The History of Gaelic Football and the Gaelic Athletic Association Jaime Orejan, Phd, Elon University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Treoir Oifigiúil Official Guide

An Treoir Oifigiúil Cuid a dó 2018-2021 Official Guide Part 2 Official Playing Rules www.facebook.com/officialcamogieassociation www.instagram.com/officialcamogie www.camogie.ie www.twitter.com/officialcamogie officialcamogie This is An Treoir Oifigiúil Cuid a Dó (Official Playing Rules 2018-2021) The other binding parts are as follows: • Part I Official Guide • Part III Code of Practice for all Officers of the Association • Part IV Disciplinary Code and THDC Mandatory Procedures • Part V Association Code on Sponsorship • Part VI Code for Camogie Supporters’ Club • Part VII Code of Behaviour (Underage) Effective from May 7th 2018 In the case of competitions at any level of the Association, that commenced prior to May 7th 2018, these competitions will be administered under the playing rules effective at the commencement of the competition. The Camogie Association Croke Park Dublin 3 Tel: 01 865 8651 Email: [email protected] Web: www.camogie.ie OFFICIAL GUIDE – Part 2 – Official Playing Rules 2018-2021 Contents 15 A-SIDE CAMOGIE ...................................................................................... 2 1. Name of the Game .................................................................................. 2 2. Team Lists ................................................................................................ 2 3. Teams’ Composition ................................................................................ 3 4. Duration of Games .................................................................................. 3 5. -

Camogie / Hurling Challenge for 5-10 Year Olds

Brídíní Óga Camogie Club – Con Magee’s GAA Club challenge Camogie / Hurling Challenge For 5-10 year olds Ground Striking: Strike/Claw Catching: Strike tennis ball on left and right off the wall, moving feet Strike the ball off the wall and try to catch it in a claw grip. constantly. Catches after a bounce count too! Claw Catching: Fundamental Movements: Throw up the ball off the wall repeatedly and catch with Try lots of different movements such as hopping, skipping and knuckles up in a claw-like grip. jumping on one or two legs. Jab/Roll Lifting: Freestyle Skills: How many jab lifts can you do in 60 seconds? How many roll Practice different unusual skills for fun - what can you do lifts can you do in 60 seconds? Try to beat your records. that your family and friends can’t? Dribbling: Jab + Strike + Control: Make a simple obstacle course to dribble through as quickly Run to the ball, jab lift it into the hand and strike off the as possible. wall. Catch or first touch it into the hand and go again. Target Practice: Solo + Target Practice: Get a bucket, tyre or similar and practice trying to hit this Make a simple obstacle course to dribble or solo through. target with the ball using both sides. Once through, strike at a target (bucket/tyre/goal etc.). Solo Running: Jab or Roll + Strike: Make a simple obstacle course to solo through as quickly as Practice free taking skills by jabbing or rolling the ball up and possible (both one- and two-handed solo runs allowed). -

Player Pathway Phases of a Camogie Player’S Development 1

Camogie Player Pathway Phases of a camogie player’s development 1 A message from the Director of Camogie Development The Camogie Player Pathway describes the opportunities to play Camogie from beginner to elite level. It is designed to give every person entering the game the chance to reach their personal potential within the sport. The pathway is divided into six stages: n Phase 1 – Get a grip 6-8 yrs approx n Phase 2 – Clash of the ash 9-11 yrs approx n Phase 3 – Get hooked 12-14 yrs approx n Phase 4 – Solo to success 15-17 yrs approx n Phase 5 – Strike for glory 17+ yrs approx n Retainment – Shifting the goalposts There are opportunities for everyone to play camogie, irrespective of age, ability, race, culture or background. The Camogie Association has adopted a logical approach to player development, so that every child and adult can reach their potential and enjoy Camogie throughout their lifetime. There are six progressive steps in a Camogie Player Pathway. Individuals will spend varying amounts of time mastering the relevant skills and attaining the requisite fitness levels. All participants should reach their potential in the stage that matches their age and aspirations. 2 For the most talented players, the player pathway ensures that they are given the very best opportunities and support to reach their full potential. Dr Istvan Baly’s Long-term Athlete Development model (LTAD) focuses on best practice in the development of players at every level. Camogie uses LTAD to develop the skills, coaches and competitions that are appropriate at each age and stage of player development. -

