Maldives Education Response Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Name Designation Group Ahmed Adhuham CITY RAEES ADDU

Full Name Designation Group Ahmed Adhuham CITY RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Mohamed Nihad DHAAIRAA RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ahmed Minthaz SUVADEEV GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Mohamed Saeed DHAAIRAA NAAIB RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ali Fahmee Ahmed ADDU CITY COUNCILOR ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Aishath Hasyna DHONDHEENA GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ahmed Shahum Razy EQUATOR GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Fathimath Saeedha HAMA HAMA GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Mohamed Saeed HIVVARU GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Mariyam Agisa KORUM GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ibrahim Najeeb Ali MEEZAAN GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ahmed Naseer RIHIDHOO GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Zeeniya Safiyyu SHELL GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Abdulla Rasheed STEALING PARADISE GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Abdulla Rasheed THASAVVARU GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ibrahim Junaid YELLOW GOFI GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Hawwa Zahira ZENITH GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Ahmed Xirar MATHI HAMA GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY Imad Salih EVEREST GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY ABDULLA SHAREEF ANTI CORRUPTION GOFI ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY MOHAMED SAEED EKALAS MIKALAS GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY MOHAMED HYDER MATHI AVAH GOFI RAEES ADDU FEYDHOO CONSTITUENCY AHMED SAEED AABAARU GOFI RAEES ADDU HITHADHOO DHEKUNU CONSTITUENCY Mohamed Nazeer NAVARANNA GOFI RAEES ADDU HITHADHOO DHEKUNU CONSTITUENCY Ibrahim Nazil DHAAIRAA RAEES ADDU HITHADHOO DHEKUNU -

List of MOE Approved Non-Profit Public Schools in the Maldives

List of MOE approved non-profit public schools in the Maldives GS no Zone Atoll Island School Official Email GS78 North HA Kelaa Madhrasathul Sheikh Ibrahim - GS78 [email protected] GS39 North HA Utheem MadhrasathulGaazee Bandaarain Shaheed School Ali - GS39 [email protected] GS87 North HA Thakandhoo Thakurufuanu School - GS87 [email protected] GS85 North HA Filladhoo Madharusathul Sabaah - GS85 [email protected] GS08 North HA Dhidhdhoo Ha. Atoll Education Centre - GS08 [email protected] GS19 North HA Hoarafushi Ha. Atoll school - GS19 [email protected] GS79 North HA Ihavandhoo Ihavandhoo School - GS79 [email protected] GS76 North HA Baarah Baarashu School - GS76 [email protected] GS82 North HA Maarandhoo Maarandhoo School - GS82 [email protected] GS81 North HA Vashafaru Vasahfaru School - GS81 [email protected] GS84 North HA Molhadhoo Molhadhoo School - GS84 [email protected] GS83 North HA Muraidhoo Muraidhoo School - GS83 [email protected] GS86 North HA Thurakunu Thuraakunu School - GS86 [email protected] GS80 North HA Uligam Uligamu School - GS80 [email protected] GS72 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Afeefudin School - GS72 [email protected] GS53 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Jalaaludin school - GS53 [email protected] GS02 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Hdh.Atoll Education Centre - GS02 [email protected] GS20 North HDH Vaikaradhoo Hdh.Atoll School - GS20 [email protected] GS60 North HDH Hanimaadhoo Hanimaadhoo School - GS60 -

Budget in Statistics 2015.Pdf

GOVERNMENT BUDGET IN STATISTICS FINANCIAL YEAR 2015 MINISTRY OF FINANCE & TREASURY MALE’ MALDIVES Table of Contents Executive Summary 01 Maldives Fiscal & Economic Outlook 03 The Budget System and Process 33 Budgetary Summary 2013-2017 39 Government Revenues 43 Glance at 2014 Budgeted & Revised Estimates 46 Proposed New Revenue Measures for 2015 47 Summary of Government Revenue (Tax & Non-Tax) 48 Government Total Receipts 2015 49 Government Revenue Details 2013 – 2017 55 Government Expenditures 61 Glance at Government Expenditures - 2014 64 Economic Classification of Government Expenditure, 2013 - 2017 65 Functional Classification of Government Expenditure, 2013 - 2017 70 Classification of Government Expenditure by AGAs, 2013 - 2017 73 Government Total Expenditures 2015 83 Project Loan Disbursements 2013-2017 97 Project Grant Disbursements 2013-2017 99 Public Sector Investment Program 101 PSIP 2014 (Domestic) Summary 103 PSIP Approved Budget Summary 2015 - 2017 104 PSIP Function Summary 2015 106 Review of the Budget in GFS Format, 2011-2017 109 Summary of Central Government Finance, 2011-2017 111 Central Government Revenue and Grants, 2011-2017 112 Economic Classification of Central Government Expenditure, 2011-2017 113 Functional Classification of Central Government Total Expenditure, 2011-2017 114 Functional Classification of Central Government Current & Capital Expenditure 115 Foreign Grants by Principal Donors, 2011-2017 116 Expenditure on Major Projects Financed by Loans, 2011-2017 117 Foreign Loans by Lending Agency, 2011-2017 118 Historical Data 119 Summary of Government Cash Inflow, 1998-2013 121 Summary of Government Cash Outflow, 1998-2013 122 Functional Classification of Government Expenditure, 1998-2013 123 1 Maldives Fiscal and Economic Outlook 2013-2017 1. -

