Archaeological Investigations in St John's, Worcester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Investigations in St John's, Worcester

Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report No.4 Archaeological Investigations in ST JOHN’S WORCESTER Jo Wainwright Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report no 4 Archaeological Investigations in St John’s, Worcester (WCM 101591) Jo Wainwright With contributions by Ian Baxter, Hilary Cool, Nick Daffern, C Jane Evans, Kay Hartley, Cathy King, Elizabeth Pearson, Roger Tomlin, Gaynor Western and Dennis Williams Illustrations by Carolyn Hunt and Laura Templeton 2014 Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report no 4 Archaeological Investigations in St John’s, Worcester Published by Worcestershire Archaeology Archive & Archaeology Service, The Hive, Sawmill Walk, The Butts, Worcester. WR1 3PD ISBN 978-0-9929400-4-1 © Worcestershire County Council 2014 Worcestershire ,County Council County Hall, Spetchley Road, Worcester. WR5 2NP This document is presented in a format for digital use. High-resolution versions may be obtained from the publisher. [email protected] Front cover illustration: view across the north-west of the site, towards Worcester Cathedral to previous view Contents Summary ..........................................................1 Background ..........................................................2 Circumstances of the project ..........................................2 Aims and objectives .................................................3 The character of the prehistoric enclosure ................................3 The hinterland of Roman Worcester and identification of survival of Roman landscape -

Download This Walk As A

Walk Six - Ledbury and Eastnor • 5.2 mile moderate ramble, one stile only • Disused canal, dismantled railway, town, village, views • OS Map - Malvern Hills and Bredon Hill (Explorer 190) The Route 1. Ledbury, Bye Street, opposite Market House. HR8 1BU. Return from either car park into Bye Street. Walk away from town centre past fire brigade and Brewery Inn. Find the Ledbury Town Trail information board in Queen’s Walk in the public gardens, formerly Ledbury Town Wharf. TR along the easy footpath, over the footbridge (below Masefield’s Knapp), for ⅔ mile, over road bridge to information board. Cross road. TL under railway bridge. In 40m TR over stile up R edge of orchard to crest, to find gap in top right corner. TR at path junction. Go through kissing gate and TR away from Frith Wood House. Follow path further R over railway in front of house to reach. 2. Knapp Lane. Bear R and immediately L along “No through road” at Upperfields. When reaching a seat, go ahead with fence on right, rather than descending to R, staying ahead downhill between green bench and Dog Hill Information Board at path junction. Descend steps past sub-station, take path ahead, into walled lane, to front of church. TL around church. TR along walled Cabbage Lane. TL past police station frontage. After 175m, cross road into Coneygree Wood. Climb into wood, up 19 wide steps, straight ahead, 16 narrow steps, curving L and R up stony terrain, six steps to path junction. Climb straight ahead. Bear R into field through walkers’ gate. -

Settlement Hierarchy and Social Change in Southern Britain in the Iron Age

SETTLEMENT HIERARCHY AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN IN THE IRON AGE BARRY CUNLIFFE The paper explores aspects of the social and economie development of southern Britain in the pre-Roman Iron Age. A distinct territoriality can be recognized in some areas extending over many centuries. A major distinction can be made between the Central Southern area, dominated by strongly defended hillforts, and the Eastern area where hillforts are rare. It is argued that these contrasts, which reflect differences in socio-economic structure, may have been caused by population pressures in the centre south. Contrasts with north western Europe are noted and reference is made to further changes caused by the advance of Rome. Introduction North western zone The last two decades has seen an intensification Northern zone in the study of the Iron Age in southern Britain. South western zone Until the early 1960s most excavation effort had been focussed on the chaiklands of Wessex, but Central southern zone recent programmes of fieid-wori< and excava Eastern zone tion in the South Midlands (in particuiar Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire) and in East Angiia (the Fen margin and Essex) have begun to redress the Wessex-centred balance of our discussions while at the same time emphasizing the social and economie difference between eastern England (broadly the tcrritory depen- dent upon the rivers tlowing into the southern part of the North Sea) and the central southern are which surrounds it (i.e. Wessex, the Cots- wolds and the Welsh Borderland. It is upon these two broad regions that our discussions below wil! be centred. -

