Sea Turtle Consumption in the Maldives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

View Brochure

HIGH ENERGY DEEP IMMERSION Explore Group Adventures in the Maldives > DESTINATION THE COLLECTION PLAY EAT STAY RELAX CONNECT Beyond the Beaches The Maldives isn’t just for honeymooners. Or couples. Or beach-lovers. Or divers. Venture beyond the pearly whites and Tiffany blues of the world’s most aquatic nation and you’ll discover an archipelago that’s alive with culture and conservation, innovation and ingenuity. In a country of 1,192 low-lying islands strung across 90,000 square kilometres of the Indian Ocean, Four Seasons offers four distinctive properties that venture beyond the beaches to bring you more of the Maldives. Discover the Collection > DESTINATION THE COLLECTION PLAY EAT STAY RELAX CONNECT The Maldives Collection Discover the quintessential Maldivian quartet with Four Seasons Resort Four Seasons. Embark on a journey of wild UNESCO Four Seasons Resort Maldives at Kuda Huraa > Maldives at Landaa Giraavaru > discovery at Landaa Giraavaru; encounter a welcoming garden village at Kuda Huraa; explore undiscovered worlds Four Seasons Private Island Maldives at Voavah, Baa Atoll > above and below onboard Four Seasons Explorer; and play Four Seasons Explorer > with your own limitless potential at Voavah Private Island. DESTINATION THE COLLECTION PLAY EAT STAY RELAX CONNECT KUDA HURAA Feel the Magic Kuda Huraa isn’t a place, it’s a feeling: of warmth, comfort and naturalness. Charming and intimate, this enchanting garden island embraces guests with an almost familial devotion. A shared haven for water-lovers – from tiny turtles to surfing’s biggest names – Kuda Huraa is the ear-to-ear smile of catching your first wave, the spray-in-your-face joy of sailing alongside spinner dolphins, and the toes-in-the-sand rhythm of learning to beat a bodu beru drum. -

Table 2.3 : POPULATION by SEX and LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995

Table 2.3 : POPULATION BY SEX AND LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000 , 2006 AND 2014 1985 1990 1995 2000 2006 20144_/ Locality Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Republic 180,088 93,482 86,606 213,215 109,336 103,879 244,814 124,622 120,192 270,101 137,200 132,901 298,968 151,459 147,509 324,920 158,842 166,078 Male' 45,874 25,897 19,977 55,130 30,150 24,980 62,519 33,506 29,013 74,069 38,559 35,510 103,693 51,992 51,701 129,381 64,443 64,938 Atolls 134,214 67,585 66,629 158,085 79,186 78,899 182,295 91,116 91,179 196,032 98,641 97,391 195,275 99,467 95,808 195,539 94,399 101,140 North Thiladhunmathi (HA) 9,899 4,759 5,140 12,031 5,773 6,258 13,676 6,525 7,151 14,161 6,637 7,524 13,495 6,311 7,184 12,939 5,876 7,063 Thuraakunu 360 185 175 425 230 195 449 220 229 412 190 222 347 150 197 393 181 212 Uligamu 236 127 109 281 143 138 379 214 165 326 156 170 267 119 148 367 170 197 Berinmadhoo 103 52 51 108 45 63 146 84 62 124 55 69 0 0 0 - - - Hathifushi 141 73 68 176 89 87 199 100 99 150 74 76 101 53 48 - - - Mulhadhoo 205 107 98 250 134 116 303 151 152 264 112 152 172 84 88 220 102 118 Hoarafushi 1,650 814 836 1,995 984 1,011 2,098 1,005 1,093 2,221 1,044 1,177 2,204 1,051 1,153 1,726 814 912 Ihavandhoo 1,181 582 599 1,540 762 778 1,860 913 947 2,062 965 1,097 2,447 1,209 1,238 2,461 1,181 1,280 Kelaa 920 440 480 1,094 548 546 1,225 590 635 1,196 583 613 1,200 527 673 1,037 454 583 Vashafaru 365 186 179 410 181 229 477 205 272 -

