The Ganga Water Science and Technology Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F. No. A-12032/1/2020-Estbt.(FBP)/1720 (We) Date: 12.10.2020

F. No. A-12032/1/2020-Estbt.(FBP)/1720 (we) Date: 12.10.2020 NOTIFICATION FARAKKA BARRAGE PROJECT H. S. SCHOOL, FARAKKA P.O-Farakka Barrage, Dist-Murshidabad, W.B., Pin-742212 Farakka Barrage Project Higher Secondary (FBPHS) School (A Bengali medium School) wants to prepare a panel of selected candidates for the “academic session-2021” for the following posts to engage them on purely part time contractual basis through walk-in interview. Sl. Name of Post Essential Qualification (*) No. of No. posts 1. Post Graduate (A) Master‟s Degree with 50% marks in the relevant Eight Teacher (PGT) subject from a recognized University or Institute. (08) {Maths-2, English-1, (B) Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) from a recognized Biology (Botany- University or Institute. 1,Zoology-1), Chemistry-1, Physics-1, Geography-1 } 2. Trained Graduate (A) Graduation or Four year degree of Bachelor of Arts Six Teacher (TGT) {Pure & Education (B.A.Ed) or Bachelor of Science and (06) Science-2, Bio- Education (B.Sc.Ed) with 50% marks (with Science-1, English- concerned subject as a compulsory subject in 1, History-1, Hindi- graduation) from a recognized University or 1}. Institute. (B) Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) (C) Qualified CTET (Elementary stage)/ TET (Upper Primary. Level}. 3. TGT (Male Physical (A) Graduate in Physical Education or B. P Ed. from a Two Training Instructor- recognized University or Institute, with minimum 50% (02) 1;Female Physical marks. Training Instructor- 1) 4. TGT (Music)(Vocal) (A) Graduate in Music (Vocal) from a recognized One University or Institute, with minimum 50% marks. -

Title of the Project: Monitoring of Migratory Birds at Selected Water Bodies of Murshidabad District

REPORT ON THE PROJECT 2020 Title of the project: Monitoring of Migratory Birds at selected water bodies of Murshidabad district Submitted by Santi Ranjan Dey Department of Zoology, Rammohan College, 102/1, Raja Rammohan Sarani, Kolkata 09 2020 REPORT ON THE PROJECT Title of the project: Monitoring of Migratory Birds at selected water bodies of Murshidabad District: Introduction: The avian world has always been a fascination to the human world and has been a subject of our studies. Mythological documents hold a number of examples of birds being worshiped as goods with magical powers by the ancient civilizations. Even today winged wonders continue to be the subject of our astonishment primarily because of their ability to fly, their ability to build extraordinarily intricate nests, and of course, the brilliant colour of their plumage – features that no human being can replicate. Taxonomically birds are categorized in “Orders” “Families” and “Genera” and “species”. But overall they are divided into two groups: Passeriformes (or Passerines) and Non Passeriformes (non passerines). At least 60% of all bird species are Passeriformes or song birds, their distinguishing characteristics being their specialized leg structure, vocal structure and brain-wiring which allows them to produce complex songs. The non- passerine comprises 28 out of 29 orders of birds in the world. Throughout the world approximately 11,000 species are found. India is having 1301 species. West Bengal has 57.69% of the total avian fauna (750 species). Though there are many nomenclatures used by different people, we followed “Standardized common and scientific names of birds of Indian subcontinent by Manakadan and Pittie (2001).” Identification of bird is generally based on combination of various characteristics. -

