Tiger Chung Lee beat Bob Boyer. 2. Pat Patterson beat Dr. X. 3. Tony Garea beat Jerry Valiant. 4. Susan Starr & Penny Mitchell beat The Fabulous Moolah & Judy Martin. 5. Tito Santana beat Mike Sharpe. 6. Rocky Johnson beat Wild Samoan Samula. 7. Andre the Giant & Ivan Putski beat WWF Tag Champs Wild Samoans Afa & Sika. Note: This was the first WWF card in the Trotwood area. It was promoted off of their Saturday at noon show on WKEF Channel 22 which had recently replaced the syndicated Georgia Championhip Wrestling show in the same time slot. November 14, 1983 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Steve Regal beat Bob Colt. 2. Eddie Gilbert beat Jerry Valiant. 3. Tiger Chung Lee beat Bob Bradley. 4. Sgt. Slaughter beat Steve Pardee. 5. Jimmy Snuka beat Mr. Fuji. 6. Pat Patterson beat Don Muraco via DQ. 7. Bob Backlund beat Ivan Koloff. December 12, 1983 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Steve Regal drew Jerry Valiant 2. SD Jones beat Bobby Colt. 3. Tony Atlas beat Mr. Fuji via countout. 4. The Iron Sheik beat Jay Strongbow 5. The Masked Superstar beat Tony Garea. 6. WWF I-C Champion Don Muraco beat Ivan Putski via countout. 7. Jimmy Snuka beat Ivan Koloff. Last Updated: May 24, 2021 Page 1 of 16 February 1, 1984 in Trotwood, OH August 17, 1984 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Battle royal. Scheduled for the match were Andre the Giant, Tony Atlas, 1. -

Nwa Dvd Match Lists

NWA DVD MATCH LISTS NWA Disc 1 (61-77) 17. Ric Flair vs Tony Russo 1/14/1980 47 sec NWA Disc 3 (1978-1979) 18. Ric Flair vs Billy Star 2/12/1980 6:01 1. Buddy Rogers vs Pat O'Connor (3rd fall) 6/30/1961 4 mins 19. Freebirds blind JYD 3/5/1980 (Rogers wins NWA title) 1. Ric Flair vs Jumbo Tsuruta (2/3 falls) 4/27/1978 32:07 (Flair’s 20. Mulligan vs Superstar (tourney final)Flair 4/6/1980 1 min 2. Ric Flair vs Chris Taylor 12/13/1973 4 mins Japan debut) (Superstar wins NWA TV title) 3. Ric Flair/Rip Hawk interview 1974 2. Flair/Superstar vs Steamboat/Jones 1978 (House Show) 5 mins 21. Masked Superstar Interview 4/6/1980 4. Jack Brisco vs Shohei Baba (2/3 falls) 12/2/1974 24:46 (Baba 3. Ric Flair vs Blackjack Mulligan (Cage) 1978 (House Show) 4 22. Ric Flair vs Jimmy Sunka 4/20/1980 2 mins (Flair wins US title) wins NWA title) mins 23. Snuka/Sheik/Gene Anderson interview 4/27/1980 5. Harley Race vs Dory Funk Jr 5/24/1973 1 min (Harley Race wins 4. Ric Flair vs BJ Mulligan 1978 (House Show) 7 mins 24. Rhodes/Ole vs Assassins cage(Ole turns) 7/1/1980 3 mins NWA title) 5. Ric Flair vs BJ Mulligan (Texas Death) 1978 (House Show) 8 25. Flair/Valentine vs Sheik/Snuka 7/8/1980 7 mins 6. Dusty Rhodes vs The Shiek 1975 2 mins mins 26. -