MINISTRY of TOURISM Approved Opening Dates of Tourist

MINISTRY OF TOURISM REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES Approved Opening dates of Tourist Resorts, Yacht Marinas, Tourist Hotels, Tourist Vessels, Tourist Guesthouses, Transit Facilities and Foreign Vessels (Updated on 14th March 2021) TOURIST RESORTS Opening Date No. of No. of No. Facility Name Atoll Island Approved by Beds Rooms MOT Four Seasons Private Island 1 Baa Voavah 26 11 In operation Maldives at Voavah Four Seasons Resort Maldives at 2 Baa Landaa Giraavaru 244 116 In operation Landaa Giraavaru Alifu 3 Lily Beach Resort Huvahendhoo 250 125 In operation Dhaalu 4 Lux North Male' Atoll Kaafu Olhahali 158 79 In operation 5 Oblu By Atmosphere at Helengeli Kaafu Helengeli 236 116 In operation 6 Soneva Fushi Resort Baa Kunfunadhoo 237 124 In operation 7 Varu Island Resort Kaafu Madivaru 244 122 In operation Angsana Resort & Spa Maldives – 8 Dhaalu Velavaru 238 119 In operation Velavaru 9 Velaa Private Island Maldives Noonu Fushivelaavaru 134 67 In operation 10 Cocoon Maldives Lhaviyani Ookolhu Finolhu 302 151 15-Jul-20 Four Seasons Resort Maldives at 11 Kaafu Kuda Huraa 220 110 15-Jul-20 Kuda Huraa 12 Furaveri Island Resort & Spa Raa Furaveri 214 107 15-Jul-20 13 Grand Park Kodhipparu Maldives Kaafu Kodhipparu 250 125 15-Jul-20 Island E -GPS coordinates: 14 Hard Rock Hotel Maldives Kaafu Latitude 4°7'24.65."N 396 198 15-Jul-20 Longitude 73°28'20.46"E 15 Kudafushi Resort & Spa Raa Kudafushi 214 107 15-Jul-20 Oblu Select by Atmosphere at 16 Kaafu Akirifushi 288 114 15-Jul-20 Sangeli 17 Sun Siyam Olhuveli Maldives Kaafu Olhuveli 654 327 15-Jul-20 18 -

Coastal Adpatation Survey 2011

Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Maldives Integration of Climate Change Risks into Resilient Island Planning in the Maldives Project January 2011 Prepared by Dr. Ahmed Shaig Ministry of Housing and Environment and United Nations Development Programme Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Maldives Integration of Climate Change Risks into Resilient Island Planning in the Maldives Project Draft Final Report Prepared by Dr Ahmed Shaig Prepared for Ministry of Housing and Environment January 2011 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 COASTAL ADAPTATION CONCEPTS 2 3 METHODOLOGY 3 3.1 Assessment Framework 3 3.1.1 Identifying potential survey islands 3 3.1.2 Designing Survey Instruments 8 3.1.3 Pre-testing the survey instruments 8 3.1.4 Implementing the survey 9 3.1.5 Analyzing survey results 9 3.1.6 Preparing a draft report and compendium with illustrations of examples of ‘soft’ measures 9 4 ADAPTATION MEASURES – HARD ENGINEERING SOLUTIONS 10 4.1 Introduction 10 4.2 Historical Perspective 10 4.3 Types of Hard Engineering Adaptation Measures 11 4.3.1 Erosion Mitigation Measures 14 4.3.2 Island Access Infrastructure 35 4.3.3 Rainfall Flooding Mitigation Measures 37 4.3.4 Measures to reduce land shortage and coastal flooding 39 4.4 Perception towards hard engineering Solutions 39 4.4.1 Resort Islands 39 4.4.2 Inhabited Islands 40 5 ADAPTATION MEASURES – SOFT ENGINEERING SOLUTIONS 41 5.1 Introduction 41 5.2 Historical Perspective 41 5.3 Types of Soft Engineering Adaptation Measures 42 5.3.1 Beach Replenishment 42 5.3.2 Temporary -