Biosocioeconomic Assessment of the Effects of Fish Aggregating Devices in the Tuna Fishery in the Maldives

Bay of Bengal Programme BOBP/WP/95 Small-scale Fisherfolk Communities GCP/RAS/1 18/MUL Bioeconomics of Small-scale Fisheries RAS/91/006 Biosocioeconomic assessment of the effects of fish aggregating devices in the tuna fishery in the Maldives by Ali Naeem A Latheefa Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture Male, Maldives BAY OF BENGAL PROGRAMME Madras, India 1994 Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs) have proved very successful in the Maldives, where there is a countrywide FAD installation programme by the Ministry of Fish- eries and Agriculture (MOFA) underway. The main reason for the success of FADs in the Maldives is their applicability to the existing fisheries. With the motorization of the fishing fleet, the efficiency and range of operation of the fleet has increased. FADs help not only to reduce searching time and fuel costs, but they also consider- ably increase production. Although the aggregation of fish around FADs has been demonstrated successfully, and the merits of FAD-fishing proven, data on the cost-effectiveness of FADs are still lacking. MOFA, with the assistance of the Bay of Bengal Programme’s (BOBP) regional ‘Bioeconomics’ project (RAS/91/006), therefore, undertook to assess and quantify the impact of FADs in tuna fishing. The project installed two FADs in two separate areas in the Maldives and closely studied the biological, economic and sociological effects of them on the fisheries and on the island communities in the two areas. The effectiveness of the two FADs was measured by comparing data collected one year before and one year after their installation. The results of the study are presented in this paper. -

Vaguthee Inthikhab Committee

RASHU STEERING COMMITTEE 2020 Vaguthee Inthikhaabee Committee Haa Alif Atoll Island # Name Mobile No 1 Abdulla Rauf * 7781947 Vashafaru 2 Mahasin Mohamed 9642399 3 Moosa Haleem 7215549 1 Nazima Naeem 9736544 Hoarafushi 2 Moosa Mahir * 7845416 3 Hudha Abdhul Ganee 9949410 1 Aishath Suha * 7373916 Kela 2 Aishath Naziya 7568186 3 Aminath Thahuzeema 9136555 1 Fathimath Rahsha * 9942305 Utheemu 2 Fathimath Nuzuha 7688598 3 Aishath Ahmeema 7757203 1 Moosa Latheef * 7752000 Dhihdhoo 2 Aminath Rasheedha 7426560 3 Mariyam Saeedha 9762768 1 Moosa Naaf Ahmed 9567267 Filladhoo 2 Adam Nazeel * 9768148 3 Ahmed Faiz 9668070 1 Ahmed Athif * 9880528 Muraidhoo 2 Yoosuf Saeed 7869044 3 Aminath Baduriyya 9136005 1 Ali Shameem * 9999590 Baarah 2 Abdulla Afeef Ali 9502500 3 Aminath Nazma 7644034 1 Moosa Abdul Hafeez * 7980013 Ihavandhoo 2 Mohamed Shujau 7907031 3 Ahmed Shathir 7793159 1 Asma Ahmed * 7666651 Thuraakunu 2 Fariyaal Ibrahim 7626268 3 Ameena Abdul Rahmaan 7558293 1 Ahmed Arif * 7745638 Thakandhoo 2 Aimath Zeena 7875291 3 Rasheedha Mohamed 7903071 1 Aminath Nasira * 9142255 Maarandhoo 2 Fathimath Shiuna 9676760 3 Lamaah Hamid 9682363 1 Ibrahim Abul Rasheed * 7329399 Molhadhoo 2 Fathimath Azlifa 7818774 3 Ahmed Shiyam 7660669 * Committee Chair RASHU STEERING COMMITTEE 2020 Vaguthee Inthikhaabee Committee Noonu Atoll 1 Asma Abubakur 7887568 Magoodhoo 2 Majidha Hassan * 7892711 3 Agila Hussain 7941173 1 Shaheema Moosa 7586159 Fohdhoo 2 Ahmed Amjad * 7857473 3 Rasheedha Yoosuf 7896905 1 Nuzuhath Thahkhaan * 7535717 Henbadhoo 2 Mariyam Nahula 9572936 -