Wrestling Observer Newsletter February 24, 1992

Wrestling Observer Newsletter February 24, 1992 A few weeks ago I started hearing speculation about the significant lost revenue from those avenues. A potential sprint possible demise of Hulk Hogan and even the potential demise race by sponsors in the wrong direction and domino effect of of Titan Sports. While in a worst-case scenario of what could television stations which would cause a lessening of exposure happen, one couldn't completely rule that out as a possibility. would indirectly lead to a major effect on live attendance and all But it was maybe a 200-to-one longshot, at best. Most of this other revenue sources. At the same time, a promoter like Don talk was incredibly premature and so unlikely at the time that it King, who in comparison makes Vince McMahon seem like a didn't seem to be worth serious discussion. saint, has survived and prospered even though most Americans have an idea of what kind of a person he really is. People will It's still premature. It's still unlikely. But it's also worth serious pay money to see an entertainment/sport even if the owner has discussion. Make no mistake about it. Friday night, if it were not a shady rep forever because they are paying to see the for some incredible luck, the Titan empire may have been in a performers. But boxing isn't marketed as a kids show and aired race to avoid crumbling before Wrestlemania. Even with the in syndication primarily on Saturday mornings, so parts of that incredible luck, it may be too late for Titan to inevitably avoid analogy doesn't hold up. -

Wrestling Observer Newsletter February 17, 1992

Wrestling Observer Newsletter February 17, 1992 Just days after the Florida state legislature voted down the bill licensed with the commission so that their names would be on to implement steroid testing of pro wrestlers, World file for the random anabolic steroid and street drug tests, Championship Wrestling Executive Vice President Kip Frey however there would be no licensing or registration fee announced the promotion would be announcing an anti-steroid policy within the next week. No details about the policy were *Promoters would be charged an annual fee for a promoter's available at press time but it will include wrestlers making public license. If the promoter averaged more than 1,000 paying service anti-steroid promos on television. Hopefully Frey, who is spectators per event in Florida over the previous year, his a newcomer to the wrestling world, will realize the touchiness license fee would be $1,000 (which would mean only WWF and involved in this issue and not try to have wrestlers who have WCW). All others wishing to promote would have to pay $250 achieved the spotlight partially through the use of steroids for a promoters license (which covers a lot of ground) to then make statements that give one the impression they would never touch the stuff. Frey *There would be a five percent tax on all live gates. The original also said in comments for this coming Sunday's Miami Herald bill included taxes not only on live gates, but also on gimmicks that WCW would be instituting a policy to post signs in front of sold at live events and pay-per-view revenue from systems arenas when advertised talent isn't going to appear. -

Cogjm Criterion 1966-02-17.Pdf (2.234Mb)

C\\\~JllE i ON Of MESA M COLLf:Gf Vol. No. XXXIII Thursday, February 17, 1966 No. 8 Local Pubs Report Losses From Theft, Vanda1ism by Karla Porter It's Friday afternoon. No one is in 300 people went to a party and two away. the study lounge or library. Even the of them got in a fight, the only thi ng The guilty party quipped, "I made social lounge and snack bar are de you would hear about would be the the Criterion last week! I'm the loud serted. Where is everybody? FAC. fight-298 people had a great time, mouth at the basketball game." I Friday Afternoon Club) but . you would only hear about the Another patron confessed, " I stole Th e scene shifts to the Shad where two that got in a fight." a pitcher and two glasses." But he was one chapter of this national organiza The Pina Hut, run by Duane Moore, holding up three fingers. tion congregates to release tension was loosing from five to six dozen Ted Kubena of Shakey's said that accumulated is spent dancing, laugh glasses a week and has lost 12 dozen he might not loose a thing for three ing and enjoyi ng themselves, they ashtrays since the first of November. weeks and the following week he would leave-occassionally with a souvin er of A rough estimate of his loss for the loose two dozen mugs and a dozen the day's fun. past 14 weeks is a bout $190 ' to $225. glasses. The mugs cost 40c and the Dave Perry, known as Davy, to the He said there had also been a few glasses cost about 20c. -

