2014-02-05 Duke CGGC WHO-UNCTAD Tobacco GVC Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Structure, Education and Cigarette Smoking of the Adults in China: a Double-Hurdle Model

Family Structure, Education and Cigarette Smoking of the * Adults in China: a Double-Hurdle Model Xiaohua Yu Ph.D. Candidate Agricultural, Environmental & Regional Economics and Demography Penn State University 308 Armsby Building University Park, PA 16802 Phone: +1.814.863.8248 Email: [email protected] David Abler Professor Agricultural, Environmental & Regional Economics and Demography Penn State University 207 Armsby Building University Park, PA 16802 Email: [email protected] * The first draft of this paper was presented in the seminar of the School of Finance at Renmin University of China in July 2007, and many thanks go to the seminar attendees, particularly to Professor G. Zhao of Economics of Renmin University of China, for their constructive advice. 1 Abstract : This paper suggests that cigarette smoking process can be divided into two steps: participation decision and consumption decision. Only a person decides to participate in cigarette smoking, can a positive number of cigarette consumption be observed. Following this logic, a double-hurdle statistic model is suggested for estimating the cigarette consumption, which also gives an approach to dealing with the problem of zero observations for non-smokers. Using 2004 China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), this study rejects the independence of the two decisions. The main finding is that family members can affect the participation decision of smoking but can not affect the consumption. In particular, those residing with parents, particularly with single parents, and those divorced are more likely to participate in smoking. And educational level can affect both participation decision and consumption decision, and the relation between education and cigarette addiction is more likely to be an inverted-U shape rather than a negative or positive linear relation. -

Marilyn E. Jackler Memorial Collection of Tobacco Advertisements AC1224

Marilyn E. Jackler Memorial Collection of Tobacco Advertisements AC1224 Date: 1971 Brand: Virginia Slims Manufacturer: Philip Morris Campaign: You’ve come a long way, baby. Theme: Targeting women, power, independence Key Phrase: We make Virginia Slims especially for women because they are biologically superior to men. Key Words: Virginia Slims, Long way, baby, cape, “W”, Superior, men women, superwomen Quote: “Women are more resistant to starvation, fatique, exposure, shock and illness than men are.” Comment: For more information contact the Archives Center at [email protected] or 202-633-3270 1 Marilyn E. Jackler Memorial Collection of Tobacco Advertisements AC1224 Date: 1989 Brand: Virginia Slims Manufacturer: Philip Morris Campaign: You’ve come a long way, baby., Menthol and Lights Menthol Theme: Targeting women, power, independence Key Phrase: We make Virginia Slims especially for women because they are biologically superior to men. Key Words: Virginia Slims Quote: You’ve come a long way, baby. Comment: The body of a women is no longer hidden behind big hoop skirts and layers. A women is now allowed to flaunt her healthy body. How long will she stay healthy if she is smoking? For more information contact the Archives Center at [email protected] or 202-633-3270 2 Marilyn E. Jackler Memorial Collection of Tobacco Advertisements AC1224 Date: 1991 Brand: Virginia Slims Manufacturer: Philip Morris Campaign: You’ve come a long way, baby., Menthol, Lights Theme: Targeting women Key Phrase: Virginia Slims remembers what most women’s bank accounts looked like in 1957. Key Words: Virginia Slims, Quote: Comment: Why in 1957 did women have to keep money in jars? They were not allowed to have a bank account separate from their husbands. -

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands As Either Premium Or Discount