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT for the Construction of a Slipway in Goidhoo Island, Shaviyani Atoll, Maldives

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT For the construction of a slipway in Goidhoo Island, Shaviyani Atoll, Maldives Photo: Water Solutions Proposed by: 3L Construction PVT.LTD Prepared by: Hassan Shah (EIA P02/2007) For Water Solutions Pvt. Ltd., Maldives May 2018 BLANK PAGE EIA For the construction of a slipway in Goidhoo Island, Shaviyani Atoll 1 Table of contents 1 Table of contents ...................................................................................................... 3 2 List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................ 7 3 Declaration of the consultants .................................................................................. 8 4 Proponents Commitment and Declaration ............................................................... 9 5 Non-Technical Summary ....................................................................................... 13 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 15 6.1 Structure of the EIA ........................................................................................... 15 6.2 Aims and Objectives of the EIA ........................................................................ 15 6.3 EIA Implementation .......................................................................................... 15 6.4 Rational for the formulation of alternatives ....................................................... 15 6.5 Terms of Reference........................................................................................... -

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF THE MALDIVES Public Disclosure Authorized TSUNAMI IMPACT AND RECOVERY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized JOINT NEEDS ASSESSMENT WORLD BANK - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK - UN SYSTEM ki QU0 --- i 1 I I i i i i I I I I I i Maldives Tsunami: Impact and Recovery. Joint Needs Assessment by World Bank-ADB-UN System Page 2 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DRMS Disaster Risk Management Strategy GDP Gross Domestic Product GoM The Government of Maldives IDP Internally displaced people IFC The International Finance Corporation IFRC International Federation of Red Cross IMF The International Monetary Fund JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation MEC Ministry of Environment and Construction MFAMR Ministry of Fisheries, Agriculture, and Marine Resources MOH Ministry of Health NDMC National Disaster Management Center NGO Non-Governmental Organization PCB Polychlorinated biphenyls Rf. Maldivian Rufiyaa SME Small and Medium Enterprises STELCO State Electricity Company Limited TRRF Tsunami Relief and Reconstruction Fund UN United Nations UNFPA The United Nations Population Fund UNICEF The United Nations Children's Fund WFP World Food Program ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a Joint Assessment Team from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the United Nations, and the World Bank. The report would not have been possible without the extensive contributions made by the Government and people of the Maldives. Many of the Government counterparts have been working round the clock since the tsunami struck and yet they were able and willing to provide their time to the Assessment team while also carrying out their regular work. It is difficult to name each and every person who contributed. -

Republic of Maldives: Preparing Outer Islands for Sustainable Energy Development

Initial Environmental Examination August 2014 Republic of Maldives: Preparing Outer Islands for Sustainable Energy Development Prepared by the Ministry of Environment and Energy, Government of Maldives for the Asian Development Bank This Initial Environmental Examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 March 2013) Currency Unit = Maldivian Ruffiyaa (MVR) MVR1.00 = US$ 0.065 US$1.00 = MVR 15.410 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank CFC - Chlorofluorocarbons DG - Diesel Generator EA - Executing Agency EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EPA - Environmental Protection Agency EMP - Environmental Management Plan EPC - Engineering, Procurement and Construction FENAKA - Fenaka Corporation Limited GoM - Government of Maldives GDP - Gross Domestic Product GFP - Grievance Focal Points GHG - Green House Gases GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GFP - Grievance Focal Point IA - Implementing Agency IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature MEE - Ministry of Environment and Energy MOF - Ministry of Finance PCBs - polychlorinated biphenyl PMC - Project Management Consultant PPTA - Project Preparatory Technical Assistance PV - photovoltaic REA - Rapid Environmental Assessment SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TA - Technical Assistance WHO - World Health Organization NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Madives ends on 31 December. -

