Eth-50419-01.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia: Background and U.S

Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy Updated September 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45307 SUMMARY R45307 Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy September 5, 2018 Georgia is one of the United States’ closest non-NATO partners among the post-Soviet states. With a history of strong economic aid and security cooperation, the United States Cory Welt has deepened its strategic partnership with Georgia since Russia’s 2008 invasion of Analyst in European Affairs Georgia and 2014 invasion of Ukraine. U.S. policy expressly supports Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders, and Georgia is a leading recipient of U.S. aid in Europe and Eurasia. Many observers consider Georgia to be one of the most democratic states in the post-Soviet region, even as the country faces ongoing governance challenges. The center-left Georgian Dream party has more than a three-fourths supermajority in parliament, allowing it to rule with only limited checks and balances. Although Georgia faces high rates of poverty and underemployment, its economy in 2017 appeared to enter a period of stronger growth than the previous four years. The Georgian Dream won elections in 2012 amid growing dissatisfaction with the former ruling party, Georgia: Basic Facts Mikheil Saakashvili’s center-right United National Population: 3.73 million (2018 est.) Movement, which came to power as a result of Comparative Area: slightly larger than West Virginia Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution. In August 2008, Capital: Tbilisi Russia went to war with Georgia to prevent Ethnic Composition: 87% Georgian, 6% Azerbaijani, 5% Saakashvili’s government from reestablishing control Armenian (2014 census) over Georgia’s regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Religion: 83% Georgian Orthodox, 11% Muslim, 3% Armenian which broke away from Georgia in the early 1990s to Apostolic (2014 census) become informal Russian protectorates. -

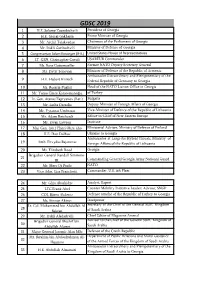

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

Who Owned Georgia Eng.Pdf

By Paul Rimple This book is about the businessmen and the companies who own significant shares in broadcasting, telecommunications, advertisement, oil import and distribution, pharmaceutical, privatisation and mining sectors. Furthermore, It describes the relationship and connections between the businessmen and companies with the government. Included is the information about the connections of these businessmen and companies with the government. The book encompases the time period between 2003-2012. At the time of the writing of the book significant changes have taken place with regards to property rights in Georgia. As a result of 2012 Parliamentary elections the ruling party has lost the majority resulting in significant changes in the business ownership structure in Georgia. Those changes are included in the last chapter of this book. The project has been initiated by Transparency International Georgia. The author of the book is journalist Paul Rimple. He has been assisted by analyst Giorgi Chanturia from Transparency International Georgia. Online version of this book is available on this address: http://www.transparency.ge/ Published with the financial support of Open Society Georgia Foundation The views expressed in the report to not necessarily coincide with those of the Open Society Georgia Foundation, therefore the organisation is not responsible for the report’s content. WHO OWNED GEORGIA 2003-2012 By Paul Rimple 1 Contents INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................3 -

Unanswered Questions and Replies by Others in Parliament

Image not found or type unknown UNANSWERED QUESTIONS AND REPLIES BY OTHERS IN PARLIAMENT According to the Constitution of Georgia and the Rules of Procedure of the Parliament, an MP is entitled to submit a written question to any state institution. The questions shall be posted on the parliament's website and a relevant note added in case of a delayed reply or no reply. However, the above appears to be insufficient to fully implement the mechanism of parliamentary control. The tool is most frequently utilized by members of parliament. However, the number of questions is low if they are related to the defense and security sector. In total, from 6 December 2018 to 1 August 2019, lawmakers asked the government 175 questions. Of these, 12 questions were addressed to the Minister of Internal Affairs, 3 to the Special Penitentiary Service, and 1-1 question to Head of the State Security Service of Georgia and Special State Protection Service, respectively. No questions were asked by lawmakers to the Head of the Intelligence Service and the Head of Operational- Technical Agency. In addition, it is important that the answer be accompanied by a signature of the addressee, but practice shows that in most cases this is not the case. Of 175 questions asked to ministers during the reporting period, only 52 were answered. The legislation emphasizes the obligation to provide a timely and comprehensive answer to any queries that MPs might have. However, if the provisions are breached, it does not result in sanctions. This may also be due to the fact that the legislative measures are of an extreme nature (e.g. -

![Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There Are](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0963/survey-on-political-attitudes-april-2019-1-show-card-1-there-are-800963.webp)

Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There Are

Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There are different opinions regarding the direction in which Georgia is going. Using this card, please, rate your answer. [Interviewer: Only one answer.] Georgia is definitely going in the wrong direction 1 Georgia is mainly going in the wrong direction 2 Georgia is not changing at all 3 Georgia is going mainly in the right direction 4 Georgia is definitely going in the right direction 5 (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 2. [SHOW CARD 2] Using this card, please tell me, how would you rate the performance of the current government? Very badly 1 Badly 2 Well 3 Very well 4 (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 Performance of Institutions and Leaders 3. [SHOW CARD 3] How would you rate the performance of…? [Read out] Well Badly answer) Average Very well Very (Refuse to (Refuse Very badly Very (Don’t know) (Don’t 1 Prime Minister Mamuka 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Bakhtadze 2 President Salome 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Zourabichvili 3 The Speaker of the Parliament 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Irakli Kobakhidze 4 Mayor of Tbilisi Kakha 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Kaladze (Tbilisi only) 5 Your Sakrebulo 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 6 The Parliament 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 7 The Courts 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 8 Georgian army 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 9 Georgian police 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 10 Office of the Ombudsman 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 11 Office of the Chief Prosecutor 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 12 Public Service Halls 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 13 Georgian Orthodox Church 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 4. -

