Pfthpsora Pachyrhizi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Soybean Rust Asian Soybean Rust Is a Serious Disease of Soybeans Caused by the Fungus Phakopsora Pachyrhizi

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory - Invasive Fungi Fact Sheets Asian soybean rust Asian soybean rust is a serious disease of soybeans caused by the fungus Phakopsora pachyrhizi. Until recently this disease did not occur on soybean in the western hemisphere but it spread to South America in 2001 and was found for the first time in North America in November 2004. A second, similar-looking rust fungus, P. meibomiae, also infects soybeans but is much less virulent and occurs primarily in the western hemisphere. It is important to differentiate between these two rust species but this can only be done reliably using molecular techniques. Both P. pachyrhizi and P. meibomiae infect numerous leguminous plant hosts. Phakopsora pachyrhizi Syd. & P. Syd., Ann. Mycol 12:108. 1914 Spermogonia and aecia unknown. Anamorph sori (Malupa-type) amphigenous, mostly hypophyllous, circular, minute, pulverulent, whitish becoming pale cinnamon-brown, scattered or in groups on discolored spots, subepidermal becoming erumpent, cone-like, 1-2 mm diam, surrounded by paraphyses, with a central opening; paraphyses cylindric to clavate, 25-50 × 6-14 µm, slightly thickened at the apex, colorless to pale yellowish-brown; anamorph spores sessile, obovoid to broadly ellipsoidal, 18-37 × 15-24 µm, wall 1-1.5 µm thick, minutely and densely echinulate, colorless to pale yellowish brown, sometimes pale cinnamon-brown in age; germ pores (2) 3-5 (-10), equatorial or scattered on equatorial zone, or occasionally scattered on and above the equatorial zone, usually inconspicuous. Telia hypophyllous, minute, 0.15-0.5 mm across, often intermixed with anamorph sori, chestnut brown to chocolate brown, subepidermal, crustose; teliospores one-celled, irregularly arranged in 2-7 layers, variable in shape, angularly globose, oblong to ellipsoidal (10-) 15-26 × 6-13 µm, wall 1-1.5 µm thick, slightly thickened at the apex (-3 µm), colorless to yellowish brown. -

Asian Soybean Rust in Brazil: Past, Present, and Future

Asian soybean rust in Brazil: past, present, and future Cláudia Vieira Godoy(1), Claudine Dinali Santos Seixas(1), Rafael Moreira Soares(1), Franscismar Correa Marcelino‑Guimarães(1), Maurício Conrado Meyer(1) and Leila Maria Costamilan(2) (1)Embrapa Soja, Rodovia Carlos João Strass, s/no, Acesso Orlando Amaral, Distrito de Warta, Caixa Postal 231, CEP 86001‑970 Londrina, PR, Brazil. E‑mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (2)Embrapa Trigo, Rodovia BR‑285, Km 294, Caixa Postal 3081, CEP 99050‑970 Passo Fundo, RS, Brazil. E‑mail: [email protected] Abstract – Asian soybean rust, caused by the fungus Phakopsora pachyrhizi, is the most severe disease of the crop and can cause yield losses of up to 90%. The disease was first reported in Brazil in 2001. Epidemics of the disease are common in the country, where the fungus can survive year‑round. Regulatory measures to reduce the inoculum between seasons and avoid late‑season soybean have been adopted to manage the disease. Disease control has relied mainly on chemical control, but a lower sensibility of the fungus to fungicides has been reported in Brazil. Major‑resistance genes have been mapped and incorporated into the cultivars. With the reduced efficacy of the fungicides, the adoption of integrated measures to control the disease will be important for the sustainability of the crop. This review presents the main changes in the soybean crop system caused by the introduction of the fungus in Brazil, the current management strategies adopted to avoid losses, and the new trends that, together with biotechnological strategies, can improve management in the future. -

Soybean Rust Phakopsora Pachyrhizi and P

NationalNational PestPest AlertAlert Soybean Rust Phakopsora pachyrhizi and P. meibomiae Distribution and Transmission Two fungal species, Phakopsora pachyrhizi and P. meibomiae, cause soybean rust and are spread primarily by windborne spores that can be transported over long distances. Asian soybean rust, P. pachyrhizi, the more aggressive of the two species, was first reported in Japan in 1903 and was confined to the Eastern Hemisphere until its presence was documented in Hawaii in 1994. Currently, dis- tribution of P. pachyrhizi includes Africa, Asia, Australia, Hawaii, and South America. P. pachyrhizi’s rapid spread and severe damage with yield losses from 10 to 80% have been reported in Argentina, Asia, Brazil, Paraguay, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. In November, 2004, the presence of P. pachyrhizi was confirmed in the continental United States. Seedborne transmission of the disease has not been documented, but there is some concern that seed lots may contain small amounts of infected plant debris capable of spreading the pathogen. To date, seed lots have not proven to be a pathway for the disease. Clouds of Soybean rust lesion types and characteristics of early symptoms of spores are released if infected plants are disturbed by wind or by in- soybean rust and bacterial pustule. dividuals walking through rust-infected areas. Individuals who are sampling for soybean rust may transport spores from one area to another on clothing. If clothing is exposed to spores, care should be Host Range taken to prevent the spread of soybean rust to uninfected locations. P. pachyrhizi is capable of infecting more than 90 species of legumes; however, the number of legumes infected in nature is un- known. -