Awarded Project List As of 30Th Jan 2020.Pdf

0 as of 30th January 2020 National Tender Ministry of Finance NATIONAL TENDER AWARDED PROJECTS Column1 Project Number Agency Project Name Island Awarded Party Awarded Amount in MVR Contract Duration Assembling of Kalhuvakaru Mosque and Completion of Landscape TES/2019/W-054 Completion of Landscape works AMAN Maldives Pvt Ltd MVR 2,967,867.86 120 Days Department of Heritage works TES/2019/W-103 Local Government Authority Construction of L. Isdhoo Council new Building L. Isdhoo UNI Engineering Pvt Ltd MVR 4,531,715.86 285 Days TES/2019/W-114 Local Government Authority Construction of Community Centre - Sh. Foakaidhoo Sh. Foakaidhoo L.F Construction Pvt Ltd MVR 5,219,890.50 365 Days TES/2019/W-108 Local Government Authority Construction of Council New Building at Ga. Kondey Ga. Kondey A Man Maldives pvt Ltd MVR 4,492,486.00 365 Days TES/2019/W-117 Local Government Authority Construction of Council Building at K.Hura K.Hura Afami Maldives Pvt Ltd MVR 5,176,923.60 300 Days TES/2019/W-116 Local Government Authority Construction of Council Building at Th. Madifushi Th. Madifushi Afami Maldives Pvt Ltd MVR 5,184,873.60 300 Days TES/2019/W-115 Local Government Authority Construction of Council Building at Lh.Naifaru Lh.Naifaru Nasa Link Pvt Ltd MVR 5,867,451.48 360 Days Safari Uniform fehumah PRISCO ah havaalukurumuge hu'dha ah 2019/1025/BC03/06 Maldives Correctional Service Male' Prison Cooperative Society (PRISCO) MVR 59,500.24 edhi TES/2019/G-014 Maldives Correctional Service Supply and Delivery Of Sea Transport Vessels K. -

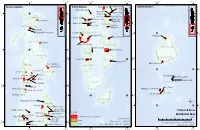

Protected Areas Distribution

73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E Northern Maldives Central Maldives Rasfari beyru Huraa Mangrove Area Southern Maldives Laamu Atoll Rasdhoo Madivaru Girifushi Thila Banana Reef Nassimo Thila 7°0'0"N 7°0'0"N Kuda Haa Lions Head Hans Hass Place; HP Reef Haa Alifu Atoll Mayaa Thila &% Kari beyru Thila Baarah Kulhi Emboodhoo Alifu Alifu Atoll Kanduolhi Orimas Thila 4°0'0"N Kaafu Atoll 4°0'0"N Haa Dhaalu Atoll Fish Head Guraidhoo &% Kanduolhi &% Keylakunu Neykurendhoo Mangrove Hurasdhoo Alifu Dhaalu Atoll 1°0'0"N 1°0'0"N Kudarah Thila Hithaadhoo Rangali Kandu Dhevana Kandu Shaviyani Atoll &% Farukolhu South Ari Atoll MPA Vaavu Atoll Filitheyo Kandu Gaafu Alifu Atoll Vattaru Kandu 6°0'0"N 6°0'0"N Faafu Atoll Noonu Atoll Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll Fushee Kandu Meemu Atoll 3°0'0"N Hakuraa Thila 3°0'0"N Kuredu Express Dhigulaabadhoo Raa Atoll &% Dhaalu Atoll &% Fushivaru Thila 0°0'0" 0°0'0" &% Bathala Region Anemone City &% Lhaviyani Atoll Mendhoo Region Angafaru Thoondi Area Dhandimagu Kilhi &% Maahuruvalhi &% &% &% &% Hanifaru Bandaara Kilhi Thaa Atoll Gnaviyani Atoll Baa Atoll Dhigali Haa &% 5°0'0"N Olhugiri 5°0'0"N Kan'di hera The Wreck of Corbin&% &% Hithadhoo Protected Area Goidhoo Koaru &% Seenu Atoll Mathifaru Huraa British Loyalty 2°0'0"N 2°0'0"N Laamu Atoll Makunudhoo channel &% Kaafu Atoll ¶ Rasfari beyru&% Huraa Mangrove Area 1°0'0"S 1°0'0"S &% Rasdhoo Madivaru &% Girifushi Thila &% Protected Areas &% Nassimo Thila &% Legend Kuda Haa &%Male' CityBanana Reef Kari beyru Thila &% &% Distribution Map Mayaa Thila Lions Head Hans Hass Place Protected Areas 2019 (Total 50 sites) 0 25 50 100 Km &% &% &% Sources: EPA 2019 Alifu Alifu Atoll Emboodhoo Islands Kanduolhi Map version Date: 30/06/2019 &% Orimas Thila Projection: Transverse Mercator (UTM Zone 43 N); 4°0'0"N &% 4°0'0"N Reefs Prepared by: Ministry of Environment, Maldives Fish Head &%Guraidhoo Kanduolhi Horizontal Datum: WGS84; 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E. -