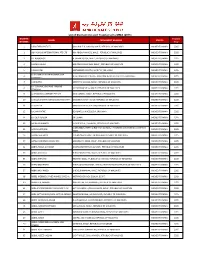

List of Dormant Account Transferred to MMA (2015) GAZETTE Transfer NAME PERMANENT ADDRESS STATUS NUMBER Year

List of Dormant Account Transferred to MMA (2015) GAZETTE Transfer NAME PERMANENT ADDRESS STATUS NUMBER Year 1 3 BROTHERS PVT.LTD. GROUND FLR, G.NISSA, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 2 A&A ABACUS INTERNATIONAL PTE LTD MA.ABIDHA MANZIL, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 3 A.1.BOOKSHOP H.SHAAN LODGE, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 4 A.ARUMUGUM MAJEEDHIYA SCHOOL, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 5 A.BHARATHI SEETHEEMOLI SOCTH, MARIPAY, SRI LANKA MOVED TO MMA 2015 A.DH OMADHOO RAHKURIARUVAA 6 A.DH OMADHOO OFFICE, ADH.OMADHOO, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 COMMITEE 7 A.EDWARD AMINIYYA SCHOOL, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 A.F.CONTRACTING AND TRADING 8 V.FINIHIYAA VILLA, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 COMPANY 9 A.I.TRADING COMPANY PVT LTD M.VIHAFARU, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 10 A.INAZ/S.SHARYF/AISH.SADNA/M.SHARYF M.SUNNY COAST, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 11 A.J.DESILVA MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 12 A.K.JAYARATNE KOHUWELA, NUGEGODA, SRI LANKA MOVED TO MMA 2015 14 A.V.DE.P.PERERA SRI LANKA MOVED TO MMA 2015 19 AALAA MOHAMED SOSUN VILLA, L.MAAVAH, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 C/OSUSEELA,JYOTHI GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL, HANUMAN JUNCTION,W.G.DISTRICT, 25 AARON MARNENI MOVED TO MMA 2015 INDIA 26 AASISH WALSALM C/O MEYNA SCHOOL, LH.NAIFARU, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 27 AAYAA MOHAMED JAMSHEED MA.BEACH HOUSE, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 32 ABBAS ABDUL GAYOOM NOORAANEE FEHI, R.ALIFUSHI, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 33 ABBAS ABDULLA H.HOLHIKOSHEEGE, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 35 ABBAS IBRAHIM IRUMATHEEGE, AA.BODUFULHADHOO, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 36 ABBAS MOHAMED DHUBUGASDHOSHUGE, HDH.KULHUDHUFFSUHI, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 37 ABBAS MOHAMED DHEVELIKINAARAA, MALE', REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES MOVED TO MMA 2015 38 ABDEL MOEMEN SAYED AHMED SAYED A. -

Annual Report 2016.Pdf

#surpriseparty #familytime #healthyliving #philipsairfryer #stohomeimprovement Airfryer Rapid air technology enables you to fry, bake, roast & grill the tastiest meals with less fat than using little or no oil! Attention This report comprises the annual report of state trading organization plc prepared in accordance with the companies act of the republic of maldives (10/96), listing rules of maldives stock exchange, the securities act of the republic of maldives (2/2006), securities continuing disclosure obligations of issuers regulation 2010 of capital market development authority and corporate governance code of capital market development authority requirements. Unless otherwise stated in this annual report, the terms ‘STO’, the ‘group’, ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’ refer to state trading organization plc and its subsidiaries, associates and joint ventures collectively. The term ‘company’ refers to STO and/or its subsidiaries. STO prepares its financial statements in accordance with international financial reporting standards (IFRS). References to a year in this report are, unless otherwise indicated, references to the Company’s financial year ending 31st december 2016. In this report, financial and statistical information is, unless otherwise indicated, stated on the basis of the Company’s financial year. Information has been updated to the most practical date. This annual report contains forward looking statements that are based on current expectations or beliefs, as well as assumptions about future events. These forward looking statements can be identified by the fact that they do not relate only to historical or current facts. Forward looking statements often use words such as ‘anticipate’, ‘target’, ‘expect’, ‘estimate’, ‘intend’, ‘plan’, ‘goal’, ‘believe’, ‘will’, ‘may’, ‘should’, ‘would’, ‘could’ or other words of similar meaning. -