Situation Analysis on Inland Navigation

0 +" 0 +" !) =*9 )9 !0 79 %!* #9 #!1 "0!)0 +! )! 0!" # "!"9>)% !! ) <(/ 0 )! >9!! # )! *!9/ 0 *> )! !5>9! # > 7)!+!9 )! >9 # %%!9" )! !" # %9/ !999/ 0*9/ 9 %%!9" )! 0!* # #9!9 9 <09!8 )! +!7 !5>9!!0 ) ><% 9! )9W >!9 +!7 0 0 !%!9 9!a!% )! # 8 ) +! >>9!0 < )! !9 #9 9>! ##9 0 !9 >!9/ )! !)!908 A<)!0 <1 !" #`%!B "0!) 9 #`%!B 0 9 #`%!B 0/ 7C!90 >9")1 + 3.-3 / !9 #9 !9+ # 9! 0 9 !9%! !>90% # ) ><% #9 !0% 9 )!9 %**!9% >9>! )9C!0 7) >99 79! >!9* #9* )! %>9") )0!9 >9+0!0 )! 9%! # %(7!0"!08 !>90% # ) ><% #9 9!! 9 )!9 %**!9% >9>! >9)<!0 7) >99 79! >!9* # )! %>9") )0!98 1 )9/ 8 =8 0 / 8 8 E3.-3F / %!* #9 #!1 "0!)0 +!/ / !9 #9 !9+ # 9!8 A9G!% !*1 !) A"9!/ 9( + 0!9 (/ )9 )/ =C*00 )*!0 09 0!"1 A90> ) > !0"1 A9> A0! +!9 A) <1 <0 H* +!9 0!" <1 )!() 0CC* 0 8 I8 8 J<09 )* +<! #9*1 E!9 #9 !9+ # 9!F !" #`%!/ "(( "0!) 9 #`%!/ )( 0 9 #`%!/ !7 !) 7778%89": 4 0#$!# Bangladesh and India share three major river systems: the Ganga, the Brahmaputra and the Meghna. Along with their tributaries, these rivers drain about 1.75 million sq km of land, with an average runoff of 1,200 cu km. The GBM system also supports over 620 million people. Thus, the need for cooperation on trans-boundary waters is crucial to the future well-being of these millions. That is precisely the motivation for the Ecosystems for Life: A Bangladesh- India Initiative (Dialogue for Sustainable Management of Trans-boundary Water Regimes in South Asia) project. -

The National Waterway (Allahabad-Haldia Stretch of the Ganga- Bhagirathi-Hooghly River) Act, 1982 ______Arrangement of Sections ______Sections 1

THE NATIONAL WATERWAY (ALLAHABAD-HALDIA STRETCH OF THE GANGA- BHAGIRATHI-HOOGHLY RIVER) ACT, 1982 _________ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS _________ SECTIONS 1. Short title and commencement 2. Declaration of a certain stretch of Ganga-Bhagirathi-Hooghly river to be national waterway. 3. Declaration as to expediency of control by the Union of Ganga-Bhagirathi-Hooghly river for certain purposes. 4. [Omitted.] 5. [Omitted.] 6. [Omitted.] 7. [Omitted.] 8. [Omitted.] 9. [Omitted.] 10. [Omitted.] 11. [Omitted.] 12. [Omitted.] 13. [Omitted.] 14. [Omitted.] 15. [Omitted.] THE SCHEDULE. 1 THE NATIONAL WATERWAY (ALLAHABAD-HALDIA STRETCH OF THE GANGA- BHAGIRATHI-HOOGHLY RIVER) ACT, 1982 ACT NO. 49 OF 1982 [18th October, 1982.] An Act to provide for the declaration of the Allahabad-Haldia Stretch of the Ganga-Bhagirathi-Hooghly river to be a national waterway and also to provide for the regulation and development of that river for purposes of shipping and navigation on the said waterway and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Thirty-third Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. Short title and commencement.—(1) This Act may be called The National Waterway (Allahabad- Haldia Stretch of the Ganga-Bhagirathi-Hooghly River) Act, 1982. (2) It shall come into force on such dateas the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. 2. Declaration of a certain stretch of Ganga-Bhagirathi-Hooghly river to be national waterway.—The Allahabad-Haldia Stretch of the Ganga-Bhagirathi-Hooghly river, the limits of which are specified in the Schedule, is hereby declared to be a national waterway. -