Soybean Response to Rust and Sclerotinia Stem Rot Under Different Biotic and Abiotic Conditions

SOYBEAN RESPONSE TO RUST AND SCLEROTINIA STEM ROT UNDER DIFFERENT BIOTIC AND ABIOTIC CONDITIONS CHRISNA STEYN Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR In the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences Department of Plant Sciences (Plant Pathology) University of the Free State Bloemfontein South Africa Promoter: Prof. N.W. McLaren June 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ............................................................................................................... i DEDICATION .................................................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. iii GENERAL INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... iv References .............................................................................................................. viii CHAPTER 1 .................................................................................................................... 1 AN OVERVIEW OF SCLEROTINIA STEM ROT AND SOYBEAN RUST IN SOUTH AFRICA .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Soybean production statistics ........................................................................... -

Soybean Rust Fungicide Use Guidelines

University of Kentucky College of Agriculture Plant Pathology Extension PPFS-AG-S-23 Plant Pathology Fact Sheet Soybean Rust Fungicide Use Guidelines by Donald E. Hershman, Extension Plant Pathologist These Soybean Rust Fungicide Use Guidelines represent the collective wisdom of many soybean plant pathologists from across the country, but have been tailored for use in Kentucky. Effective use of fungicides to control soybean rust is not very complicated. The whole idea is to wait to spray until the soybean rust risk is at least moderate, and make a fungicide application before significant infection has occurred. This means applying fungicides when plant pathologists in and around Kentucky are Soybean RuSt leSionS on the uppeR leaf SuRface and “sounding the alarm,” but before symptoms RuSt puStuleS on the undeRSide of the leaf (inSet) are evident. Many soybean producers in the deep South have been using fungicides to control soybean rust since 2005 with recent soybean rust risk status for the state. considerable success. I believe we will have Follow soybean rust spread in the U.S. by the same experience if it ever becomes going to http://www.sbrusa.net. necessary to apply fungicides for soybean rust in Kentucky. Note: Fungicide labels are legal documents and take priority over For additional information on soybean rust anything said in these guidelines. and fungicides labeled for soybean rust Be sure to read and follow ALL label control, visit the University of Kentucky instructions very closely. These Department of Plant Pathology website at guidelines are not intended to endorse http://www.uky.edu/SoybeanRust. Call the one product or class of products over Kentucky Soybean Promotion Board Hotline another. -

Asian Soybean Rust

Agriculture and Natural Resources Asian Soybean Rust Cliff Coker Introduction Since 1902, P. pachyrhizi has Associate Professor become a problem in various parts of Asian soybean rust is a serious Asia and Australasia. Kim Hurst disease threat to Arkansas and U.S. During the 1990s, the disease was Program Associate soybean production. On November 10, 2004, the disease was confirmed in reported in Africa, spreading to two soybean fields in Louisiana and various soybean-producing countries Terry Kirkpatrick shortly thereafter in Mississippi, there. Professor Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas, Missouri, South Carolina and In 2000-2001, P. pachyrhizi was Tennessee. The disease was found on John Rupe detected in Paraguay, South America, soybean plants that remained green and confirmed in Brazil and Professor very late in the season due to various Argentina in 2002 and Bolivia in factors. It was also noted on kudzu in 2003. It has caused major problems in Florida. All available evidence Chris Tingle these countries since its introduction. suggests that the disease was Extension Agronomist - introduced by windborne spores Soybeans carried from the northern edge of In 2004, the disease was South America to the southern U.S. by confirmed in Colombia, South Mark Trent Hurricane Ivan in September. On America, north of the equator, making its introduction into the southern U.S. Program Associate February 23, 2005, Asian soybean rust was confirmed as surviving on kudzu imminent – and this later occurred in in Pasco County, Florida, indicating September via Hurricane Ivan. successful overwintering. Reasons for the rapid geographic spread of Asian soybean rust from This fact sheet is intended to Asia to Africa and the Western provide information on biology, Hemisphere during the past decade identification and control of are not well understood. -

