Chinese Housing and the Transformation of Uyghur Domestic Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Thoroughly Reforming Them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude"

By Adrian Zenz - Version of this paper accepted for publication by the journal Central Asian Survey "Thoroughly Reforming Them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude" - China's Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang1 Adrian Zenz European School of Culture and Theology, Korntal Updated September 6, 2018 This is the accepted version of the article published by Central Asian Survey at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02634937.2018.1507997 Abstract Since spring 2017, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China has witnessed the emergence of an unprecedented reeducation campaign. According to media and informant reports, untold thousands of Uyghurs and other Muslims have been and are being detained in clandestine political re-education facilities, with major implications for society, local economies and ethnic relations. Considering that the Chinese state is currently denying the very existence of these facilities, this paper investigates publicly available evidence from official sources, including government websites, media reports and other Chinese internet sources. First, it briefly charts the history and present context of political re-education. Second, it looks at the recent evolution of re-education in Xinjiang in the context of ‘de-extremification’ work. Finally, it evaluates detailed empirical evidence pertaining to the present re-education drive. With Xinjiang as the ‘core hub’ of the Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing appears determined to pursue a definitive solution to the Uyghur question. Since summer 2017, troubling reports emerged about large-scale internments of Muslims (Uyghurs, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz) in China's northwest Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). By the end of the year, reports emerged that some ethnic minority townships had detained up to 10 percent of the entire population, and that in the Uyghur-dominated Kashgar Prefecture alone, numbers of interned persons had reached 120,000 (The Guardian, January 25, 2018). -

CHINA: HUMAN RIGHTS CONCERNS in XINJIANG a Human Rights Watch Backgrounder October 2001

350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor New York, NY 10118 Phone: 212-290-4700 Fax: 212-736-1300 E-mail:[email protected] Website:http://www.hrw.org CHINA: HUMAN RIGHTS CONCERNS IN XINJIANG A Human Rights Watch Backgrounder October 2001 Xinjiang after September 11 In the wake of the September 11 attacks on the United States, the People’s Republic of China has offered strong support for Washington and affirmed that it "opposes terrorism of any form and supports actions to combat terrorism." Human Rights Watch is concerned that China’s support for the war against terrorism will be a pretext for gaining international support—or at least silence—for its own crackdown on ethnic Uighurs in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Beijing has long claimed to be confronted with “religious extremist forces” and “violent terrorists” in Xinjiang, a vast region one-sixth of China’s land area. Xinjiang has a population of 18 million and is home to numerous Turkic-speaking Muslim ethnic groups, of which the Uighurs, numbering eight million, are the largest. (The second largest group is the Kazakhs, with 1.2 million.) The percentage of ethnic Chinese (Han) in the population has grown from 6 percent in 1949 to 40 percent at present, and now numbers some 7.5 million people. Much like Tibetans, the Uighurs in Xinjiang, have struggled for cultural survival in the face of a government- supported influx by Chinese migrants, as well as harsh repression of political dissent and any expression, however lawful or peaceful, of their distinct identity. Some have also resorted to violence in a struggle for independence Chinese authorities have not discriminated between peaceful and violent dissent, however, and their fight against “separatism” and “religious extremism” has been used to justify widespread and systematic human rights violations against Uighurs, including many involved in non-violent political, religious, and cultural activities. -