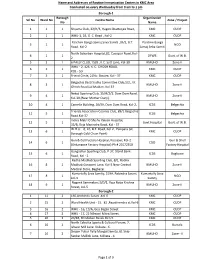

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

Slowly Down the Ganges March 6 – 19, 2018

Slowly Down the Ganges March 6 – 19, 2018 OVERVIEW The name Ganges conjures notions of India’s exoticism and mystery. Considered a living goddess in the Hindu religion, the Ganges is also the daily lifeblood that provides food, water, and transportation to millions who live along its banks. While small boats have plied the Ganges for millennia, new technologies and improvements to the river’s navigation mean it is now also possible to travel the length of this extraordinary river in considerable comfort. We have exclusively chartered the RV Bengal Ganga for this very special voyage. Based on a traditional 19th century British design, our ship blends beautifully with the timeless landscape. Over eight leisurely days and 650 kilometres, we will experience the vibrant, complex tapestry of diverse architectural expressions, historical narratives, religious beliefs, and fascinating cultural traditions that thrive along the banks of the Ganges. Daily presentations by our expert study leaders will add to our understanding of the soul of Indian civilization. We begin our journey in colourful Varanasi for a first look at the Ganges at one of its holiest places. And then by ship we explore the ancient Bengali temples, splendid garden-tombs, and vestiges of India’s rich colonial past and experience the enduring rituals of daily life along ‘Mother Ganga’. Our river journey concludes in Kolkatta (formerly Calcutta) to view the poignant reminders of past glories of the Raj. Conclude your trip with an immersion into the lush tropical landscapes of Tamil Nadu to visit grand temples, testaments to the great cultural opulence left behind by vanished ancient dynasties and take in the French colonial vibe of Pondicherry. -

The Conservation Action Plan the Ganges River Dolphin

THE CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN FOR THE GANGES RIVER DOLPHIN 2010-2020 National Ganga River Basin Authority Ministry of Environment & Forests Government of India Prepared by R. K. Sinha, S. Behera and B. C. Choudhary 2 MINISTER’S FOREWORD I am pleased to introduce the Conservation Action Plan for the Ganges river dolphin (Platanista gangetica gangetica) in the Ganga river basin. The Gangetic Dolphin is one of the last three surviving river dolphin species and we have declared it India's National Aquatic Animal. Its conservation is crucial to the welfare of the Ganga river ecosystem. Just as the Tiger represents the health of the forest and the Snow Leopard represents the health of the mountainous regions, the presence of the Dolphin in a river system signals its good health and biodiversity. This Plan has several important features that will ensure the existence of healthy populations of the Gangetic dolphin in the Ganga river system. First, this action plan proposes a set of detailed surveys to assess the population of the dolphin and the threats it faces. Second, immediate actions for dolphin conservation, such as the creation of protected areas and the restoration of degraded ecosystems, are detailed. Third, community involvement and the mitigation of human-dolphin conflict are proposed as methods that will ensure the long-term survival of the dolphin in the rivers of India. This Action Plan will aid in their conservation and reduce the threats that the Ganges river dolphin faces today. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. R. K. Sinha , Dr. S. K. Behera and Dr. -

National Ganga River Basin Authority (Ngrba)

NATIONAL GANGA RIVER BASIN AUTHORITY (NGRBA) Public Disclosure Authorized (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Volume I - Environmental and Social Analysis March 2011 Prepared by Public Disclosure Authorized The Energy and Resources Institute New Delhi i Table of Contents Executive Summary List of Tables ............................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1 National Ganga River Basin Project ....................................................... 6 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Ganga Clean up Initiatives ........................................................................... 6 1.3 The Ganga River Basin Project.................................................................... 7 1.4 Project Components ..................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.1 Objective ...................................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.2 Sub Component A: NGRBA Operationalization & Program Management 9 1.4.1.3 Sub component B: Technical Assistance for ULB Service Provider .......... 9 1.4.1.4 Sub-component C: Technical Assistance for Environmental Regulator ... 10 1.4.2.1 Objective ................................................................................................... -