Energy Supply and Demand

Technical Report Energy Supply and Demand Fund for Danish Consultancy Services Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources Maldives Project INT/99/R11 – 02 MDV 1180 April 2003 Submitted by: In co-operation with: GasCon Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report Map of Location Energy Consulting Network ApS * DTI * Tech-wise A/S * GasCon ApS Page 2 Date: 04-05-2004 File: C:\Documents and Settings\Morten Stobbe\Dokumenter\Energy Consulting Network\Løbende sager\1019-0303 Maldiverne, Renewable Energy\Rapporter\Hybrid system report\RE Maldives - Demand survey Report final.doc Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report List of Abbreviations Abbreviation Full Meaning CDM Clean Development Mechanism CEN European Standardisation Body CHP Combined Heat and Power CO2 Carbon Dioxide (one of the so-called “green house gases”) COP Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention of Climate Change DEA Danish Energy Authority DK Denmark ECN Energy Consulting Network elec Electricity EU European Union EUR Euro FCB Fluidised Bed Combustion GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green house gas (principally CO2) HFO Heavy Fuel Oil IPP Independent Power Producer JI Joint Implementation Mt Million ton Mtoe Million ton oil equivalents MCST Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology MOAA Ministry of Atoll Administration MFT Ministry of Finance and Treasury MPND Ministry of National Planning and Development NCM Nordic Council of Ministers NGO Non-governmental organization PIN Project Identification Note PPP Public Private Partnership PDD Project Development Document PSC Project Steering Committee QA Quality Assurance R&D Research and Development RES Renewable Energy Sources STO State Trade Organisation STELCO State Electric Company Ltd. -

Atoll Ecosystem-Based Conservation of Globally Significant Biological Diversity in the Maldives' Baa Atoll

Atoll Ecosystem-based Conservation of Globally Significant Biological Diversity in the Maldives’ Baa Atoll – GEF Project (MDV/02/G31) Terminal Evaluation Report 25th, December 2012 Elena Laura Ferretti Independent Consultant Acknowledgements The Consultant would like to express his appreciation and gratitude to all those who gave their time and provided invaluable information during the Terminal Evaluation of the AEC Project; their thoughts and opinions have informed the evaluation and contributed to its successful conclusion. Special thanks go to those in the local communities, local and national government who provided their time to the Consultant with great Maldivian hospitality. The Consultant is grateful for the arrangements put in place by the UNDP Country Office, Energy and Environment Programme. A special thank goes to Mihad Mohamed for its invaluable and effective support in all aspects related with logistics. The Consultant is also grateful to the staff of the PMU and in particular to Shibau for his very professional support in making appointments with key ministries and informants possible and for his opinions which greatly informed this evaluation. It should be noted that without Ismail from the PMU and all staff sitting in the Biosphere Reserve Office visits and interviews in Baa Atoll would not have been as smoother and effective as they have been. EXTERNAL Terminal Evaluation AEC project Baa Atoll, Maldives December 2012 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...............................................................................................................................