Backup of Livelihoods Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

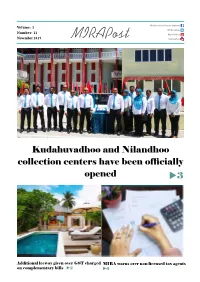

Kudahuvadhoo and Nilandhoo Collection Centers Have Been Officially Opened 3

Maldives Inland Revenue Authority Volume: 5 MIRAmaldives Number: 11 Mira Maldives November 2017 MIRAPost miramaldives Kudahuvadhoo and Nilandhoo MIRAcollection collects centers a record have MVR been 2.2 billion officially2 opened u3 MIRA’s teams to visit atolls to assist If annual income is over MVR 20 million, taxpayers in preparing financial statements GST returns must be filed online 11 and BPT Return 3 Additional leeway given over GST charged MIRA warns over non-licensed tax agents on complementary bills u2 u6 2 MIRAPost November 2017 MIRA October collection totals to 983.5 million Mariyam Juwairiyya date for payment of this fee was during October. Senior Tax Officer, Policy, Planning and Statistics Including the revenue of October, MIRA’s revenue collections add up to an aggregate of MVR 12.89 During October 2017, MIRA collected MVR billion so far. 983.5 million, including 38.1 million in US dollar. Other revenue types that contributed a This is a 10.7% rise compared to that of October significant share in October’s collection includes 2016 and a 4% rise in the expected revenue. GST (MVR 539.6 million), BPT (MVR 78.5 This increase was mainly contributed by Tourism million), Green Tax (MVR 53.9 million) and Land Rent (MVR 128.5 million), as the due Airport Service Charge (MVR 45.5 million). Additional leeway given over GST charged on complementary bills services provided free of charge to directors, employees Fathimath Amaanee Khalid and related parties, as specified under section 54 of Senior Tax Officer, Policy, Technical Service the GST Regulation, are not subject to GST for a period of 72 hours. -

Full Name Designation Group Ahmed Adhuham CITY RAEES ADDU

Full Name Designation Group Ahmed Adhuham CITY RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Mohamed Nihad DHAAIRAA RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ahmed Minthaz SUVADEEV GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Mohamed Saeed DHAAIRAA NAAIB RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ali Fahmee Ahmed ADDU CITY COUNCILOR ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Aishath Hasyna DHONDHEENA GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ahmed Shahum Razy EQUATOR GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Fathimath Saeedha HAMA HAMA GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Mohamed Saeed HIVVARU GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Mariyam Agisa KORUM GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ibrahim Najeeb Ali MEEZAAN GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ahmed Naseer RIHIDHOO GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Zeeniya Safiyyu SHELL GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Abdulla Rasheed STEALING PARADISE GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Abdulla Rasheed THASAVVARU GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ibrahim Junaid YELLOW GOFI GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Hawwa Zahira ZENITH GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ahmed Xirar MATHI HAMA GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Imad Salih EVEREST GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY ABDULLA SHAREEF ANTI CORRUPTION GOFI ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY MOHAMED SAEED EKALAS MIKALAS GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY MOHAMED HYDER MATHI AVAH GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY AHMED SAEED AABAARU GOFI RAEES ADDU HITHADHOO DHEKUNU CONSTITUENCY Mohamed Nazeer NAVARANNA GOFI RAEES ADDU HITHADHOO DHEKUNU CONSTITUENCY Ibrahim Nazil DHAAIRAA RAEES ADDU HITHADHOO DHEKUNU -

Table 2.3 : POPULATION by SEX and LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995

