E-Books and Other E-Content E-Books and Other E-Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Find Free, Reusable Content Online Rhode Island Library

Open Everything: How to find free, reusable content online Rhode Island Library Association Conference 2016, “Color Outside the Lines” Andrée Rathemacher • Julia Lovett • Angel Ferria University of Rhode Island Open Culture General Resources: Sites, Portals & Guides Digital Public Library of America — http://dp.la/ Aims to be a national digital library for the USA. Harvests metadata and content in all formats from other digital libraries and databases (HathiTrust, Internet Archive, state/consortium repositories, govt repositories etc. full partner list here http://dp.la/partners) Does not yet allow searching/filtering by rights information. Europeana — http://www.europeana.eu/portal/ Europe’s portal to cultural collections: “Explore 52,219,831 artworks, artefacts, books, videos and sounds from across Europe.” Can filter search results by reuse rights. Internet Archive — http://archive.org Founded in 1996. A “nonprofit library of millions of free books, movies, software, music, and more.” Searchable by Creative Commons license or Public Domain: See https://archive.org/about/faqs.php#1069 Open Culture — http://www.openculture.com/ Founded in 2006. Brings together free/open resources from around the web. Geared for a popular audience, with frequent blog posts and active social media presence. OpenGLAM Open Collections — http://openglam.org/opencollections/ A searchable index of open cultural her itage collections with freely reusable content. Shared Shelf Commons — http://www.sscommons.org Freely available images and oth er digital content from libraries, archives, and museums participating in Shared Shelf by Artstor. Copyright restrictions vary. Creative Commons Search — https://search.creativecommons.org/ Search CClicensed content from multiple sites such as Flickr, Google, and YouTube. -

Hathitrust Preferred Internet Archive Book Package Overview

HathiTrust Preferred Internet Archive Book Package Overview & Background As a by-product of the Internet Archive scanning process, a variety of different files and formats are available to everyone, everywhere. This differs from the Google output, which offers no file-level variations or options. However, this also means that files chosen for ingest into the HathiTrust repository must be carefully selected, with an eye towards both near-term and long-term utility. The process of selecting files that is described below attempted to balance the following important criteria: a baseline, cross-partner standard; functional consistency with the Google work products; a desire to keep the highest quality master images; a disinclination to discard useful information; and an attempt to minimize overall package size to reduce storage costs. Ingest into the HathiTrust repository will require pre-processing of the original file set described below in order to normalize files to an expected format. This normalization will allow HathiTrust processes to accommodate content from all partners. This process is currently in development and a link to the documentation of the process will be included here, once it is finalized. File Selection Criteria In the following section, the files selected for ingest into the HathiTrust repository are identified, along with a justification for why they were selected. Also listed are files that are available from the Internet Archive, but have not been selected. A description of each file can be found in the All Available Files & Characteristics section below. All files below are named using the Internet Archive identifier, preceding the underscore (ex. -

Overview of the INEX 2009 Book Track

Overview of the INEX 2009 Book Track Gabriella Kazai1, Antoine Doucet2, Marijn Koolen3, and Monica Landoni4 1 Microsoft Research, United Kingdom [email protected] 2 University of Caen, France [email protected] 3 University of Amsterdam, Netherlands [email protected] 4 University of Lugano [email protected] Abstract. The goal of the INEX 2009 Book Track is to evaluate ap- proaches for supporting users in reading, searching, and navigating the full texts of digitized books. The investigation is focused around four tasks: 1) the Book Retrieval task aims at comparing traditional and book-specific retrieval approaches, 2) the Focused Book Search task eval- uates focused retrieval approaches for searching books, 3) the Structure Extraction task tests automatic techniques for deriving structure from OCR and layout information, and 4) the Active Reading task aims to explore suitable user interfaces for eBooks enabling reading, annotation, review, and summary across multiple books. We report on the setup and the results of the track. 1 Introduction The INEX Book Track was launched in 2007, prompted by the availability of large collections of digitized books resulting from various mass-digitization projects [1], such as the Million Book project5 and the Google Books Library project6. The unprecedented scale of these efforts, the unique characteristics of the digitized material, as well as the unexplored possibilities of user interactions present exciting research challenges and opportunities, see e.g. [3]. The overall goal of the INEX Book Track is to promote inter-disciplinary research investigating techniques for supporting users in reading, searching, and navigating the full texts of digitized books, and to provide a forum for the exchange of research ideas and contributions. -

Electronic Reading Devices: Are They Hurting Or Helping the Print Publishing Industry?