January 4, 1982 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena

January 4, 1982 in Trotwood, OH July 16, 1982 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Jimmy Garvin beat The Angel. 1. Match results unavailable. 2. Brad Armstrong drew Buzz Sawyer. 3. Bob Armstrong beat Ron Bass. 4. Tommy Rich beat The Masked Superstar. 5. Terry Gordy & The Super Destroyer beat Mr. Wrestling II & Michael Hayes when Gordy pinned Hayes. July 30, 1982 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Andre the Giant vs. Harley Race. January 21, 1982 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Brad Armstrong beat Ricky Harris. August 13, 1982 in Trotwood, OH 2. Buzz Sawyer beat Jim Garvin. Hara Arena drawing ??? 3. Dusty Rhodes beat The Great Kabuki. 4. The Masked Superstar & The Super Destroyer DDQ Bob Armstrong & Terry 1. Tito Santana beat Terry Gibbs. Taylor. 2. Roddy Piper beat Brad Armstrong. 5. Tommy Rich beat NWA World Champ Ric Flair via DQ. 3. Paul Orndorff beat Don Muraco via DQ. 4. Tommy Rich & Dusty Rhodes beat Ole Anderson & Stan Hansen via DQ. 5. Andre the Giant beat The Masked Superstar. 6. Andre the Giant won a “battle royal.” February 21, 1982 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Tom Pritchard beat Angel. September 14, 1982 in Trotwood, OH 2. Terry Taylor beat Rick Harris. Hara Arena drawing ??? 3. The Masked Superstar & The Super Destroyer beat Mr. Wrestling II & Brad Armstrong. 1. Tom Pritchard beat Chick Donovan. 4. Andre the Giant DCO Harley Race. 2. Tito Santana & Johnny Rich beat The Iron Sheik & Matt Borne. 5. Tommy Rich beat The Great Kabuki via DQ. -

Other Promotions

Memphis Wrestling Last Updated: May 10, 2021 Page 1 of 15 June 12, 1980 in Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Gardens drawing ??? 1. Robert Gibson beat Ken Wayne. 2. Carl Fergie beat The International Superstar. 3. Bill Dundee & Ricky Morton beat Wayne Ferris & Larry Latham. 4. Jimmy Valiant & Ken Lucas beat Skull Murphy & Gypsy Joe. 5. Sonny King beat Southern Champ Paul Ellering. September 18, 1980 in Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Gardens drawing ??? 1. Ken Wyane vs. Carl Fergie. 2. Tommy & Eddie Gilbert vs. Karl Krupp & El Mongol. 3. Southern Champ Jimmy Valiant vs. Bill Irwin. 4. Bill Dundee vs. Tommy Rich. 5. CWA World Champ Billy Robinson vs. Sonny King. Last Updated: May 10, 2021 Page 2 of 15 Mid-Atlantic Wrestling Last Updated: May 10, 2021 Page 3 of 15 January 31, 1981 in Cincinnati, OH June 27, 1981 in Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Gardens drawing ??? Cincinnati Gardens drawing ??? 1. Jackie Ruffin beat Jim Nelson via DQ. 1. Bill White beat Mike Miller. 2. The Iron Sheik beat Frankie Laine. 2. Terry Latham beat Charlie Fulton. 3. Ivan Koloff & Jimmy Snuka beat George Wells & Johnny Weaver. 3. Leroy Brown & Sweet Ebony Diamaond beat Jimmy Valiant & Greg 4. Blackjack Mulligan beat Bobby Duncum. Valentine. 5. Ric Flair beat Greg Valentine. 4. The Masked Superstar beat The Iron Sheik via DQ. 5. NWA Tag Champs Ole & Gene Anderson beat Paul Jones & Jay Youngblood. February 21, 1981 in Cincinnati, OH Cincinnati Gardens drawing ??? July 25, 1981 in Cincinnati, OH 1. Frankie Laine drew Ron Ritchie. Cincinnati Gardens drawing ??? 2. John Ruffin beat Abe Jacobs. 3. -