Table 2.3 : POPULATION BY SEX AND LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000 , 2006 AND 2014 1985 1990 1995 2000 2006 20144_/ Locality Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Republic 180,088 93,482 86,606 213,215 109,336 103,879 244,814 124,622 120,192 270,101 137,200 132,901 298,968 151,459 147,509 324,920 158,842 166,078 Male' 45,874 25,897 19,977 55,130 30,150 24,980 62,519 33,506 29,013 74,069 38,559 35,510 103,693 51,992 51,701 129,381 64,443 64,938 Atolls 134,214 67,585 66,629 158,085 79,186 78,899 182,295 91,116 91,179 196,032 98,641 97,391 195,275 99,467 95,808 195,539 94,399 101,140 North Thiladhunmathi (HA) 9,899 4,759 5,140 12,031 5,773 6,258 13,676 6,525 7,151 14,161 6,637 7,524 13,495 6,311 7,184 12,939 5,876 7,063 Thuraakunu 360 185 175 425 230 195 449 220 229 412 190 222 347 150 197 393 181 212 Uligamu 236 127 109 281 143 138 379 214 165 326 156 170 267 119 148 367 170 197 Berinmadhoo 103 52 51 108 45 63 146 84 62 124 55 69 0 0 0 - - - Hathifushi 141 73 68 176 89 87 199 100 99 150 74 76 101 53 48 - - - Mulhadhoo 205 107 98 250 134 116 303 151 152 264 112 152 172 84 88 220 102 118 Hoarafushi 1,650 814 836 1,995 984 1,011 2,098 1,005 1,093 2,221 1,044 1,177 2,204 1,051 1,153 1,726 814 912 Ihavandhoo 1,181 582 599 1,540 762 778 1,860 913 947 2,062 965 1,097 2,447 1,209 1,238 2,461 1,181 1,280 Kelaa 920 440 480 1,094 548 546 1,225 590 635 1,196 583 613 1,200 527 673 1,037 454 583 Vashafaru 365 186 179 410 181 229 477 205 272 -

Coastal Adpatation Survey 2011

Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Maldives Integration of Climate Change Risks into Resilient Island Planning in the Maldives Project January 2011 Prepared by Dr. Ahmed Shaig Ministry of Housing and Environment and United Nations Development Programme Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Maldives Integration of Climate Change Risks into Resilient Island Planning in the Maldives Project Draft Final Report Prepared by Dr Ahmed Shaig Prepared for Ministry of Housing and Environment January 2011 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 COASTAL ADAPTATION CONCEPTS 2 3 METHODOLOGY 3 3.1 Assessment Framework 3 3.1.1 Identifying potential survey islands 3 3.1.2 Designing Survey Instruments 8 3.1.3 Pre-testing the survey instruments 8 3.1.4 Implementing the survey 9 3.1.5 Analyzing survey results 9 3.1.6 Preparing a draft report and compendium with illustrations of examples of ‘soft’ measures 9 4 ADAPTATION MEASURES – HARD ENGINEERING SOLUTIONS 10 4.1 Introduction 10 4.2 Historical Perspective 10 4.3 Types of Hard Engineering Adaptation Measures 11 4.3.1 Erosion Mitigation Measures 14 4.3.2 Island Access Infrastructure 35 4.3.3 Rainfall Flooding Mitigation Measures 37 4.3.4 Measures to reduce land shortage and coastal flooding 39 4.4 Perception towards hard engineering Solutions 39 4.4.1 Resort Islands 39 4.4.2 Inhabited Islands 40 5 ADAPTATION MEASURES – SOFT ENGINEERING SOLUTIONS 41 5.1 Introduction 41 5.2 Historical Perspective 41 5.3 Types of Soft Engineering Adaptation Measures 42 5.3.1 Beach Replenishment 42 5.3.2 Temporary -

List of MOE Approved Non-Profit Public Schools in the Maldives

List of MOE approved non-profit public schools in the Maldives GS no Zone Atoll Island School Official Email GS78 North HA Kelaa Madhrasathul Sheikh Ibrahim - GS78 [email protected] GS39 North HA Utheem MadhrasathulGaazee Bandaarain Shaheed School Ali - GS39 [email protected] GS87 North HA Thakandhoo Thakurufuanu School - GS87 [email protected] GS85 North HA Filladhoo Madharusathul Sabaah - GS85 [email protected] GS08 North HA Dhidhdhoo Ha. Atoll Education Centre - GS08 [email protected] GS19 North HA Hoarafushi Ha. Atoll school - GS19 [email protected] GS79 North HA Ihavandhoo Ihavandhoo School - GS79 [email protected] GS76 North HA Baarah Baarashu School - GS76 [email protected] GS82 North HA Maarandhoo Maarandhoo School - GS82 [email protected] GS81 North HA Vashafaru Vasahfaru School - GS81 [email protected] GS84 North HA Molhadhoo Molhadhoo School - GS84 [email protected] GS83 North HA Muraidhoo Muraidhoo School - GS83 [email protected] GS86 North HA Thurakunu Thuraakunu School - GS86 [email protected] GS80 North HA Uligam Uligamu School - GS80 [email protected] GS72 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Afeefudin School - GS72 [email protected] GS53 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Jalaaludin school - GS53 [email protected] GS02 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Hdh.Atoll Education Centre - GS02 [email protected] GS20 North HDH Vaikaradhoo Hdh.Atoll School - GS20 [email protected] GS60 North HDH Hanimaadhoo Hanimaadhoo School - GS60 -