Writing Uyghur Women Into the Chinese Nation

LEGIBLE CITIZENS: WRITING UYGHUR WOMEN INTO THE CHINESE NATION Arianne Ekinci A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the History Department in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved By: Michael Tsin Michelle King Cemil Aydin © 2019 Arianne Ekinci ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Arianne Ekinci: Legible Citizens: Writing Uyghur Women into the Chinese Nation (Under the direction of Michael Tsin) It’s common knowledge that the People’s Republic of China was established as a multi- ethnic state in 1949. But what did this actually mean for populations at the fringes of the new nation? This thesis uses sources from the popular press read against official publications to tease out the implications of state policies and examine exactly how the state intended to incorporate Uyghur women into the Chinese nation, and how these new subjects were intended to embody the roles of woman, ethnic minority, and Chinese citizen. While official texts are repositories of ideals, texts from the popular press attempt to graph these ideals onto individual narratives. In this failure to perfectly accord personal encounters with CCP ideals, these authors create a narrative fissure in which it is possible to see the implications of official minority policy. Focusing on three central stories from the popular press, this thesis probes into the assumptions held concerning the manifestation of Uyghur citizenship and the role of Uyghur women as subjects of the Chinese state as seen through intended relationships with Han women, Uyghur men, party apparati, the public eye, and civil law. -

Violent Resistance in Xinjiang (China): Tracking Militancy, Ethnic Riots and ‘Knife- Wielding’ Terrorists (1978-2012)

HAO, Núm. 30 (Invierno, 2013), 135-149 ISSN 1696-2060 VIOLENT RESISTANCE IN XINJIANG (CHINA): TRACKING MILITANCY, ETHNIC RIOTS AND ‘KNIFE- WIELDING’ TERRORISTS (1978-2012) Pablo Adriano Rodríguez1 1University of Warwick (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Recibido: 14 Octubre 2012 / Revisado: 5 Noviembre 2012 / Aceptado: 10 Enero 2013 / Publicación Online: 15 Febrero 2013 Resumen: Este artículo aborda la evolución The stability of Xinjiang, the northwestern ‘New de la resistencia violenta al régimen chino Frontier’ annexed to China under the Qing 2 en la Región Autónoma Uigur de Xinjiang dynasty and home of the Uyghur people –who mediante una revisión y análisis de la officially account for the 45% of the population naturaleza de los principales episodios in the region- is one of the pivotal targets of this expenditure focused nationwide on social unrest, violentos, en su mayoría con connotaciones but specifically aimed at crushing separatism in separatistas, que han tenido lugar allí desde this Muslim region, considered one of China’s el comienzo de la era de reforma y apertura “core interests” by the government3. chinas (1978-2012). En este sentido, sostiene que la resistencia violenta, no In Yecheng, attackers were blamed as necesariamente con motivaciones político- “terrorists” by Chinese officials and media. separatistas, ha estado presente en Xinjiang ‘Extremism, separatism and terrorism’ -as en la forma de insurgencia de baja escala, defined by the rhetoric of the Shanghai revueltas étnicas y terrorismo, y Cooperation Organization (SCO)- were invoked probablemente continúe en el futuro again as ‘evil forces’ present in Xinjiang. teniendo en cuenta las fricciones existentes Countering the Chinese official account of the events, the World Uyghur Congress (WUC), a entre la minoría étnica Uigur y las políticas Uyghur organization in the diaspora, denied the llevadas a cabo por el gobierno chino. -

Save the Children in China 2013 Annual Review

Save the Children in China 2013 Annual Review Save the Children in China 2013 Annual Review i CONTENTS 405,579 In 2013, Save the Children’s child education 02 2013 for Save the Children in China work helped 405,579 children and 206,770 adults in China. 04 With Children and For Children 06 Saving Children’s Lives 08 Education and Development 14 Child Protection 16 Disaster Risk Reduction and Humanitarian Relief 18 Our Voice for Children 1 20 Media and Public Engagement 22 Our Supporters Save the Children organised health and hygiene awareness raising activities in the Nagchu Prefecture of Tibet on October 15th, 2013 – otherwise known as International Handwashing Day. In addition to teaching community members and elementary school students how to wash their hands properly, we distributed 4,400 hygiene products, including washbasins, soap, toothbrushes, toothpastes, nail clippers and towels. 92,150 24 Finances In 2013, we responded to three natural disasters in China, our disaster risk reduction work and emergency response helped 92,150 Save the Children is the world’s leading independent children and 158,306 adults. organisation for children Our vision A world in which every child attains the right to survival, protection, development and 48,843 participation In 2013, our child protection work in China helped 48,843 children and 75,853 adults. Our mission To inspire breakthroughs in the way the world treats children, and to achieve immediate and 2 lasting change in their lives Our values 1 Volunteers cheer on Save the Children’s team at the Beijing Marathon on October 20th 2013. -