The Hooghly River a Sacred and Secular Waterway

Water and Asia The Hooghly River A Sacred and Secular Waterway By Robert Ivermee (Above) Dakshineswar Kali Temple near Kolkata, on the (Left) Detail from The Descent of the Ganga, life-size carved eastern bank of the Hooghly River. Source: Wikimedia Commons, rock relief at Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, India. Source: by Asis K. Chatt, at https://tinyurl.com/y9e87l6u. Wikimedia Commons, by Ssriram mt, at https://tinyurl.com/y8jspxmp. he Hooghly weaves through the Indi- Hooghly was venerated as the Ganges’s original an state of West Bengal from the Gan- and most sacred route. Its alternative name— ges, its parent river, to the sea. At just the Bhagirathi—evokes its divine origin and the T460 kilometers (approximately 286 miles), its earthly ruler responsible for its descent. Hindus length is modest in comparison with great from across India established temples on the Asian rivers like the Yangtze in China or the river’s banks, often at its confluence with oth- Ganges itself. Nevertheless, through history, er waterways, and used the river water in their the Hooghly has been a waterway of tremen- ceremonies. Many of the temples became fa- dous sacred and secular significance. mous pilgrimage sites. Until the seventeenth century, when the From prehistoric times, the Hooghly at- main course of the Ganges shifted decisively tracted people for secular as well as sacred eastward, the Hooghly was the major channel reasons. The lands on both sides of the river through which the Ganges entered the Bay of were extremely fertile. Archaeological evi- Bengal. From its source in the high Himalayas, dence confirms that rice farming communi- the Ganges flowed in a broadly southeasterly ties, probably from the Himalayas and Indian direction across the Indian plains before de- The Hooghly was venerated plains, first settled there some 3,000 years ago. -

Changing Course of Rivers in Murshidabad Effecting Growth of Development and Features of Some Principal Towns and Socio- Political Outlook

International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management (IJREAM) ISSN : 2454-9150 Vol-05, Issue-02, May 2019 Changing Course of Rivers in Murshidabad Effecting Growth of Development and Features of Some Principal Towns and Socio- Political outlook. Sagar Simlandy, Assistant Professor in History, Sripat Singh College, Jiaganj, Murshidabad, W.B., India. [email protected] Abstract - Murshidabad district of West Bengalis one of such backward districts identified in Human Development Report (HDI-0.46, 2004) and it belongs tothe huge diversity in terms of geographic phenomena. Agriculture isthe predominant economic activities followed by cottage and small industries in the form of Biri, ivory and woodcraft, Indian cork (SHOLA PITH), bell metal (KANSA) and well knownsilk industry. Having a Muslim population of 63.67 percent, Murshidabad considered itself asthe highest Muslim minority concentrated district not only in West Bengal but also in India, Bhagirathi was the main flow of Ganga, hundreds of years ago. The present channel of the Bhagirathi , with its sacred traditions and ruined cities, marks the ancient course of the river Ganga. It was the main trading link between north India and the south Asian countries through the Bay of Bengal, Sir William Willcock said,“The Bhagirathi, The Jalangi and the Mathabhanga as the „overflow irrigation system‟ in Ancient Bengal,” Gradually sitting of Bhagirathi caused it to change its course.. International status of these articles is very important because many ship are came to India by River and relate to foreign trade To study how rivers cause of destruction at the same time construction of village and town and it changes the centre of peoples hope and aspiration and brings social change. -

Download Book

"We do not to aspire be historians, we simply profess to our readers lay before some curious reminiscences illustrating the manners and customs of the people (both Britons and Indians) during the rule of the East India Company." @h£ iooi #ld Jap €f Being Curious Reminiscences During the Rule of the East India Company From 1600 to 1858 Compiled from newspapers and other publications By W. H. CAREY QUINS BOOK COMPANY 62A, Ahiritola Street, Calcutta-5 First Published : 1882 : 1964 New Quins abridged edition Copyright Reserved Edited by AmARENDRA NaTH MOOKERJI 113^tvS4 Price - Rs. 15.00 . 25=^. DISTRIBUTORS DAS GUPTA & CO. PRIVATE LTD. 54-3, College Street, Calcutta-12. Published by Sri A. K. Dey for Quins Book Co., 62A, Ahiritola at Express Street, Calcutta-5 and Printed by Sri J. N. Dey the Printers Private Ltd., 20-A, Gour Laha Street, Calcutta-6. /n Memory of The Departed Jawans PREFACE The contents of the following pages are the result of files of old researches of sexeral years, through newspapers and hundreds of volumes of scarce works on India. Some of the authorities we have acknowledged in the progress of to we have been indebted for in- the work ; others, which to such as formation we shall here enumerate ; apologizing : — we may have unintentionally omitted Selections from the Calcutta Gazettes ; Calcutta Review ; Travels Selec- Orlich's Jacquemont's ; Mackintosh's ; Long's other Calcutta ; tions ; Calcutta Gazettes and papers Kaye's Malleson's Civil Administration ; Wheeler's Early Records ; Recreations; East India United Service Journal; Asiatic Lewis's Researches and Asiatic Journal ; Knight's Calcutta; India. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province.