School Statistics 2013

SCHOOL STATISTICS 2013 MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Republic of Maldives FOREWORD Ministry of Education takes pleasure of presenting School Statistics 2013, to provide policymakers, educational planners, administrators, researchers and other stakeholders with suitable and effective statistical information. This publication is an integral part of the Educational Management Information System (EMIS) which is an essential source for quantitative educational data which reflects the improvement in educational policies and educational development in Maldives. We have been carefully and continuously collecting, analyzing, revising and updating the qualitative and quantitative data to make it as interpretive as possible, to ensure accuracy and reliability. We thank all who have contributed by providing the requested data to complete and make this publication a success. We thank the schools for their part in providing the data, the bodies within Ministry of Education for their tireless and valuable contribution and commitment in the preparation of the book, and also, the Department of National Planning (DNP) for providing us with the data on population. We hope that School Statistics 2013 will fulfill its objective of providing essential information to the education sector. SCHOOL STATISTICS 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Pages INTRODUCTION 1 SECTION 3: TEACHERS SECTION 1: ENROLMENT TRENDS & ANALYSIS Teachers by employment status by gender 46 Student enrolment 2001 to 2011 by provider 2 - 3 SECTION 4: STUDENT & POPULATION AT ISLAND LEVEL Transition rate -

Budget in Statistics 2015.Pdf

GOVERNMENT BUDGET IN STATISTICS FINANCIAL YEAR 2015 MINISTRY OF FINANCE & TREASURY MALE’ MALDIVES Table of Contents Executive Summary 01 Maldives Fiscal & Economic Outlook 03 The Budget System and Process 33 Budgetary Summary 2013-2017 39 Government Revenues 43 Glance at 2014 Budgeted & Revised Estimates 46 Proposed New Revenue Measures for 2015 47 Summary of Government Revenue (Tax & Non-Tax) 48 Government Total Receipts 2015 49 Government Revenue Details 2013 – 2017 55 Government Expenditures 61 Glance at Government Expenditures - 2014 64 Economic Classification of Government Expenditure, 2013 - 2017 65 Functional Classification of Government Expenditure, 2013 - 2017 70 Classification of Government Expenditure by AGAs, 2013 - 2017 73 Government Total Expenditures 2015 83 Project Loan Disbursements 2013-2017 97 Project Grant Disbursements 2013-2017 99 Public Sector Investment Program 101 PSIP 2014 (Domestic) Summary 103 PSIP Approved Budget Summary 2015 - 2017 104 PSIP Function Summary 2015 106 Review of the Budget in GFS Format, 2011-2017 109 Summary of Central Government Finance, 2011-2017 111 Central Government Revenue and Grants, 2011-2017 112 Economic Classification of Central Government Expenditure, 2011-2017 113 Functional Classification of Central Government Total Expenditure, 2011-2017 114 Functional Classification of Central Government Current & Capital Expenditure 115 Foreign Grants by Principal Donors, 2011-2017 116 Expenditure on Major Projects Financed by Loans, 2011-2017 117 Foreign Loans by Lending Agency, 2011-2017 118 Historical Data 119 Summary of Government Cash Inflow, 1998-2013 121 Summary of Government Cash Outflow, 1998-2013 122 Functional Classification of Government Expenditure, 1998-2013 123 1 Maldives Fiscal and Economic Outlook 2013-2017 1. -

South Asia Disaster Risk Management Programme

Synthesis Report on South Asian Region Disaster Risks – Final Report South Asia Disaster Risk Management Programme: Synthesis Report on SAR Countries Disaster Risks Synthesis Report on South Asian Region Disaster Risks – Final Report Table of Content PREFACE................................................................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.........................................................................................................................V LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................................VI ABBREVIATION USED............................................................................................................................X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................................................1 1.1 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 KEY FINDINGS ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 WAY FORWARD ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3.1 Additional analyses .................................................................................................................................. -