Electronic Reading Devices: Are They Hurting or Helping the Print Publishing Industry? by Savannah Nikkole Wesley B.A., Middle Tennessee State University, 2014 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Mass Communications Department of Mass Communications In the Graduate School Middle Tennessee State University March, 2014 DEDICATION I’d like to dedicate this paper to my son Jeremiah Eden Wesley. Jeremiah you are my inspiration and the reason I keep going and working hard to better myself. I hope that gaining my Master’s degree not only opens doors in my life, but in yours also. It is my sincerest hope that every moment spent away from you in writing this thesis only shows you how sacrifice and dedication to improving yourself can give you a brighter future. I love you my son. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank Dr. Reineke for hours of invaluable assistance during the arduous research and writing portion of this paper. Additionally I sincerely appreciate all of my committee members for taking the time to give me your insights and feedback throughout this process. Finally, I’d like to thank Howard Books for three years of invaluable work and insight into many aspects of the publishing industry, which ultimately inspired the topic of this research thesis. iii Abstract With ever-evolving and emerging technology making an impact on today’s society, examining how this technology affects mass media is essential. This study attempts to delve into an emerging media - electronic reading devices - and research how they are changing the publishing industry by looking into the arenas of newspaper, magazine, and book publishing as well as at consumers of print media on a larger scale. -

The Internet Archive: an Interview with Brewster Kahle Brewster Kahle and Ana Parejo Vadillo

The Internet Archive: An Interview with Brewster Kahle Brewster Kahle and Ana Parejo Vadillo Rumour has it that one of the candidates for Librarian of Congress is Brewster Kahle, the founder and director of the non-profit digital library Internet Archive.1 That he may be considered for the post is a testament to Kahle’s commitment to mass digitization, the cornerstone of modern librarianship. A visionary of the digital preservation of knowledge and an outspo- ken advocate of the open access movement (the memorial for the Internet activist Aaron Swartz was held at the Internet Archive’s headquarters in San Francisco), Kahle has been part of the many ventures that have created our cyber age. At MIT, he was on the project team of Thinking Machines, a precursor of the World Wide Web. In 1989 he created WAIS (Wide Area Information Server), the first electronic publishing system, which was designed to search and make information available. He left Thinking Machines to focus on his newly founded company, WAIS, Inc., which was sold to AOL two years later for a reported $15 million. In 1996 he co- founded Alexa Internet, which was built on the principles of collecting Web traffic data and analysis.2 The company was named after the Library of Alexandria, the largest repository of knowledge in the ancient world, to highlight the potential of the Internet to become such a custodian. It was sold for c. $250 million in stock to Amazon, which uses it for data mining. Alongside Alexa Internet, in 1996 Kahle founded the Internet Archive to archive Web culture (Fig. -

Gen 102 Finding Full-Text Books Online

Finding Full-Text Books Online Internet Archive www.archive.org The Internet Archive is building a digital library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form, including video, audio, texts and the wayback machine. .Texts includes books and journals .Searches bibliographic information (see Open Library below for inside the book searching) .Displays text or image .Print from pdf (pdf may not be searchable) Open Library openlibrary.org Creating One web page for every book ever published. A project of Internet Archive .Books (Searches Internet Archive) .Displays text or image .Download or Print? o Searches bibliographic information, to identify books of interest Click on Subject to search by subject heading and can then keyword search within the heading (census, maps, Carey’s American pocket atlas) o Searching inside the book: openlibrary.org/search/inside Google Books books.google.com Google’s mission is to organize the world‘s information and make it universally accessible and useful. Books and Journals .Searches inside the book: use google search tools, use limiters in sidebar .Print from PDF—pdf downloaded is not searchable, must search in google books .Views: o Snippett o Preview o Download/pdf .Displays images (with some text in preview mode) .MORE .My Library .Order ebook, buy book, or get from a library Making of America quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moagrp/ Primary sources in American social history from the 19th century .Searches inside the book or document .Displays text or image or pdf .Can print one page at a time (best from pdf) .No download of complete book or article Family History Archive from Brigham Young University www.lib.byu.edu/fhc/index.php .search bib or inside book, pdf display, print, download Hathi Trust www.hathitrust.org A partnership of major research institutions and libraries to preserve and make books accessible. -