Stat Book 2004

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2004 Student Enrolment in the Maldives (Gross) (1992 - 2004) 1 Enrolment Trends by Level (1999- 2004) 3 2004 Enrolment Trends by Level - Male’ and Atolls (2000 - 2004) 4 Enrolment by Level and Type 6 2004 Enrolment in Male' and Atolls by Grade and Gender 8 Enrolment in Male' and Atolls by Gender 10 2004 Enrolment Trends by Male' and Atolls (2002 - 2004) 12 Schools' Enrolments in Male' by Grade and Gender 14 2004 Schools' Enrolments in Haa Alifu Atoll by Grade and Gender 15 Schools' Enrolments in Haa Dhaalu Atoll by Grade and Gender 16 2004 Schools' Enrolments in Shaviyani Atoll by Grade and Gender 17 Schools' Enrolments in Noonu Atoll by Grade and Gender 18 2004 Schools' Enrolments in Raa Atoll by Grade and Gender 19 Schools' Enrolments in Baa Atoll by Grade and Gender 20 2004 Schools' Enrolments in Lhaviyani Atoll by Grade and Gender 21 Schools' Enrolments in Kaafu Atoll by Grade and Gender 22 2004 Schools' Enrolments in Alifu Alifu Atoll by Grade and Gender 23 Schools' Enrolments in Alifu Dhaalu Atoll by Grade and Gender 24 2004 Schools' Enrolments in Vaavu Atoll by Grade and Gender 25 Schools' Enrolments in Meemu Atoll by Grade and Gender 26 2004 Schools' Enrolments in Faafu Atoll by Grade and Gender 27 Schools' Enrolments in Dhaalu Atoll by Grade and Gender 28 20042004 Schools' Enrolments in Thaa Atoll by Grade and Gender 29 Schools' Enrolments in Laamu Atoll by Grade and Gender 30 2004 Schools' Enrolments in Gaafu Alifu Atoll by Grade and Gender 31 Schools' Enrolments in Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll by Grade and Gender -

Backup of Livelihoods Report

United Nations Development Programme 2005 - 2008 UNDP Tsunami Recovery Efforts in the Maldives RESTORATION OF LIVELIHOODS SHARING EXPERIENCES Table of Contents I Foreo w rd 1-2 Background 3-4 Livelihoods at a glance 5-6 Map 7-8 Donors & Partners 9-10 The Livelihoods Team 11-12 Profile: Agriculture 11 Story: The Young Agri-Shop Manager 13-14 Profile: Fisheries 13 Case Study: Naifaru Fish Market 15-16 Profile: Waste Management 15 Case Study: Waste Management in Baa Maalhos 17-18 Profile: Women's Livelihoods 17 Case Study: Hydroponics for Vilufushi Community 19-20 Profile: Small Grants Programme funded by South-South Grant Facility (SSGF) 19 Story: Broadband Internet to Hinnavaru Homes 21-22 Profile: Livelihood Support Activities - Micro Credit, Capacity Building & Decentralisation 23-24 Profile: Handicrafts Pilot Project 23 Story: A Woodworkers's Dream 25-28 Implementation Strategy 29-31 Primary Challenges 32 Case Study: Social Centre in Shaviyani Maroshi 33-36 Lessons Learnt & Best Practices 37-39 Conclusion & Way Forward FOREWORD Despite the overwhelming nature of the losses of the recovery intervention. December 2004 tsunami, many Maldivians are on the road to recovery; survivors have recommenced work, Our efforts to assist in the process of recovery for communities are close to completion, and several men and women determined to achieve self- have bounced back while others continue the steady sufficiency, has not been without obstacle. Human progress toward recovery. Through grants, loans and resource shortages, geographical barriers, the capacity building exercises, the United Nations construction boom and working with organizations Development Programme has worked to help with limited capacity in formal project management survivors of the tsunami restore their businesses and are just some of the challenges that had to be incomes, and find opportunities to remain outside addressed and overcome during our operations. -