The Work-Rate of Substitutes in Elite Gaelic Football Match-Play

The Work-Rate of Substitutes in Elite Gaelic Football Match-Play The Work-Rate of Substitutes in Elite Gaelic Football Match-Play Eoghan Boyle 1, Joe Warne 1 2, Alan Nevill 3 Kieran Collins 1 1Gaelic Sports Research Centre, Technological University Dublin - Tallaght Campus, Dublin, Ireland,2Setanta College, Thurles, Tipperary, Ireland, and 3Faculty of Education, Health and Wellbeing, University of Wolverhampton, UK Running performance j High-intensity j Substitutes j Positional variation Headline Methodology ccording to a study assessing changes in match running During competitive match-play over two seasons, running per- Aperformance in elite Gaelic football players, there is a sig- formance was measured via a global positioning system (GPS) nificant reduction in relative high-speed distance (RHSD) in sampling at 10-Hz (VX Sport, New Zealand) in a total of 23 the second, third and fourth quarters when compared to the games. Dependent variables consisted of relative total dis- first quarter [1]. Subbed on players in elite soccer were re- tance (RTD; m·min−1), relative high-speed distance (m·−1; ported to cover greater RHSD (19.8 { 25.1 km·h−1) compared ≥17km·h−1), peak speed (km·h−1), peak metabolic power and to full game players [2]. In elite Rugby union, subbed on play- sprints per minute (accel·min−1). Relative total distance was ers generally demonstrated improved running performance in calculated as the total distance (metres) from a single match comparison to full game and subbed off players. Subbed on divided by match-play duration in minutes. Relative high- players also reported a better running performance over their speed distance was calculated as the total high-speed distance first 10 minutes of play compared to the final 10 minutes of (metres; ≥17km·h−1) from a single match divided by match- play of whom they replaced [3]. -

Gaa for All Program Cumman Lúthchleas Gael Whats Inside?

GAA FOR ALL PROGRAM CUMMAN LÚTHCHLEAS GAEL WHATS INSIDE? PAGE CONTENTS 03 What is GAA for ALL? 04 Wheelchair Hurling / Camogie 05 Football for ALL 06 Playing the Game 07 Fun and Run Game 08 Cúl Camps 09 Inclusive Club Program 10 Frequently Asked Questions 11 Contacts WHAT IS GAA FOR ALL? The first line of the GAA Official Guide spells out how the GAA reaches into every corner of Ireland and many communities around the globe. In doing this, the GAA is fully committed to the principles of inclusion and diversity at all levels Our aim: To offer an inclusive, diverse and welcoming environment for everyone. •Inclusion means people having a sense of belonging, of being comfortable in being part of something they value. Inclusion is a choice. Diversity means being aware of accommodating and celebrating difference. •Inclusion and Diversity in many ways go together. Real inclusion reflects diversity, i.e. it aims to offer that sense of belonging to everyone, irrespective of gender, marital status, family status, sexual orientation, religion, age, race or minority community and/or disability. WHEELCHAIR HURLING /CAMOGIE Playing the Game Team Composition Game commences with Throw-in Minimum age 12, no maximum age between two midfielders in centre 6 a side court All players must have physical Game split up into attacking disability half/defensive half Teams score GOALS only Pitch Layout Once a player scores they Half size regulation pitch become goalkeeper for their team Smaller than regulation goals A handpass must be followed by a Playing area -

Irish Studies Around the World – 2020

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 16, 2021, pp. 238-283 https://doi.org/10.24162/EI2021-10080 _________________________________________________________________________AEDEI IRISH STUDIES AROUND THE WORLD – 2020 Maureen O’Connor (ed.) Copyright (c) 2021 by the authors. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Introduction Maureen O’Connor ............................................................................................................... 240 Cultural Memory in Seamus Heaney’s Late Work Joanne Piavanini Charles Armstrong ................................................................................................................ 243 Fine Meshwork: Philip Roth, Edna O’Brien, and Jewish-Irish Literature Dan O’Brien George Bornstein .................................................................................................................. 247 Irish Women Writers at the Turn of the 20th Century: Alternative Histories, New Narratives Edited by Kathryn Laing and Sinéad Mooney Deirdre F. Brady ..................................................................................................................... 250 English Language Poets in University College Cork, 1970-1980 Clíona Ní Ríordáin Lucy Collins ........................................................................................................................ 253 The Theater and Films of Conor McPherson: Conspicuous Communities Eamon -