British Camp’), Colwall, Herefordshire

A Conservation Management Plan for Herefordshire Beacon (‘British Camp’), Colwall, Herefordshire Prepared by Peter Dorling, Senior Projects Archaeologist Herefordshire Archaeology, Herefordshire Council Final Version Contact: Peter Dorling Senior Project Archaeologist Herefordshire Archaeology Planning Services PO Box 230 Hereford HR1 2ZB Tel. 01432 383238 Email: [email protected] Contents Introduction 1 Part 1: Characterising the Asset 1.1 Background Information 3 1.2 Environmental Information 4 1.2.1 Physical Location and Access 4 Topography 4 Geology and Soils 4 1.2.2 Cultural, Historical and Archaeological Description of features / asset 5 Previous recording and study 12 National Character Area Description 15 1.2.3 Biological Flora 16 Fauna 17 1.2.4 Recreational use of the site 18 1.2.5 Past management for conservation 19 Part 2: Understanding and evaluating the asset 2.1 Current Understanding 2.1.1 Historical / Archaeological 20 2.2 Gaps in knowledge 2.2.1 Historical / Archaeological 28 2.2.2 Biological 29 2.2.3 Recreation 29 2.3 Statement of significance 2.3.1 Historical / Archaeological 30 2.3.2 Biological 31 2.3.3 Recreation 32 Herefordshire Beacon, Colwall, Conservation Management Plan 2.4 Statement of potential for the gaining of new knowledge 2.4.1 Historical / Archaeological 33 2.4.2 Biological 34 2.4.3 Recreation 34 Part 3: Identifying management objectives and issues 3.1 Site condition, management issues and objectives 3.1.1 Historical / Archaeological 35 3.1.2 Biological 38 3.1.3 Recreation 39 3.2 Aims and ambitions -

Great Malvern Circular Or from Colwall)

The Malvern Hills (Great Malvern Circular) The Malvern Hills (Colwall to Great Malvern) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 20th July 2019 21st July 2019 Current status Document last updated Monday, 22nd July 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2018-2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. The Malvern Hills (Great Malvern Circular or from Colwall) Start: Great Malvern Station or Colwall Station Finish: Great Malvern Station Great Malvern station, map reference SO 783 457, is 11 km south west of Worcester, 165 km north west of Charing Cross, 84m above sea level and in Worcestershire. Colwall station, map reference SO 756 424, is 4 km south west of Great Malvern, 25 km east of Hereford, 129m above sea level and in Herefordshire. -

103. Malvern Hills Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 103. Malvern Hills Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 103. Malvern Hills Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment 1 2 3 White Paper , Biodiversity 2020 and the European Landscape Convention , we North are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are East areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good Yorkshire decision-making framework for the natural environment. & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their West decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape East scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader Midlands partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help West Midlands to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. East of England Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key London drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

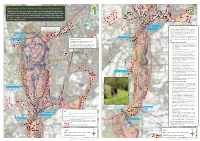

Map-And-Guide-Website-Page-1.Pdf

Welcome to the Malvern Hills and Commons The Malvern Hills and surrounding commons can be explored by the network of footpaths and bridleways that criss-cross this iconic landscape. With unique geology, ancient archaeology, interesting wildlife and spectacular views, use 1 2 this map to help you find your way around the peaks of the Malvern Hills and the wide, open commons. Earnslaw car park A series of waymarked cycling trails Access in a shared landscape Beacon Road car park begin from North Quarry car park. The Malvern Hills and Commons are a shared landscape www.malvernhills.org.uk/visiting/cycling for everyone to enjoy. Hundreds of thousands of visitors come each year to walk, cycle, even hang glide. The Hills Tank Quarry car park are also a working landscape and livestock continue to graze here, cared for by graziers. We work hard to take care of the Hills and Commons for Jubilee Drive car park local people, visitors, local graziers and wildlife. Please help North Quarry car park Arriving by train us to look after this special place by following these simple tips. The Malvern Hills can easily be reached from either Great Malvern or Malvern Link train station. Walking on the Malvern Hills From Great Malvern station, follow a trail designed by • Walkers have a right of access over land under our Route to the Hills which will guide you all the way to the care but we ask you to stick to the main walking paths foot of the Malverns. www.routetothehills.co.uk where possible to avoid disturbance to wildlife and grazing livestock • Please take your litter home with you • Please keep your dog under close control at all times • Take extra care when near livestock. -