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands as either Premium or Discount Category Name of Cigarette Brand Premium Accord, American Spirit, Barclay, Belair, Benson & Hedges, Camel, Capri, Carlton, Chesterfield, Davidoff, Du Maurier, Dunhill, Dunhill International, Eve, Kent, Kool, L&M, Lark, Lucky Strike, Marlboro, Max, Merit, Mild Seven, More, Nat Sherman, Newport, Now, Parliament, Players, Quest, Rothman’s, Salem, Sampoerna, Saratoga, Tareyton, True, Vantage, Virginia Slims, Winston, Raleigh, Business Club Full Flavor, Ronhill, Dreams Discount 24/7, 305, 1839, A1, Ace, Allstar, Allway Save, Alpine, American, American Diamond, American Hero, American Liberty, Arrow, Austin, Axis, Baileys, Bargain Buy, Baron, Basic, Beacon, Berkeley, Best Value, Black Hawk, Bonus Value, Boston, Bracar, Brand X, Brave, Brentwood, Bridgeport, Bronco, Bronson, Bucks, Buffalo, BV, Calon, Cambridge, Campton, Cannon, Cardinal, Carnival, Cavalier, Champion, Charter, Checkers, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Cimarron, Circle Z, Class A, Classic, Cobra, Complete, Corona, Courier, CT, Decade, Desert Gold, Desert Sun, Discount, Doral, Double Diamond, DTC, Durant, Eagle, Echo, Edgefield, Epic, Esquire, Euro, Exact, Exeter, First Choice, First Class, Focus, Fortuna, Galaxy Pro, Gauloises, Generals, Generic/Private Label, Geronimo, Gold Coast, Gold Crest, Golden Bay, Golden, Golden Beach, Golden Palace, GP, GPC, Grand, Grand Prix, G Smoke, GT Ones, Hava Club, HB, Heron, Highway, Hi-Val, Jacks, Jade, Kentucky Best, King Mountain, Kingsley, Kingston, Kingsport, Knife, Knights, -

INTERNATIONAL CIGARETTE PACKAGING STUDY Summary

INTERNATIONAL CIGARETTE PACKAGING STUDY Summary Technical Report June 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS RESEARCH TEAM ................................................................................................................... iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY PROTOCOL ........................................................................................................... 1 2.1 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................ 1 2.2 SAMPLE AND RECRUITMENT ................................................................................. 2 3.0 STUDY CONTENT ............................................................................................................. 3 3.1 STUDY 1: HEALTH WARNING MESSAGES ............................................................... 3 3.2 STUDY 2: CIGARETTE PACKAGING ......................................................................... 4 4.0 MEASURES...................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT .......................................................................... 6 4.2 QUESTIONNAIRE CONTENT ................................................................................... 6 5.0 SAMPLE INFORMATION ................................................................................................... 9 REFERENCES ........................................................................................................................ -

PMI Powerpoint Presentation

Investor Day – Asia Region Lausanne, June 23, 2010 Matteo Pellegrini President, Asia Region Philip Morris International Agenda ● Operating environment ● PMI strategic priorities in Asia ● Brand portfolio and innovations ● Key Asia markets: highlights ● Questions & Answers 2 Operating Environment 2009 • Population : 3.8 billion Korea Japan • Cigarette Volume: 3.4 trillion China Taiwan Cigarette Volume: Pakistan Hong Kong 1.2 trillion units (Excl. – China) Others 15% India Bangladesh Indonesia Thailand Philippines 22% Vietnam Bangladesh 6% Malaysia Pakistan Singapore 6% Vietnam Indonesia 7% Japan 20% Australia Philippines New Zealand 7% Korea 8% India Asia accounts for 56% of the world’s population 9% And 60% of the world’s cigarette volume… Note: Cigarette volumes reflect 2009 Source: Global Insights 3 GDP Per Capita in 15 Key Markets ($ 000) 50 43.9 39.9 36.4 30.4 USA US $ 46,300 European Union US $ 33,100 Asia Pacific US $ 4,000 17.2 16.5 7.0 Asia: $ 4.0 3.9 3.5 2.3 1.8 1.1 1.0 0.9 0.6 0 India China Japan Taiwan Vietnam Thailand Pakistan Malaysia Australia Indonesia Singapore Philippines Hong Kong Bangladesh South Korea Source: Global Insights 4 GDP Growth and Unemployment Rates (%) Japan (%) Australia 7 7 7 7 5.1 4.7 4.1 5.6 3.8 4.0 5.2 4.8 4.4 2.0 2.3 2.0 4.2 2008 2009 4.7 3.3 0 0 2.6 2006 2007 2010 F 2.4 (1.2) 1.3 (5.2) (7) (7) 0 0 GDP Growth Rate 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 F Unemployment Rate (%) Indonesia (%) Philippines 12 12 12 12 10.3 9.1 8.4 7.9 8.1 8.0 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.3 6.3 6.1 5.5 5.6 5.3 7.1 4.5 3.8 4.2 0.9 0 0 0 0 2006 2007 2008 -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