Sacred Right Defiled: China’S Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom

Sacred Right Defiled: China’s Iron-Fisted Repression of Uyghur Religious Freedom A Report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project Table of Contents Executive Summary...........................................................................................................2 Methodology.......................................................................................................................5 Background ........................................................................................................................6 Features of Uyghur Islam ........................................................................................6 Religious History.....................................................................................................7 History of Religious Persecution under the CCP since 1949 ..................................9 Religious Administration and Regulations....................................................................13 Religious Administration in the People’s Republic of China................................13 National and Regional Regulations to 2005..........................................................14 National Regulations since 2005 ...........................................................................16 Regional Regulations since 2005 ..........................................................................19 Crackdown on “Three Evil Forces”—Terrorism, Separatism and Religious Extremism..............................................................................................................23 -

Living on the Margins: the Chinese State’S Demolition of Uyghur Communities

Living on the Margins: The Chinese State’s Demolition of Uyghur Communities A Report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................3 II. Background.................................................................................................................................4 III. Legal Instruments ....................................................................................................................16 IV. Peaceful Resident, Prosperous Citizen; the Broad Scope of Demolition Projects throughout East Turkestan.............................................................................................................29 V. Kashgar: An In-Depth Look at the Chinese State’s Failure to Protect Uyghur Homes and Communities...........................................................................................................................55 VI. Transformation and Development with Chinese Characteristics............................................70 VII. Recommendations..................................................................................................................84 VIII. Appendix: Results of an Online Survey Regarding the Demolition of Kashgar Old City ................................................................................................................................................86 IX. Acknowledgments...................................................................................................................88 -

Yining City, China PREVENTING MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION of HIV, SYPHILIS and HEPATITIS B

BEST PRACTICES OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PREVENTING MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION OF HIV, SYPHILIS AND HEPATITIS B Yining City, China Best Practices of Community Engagement: Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV, Syphilis and Hepatitis B, Yining City, China Photo credits Cover: © Shutterstock/Lifebrary Page iv: © UNICEF China/2017/Xu Wenqing Page 1: © UNICEF China/2017/Xu Wenqing Page 2: © UNICEF China/2017/Xu Wenqing Page 5: © UNICEF China/2017/Xu Wenqing Page 8: © Shutterstock/everytime Page 11: © Shutterstock/RONNACHAIPARK Page 15: © Shutterstock/GOLFX Page 19: © Shutterstock/Grigvovan Page 22: © Shutterstock/chinahbzyg November 2018 UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office P.O. Box 2-154 Bangkok 10200 Thailand Telephone: (662) 356-9499 Fax: (662) 280-3563 Email: [email protected] www.unicef.org/eap BEST PRACTICES OF COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PREVENTING MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION OF HIV, SYPHILIS AND HEPATITIS B Yining City, China ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This best practice report was compiled with the support of several key entities. The report would not have been possible without the invaluable support of Dr. Sha Wuli, Xinjiang Provincial EMTCT implementation team leader, Xinjiang Provincial Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Mr. Wang Haihong, Deputy director of Yining Bureau of Health and Family Planning, Dr. Ma Yueli, Director of Yining city Maternal Child Health hospital and her team on EMTCT, including members of the China National Committee for the Care of Children (CNCCC), township and village level focal points. Also, our sincere thanks to the women living with HIV peer support group members in Kaerdun and Tashikule townships in Yining. We take this opportunity to sincerely thank, Dr. -