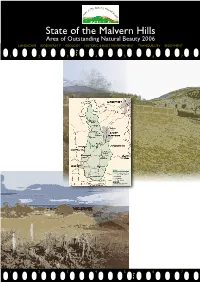

State of the AONB 2006

-292.806 mm State of the Malvern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty 2006 LANDSCAPE BIODIVERSITY GEOLOGY HISTORIC & BUILT ENVIRONMENT TRANQUILLITY ENJOYMENT 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Introduction 1. LANDSCAPE: Fixed-point photography This report provides a snap-shot of the condition of the Malvern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 2006. It does this by presenting information about a range of elements, or attributes, which are deemed to be characteristic of the area. The aim of the report is to provide a baseline of data against which future change can be monitored. When compared with future state of the AONB reports it will also aid decison making and provide a gauge of the effectiveness of the AONB Management Plan Overview: in conserving and enhancing the special qualities of the area. Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a key approach to identifying and describing variation in the character of At the time of writing, work to monitor the condition of designated areas is being developed at the national and local levels. landscapes. This framework is used here to establish an objective programme of fixed point photographic monitoring of change New data sets are being collected and, at the same time, some data are becoming both easier to access and easier to utilise. The throughout the AONB. In this way, subjectivity and cultural bias in the selection of key views, largely based upon scenic beauty and approach to data collection and analysis which has been used to compile the report is intended to be a start, rather than the final knowledge of accessibility, can be avoided. -

Background Information 4

A Conservation Management Plan for Eaton Camp, Ruckhall, Herefordshire Scheduled Ancient Monument, Herefordshire 10 Final version February 2013 Prepared for the Eaton Camp Historical Society by Peter Dorling, Herefordshire Archaeology and Caroline Hanks, Eaton Camp Historical Society Eaton Camp Conservation Management Plan, September 2012 Contents Preamble 2 The Importance and Significance of Eaton Camp 3 Part 1 Description 4 1.1 Background Information 4 1.2 Environmental Information 9 1.2.1 Physical 9 1.2.2 Cultural 10 1.2.3 Biological 20 1.2.4 Recreational use of the site 23 1.2.5 Past management for conservation 23 1.2.6 Site condition, management issues and recommendations 24 1.2.7 Bibliography 30 Part 2 Objectives and Factors Influencing Their Achievement 31 2.1 Long term management objectives 31 2.2 Assessment of factors influencing long term management objectives 31 Part 3 Management Plan 34 3.1 Outline prescriptions and project groups 34 3.2 Project Register 38 Part 4 Summary and Contacts 42 Summary of management issues 42 Further help for landowners 43 1 Eaton Camp Conservation Management Plan, September 2012 Preamble The preparation of a Conservation Management Plan (CMP) for Eaton Camp, an ancient monument scheduled as being of national importance, has been facilitated by the formation of the Eaton Camp Historical Society and their subsequent HLF funded Eaton Camp Conservation project. This project has enabled survey, geophysics and small scale excavation on the site. These have added significantly to our knowledge of the site and confirmed its use in the Iron Age (around 350BC). -

HANLEY MATTERS No

Issue HANLEY MATTERS No. 11 the newsletter of The Hanleys’ Village Society Summer 2006 OFFICERS IRON AGE HILL FORTS President Nick Lechmere Not a lot is known about the doorposts, the smoke from fires Tel: 0771 644927 spectacular Iron Age fortress of dissipating through thatched roofs. Chair British Camp, on the Herefordshire Skilled craftsmen and women would Ian Bowles Beacon, as Deborah Overton have woven clothes coloured by Tel: 311931 pointed out in her talk about the hill plant dyes and made high quality Treasurer forts of Malvern and Bredon. We weapons and jewellery. Outside the John Boardman have no idea exactly when it was fort would have been farms growing Tel: 311748 constructed, who built it, who lived corn and raising chickens in wooden Secretary & Newsletter within its walls, what they did with huts on stilts to protect them from Editor Malcolm Fare their dead (no graves have been predators. Tel: 311197 found) and how long the site was Iron Age forts were centres of Archaeological Officer used. But it is certainly impressive. trade and the British Camp tribe Peter Ewence The earliest enclosure, known as would have known the occupants of Tel: 561702 the citadel, is perhaps 2200-2500 other hill forts, like the three at Programme Secretary years old and covers an area of about Bredon Hill. Of these Kemerton David Thomas 8 acres. A second phase added Camp is the most distinctive, with Tel: 310437 ramparts that followed the contours of an entrance shaped like a pair of the hill and expanded the site to some horns, filtering people through FORTHCOMING ACTIVITIES 33 acres, including a spring. -