2009 Annual Report About PMI

2009 Annual Report About PMI Philip Morris International Inc. (PMI) is the leading inter- Contents 2 Highlights national tobacco company, with seven of the world’s top 3 Letter to Shareholders 15 brands, including Marlboro, the number one cigarette 6 2009 Business Highlights 8 Profitable Growth Through brand worldwide. PMI has more than 77,000 employees Innovation 16 Responsibility and its products are sold in approximately 160 coun- 17 Board of Directors/ tries. In 2009, the company held an estimated 15.4% Company Management 18 Financial Review share of the total international cigarette market outside 85 Comparison of Cumulative of the U.S., or 26.0% excluding the People’s Republic of Total Return 86 Reconciliation of China and the U.S. Non-GAAP Measures 88 Shareholder Information Highlights n Full-Year Reported Diluted Earnings per Share of $3.24 versus $3.31 in 2008 n Full-Year Reported Diluted Earnings per Share excluding currency of $3.77, up 13.9% n Full-Year Adjusted Diluted Earnings per Share of $3.29 versus $3.31 in 2008 n Full-Year Adjusted Diluted Earnings per Share excluding currency of $3.82, up 15.4% n During 2009, PMI repurchased 129.7 million shares of its common stock for $5.5 billion n PMI increased its regular quarterly dividend during 2009 by 7.4%, to an annualized rate of $2.32 per share n In July 2009, PMI announced an agreement to purchase the Colombian cigarette manufacturer, Productora Tabacalera de Colombia, Protabaco Ltda., for $452 million n In September 2009, PMI acquired Swedish Match South Africa (Proprietary) Limited, for approximately $256 million n In February 2010, PMI announced a new share repurchase program of $12 billion over 3 years n In February 2010, PMI announced the creation of a new company in the Philippines resulting from the unification of the business operations of Fortune Tobacco Corporation and Philip Morris Philippines Manufacturing Inc. -

Supplementary Files Supplemental Table 1: Tar And

Supplementary Files Supplemental Table 1: Tar and Ventilation Levels of Chinese Cigarette Brands in 2009 and 2012 2009 2012 Tar Tar UPC Brand Name (mg) Ventilated (mg) Ventilated 6901028000642 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028000987 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028001465 Shuangxi 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028001618 Shuang Xi 11 Yes 10 Yes 6901028002097 Cocopalm 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028002752 Cocopalm 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028011075 Jiatianxia 13 Yes 13 Yes 6901028015417 Zhenlong 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028024969 The X Catena Pride 8 Yes 8 No 6901028024990 Pride 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028025812 Pride 6 Yes 8 Yes 6901028028356 Tianxiaxiu 14 Yes 14 Yes 6901028036672 Huang Guoshu 13 Yes 13 Yes 6901028036795 Huang Guo Shu 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028037891 Huangguoshu 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028045483 Camellia 13 Yes 12 No 6901028048231 Hongtashan 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028055055 Honghe 12 Yes 13 Yes 6901028055086 Honghe 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028055208 Honghe 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028065078 Lan zhou 13 Yes 8 Yes 6901028065399 Lan zhou 13 Yes 8 Yes 6901028065580 Lan zhou 11 Yes 8 Yes 6901028071468 Zhongnanhai 5 Yes 5 Yes 6901028071499 Zhongnanhai 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028071529 Zhongnanhai 5 No 5 No 6901028071765 Zhongnanhai 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028072458 Beijing 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028072601 Zhongnanhai 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075763 Chunghwa 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075770 Chunghwa 13 Yes 12 Yes 6901028075831 Double Happiness 8 Yes 8 Yes 6901028075992 Double Happiness 12 Yes 12 Yes 6901028076333 Memphis Blue 9 Yes 9 Yes 6901028090902 Renmin Dahuitang Ben Xiang 10 No 10 Yes 6901028092944 Renmin Dahuitang 13 Yes 12 Yes -

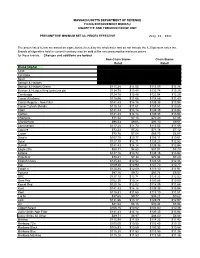

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Vaping and E-Cigarettes: Adding Fuel to the Coronavirus Fire?