36496 Federal Register / Vol

36496 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 130 / Monday, July 12, 2021 / Rules and Regulations compensation is provided solely for the under forty-three entries to the Entity Committee (ERC) to be ‘military end flight training and not the use of the List. These thirty-four entities have been users’ pursuant to § 744.21 of the EAR. aircraft. determined by the U.S. Government to That section imposes additional license The FAA notes that any operator of a be acting contrary to the foreign policy requirements on, and limits the limited category aircraft that holds an interests of the United States and will be availability of, most license exceptions exemption to conduct Living History of listed on the Entity List under the for, exports, reexports, and transfers (in- Flight (LHFE) operations already holds destinations of Canada; People’s country) to listed entities on the MEU the necessary exemption relief to Republic of China (China); Iran; List, as specified in supplement no. 7 to conduct flight training for its flightcrew Lebanon; Netherlands (The part 744 and § 744.21 of the EAR. members. LHFE exemptions grant relief Netherlands); Pakistan; Russia; Entities may be listed on the MEU List Singapore; South Korea; Taiwan; to the extent necessary to allow the under the destinations of Burma, China, exemption holder to operate certain Turkey; the United Arab Emirates Russia, or Venezuela. The license aircraft for the purpose of carrying (UAE); and the United Kingdom. This review policy for each listed entity is persons for compensation or hire for final rule also revises one entry on the identified in the introductory text of living history flight experiences. -

DC: PRC: Xinjiang Altay Urban Infrastructure and Environment

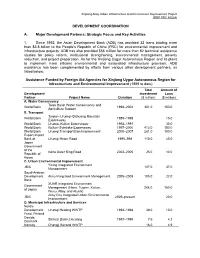

Xinjiang Altay Urban Infrastructure and Environment Improvement Project (RRP PRC 43024) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Focus and Key Activities 1. Since 1992, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has provided 32 loans totaling more than $3.8 billion to the People's Republic of China (PRC) for environmental improvement and infrastructure projects. ADB has also provided $56 million for more than 82 technical assistance studies for policy reform, institutional strengthening, environmental management, poverty reduction, and project preparation. As for the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and its plans to implement more efficient environmental and associated infrastructure provision, ADB assistance has been complemented by efforts from various other development partners, as listed below. Assistance Funded by Foreign Aid Agencies for Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region for Infrastructure and Environmental Improvement (1989 to date) Total Amount of Development Investment Loan Partner Project Name Duration ($ million) ($ million) A. Water Conservancy Tarim Basin Water Conservancy and World Bank 1998–2004 301.0 150.0 Agriculture Support B. Transport Turpan–Urumqi–Dahuang Mountain World Bank 1989–1998 15.0 Expressway World Bank Urumqi–Kuitun Expressway 1992–1997 30.0 World Bank Kuitun–Syimlake Expressway 1997–2000 413.0 150.0 World Bank Urumqi Transportation Improvement 2000–2007 281.0 100.0 Export-Import Bank of Urumqi Hetan Road 1995–998 110.0 45.0 Japan Government of the Korla Outer Ring Road 2003–2005 25.0 10.0 Republic of Korea C. Urban Environmental Improvement Yining Integrated Environment JBIC 107.0 37.0 Management Saudi Arabian Development Aksu Integrated Environment Management 2005–2008 105.0 22.0 Bank XUAR Integrated Environment Government Management (Hami, Turpan, Kuitun, 206.0 150.0 of Japan Wusu, Altay, and Atushi) Altay City Integrated Urban Environmental JBIC 2009–present 20.0 Improvement D. -

Staking Claims to China's Borderland: Oil, Ores and State- Building In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Staking Claims to China’s Borderland: Oil, Ores and State- building in Xinjiang Province, 1893-1964 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Judd Creighton Kinzley Committee in charge: Professor Joseph Esherick, Co-chair Professor Paul Pickowicz, Co-chair Professor Barry Naughton Professor Jeremy Prestholdt Professor Sarah Schneewind 2012 Copyright Judd Creighton Kinzley, 2012 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Judd Creighton Kinzley is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-chair Co- chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgments.............................................................................................................. vi Vita ..................................................................................................................................... ix Abstract ................................................................................................................................x Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 -

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ......................................................................................................................................................