Trade Marks Inter Partes Decision O/136/19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statista European Football Benchmark 2018 Questionnaire – July 2018

Statista European Football Benchmark 2018 Questionnaire – July 2018 How old are you? - _____ years Age, categorial - under 18 years - 18 - 24 years - 25 - 34 years - 35 - 44 years - 45 - 54 years - 55 - 64 years - 65 and older What is your gender? - female - male Where do you currently live? - East Midlands, England - South East, England - East of England - South West, England - London, England - Wales - North East, England - West Midlands, England - North West, England - Yorkshire and the Humber, England - Northern Ireland - I don't reside in England - Scotland And where is your place of birth? - East Midlands, England - South East, England - East of England - South West, England - London, England - Wales - North East, England - West Midlands, England - North West, England - Yorkshire and the Humber, England - Northern Ireland - My place of birth is not in England - Scotland Statista Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. +49 40 284 841-0 Fax +49 40 284 841-999 [email protected] www.statista.com Statista Survey - Questionnaire –17.07.2018 Screener Which of these topics are you interested in? - football - painting - DIY work - barbecue - cooking - quiz shows - rock music - environmental protection - none of the above Interest in clubs (1. League of the respective country) Which of the following Premier League clubs are you interested in (e.g. results, transfers, news)? - AFC Bournemouth - Huddersfield Town - Brighton & Hove Albion - Leicester City - Cardiff City - Manchester City - Crystal Palace - Manchester United - Arsenal F.C. - Newcastle United - Burnley F.C. - Stoke City - Chelsea F.C. - Swansea City - Everton F.C. - Tottenham Hotspur - Fulham F.C. - West Bromwich Albion - Liverpool F.C. -

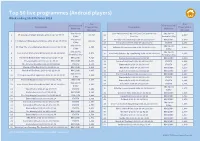

Top 50 Live Programmes (Android Players) Week Ending 23Rd October 2016

Top 50 live programmes (Android players) Week ending 23rd October 2016 Avg Avg Channel and Channel and Programme Programme Programme Programme Platform Platform Streams Streams Sky Sports Live United States Gp: Pit Lane Live 2016-10-23 Sky Sports 1 Pl: Liverpool V Man Utd Live 2016-10-17 19:00:00 17,760 26 2,437 1/Sky 19:00:00 Formula 1/Sky Sky Sports 27 Strictly Come Dancing 2016-10-22 18:38:00 BBC1/BBC 2,379 2 Pl: Chelsea V Manchester Utd Live 2016-10-23 15:30:48 11,119 1/Sky 28 Coronation Street 2016-10-21 19:32:02 ITV/ITV 2,333 Sky Sports Sky Sports 3 Pl: Man City v Southampton Live 2016-10-23 12:30:11 6,345 29 Gillette Soccer Saturday 2016-10-22 15:00:00 2,320 1/Sky 1/Sky Sky Sports Sky Sports 4 Live United States Grand Prix 2016-10-23 19:29:25 4,971 30 Live United States Gp: Qualifying 2016-10-22 18:00:00 2,313 Formula 1/Sky Formula 1/Sky 5 The Great British Bake Off 2016-10-19 20:00:27 BBC1/BBC 4,725 31 Eastenders 2016-10-20 19:29:25 BBC1/BBC 2,309 6 The Apprentice 2016-10-20 20:59:43 BBC1/BBC 4,394 32 Coronation Street 2016-10-21 20:29:54 ITV/ITV 2,288 7 The X Factor Results 2016-10-23 19:59:45 ITV/ITV 4,001 33 Emmerdale 2016-10-19 19:00:05 ITV/ITV 2,287 8 Match Of The Day 2016-10-22 22:21:00 BBC1/BBC 3,903 34 BBC News 2016-10-20 19:57:07 BBC1/BBC 2,220 9 Match Of The Day 2 2016-10-23 22:30:13 BBC1/BBC 3,895 35 Eastenders 2016-10-21 20:00:01 BBC1/BBC 2,217 Sky Sports 36 Ten O'clock News 2016-10-20 22:00:00 BBC1/BBC 2,213 10 Pl: Bournemouth V Spurs Live 2016-10-22 11:30:17 3,588 1/Sky 37 Emmerdale 2016-10-18 19:00:24 ITV/ITV 2,182 -