Shawn Michaels

Shawn Michaels Michael Shawn Hickenbottom (born July 22, 1965), better known by his ring name Shawn Michaels, is an American professional wrestling personality, television presenter and retired professional wrestler. Currently signed to WWE, as an ambassador and trainer, since December 2010. Michaels wrestled consistently for WWE, formerly the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), from 1988 until his first retirement in 1998. He held non- wrestling roles from 1998 to 2000 and resumed wrestling in 2002 until retiring ceremoniously in 2010. In the WWF/E, Michaels headlined major pay-per-view events between 1989 and 2010, closing the company's flagship annual event, WrestleMania, five times. He was the co-founder and original leader of the successful stable, D-Generation X. He also wrestled in the American Wrestling Association (AWA), where he founded The Midnight Rockers with Marty Jannetty in 1985. After winning the AWA Tag Team Championship twice, the team continued to the WWF as The Rockers, and had a high-profile breakup in January 1992. Within the year, Michaels would twice challenge for the WWF World Heavyweight Championship and win his first WWF Intercontinental Championship, heralding his arrival as one of the industry's premier singles stars. He won the Pro Wrestling Illustrated "Match of the Year" reader vote a record eleven times. Widely considered as one of the greatest professional wrestlers of all time, Michaels is a four-time world champion, having held the WWF World Heavyweight Championship three times and WWE's World Heavyweight Championship once. He is also a two-time Royal Rumble winner, the first WWF Grand Slam Champion and the fourth WWF Triple Crown Champion, as well as a 2011 WWE Hall of Fame inductee. -

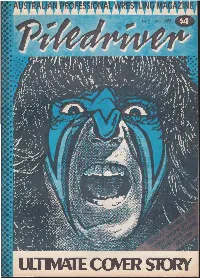

Ultimt\TE C<MR

ULTIMt\TE C<MR r---MELBOURNE PILEDRIVER OUTLETS SYDNEY---. Minotaur Books • Science Fiction • Fantasy ATERFRONT • Movie • TV • Rock • Videos • Games • Posters • Novelties RECORDS 770 George Street 128 Elizabeth St, Sydney Melbourne (ent. Barlow St.) (Comics: 288 Flinders Lane) ~Y,EAITtE ~ NE'WvA<.1~NCY Shop 2 Au-Go-Go Records 39 Darcy Roed WENTWORTHVILLE 3Lt9 L ITfLE BURt<E. ST. N.S.W. 2146 Melbourne Phone: 670 0677 S'fONEY Collector's Item Piledriver No. 1 "fl'e -~ .....----BRISBANE that started it all - small in size FOOTBALL BOOKS! comfortably in a pocket or handba£ ·: FOOTBALL RECORDS! ROCKING HORSE It's football books (new & 2nd hd). football everywhere with you!) but large O" - records (AFL, VFA, interstate), football cards (cigarette, Scanlans) . ation . 1 Invaluable glossary 1 MELBOURNE SPORTS BOOKS Brody tribute 1 WWF cham Football material bought and sold 158 Adelaide St Art1cl es by Dr D and Leapm' La Ring me: House calls made, cash paid. BRISBANE Best range of fdotba/1 in Melb! SS eac c. postage a c " d 1st FLOOR, 238 FLINDERS LANE , MELB. Ph 229 5360 Phone: (03) 650 9782 Fax 221 1702 ~i\Qdri'f€r ~q.'3 • Art1c1es Aussie writers! Limited copies e inc. postage and handling . e Send cheque or money order WRESTLING $5 for each copy Line Please make payable)j::.."df ~-iJ-f ., PO Box 34, Glenhuntly, Vic .. ::: ~u~@j .. AUSTRALIA 3163 .: :m~ C' ~~~~~ ---------...:;; ; :.:~- Send me ... .. .. copies of No. I enclose $ ............. to cover all a mcludmg postage and handling Overseas Orders: $6 per copy incl. airmail freight. Name ij From Around The World..