GAA | Topic Notes

GAA | Topic Notes The situation with sport Before Industrial Revolution Informal, between parishes or towns, no rules, riots common Traditional games had a bad name and were in decline Industrial Revolution Difficult to play traditional games in cities, also less time Had to have something to do with free time though Factory owners and philanthropists began to set up clubs. Led to: Set rules Organised matches Modern games began in England, spread from there (the Empire) In Ireland, these new games such as football, rugby and cricket took over Problems with the Amateur Athletics Association in Ireland Only ‘gentlemen’ could compete – ruled out the working class No Sunday games – only time working class and farmers had to play Nationalists disliked English interference The start of the GAA 1 Michael Cusack and Maurice Davin joined together after Davin saw Cusack’s article in a newspaper saying that an Irish athletics body was needed Foundation of GAA Cusack published a notice with details of the foundation meeting 7 men showed up at Hayes Hotel on the 1st November 1884 Invited Parnell, Davitt, and Archbishop Croke of Cashel to be patrons Second meeting: Rules drawn up for Gaelic football and hurling, then printed on leaflets and distributed by Davin and Cusack Rough, flawed, imprecise Only one GAA club allowed in each parish Members of GAA forbidden to compete at meeting of rival athletics associations This rule abolished by Archbishop Croke later Rapid spread – 600 clubs after 2 years, matches reported in newspapers, inter-county matches -

The Development of Grassroots Football in Regional Ireland: the Case of the Donegal League, 1971–1996

33 Conor Curran ‘It has almost been an underground movement’. The Development of Grassroots Football in Regional Ireland: the Case of the Donegal League, 1971–1996 Abstract This article assesses the development of association football at grassroots’ level in County Donegal, a peripheral county lying in the north-west of the Republic of Ire- land. Despite the foundation of the County Donegal Football Association in 1894, soccer organisers there were unable to develop a permanent competitive structure for the game until the late 20th century and the more ambitious teams were generally forced to affiliate with leagues in nearby Derry city. In discussing the reasons for this lack of a regular structure, this paper will also focus on the success of the Donegal League, founded in 1971, in providing a season long calendar of games. It also looks at soccer administrators’ rivalry with those of Gaelic football there, and the impact of the nationalist Gaelic Athletic Association’s ‘ban’ on its members taking part in what the organisation termed ‘foreign games’. In particular, the extent to which the removal of the ‘ban’ in 1971 helped to ease co-operation between organisers of Gaelic and Association football will be explored. Keywords: Association football; Gaelic football; Donegal; Ireland; Donegal League; Gaelic Athletic Association Introduction The nationalist Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), which is today the leading sporting organisation in Ireland despite its players having to adhere to its amateur ethos, has its origins in the efforts of schoolteacher and journalist Michael Cusack, who was eager to reform Irish athletics which was dominated by elitism and poorly governed in the early 1880s. -

Water Polo Balls

35 Water polo balls he South African water polo estab- and women’s balls, and for spectators and lishment is a small, intimate, brand A cut-out-and-keep feature pro- players to see the rotation of the ball. It conscious community that does not viding step-by-step information also teaches proper rotation on the ball. suffer mediocrity gladly, rarely ex- periments with inferior products on features of water polo balls. Bladder and are prepared to invest to se- Words: FANIE HEYNS. Compiled with infor- • The inner construction of the ball is equal- Tcure quality products, say local distributors. mation supplied by Nick Wiltshire, general ly important as this ultimately defines the Water polo is becoming increasingly popular manager of Pat Wiltshire Sports, local dis- ball’s pressure and shape retention prop- at school level, especially amongst girls. tributor of Mikasa balls; Nigel Prout of Opal erties. A good bladder is essential, as it Selling water polo balls to this growing, dis- Sports, local distributor of Epsan and Conti prevents the ball from becoming deflated. cerning market therefore requires a solid un- balls, Joe Schoeman of Swimming Interna- • High quality floating bladders used in derstanding of the features of the ball and the tional, distributor of Finis balls. match quality balls are made of butyl, an customer’s needs. airtight synthetic rubber, which retain their shape and correct match pressure far longer Size than latex rubber bladders. As in many other sporting codes, it is vital that • Latex (natural rubber) bladders provide water polo players use the correct size game better surface tension and flexibility that balls for their respective age groups and gen- improves bounce — which is not a benefit der. -