At My Table 12:00 Football Focus 13:00 BBC News

SATURDAY 9TH DECEMBER 06:00 Breakfast All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 10:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 09:25 Saturday Morning with James Martin 09:50 Black-ish 06:00 Forces News 11:30 Nigella: At My Table 11:20 Gino's Italian Coastal Escape 10:10 Made in Chelsea 06:30 The Forces Sports Show 12:00 Football Focus 11:45 The Hungry Sailors 11:05 The Real Housewives of Cheshire 07:00 Flying Through Time 13:00 BBC News 12:45 Thunderbirds Are Go 11:55 Funniest Falls, Fails & Flops 07:30 The Aviators 13:15 Snooker: UK Championship 2017 13:10 ITV News 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 08:00 Sea Power 16:30 Final Score 13:20 The X Factor: Finals 13:05 Shortlist 08:30 America's WWII 17:15 Len Goodman's Partners in Rhyme 15:00 Endeavour 13:10 Baby Daddy 09:00 America's WWII 17:45 BBC News 17:00 The Chase 13:35 Baby Daddy 09:30 America's WWII 17:55 BBC London News 18:00 Paul O'Grady: For the Love of Dogs 14:00 The Big Bang Theory 10:00 The Forces Sports Show 18:00 Pointless Celebrities 18:25 ITV News London 14:20 The Big Bang Theory 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 18:45 Strictly Come Dancing 18:35 ITV News 14:40 The Gadget Show 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 20:20 Michael McIntyre's Big Show 18:50 You've Been Framed! 15:30 Tamara's World 11:30 Hogan's Heroes Family entertainment with Michael McIntyre 19:15 Ninja Warrior UK 16:25 The Middle 12:00 Hogan's Heroes featuring music from pop rockers The Vamps and Ben Shephard, Rochelle Humes and Chris Kamara 16:45 Shortlist 12:30 Hogan's Heroes stand-up comedy from Jason Manford. -

World Cup 2006 Pack 2

Contents World Cup 2006 BBC presentation teams . 2 Schedule of games on the BBC . 3 BBCi – interactive TV and online . 4 BBC Radio Five Live . 8 Related programmes . 11 Behind the scenes . 15 Who’s who on the BBC TV team . .18 Who’s who on the BBC Radio Five Live team . 32 BBC World Cup 2006 BBC presentation teams BBC TV and radio presentation teams BBC TV on-air team Five Live on-air team Presenters: Presenters: Peter Allen (in alphabetical order) Steve Bunce Manish Bhasin Nicky Campbell Adrian Chiles Victoria Derbyshire Gary Lineker Kirsty Gallacher Ray Stubbs Simon Mayo Mark Pougatch Mark Saggers Match Commentators: Simon Brotherton Summarisers: John Motson Jimmy Armfield Guy Mowbray Terry Butcher Jonathan Pearce Dion Dublin Steve Wilson Kevin Gallacher Matt Holland Paul Jewell Co-commentators: Martin Jol Mark Bright Danny Mills Mark Lawrenson Graham Taylor Mick McCarthy Chris Waddle Gavin Peacock Commentators: Nigel Adderley Studio Analysts: Ian Brown Marcel Desailly Ali Bruce-Ball Lee Dixon Ian Dennis Alan Hansen Darren Fletcher Leonardo Alan Green Alan Shearer Mike Ingham Gordon Strachan Conor McNamara Ian Wright John Murray David Oates Mike Sewell Reporters: Football Correspondent: Garth Crooks Jonathan Legard Ivan Gaskell Celina Hinchcliffe Reporters: Damian Johnson Juliette Ferrington Rebecca Lowe Ricardo Setyon Matt Williams World Cup 2006 on the BBC 2 Schedule of games Schedule of games on the BBC ITV and the BBC have agreed plans for shared coverage of the World Cup finals in Germany, Live coverage of England’s Group matches -