E-Books: Understanding the Basics June 2009 by Jane Lee, California Digital Library

E-books: Understanding the Basics June 2009 by Jane Lee, California Digital Library What exactly is an e-book anyway? Before we can talk about ebooks and the issues surrounding them, we must define what an e- book is. This is not as easy as one may think. Although e-books appear in headlines with regular frequency these days, there is still confusion about what exactly an e-book is that makes it difficult to focus on the real issues. For many people, especially in the last few years, an e-book is a handheld device whose main purpose is to look and act like a book. For others, an e-book is a book that one can read on one’s computer. And for a growing number of people, an e-book is something that you can read on your PDA, smartphone, iPod, etc. E-books made their first big splash on the market a decade ago, but they didn’t quite catch on with the general public. PDAs were taking a foothold, and companies began developing software that allowed people to read books on them. Subscription services for e-books – NetLibrary, for example – have been available to library patrons who have access to the required platform. The first dedicated, handheld electronic reading device, the Rocket ebook, made its appearance in 19981, but it wasn’t until the release of the Sony Reader and Amazon’s Kindle that e-book readers seemed commercially viable2. The arguments and questions about e-books – about their past, present, and future – that people formulate are shaped by how they define e-books for themselves. -

The Electronic Book As a Disruptive Technology." Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU History of the Book: Disrupting Society from Student Scholarship Tablet to Tablet 6-2015 Chapter 14 - The lecE tronic Book as a Disruptive Technology Janel Chandler Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/history_of_book Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Chandler, Janel. "The Electronic Book as a Disruptive Technology." Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet. 2015. CC BY-NC. This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of the Book: Disrupting Society from Tablet to Tablet by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 14 The Electronic Book as a Disruptive Technology -Janel Chandler- In 2011, the United States made $90.3 million in the ebook market1. The electronic book, or ebook, is a book that is read on a computer or other electronic device2. Ebooks were invented in 1971 with Michael Hart’s “Project Gutenberg,” and Electronic books like the Nook and the Kindle have later took the world by storm in revolutionized the reading market1. 1998 with the invention of the ereader by Peanut Press2,3. Ebooks were originally just digital copies of books that someone typed up and put on the Internet. This new technology was a disruptive innovation because it granted instant availability, allowed for easier storage, was more convenient, and completely revolutionized the book market1. -

Rethink Web Archiving! ! Helen Hockx-Yu, Director of Global Web Services Internet Archive

Rethink Web Archiving! ! Helen Hockx-Yu, Director of Global Web Services Internet Archive DPC Students Conference January 2016 About Me • Digital preservation / Web Archiving • Project / Programme / Operation/Service management • IT related • 2003-2007: Programme Manager, Digital Preservation and Shared Services, JISC • 2007-2008: Planets Project Manager, British Library • 2008 – 2015: Web Archiving Programme Manager & Head of Web Archiving, British Library • September 2015 – Present: Director of Global Web Services, Internet Archive 20 years of Web Archiving • Started by the Internet Archive in 1996 • Increased awareness • Legal issues much better understood • Growing community • 68 initiatives across 33 countries • 534 billions of web-archived files since 1996 (17 PB) • Scholarly use of web archives • Many challenges Internet Archive • A not-for-profit digital library founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle • Contains 24+PB of data and is growing • Digitised books, manuscripts and other texts • Movies & music • TV news archive: https://archive.org/details/tv • Software • Archived webpages • Over 2 million registered users https://archive.org/about/stats.php • Started web archiving in 1996. Wayback released in 2001 • Largest publicly available web archive in existence • 450+ Billion URLs, 100+ million websites • content in 40+ Languages • 600,000 visit / day • We collect a broad snapshot of the web every 60 days, +1billion ULRs/week • Also crawl wikipedia, news, RSS feeds, YouTube etc Archive-IT • Subscription service launched in February 2006 -