Maldives Education Response Plan

MALDIVES EDUCATION RESPONSE PLAN May 2020 For COVID-19 Ministry of Education Supported by with financial contribution from Maldives UNICEF, Maldives Global Partnership for Education Maldives Education Response Plan F O R C O V I D - 19 Ministry of Education Maldives May 2020 Supported by UNICEF, Maldives With financial contribution from Global Partnership for Education Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 3 PART A ........................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. Brief background to COVID-19 situation in the Maldives ....................................................... 6 3. Preliminary assessment of the potential impact of COVID-19 on the school education sector ...................................................................................................................................... 7 4 Preparedness and initial response of the sector .................................................................. 20 5 Key challenges in continuity of learning and reopening of schools ...................................... 23 6 Financial implications of COVID -19 on the school education sector ................................... 32 PART B ........................................................................................................................................ -

Island Scoping Study of Islands Announced for Bidding 2021

Island Scoping Study of Islands Announced for Bidding 2021 Islands Included: 1. Alidhuffarufinolhu, Haa Alif 2. Seedhihuraa / Seedhihuraa Veligan’du, Meemu 3. Olhufushi / Olhufushifinolhu, Thaa 4. Kaaddoo, Thaa 5. Kanimeedhoo, Thaa 6. Bodu Mun’gnafushi, Laamu 7. Kashidhoo, Laamu 8. Funadhooviligilla, Gaaf Alif 9. Maarehaa, Gaaf Alif 10. Fereytha Viligilla, Koderataa, Gaaf Dhaalu 11. Kan’dahalagalaa, Gaaf Dhaalu Island Scoping Study for Resort Development Volume II 4 Alidhuffarufinolhu, Haa Alif 4.1 Island Profile Alidhuffarufinolhu is a sand bank located on the eastern rim of Haa Alif Atoll, facing Gallandhoo . The sand bank is located at approximately 73° 6' 12.406" E, 6° 51' 41.501" N. Table below summarises information about Alidhuffarufinolhu. Table 4.1: Summary of basic information about Alidhuffarufinolhu Island Island Name Alidhuffarufinolhu Location 73° 6' 12.406" E, 6° 51' 41.501" N Island Area Within Vegetation Line - Within Low Tide Line 2.13 Ha Est. Mean tide (sq. m) 1.60 Ha Reef Area Overall area 423.87 Ha Within shallow reef 421.74 Ha Length ~ 380 m Width at the widest point ~ 82 m Distance to Malé International Airport ~ 299.20 km Distance to nearest domestic Airport ~ 14.00 km Distance to nearest resort ~ 5.70 km from Hideaway Beach & Spa Page|50 Island Scoping Study for Resort Development Volume II 4.2 Terrestrial Environment The following table summarizes key findings from the rapid assessment of the terrestrial environment associated with Alidhuffarufinolhu sandbank on 13th September 2013. Table 4.2: Terrestrial environment of Alidhuffarufinolhu Parameter Description Air Quality - Overall ambient air quality on the sandbank was good. -

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF THE MALDIVES Public Disclosure Authorized TSUNAMI IMPACT AND RECOVERY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized JOINT NEEDS ASSESSMENT WORLD BANK - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK - UN SYSTEM ki QU0 --- i 1 I I i i i i I I I I I i Maldives Tsunami: Impact and Recovery. Joint Needs Assessment by World Bank-ADB-UN System Page 2 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DRMS Disaster Risk Management Strategy GDP Gross Domestic Product GoM The Government of Maldives IDP Internally displaced people IFC The International Finance Corporation IFRC International Federation of Red Cross IMF The International Monetary Fund JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation MEC Ministry of Environment and Construction MFAMR Ministry of Fisheries, Agriculture, and Marine Resources MOH Ministry of Health NDMC National Disaster Management Center NGO Non-Governmental Organization PCB Polychlorinated biphenyls Rf. Maldivian Rufiyaa SME Small and Medium Enterprises STELCO State Electricity Company Limited TRRF Tsunami Relief and Reconstruction Fund UN United Nations UNFPA The United Nations Population Fund UNICEF The United Nations Children's Fund WFP World Food Program ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a Joint Assessment Team from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the United Nations, and the World Bank. The report would not have been possible without the extensive contributions made by the Government and people of the Maldives. Many of the Government counterparts have been working round the clock since the tsunami struck and yet they were able and willing to provide their time to the Assessment team while also carrying out their regular work. It is difficult to name each and every person who contributed.