World Cup 2006 Pack 2

The BBC team Who’s who on the BBC team Television presentation team commentator including the drive time Drive At 5 programme presenting the latest news and sport. Presenters During this period Manish’s highlights include reporting from Leicester Tigers’ last-minute Manish Bhasin – Presenter victory in the 2001 Rugby European Cup final (Leicester Tigers v Stade Francais) and again the following year at Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium (Leicester Tigers v Munster). Adrian Chiles – Presenter Manish Bhasin joined BBC Sport’s Football Focus team first as a reporter in early 2004 and then as a presenter. Prior to this Manish worked on ITV’s Central News programme and also presented Soccer Sunday. At Central News East Manish presented in-depth coverage of the region’s essential sport, including West Brom-mad Adrian Chiles was born in a comprehensive analysis of the financial crisis at Birmingham in 1967. Leicester City, and during his successful tenure Manish was nominated for Regional Sports After graduating with a degree in English Presenter or Commentator of the Year at the Literature from the University of London he Royal Television Society Sport Awards. attended a journalism course in Cardiff and worked as a sports reporter for, amongst Soccer Sunday was also nominated as best others, The News Of The World. Regional Sports Actuality Programme as Manish hosted Football League highlights of Adrian joined the BBC originally for three the best action from the region’s teams in a weeks’ work experience and by 1993 was regular magazine format. presenting Radio 4’s Financial World Tonight. In 1994 he started presenting Wake Up To Money Previously Manish Bhasin spent five years at BBC on the then newly formed Radio Five Live – a Radio Leicester as a sports presenter/ programme which still runs today. -

Made Outside London Programme Titles Register 2016

Made Outside London programme titles register 2016 Publication Date: 20 September 2017 About this document Section 286 of the Communications Act 2003 requires that Channels 3 and 5 each produce a suitable proportion, range and value of programmes outside of the M25. Channel 4 faces a similar obligation under Section 288. On 3 April 2017, Ofcom became the first external regulator of the BBC. Under the Charter and Agreement, Ofcom must set an operating licence for the BBC’s UK public services containing regulatory conditions. We are currently consulting on the proposed quotas as set out in the draft operating licence published on 29 March 2017. See https://www.ofcom.org.uk/consultations-and- statements/ofcom-and-the-bbc for further details. As our new BBC responsibilities did not start until April 2017 and this report is based on 2016 data, the BBC quotas reported on herein were set by the BBC Trust. This document sets out the titles of programmes that the BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5 certified were ‘Made outside of London’ (MOL) productions broadcast during 2016. The name of the production company responsible for the programme is also included where relevant. Wherever this column is empty the programme was produced in-house by the broadcaster. Further information from Ofcom on how it monitors regional production can be found at https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/87040/Regional-production-and-regional- programme-definitions.pdf. The three criteria under which a programme can qualify as MOL are: i) The production company must have a substantive business and production base in the UK outside the M25. -

55 Years of Match of the Day

55 YEARS OF MATCH OF THE DAY Now in its 55th year, Match of the Day returns to BBC 100 caps for his country and is well known to audiences available to watch earlier on BBC iPlayer from 7pm on One and BBC iPlayer on Saturday, August 10, to provide from his time at Everton and Millwall. Karen Carney is Sundays and MOTD2 from midnight also on Sunday. audiences with all of the highs and lows of the 2019- the second most capped England player of all time and 20 Premier League season. The most popular football has played for Arsenal, Chelsea and Birmingham where Starting in September, MOTDx is a brand new magazine programme on television reaches 7m viewers each she was the first woman to be inducted into their Hall of programme focusing on the lifestyle and culture of the weekend and Gary Lineker and the MOTD team will be on Fame. Premier League. Chelcee Grimes, Craig Mitch, Reece hand once again to provide expert insight and analysis Parkinson and Liv Cooke will join regular host Jermaine on one of the most entertaining leagues in world football. With over 50 major trophies between them, Jermaine Jenas and will dive into the world of music, fashion, Jenas, Phil Neville, Alex Scott, Martin Keown, Mark culture and football events. Taking over the reins from Des Lynam back in 1999, Gary Lawrenson, Danny Murphy, Dion Dublin, Garth Crooks, Lineker enters his 20th season as presenter of Match of Kevin Kilbane, Leon Osman and Jon Walters return to the Following on from the record-breaking audiences that the Day. -