Parliament of Georgia in 2019

Assessment of the Performance of the Parliament of Georgia in 2019 TBILISI, 2020 Head of Research: Lika Sajaia Lead researcher: Tamar Tatanashvili Researcher: Gigi Chikhladze George Topouria We would like to thank the interns of Transparency International of Georgia for participating in the research: Marita Gorgoladze, Guri Baliashvili, Giorgi Shukvani, Mariam Modebadze. The report was prepared with the financial assistance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Norway Contents Research Methodology __________________________________________________ 8 Chapter 1. Main Findings _________________________________________________ 9 Chapter 2. General Information about the Parliament ____________________ 12 Chapter 3. General Statistics ____________________________________________ 14 Chapter 4. Important events ______________________________________________ 16 4.1 Interparliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy (chaired by Russian Duma Deputy Gavrilov) and a wave of protests _________________________________ 16 4.2 Failure of the proportional election system __________________________ 17 4.3 Election of Supreme Court judges ____________________________________ 19 4.4 Abolishing Nikanor Melia’s immunity and terminating his parliamentary mandate ________________________________________________________________ 20 4.5 Changes in the Composition of Parliamentary Subjects _______________ 20 4.6 Vote of Confidence in the Government _____________________________ 21 4.7 Report of the President ______________________________________________ 21 Chapter -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA January 27-29 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: January 30, 2020 Occupied Regions Abkhazia Region 1. Aslan Bzhania to run in so-called presidential elections in occupied Abkhazia Aslan Bzhania, Leader of the occupied Abkhazia region of Georgia will participate in the so-called elections of Abkhazia. Bzhania said that the situation required unification in a team that he would lead. So-called presidential elections in occupied Abkhazia are scheduled for March 22. Former de-facto President of Abkhazia Raul Khajimba quit post amid the ongoing protest rallies. The opposition demanded his resignation. The Cassation Collegiums of Judges declared results of the September 8, 2019, presidential elections as null and void (1TV, January 28, 2020). Foreign Affairs 2. EU Special Representative Klaar Concludes Georgia Visit Toivo Klaar, the European Union Special Representative for the South Caucasus and the crisis in Georgia, who visited Tbilisi on January 20-25, held bilateral consultations with Georgian leaders. Spokesperson to the EU Special Representative Klaar told Civil.ge that this visit aimed to discuss the current situation in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali Region/South Ossetia, as well as ―continuing security and humanitarian challenges on the ground,‖ in particular in the context of the Tskhinvali crossing points, which ―remain closed and security concerns are still significant.‖ Several issues discussed during the last round of the Geneva International Discussions (GID), which was held in December 2019, were also raised during his meetings. ―This visit allows him to get a better understanding of the Georgian position as well as to pass key messages to his interlocutors,‖ Toivo Klaar‘s Spokesperson told Civil.ge earlier last week (Civil.ge, January 27, 2020). -

Tion Media Monitoring

Election Media Monitoring July 17-30, 2012 Key findings identified during the media monitoring for the period of July 17-30: According to the time allocated by Rustavi 2 and Imedi, the sequence of the first top five subjects and time distribution coincide to one another. These are: the President, the Government, the Coalition Georgian Dream, Christian-Democratic Movement and New Rights. Likewise, the time distribution is similar on Maestro and the Ninth Channel. Here the following sequence is present: Coalition Georgian Dream, the government, United National Movement, the President and local NGOs. According to the time allocated by the First Channel, Kavkasia and Real TV, the Coalition Georgian Dream ranks first. However, there are big differences from the standpoint of time distribution. Distribution of the time allocated to the subjects on the first channel is the most equal of all, and the least equal on Real TV. On the First Channel, all the subjects, except the government, have a more than 50% share of direct speech. Distribution of direct and indirect speech on Rustavi 2 and Imedi is similar, like it is the case of distribution of allocated time. In both cases the Coalition Georgian Dream has the lowest share of direct speech out of those subjects to which more than 5 minutes were allocated. The Coalition Georgian Dream has very similar distribution of direct and indirect speech on Maestro, Kavkasia and the Ninth Channel – almost half of the allocated time. The government has a very little share of direct speech on the Ninth Channel. Such indicator has not been observed on any other channel among those subjects to which more than 4 minutes were allocated. -