Camogie Development Plan 2019

Camogie Development Plan 2019 - 2022 Vision ‘an engaged, vibrant and successful camogie section in Kilmacud Crokes – 2019 - 2022’ Camogie Development Ecosystem; 5 Development Themes Pursuit of Camogie Excellence Funding, Underpinning everything we do: Part of the Structure & ➢ Participation Community Resources ➢ Inclusiveness ➢ Involvement ➢ Fun ➢ Safety Schools as Active part of the Volunteers Wider Club • A player centric approach based on enjoyment, skill development and sense of belonging provided in a safe and friendly environment • All teams are competitive at their age groups and levels • Senior A team competitive in Senior 1 league and championship • All players reach their full potential as camogie players • Players and mentors enjoy the Kilmacud Crokes Camogie Experience • Develop strong links to the local schools and broader community • Increase player numbers so we have a minimum of 40 girls per squad OBJECTIVES • Prolong girls participation in camogie (playing, mentoring, refereeing) • Minimize drop-off rates • Mentors coaching qualifications are current and sufficient for the level/age group • Mentors are familiar with best practice in coaching • Well represented in Dublin County squads, from the Academy up to the Senior County team • More parents enjoying attending and supporting our camogie teams Milestones in Kilmacud Crokes Camogie The Camogie A dedicated section was nursery started U16 Division 1 Teams went from started in 1973 by County 12 a side to 15 a Promoted Eileen Hogan Champions Bunny Whelan side- camogie in -

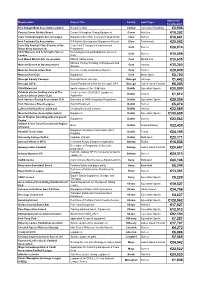

Grid Export Data

Amount to Organisation Project Title County Sport Type be allocated Irish Dragon Boat Association Limited Buoyancy Aids Carlow Canoeing / Kayaking €3,998 County Cavan Athletic Board Cavan / Monaghan Timing Equipment Cavan Athletics €19,302 Clare Schoolboy/girls Soccer League Equipment for CSSL newly purchased facility Clare Soccer €18,841 Irish Taekwon-Do Association ITA Athlete Development Equipment Project Clare Taekwondo €20,042 Cork City Football Club (Friends of the Cork City FC Equipment Improvement Cork Soccer Rebel Army Society Ltd) Programme €28,974 Cork Womens and Schoolgirls Soccer Increasing female participation in soccer in Cork Soccer League Cork €10,599 Irish Mixed Martial Arts Association IMMAF Safety Arena Cork Martial Arts €10,635 Munster Hockey Funding for Equipment and Munster Branch of Hockey Ireland Cork Hockey Storage €35,280 Munster Cricket Union CLG Increase facility standards in Munster Cork Cricket €29,949 Munster Kart Club Equipment Cork Motor Sport €2,700 Donegal County Camogie Donegal Senior camogie Donegal Camogie €1,442 Donegal LGFA Sports Equipment & Kits for Donegal LGFA Donegal Ladies Gaelic Football €8,005 ChildVision Ltd sports equipment for ChildVision Dublin Equestrian Sports €30,009 Cricket Leinster (trading name of The Cricket Leinster 2020/2021 Equipment Dublin Cricket Leinster Cricket Union CLG) Application €1,812 Irish Harness Racing Association CLG Extension of IHRA Integration Programme Dublin Equestrian Sports €29,354 Irish Homeless Street Leagues Sports Equipment Dublin Soccer €5,474 Leinster -

Intramural Broomball Rules

University of Illinois · Campus Recreation · Intramural Activities· www.campusrec.illinois.edu/intramurals ARC Administrative Offices 1430 · (217) 244-1344 INTRAMURAL BROOMBALL RULES Men's, Women's, and Co-Rec Broomball is a game very much like hockey. Most hockey rules apply, except that the game is played with a regulation broomball stick (which is shaped like a broom) and a regulation broomball (which is a heavy plastic ball, slightly bigger than a softball). Campus Recreation provides sticks and balls. The game is played on an ice hockey rink. Players are not allowed to wear skates. Campus Recreation reserves the right to revise, or update, at any time, any rules related to intramural broomball. A. Players' Equipment 1. Footwear: Rubber soled non-marking tennis or basketball type shoes suitable for running on ice are recommended. No spikes, cleats, heavy boots, or similar footwear is allowed. Broomball shoes are not allowed. 2. Gloves, shin pads, elbow pads, and mouthpiece are optional, but recommended. Shin pads or elbow pads must be worn under clothing. Hockey goalie equipment, with the exception of a goalie helmet, are not allowed. Hand protection is limited to the use of mittens or gloves. Helmets are mandatory and will be provided by Campus Recreation. You may use your own helmet if you have one. 3. Balls and sticks will be provided by Campus Recreation and must be used. You may not use your own broomball stick. 4. Broomball adheres to the Intramural Handbook’s jersey policy. Please plan accordingly. 5. All jewelry must be removed. B. Officials 1. The officials shall not permit any player to wear equipment that, in their judgment is dangerous to other players.