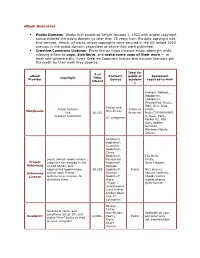

Ebook Resources Public Domain: Works First Published Before

eBook Resources Public Domain: Works first published before January 1, 1923 with proper copyright notice entered the public domain no later than 75 years from the date copyright was first secured. Hence, all works whose copyrights were secured in the US before 1923 are now in the public domain, regardless of where they were published. Creative Commons License: Every license helps creators retain copyright while allowing others to copy, distribute, and make some uses of their work — at least non-commercially. Every Creative Commons license also ensures licensors get the credit for their work they deserve. Ideal for # of eBook Content/ public or Equipment Copyright Titles Provider Genres academi required to view offered c Android, BeBook, Blackberry, eBookman, iPhone/iPod Touch, iPod, iRex, iLiad, Fiction and Public Domain Public or Kindle , Manybooks Non-Fiction and 26,021 Academic Nokia770/N800/N81 Creative Commons 0, Nook, Palm, 62 categories Pocket PC, PSP, Sony Reader, Symbian, Windows Mobile, Zaurus. Children's Bookshelf, Countries Bookshelf, Crime Bookshelf, The Nook, public domain books whose Periodicals Kindle, Project copyright has expired in the Bookshelf, Sony Ereader, Gutenberg United States, and Religion copyrighted books whose 30,000 Bookshelf, Public MP3 players, Gutenberg author gave Project Science gaming systems, License Gutenberg permission to Bookshelf, eBook readers, distribute them. Wars, mobile phones (Those 7 QiOO format. Subcategorie s are further broken down into 77 categories) Essays, Fiction, No area of terms and Non-Fiction, Readable on your conditions listed. Site just Readprint 8,000+ Poetry, Public computer only, states "Free" books to read Plays, not downloadable. on your computer. -

Die Neue Medialität Des Lesens: Ebooks Und Ebook- Reader“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die neue Medialität des Lesens: eBooks und eBook- Reader“ Verfasserin Daniela Drobna, Bakk.a phil Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im Februar 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 332 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Deutsche Philologie Betreuer: Assoz. Prof. Dr. Günther Stocker Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ............................................................................................................................... 1 2. Medientheoretische Einleitung ............................................................................................... 5 2.1. Definition Buch, eBook und eBook-Reader ...................................................................... 5 2.2. Medienevolution und Paradigmenwandel ....................................................................... 11 2.3. Medium und Medialität ................................................................................................... 18 2.4. Entwicklung von eBooks und eBook-Readern ............................................................... 22 2.5. Trends .............................................................................................................................. 26 3. Theorie der neuen Medialität des Lesens ............................................................................. 31 3.1. Paratexte .......................................................................................................................... 32 3.1.1. Typotopographie -

Are E-Books Effective Tools for Learning? Reading Speed and Comprehension: Ipad®I Vs

South African Journal of Education, Volume 35, Number 4, November 2015 1 Art. # 1202, 14 pages, doi: 10.15700/saje.v35n4a1202 Are e-books effective tools for learning? Reading speed and comprehension: iPad®i vs. paper Suzanne Sackstein, Linda Spark and Amy Jenkins Information Systems, Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa [email protected] Recently, electronic books (e-books) have become prevalent amongst the general population, as well as students, owing to their advantages over traditional books. In South Africa, a number of schools have integrated tablets into the classroom with the promise of replacing traditional books. In order to realise the potential of e-books and their associated devices within an academic context, where reading speed and comprehension are critical for academic performance and personal growth, the effectiveness of reading from a tablet screen should be evaluated. To achieve this objective, a quasi-experimental within- subjects design was employed in order to compare the reading speed and comprehension performance of 68 students. The results of this study indicate the majority of participants read faster on an iPad, which is in contrast to previous studies that have found reading from tablets to be slower. It was also found that comprehension scores did not differ significantly between the two media. For students, these results provide evidence that tablets and e-books are suitable tools for reading and learning, and therefore, can be used for academic work. For educators, e-books can be introduced without concern that reading performance and comprehension will be hindered.