Vaping and e-cigarettes: Adding fuel to the coronavirus fire? abcnews.go.com/Health/vaping-cigarettes-adding-fuel-coronavirus-fire/story By Dr. Chloë E. Nunneley 26 March 2020, 17:04 6 min read Vaping and e-cigarettes: Adding fuel to the coronavirus fire?Because vaping can cause dangerous lung and respiratory problems, experts say it makes sense that the habit could aggravate the symptoms of COVID-19. New data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week warns that young people may be more impacted by COVID-19 than was initially thought, with patients under the age of 45 comprising more than a third of all cases, and one in five of those patients requiring hospitalization. Although scientists still don’t have good data to explain exactly why some young people are getting very sick from the novel coronavirus, some experts are now saying that the popularity of e-cigarettes and vaping could be making a bad situation even worse. Approximately one in four teens in the United States vapes or smokes e-cigarettes, with the FDA declaring the teenage use of these products a nationwide epidemic and the CDC warning about a life-threatening vaping illness called EVALI, or “E-cigarette or Vaping- Associated Lung Injury.” Public health experts believe that conventional cigarette smokers are likely to have more serious illness if they become infected with COVID-19, according to the World Health Organization. Because vaping can also cause dangerous lung and respiratory problems, 1/4 experts say it makes sense that the habit could aggravate the symptoms of COVID-19, although they will need longer-term studies to know for sure. -

Seatca Packaging Design (25Feb2020)Web

No logos, colours, Pictorial health brand images or warnings used in promotional conjunction with information standardised packaging SMOKING CAUSES LUNG CANCER Pack surfaces in a standard colour Brand and product names in a standard colour and font 2020 Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance Packaging Design Analysis to Support Standardised Packaging in the ASEAN Authors: Tan Yen Lian and Yong Check Yoon Editorial Team: Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance Suggested citation: Tan YL. and Yong CY. (2020). Packaging Design Analysis to Support Standardised Packaging in the ASEAN, January 2020. Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA), Bangkok. Thailand. Published by: Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA) Thakolsuk Place, Room 2B, 115 Thoddamri Road, Dusit, Bangkok 10300 Thailand Telefax: +66 2 241 0082 Acknowledgment We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our country partners for their help in purchasing the cigarette packs from each country for the purpose of the study, which contributed to the development of this report. Disclaimer The information, ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reect the views of the funding organization, its sta, or its Board of Directors. While reasonable eorts have been made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented at the time of publication, SEATCA does not guarantee the completeness and accuracy of the information in this document and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. Any factual errors or omissions are unintentional. For any corrections, please contact SEATCA at [email protected]. © Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance 2020 This document is the intellectual property of SEATCA and its authors. -

Uk Standardised Packaging Consultation

UK STANDARDISED PACKAGING CONSULTATION RESPONSE OF BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO UK LIMITED 08 August 2012 Table of Contents Page ABOUT BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO UK LIMITED .............................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................2 1. QUESTION 1 ................................................................................................................. 10 1.1 Plain Packaging would not work and would have serious unintended consequences .................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Smoking prevalence is reducing without the need for risky additional measures ........................................................................................................... 11 1.3 The FCTC does not require Plain Packaging ..................................................... 11 1.4 Effective alternative measures ........................................................................... 12 2. QUESTION 2 ................................................................................................................. 15 3. QUESTION 3 ................................................................................................................. 16 3.1 The studies relied on in the PHRC Review are flawed and irrelevant ................. 17 3.2 Plain Packaging would not discourage young people from taking up smoking ... 20 3.3 Plain Packaging would not increase