Unanswered Questions and Replies by Others in Parliament

Image not found or type unknown UNANSWERED QUESTIONS AND REPLIES BY OTHERS IN PARLIAMENT According to the Constitution of Georgia and the Rules of Procedure of the Parliament, an MP is entitled to submit a written question to any state institution. The questions shall be posted on the parliament's website and a relevant note added in case of a delayed reply or no reply. However, the above appears to be insufficient to fully implement the mechanism of parliamentary control. The tool is most frequently utilized by members of parliament. However, the number of questions is low if they are related to the defense and security sector. In total, from 6 December 2018 to 1 August 2019, lawmakers asked the government 175 questions. Of these, 12 questions were addressed to the Minister of Internal Affairs, 3 to the Special Penitentiary Service, and 1-1 question to Head of the State Security Service of Georgia and Special State Protection Service, respectively. No questions were asked by lawmakers to the Head of the Intelligence Service and the Head of Operational- Technical Agency. In addition, it is important that the answer be accompanied by a signature of the addressee, but practice shows that in most cases this is not the case. Of 175 questions asked to ministers during the reporting period, only 52 were answered. The legislation emphasizes the obligation to provide a timely and comprehensive answer to any queries that MPs might have. However, if the provisions are breached, it does not result in sanctions. This may also be due to the fact that the legislative measures are of an extreme nature (e.g. -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 91, 7 February 2017 2

No. 91 7 February 2017 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html ARMENIAN PROTESTS AND POLITICS Special Editor: Alina Poghosyan, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences of Armenia ■■The Electric Yerevan between Reproduction and Change 2 Arpy Manusyan, Yerevan ■■A Self-Repeating Crisis: the Systemic Dysfunctionality of Armenian Politics 5 Armen Ghazaryan, Yerevan ■■Civic Processes in Armenia: Stances, Boundaries and the Change Potential 8 Sona Manusyan, Yerevan ■■BOOK REVIEW Anna Zhamakochyan, Zhanna Andreasyan, Sona Manusyan, and Arpy Manusyan (2016): Փոփոխության Որոնումներ (Quest for Change) 11 Reviewed by Armine Ishkanian, London Paturyan, Yevgenya Jenny and Gevorgyan, Valentina (2016): Civic Activism as a Novel Component of Armenian Civil Society 13 Reviewed by Karena Avedissian, Los Angeles, CA ■■CHRONICLE 8 December 2016 – 6 February 2017 15 This special issue is funded by the Academic Swiss Caucasus Network (ASCN). Research Centre Center Caucasus Research German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies Resource Centers East European Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 91, 7 February 2017 2 The Electric Yerevan between Reproduction and Change Arpy Manusyan, Yerevan Abstract In reaction to the decision of the government of Armenia to raise the electricity tariff by 16.9 percent, sev- eral hundred young people gathered in Freedom Square and protested against this robbery on June 18, 2015. In the early morning of June 23, the police used water cannons to brutally disperse the demonstrators and arrested 237 of them. These events [unexpectedly] brought thousands of citizens to Baghramyan Avenue, which remained closed for approximately two weeks. -

Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy

Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy Cory Welt Specialist in European Affairs Updated April 1, 2019 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R45307 SUMMARY R45307 Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy April 1, 2019 Georgia is one of the United States’ closest partners among the states that gained their independence after the USSR collapsed in 1991. With a history of strong economic aid Cory Welt and security cooperation, the United States has deepened its strategic partnership with Specialist in European Georgia since Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia and 2014 invasion of Ukraine. U.S. Affairs policy expressly supports Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its [email protected] internationally recognized borders, and Georgia is a leading recipient of U.S. aid to For a copy of the full report, Europe and Eurasia. please call 7-.... or visit www.crs.gov. Many observers consider Georgia to be one of the most democratic states in the post- Soviet region, even as the country faces ongoing governance challenges. The center-left Georgian Dream- Democratic Georgia party (GD) has close to a three-fourths supermajority in parliament and governs with limited checks and balances. Although Georgia faces high rates of poverty and underemployment, its economy in 2017 and 2018 appeared to show stronger growth than it had in the previous four years. The GD led a coalition to victory in parliamentary elections in 2012 amid growing dissatisfaction with Georgia at a Glance the former ruling party, Mikheil Saakashvili’s center- Population: 3.73 million (2018 est.) right United National Movement, which came to Comparative Area: slightly larger than West Virginia power as a result of Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution. -

Security Sector Reform in Georgia

Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development 1 SECURITY SECTOR REFORM IN GEORGIA 2004-2007 David Darchiashvili Tbilisi 2008 2 About the author: David Darchiashvili is a Professor at Ilia Chavchavadze State University. He is the author of about twenty academic publications in the fields of security studies and civil-military relations. ISBN 978-99928-37-18-4 © Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development © Ilia Chavchavadze State University 1 M. Aleksidze Str., Tbilisi 0193 Georgia Tel: 334081; Fax: 334163 www.cipdd.org 3 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Security Sector: Essence and Best Practices .................................................................................................................. 9 Strategic discourse and security problems in Georgia principles for defining sector ........................................ 17 Map of Georgian Security Sector ..................................................................................................................................27 Dilemmas of Security Sector Reform ...........................................................................................................................44 Conclusion and recommendations ................................................................................................................................63 4 Security Sector Reform in Georgia 2004-20071