Mdp Election 2012 . Results Entry Thuraakunu 130 A01-01 83 97.65 1

mdp election 2012 . results entry MEMBERS / CONSTITUENCY MEMBERS / PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE (1. MOHAMED NASHEED, ANNI) PROVINCE ATOLL NAME IN ENGLISH CONSTITUE ISLAND BALLOT BOX CODE ISLAND NCY YES % NO % Baathil % Total Vote Vote Lee % 48475 31798 98.43 269 0.83 238 0.74 32305 66.64 Thuraakunu 130 A01-01 83 97.65 1 1.18 1 1.18 85 65.38 A01 Hoarafushi 553 Uligamu 25 A01-02 11 100.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 11 44.00 Hoarafushi 398 A01-03 182 93.81 12 6.19 0 0.00 194 48.74 Molhadhoo 19 A02-01 1 100.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 1 5.26 A02 Ihavandhoo 573 Ihavandhoo 500 A02-02 373 97.39 4 1.04 6 1.57 383 76.60 Maarandhoo 54 A02-03 28 96.55 1 3.45 0 0.00 29 53.70 Thakandhoo 168 A03-01 89 98.89 1 1.11 0 0.00 90 53.57 HA Utheem 59 A03-02 42 97.67 1 2.33 0 0.00 43 72.88 A03 Baarashu 497 Muraidhoo 120 A03-03 86 100.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 86 71.67 Baarah 150 A03-04 116 100.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 116 77.33 A04 Dhiddhoo 516 Dhidhdhoo 516 A04-01 412 99.28 3 0.72 0 0.00 415 80.43 Vashafaru 86 A05-01 23 95.83 0 0.00 1 4.17 24 27.91 A05 Kelaa 544 Kelaa 311 A05-02 209 99.05 1 0.47 1 0.47 211 67.85 Filladhoo 147 A05-03 88 96.70 0 0.00 3 3.30 91 61.90 HA TOTAL 2683 1743 97.98 24 1.35 12 0.67 1779 66.31 Hanimaadhoo 216 B01-01 51 96.23 1 1.89 1 1.89 53 24.54 Faridhoo 8 B01-02 0 0.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 Finey 81 B01-03 56 100.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 56 69.14 B01 Hanimaadhoo 603 Naavaidhoo 116 B01-04 44 95.65 1 2.17 1 2.17 46 39.66 Nellaidhoo 173 B01-05 54 94.74 2 3.51 1 1.75 57 32.95 Hirimaradhoo 9 B01-06 0 0.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 Nolhivaranfaru 120 B02-01 65 100.00 0 0.00 0 0.00 65 54.17 Nolhivaram -

Improving Efficiency of Schooling in the Maldives: Is De-Shifting a Desirable Policy Direction?

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Improving Efficiency of Schooling in the Maldives: Is De-shifting a Desirable Policy Direction? A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Economics at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Aishath Sheryn 2011 COPYRIGHT Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ii Abstract Education, a vital component of human capital, is essential for the growth of nations. Developing countries, faced with limited resources and budget constraints, adopt strategies that they believe will improve access to education and at the same time reduce costs. This thesis explores the desirability of one such policy option, double-shift schooling, with respect to de-shifting, its reverse policy. Whether de-shifting is a desirable policy direction is assessed, based on other countries’ experiences, alternative strategies and the current education situation in the Maldives, a country presently under this transition. Some of these alternative strategies are explored for their effectiveness in improving the quality of education. In the case of the Maldives all schools were operating a double-shift system prior to 2009 and the government is now attempting to convert all schools to single-shift, by the end of 2013. -

Post-Tsunami Agricultural and Fisheries Rehabilitation Programme Project Performance Evaluation

Independent Office Independent Office of Evaluation of Evaluation Independent O ce of Evaluation Independent O ce of Evaluation International Fund for Agricultural Development International Fund for Agricultural Development Via Paolo di Dono, 44 - 00142 Rome, Italy Via Paolo di Dono, 44 - 00142 Rome, Italy Tel: +39 06 54591 - Fax: +39 06 5043463 Tel: +39 06 54591 - Fax: +39 06 5043463 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.ifad.org/evaluation www.ifad.org/evaluation www.twitter.com/IFADeval www.twitter.com/IFADeval Independent Office of Evaluation www.youtube.com/IFADevaluation www.youtube.com/IFADevaluation Independent Office Independent Office of Evaluation of Evaluation Independent O ce of Evaluation Independent O ce of Evaluation Republic of Maldives International Fund for Agricultural Development International Fund for Agricultural Development Post-Tsunami Agricultural and Fisheries Via Paolo di Dono, 44 - 00142 Rome, Italy Via Paolo di Dono, 44 - 00142 Rome, Italy Tel: +39 06 54591 - Fax: +39 06 5043463 Tel: +39 06 54591 - Fax: +39 06 5043463 Rehabilitation Programme E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.ifad.org/evaluation www.ifad.org/evaluation PROJECT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION www.twitter.com/IFADeval www.twitter.com/IFADeval www.youtube.com/IFADevaluation www.youtube.com/IFADevaluation Bureau indépendant Oficina de Evaluación de l’évaluation Independiente Bureau indépendant de l’évaluation Oficina de Evaluación Independiente Fonds international de développement agricole Fondo Internacional