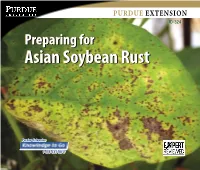

Preparing for Asian Soybean Rust, ID-324

PURDUE EXTENSION ID-324ID-324 PreparingPreparing forfor AsianAsian SoybeanSoybean RustRust Purdue Extension 1-888-EXT-INFO What is Asian soybean rust? 2 Asian soybean rust was first discovered in the continental United States in November 2004. This foliar disease is caused by the fungus Phakopsora pachyrhizi. Soybean rust is capable of destroying a soybean crop if it becomes established in a field early and weather conditions favor the spread of infection. The fungus is an obligate parasite, which means it can grow and reproduce only in living plant tissue. The fungus uses nutrients manufactured in soybean leaves to support its growth and reproduction. As a result, this drain on soybean plants can substantially reduce yields. A field heavily infected with Asian soybean rust in Mato Grosso, Brazil, February 2005. Photo by Shawn P. Conley, Purdue University. Purdue University. Conley, Photo by Shawn P. An ongoing concern As its name suggests, this fungus is native to Asia and was first detected in the Western hemisphere in Paraguay and southern Brazil in 2002, where it 3 spread and caused widespread crop damage. In late 2004, it was found for the first time in the continential United States in Louisiana and several other southern states. It is impossible to predict how often the disease will afflict soybean in Indiana, but based on our typical summer weather conditions, we could see it in 7 out of 10 years. Now that the fungus is in the United States, producers must deal with the possibility of soybean rust every year. This guide will help readers identify soybean rust symptoms, describe how the disease spreads, and how it can be controlled. -

U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Outlook Forum 2005

U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Outlook Forum 2005 February 25, 2005 INTEGRATION OF SOYBEAN RUST RESEARCH – USDA PERSPECTIVE A. Rick Bennett USDA – Agricultural Research Service Integration of Soybean Rust Research – USDA Perspective A. Rick Bennett USDA-Agricultural Research Service Phone: 301-504-6915 Email: [email protected] z What is soybean rust? z Why are we concerned? z Where does soybean rust occur? z What are the symptoms, biology and host range? z What are we doing about it? Soybean Rust z Caused by two species of fungi: ) Phakopsora pachyrhizi aka “Old World” isolate More aggressive pathogen ) Phakopsora meibomiae aka “New World” isolate Not as aggressive Soybean Rust - Phakospora pachyrhizi •Not seed borne •Readily spread by wind •Will not over winter in the midwest •Needs live host to survive/reproduce Why are we concerned about soybean rust? z The lack of resistance in U.S. commercial soybean cultivars and germplasm accessions. z The demonstrated ability of the pathogen to drastically reduce yield on soybean in countries where the disease occurs. z The ability of urediniospores of rust fungi, as a group, to quickly disseminate the pathogen, frequently over long distances. z Reports of the disease occurring in new locations. P.pachyrhizi P.meibomiae Recent Reports of Soybean Rust z Hawaii 1994 z Uganda 1996 z Zimbabwe 1998 z South Africa 2001 z Paraguay 2001 z Brazil 2002 z Argentina 2002 z Bolivia 2003 z Columbia 2004 z U.S. 2004 Country Yield loss (%) Australia 60-70 India 66 Indonesia 81 Japan 15-40 Philippines -

1 Epidemiology and Spread of Soybean Rust Glen L. Hartman1

Epidemiology and Spread of Soybean Rust Glen L. Hartman1, Monte R. Miles1, and Reid D. Frederick2 1USDA-ARS, National Soybean Research Center, Department of Crop Sciences, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 2FDWSRU, USDA-ARS, Frederick, MD Introduction Soybean rust is caused by two fungal species, Phakopsora meibomiae and P. pachyrhizi. The Asian soybean rust pathogen is known as P. pachyrhizi and is the species of greater concern since it is the more aggressive species and it has been identified in new geographical locations beyond Asia. Phakopsora meibomiae, the less virulent species, has only been found in the Western hemisphere, and it is not known to cause severe yield losses in soybean. The focus of almost all the literature (Hartman et al., 1992) and this paper is on P. pachyrhizi. Soybean rust is one of the major diseases of soybean in many Asian countries (Sinclair and Hartman, 1999) and now in Brazil, since its recent introduction in 2001 (Yorinori, 2003). Significant yield losses due to rust have been reported in most soybean-producing countries throughout Asia, where the disease is endemic. In some locations where rust is endemic, it may be a limiting factor in soybean production. The continental U.S. is one of the last major soybean production areas without soybean rust. Geographical Distribution P. pachyrhizi. The first report of soybean rust in the literature was from Japan in 1902. By 1934 the pathogen had been reported throughout much of Asia and Australia as well as on many of the islands between them (Fig. 1A). In tropical Southeast Asia, the disease is endemic and occurs throughout most of the year. -

Screening of Varieties Against Soybean Rust Caused by Phakopsora Pachyrhizi in Mid-Hills of Meghalaya