The Glosarch/Cleeve Common Trust Self-Guided Archaeological Walk Around Cleeve Common

The GlosArch/Cleeve Common Trust self-guided archaeological walk around Cleeve Common. Cleeve Common, the highest point on the Cotswold escarpment, looks over the Severn Valley towards the Malvern Hills and the Forest of Dean to the west, with the Welsh hills beyond. Cleeve Common covers over 500 hectares (1300 acres), the largest area of Common land in Gloucestershire and its boundaries have survived largely intact for 1000 years. Evidence of human activity on Cleeve Common can be traced back some 6000 years, with flint scatters and at least one possible Neolithic long barrow. There are also traces of Bronze Age (2450-650 BCE) occupation, and the large hilltop enclosure on nearby Nottingham Hill was probably constructed in the Late Bronze Age, around 800 BCE. As we shall see, the bulk of the evidence of prehistoric occupation dates to the Iron Age (650BCE-43AD) with sites on the hill and below the escarpment. No Roman remains have so far been found on the Common, but excavations at nearby Haymes in the 1980s by Bernard and Barbara Rawes found evidence of occupation between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD. In addition, Cleeve Common shows archaeological evidence of Medieval and post-Medieval industry, farming and recreation. This walk takes you around many of the key sites on Cleeve Common. The walk starts at the Quarry Car Park (*). The car park is reached by the lane off the B4632 from Prestbury to Winchcombe, which is signposted to the golf club. Pass through the gate at the top of the lane and turn left into the car park. -

L06-2135-10B-Historic Viewpoi

LEGEND Malvern Hills AONB (Note 2) Dodderhill Roman Fort Cotswold AONB (Note 2) Garmsley Hill Fort Wye Valley AONB (Note 2) 10km Roman Fort at Coppice House Distance from spine of Malvern Hills 1 Wall Hills Camp Fort at Berrow Hill Scheduled fort: used as visual 1 receptor (Notes 2 and 3) Other scheduled fort (Notes 2 and 3) Risbury Camp Scheduled castle: not used as visual receptor (Notes 2 and 3) 1 Scheduled ancient monument within the Malvern Hills AONB: not used as visual receptor 15km Other historic forts: used as 1 visual receptor (Note 4) Other historic forts (Note 4) Notes: 1. Viewpoints have been selected to be representative, and are not definitive 10km 2. Taken from www.cotswoldaonb.com website, Malvern Hills District Council Local Plan Adopted 12th July 2006, Forest of Dean District Local Plan Review Castle Frome Adopted November 2005, Herefordshire Unitary Development Plan Adopted 23rd March 2007 and wyevalleyaonb.org.uk website 3.Taken from the Tewkesbury Borough Local Plan, Roman Fort, SW of Canon Frome March 2006, Wychavon District Local Plan Adopted June 2006 and Historic Herefordshire Online website www.smr.herefordshire.gov.uk Hanley Castle 4. As shown on the Ordnance Survey Explorer map 190 Elmley Castle British Camp 49 Little Malvern Priory 10km 4 Fort at Bredon Hill Kilbury Camp Wall Hills Camp Midsummer Hill Camp Hollybush Towbury Hill camp B Photographs re-numbered SH JJ JJ 17.3.09 A Minor amendments SH JJ JJ 25.2.09 Cherry Hill Camp L06 Oldbury Camp The Knolls Camp Dixton Hill Camp Fort near Eldersfield Langley Hill Nottingham Hill Camp MALVERN HILLS AONB VIEWS PROJECT HISTORIC VIEWPOINTS 15km Cleeve Cloud Wilton Castle As shown Dec 08 SH JJ JJ Goodrich Castle 2135/10B Scale © Crown Copyright.