Indian Journal of Hill Farming Indian Journal of Hill Farming 25(1):17-20 Available online at www.kiran.nic.in Screening of Varieties Against Soybean Rust Caused by Phakopsora pachyrhizi in Mid-hills of Meghalaya P. BAISWAR1, N.TIAMEREN AO2, D.N. UPADHYAY2, S. CHANDRA1 ABSTRACT Screening trial was conducted for identification of resistant varieties/lines against soybean rust caused by Phakopsora pachyrhizi under natural epiphytotic conditions at Barapani, Meghalaya, India. Twenty three lines varieties/lines were included in the trial along with a susceptible check JS 335. Observations recorded were percent disease index, area under disease progress curve, apparent infection rate, defoliation and lesion type. Results revealed that only two lines NRC 80 and MAUS 417 were moderately susceptible. Lines TS 5, Himso 1676 and MAUS 282 were highly susceptible and all other lines were susceptible. No line or variety was in the moderately resistant or resistant category as all the lines exhibited Tan type lesions. Keywords: Soybean, Resistant, Tan type, RB type INTRODUCTION use of resistant varieties is considered to be the best and ecologically safe option. Keeping this in Soybean (Glycine max L. Merril) is an view, an experiment on screening of varieties for important crop in India and it has been declared as rust resistance was conducted for identifying a potential crop for northeast India including resistant lines/varieties. Meghalaya. It is used as oilseed, pulse and vegetable. It is also being considered as a component for increasing food security of rural MATERIALS AND METHODS households in northeast India. This crop also provides an added advantage of enhancing nitrogen Screening against soybean rust was conducted status of soils through nitrogen fixation (Jaiswal et using twenty three varieties/lines in Plant al. -

Surveillance for Soybean Rust in Florida

FDACS-P-01649 Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry Charles H. Bronson, Commissioner of Agriculture Surveillance for Soybean Rust in Florida Timothy S. Schubert and Wayne N. Dixon INTRODUCTION: Soybean rust is a very important exotic disease threatening commercial soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) production in the US. Though Florida grew only 11,000 acres of soybean (out of a total of approximately 73.4 million acres nationwide) in 2003, the Gulf Coast states are considered the likely zone of introduction for soybean rust into North America. Varietal screening done in quarantine by the USDA reveals that virtually all the existing commercially grown soybean cultivars are susceptible. Environmental conditions in the US are expected to be very favorable for rust development. Should the disease be introduced into the US, it would likely spread throughout the main US soybean production area in one season, with forecast losses exceeding $7.2 billion per year (Kuchler et al. 1984). In view of these facts, extensive surveys of various legume hosts for Asian soybean rust (Phakopsora pachyrhizi / P. meibomiae) are currently being done by the FDACS-DPI/CAPS, USDA-APHIS and UF-IFAS staff throughout Florida. The common name ‘soybean rust’ is applied to two rust diseases caused by two different pathogens: Phakopsora pachyrhizi, H. Sydow and Sydow, and P. meibomiae (Arthur) Arthur (Ono, et al 1992). Phakopsora pachyrhizi is by far the more aggressive and more destructive of the two pathogens. The two are impossible to distinguish in the field and under the microscope, hence the unusual situation of a single common name for diseases caused by two different pathogens. -

Weather-Based Assessment of Soybean Rust Threat to North America First Year Report to APHIS

Weather-Based Assessment of Soybean Rust Threat to North America First Year Report to APHIS 15 July 2004 Principal Investigators Scott A. Isard University of Illinois Champaign, IL Charlie Main (Principal Investigator), Thomas Keever, Roger Magarey North American Plant Disease Forecast Center NCSU Raleigh, NC Scott Redlin, CPHST/APHIS Raleigh, NC Joseph M. Russo ZedX, Inc. Bellefonte, PA Research Collaborators Stuart H. Gage Michigan State University East Lansing, MI Monte R. Miles & Glen L. Hartman USDA-ARS and the Department of Crop Sciences University of Illinois, Urbana, IL Executive Summary The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is preparing for the entry of soybean rust Phakopsora pachyrhizi in the conterminous United States. The belief is that aerial transport to the U.S. is a probable pathway for the initial entry of soybean rust and that the likelihood of aerial dispersal to our country will increase as the pathogen expands its range towards North America. The project, funded through a cooperative agreement between APHIS/USDA and North Carolina State University, brought together a group of soybean rust experts, aerobiologists, and information technologists to provide a highly visible, weather- based assessment of the soybean rust threat to North America. The project produced four deliverables and a report on schedule. (1) A web site through which APHIS is providing stakeholders with information on the aerial dispersal of soybean rust. (2) Maps of soybean rust source areas in Africa and South America. (3) Simulations of aerial soybean rust dispersal into South and North America using the HYSPLIT atmospheric transport model. (4) Simulations of aerial soybean rust dispersal into South and North America using the newly developed Integrated Aerobiology Model System framework.