MONDAY 14TH DECEMBER 06:00 Breakfast 09:15 Rip Off Britain

MONDAY 14TH DECEMBER All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 06:00 Good Morning Britain 09:50 The Secret Life of the Zoo 06:00 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 09:15 Rip Off Britain: Holidays 08:30 Lorraine 10:40 Inside the Tube: Going Underground 06:30 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 10:00 Homes Under the Hammer 09:25 The Jeremy Kyle Show 11:30 American Pickers: Best Of 07:00 The Aviators 11:00 Wanted Down Under 10:30 This Morning 12:20 Counting Cars 07:30 The Aviators 11:45 Caught Red Handed 12:30 Loose Women 12:45 The Mentalist 08:00 Hogan's Heroes 12:15 Bargain Hunt 13:30 ITV Lunchtime News 13:30 The Middle 08:30 Hogan's Heroes 13:00 BBC News at One 13:55 Itv News London 13:50 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 09:00 Hogan's Heroes 13:30 BBC London News 14:00 Judge Rinder's Crime Stories 14:15 Malcolm in the Middle 09:30 Hogan's Heroes 13:45 Doctors 15:00 Dickinson's Real Deal 14:40 Will and Grace 09:55 Hogan's Heroes 14:15 Father Brown 16:00 Tipping Point 15:05 Four in a Bed 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 15:00 I Escaped to the Country 17:00 The Chase 15:30 Extreme Cake Makers 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 15:45 The Farmers' Country Showdown 18:00 Itv News London 15:55 Don't Tell the Bride 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 16:30 Antiques Road Trip 18:30 ITV Evening News 16:45 Without a Trace 12:00 The Forces Sports Show 17:15 Pointless 19:00 Emmerdale 17:30 Forces News 12:30 Forces News 18:00 BBC News at Six 19:30 Coronation Street 18:00 Hollyoaks 13:00 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 18:30 BBC London News 20:00 The Martin Lewis Money Show 18:25 The Middle 13:30 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 19:00 The One Show 20:30 Coronation Street 18:50 Rich House, Poor House 14:00 The Aviators 19:30 Inside Out 21:00 Cold Feet 19:40 Escape to the Chateau 14:30 The Aviators Gareth Furby meets people who say they are 22:00 Itv News At Ten 20:30 Blue Bloods 15:00 Battle for the Skies forced to fight crime in their neighbourhoods. -

Sports Television Programming

Sports Television Programming: Content Selection, Strategies and Decision Making. A comparative study of the UK and Greek markets. Sotiria Tsoumita A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD Degree at the University of Stirling January 2013 Acknowledgements There are many people that I would like to thank for their help, support and contribution to this project starting from my two supervisors: Dr Richard Haynes for all his feedback, suggestions for literature, ideas and specialist knowledge in the UK market and Prof. Wray Vamplew for all the corrections, suggestions, for the enthusiasm he showed for the subject and for allowing me the freedom to follow my interests and make decisions. A special thanks because he was also involved in the project from the very first day that I submitted the idea to the university. I would also like to thank Prof. Raymond Boyle who acted as a second supervisor at the beginning of my PhD studies. This thesis would not have existed if it wasn’t for all the interviewees who kindly accepted to share their knowledge, experiences and opinions and responded to all my questions. Taking the interviews was the most enjoyable and rewarding part of the research. I would particularly like to thank those who helped me arrange new interviews: Henry Birtles for contacting Ben Nicholas, Vasilis Panagiotakis for arranging a number of interviews with colleagues in Greece and Gabrielle Marcotti who introduced me to Nicola Antognetti who helped me contact Andrea Radrizzani and Marc Rautenberg. Many thanks to friends and colleagues for keeping an eye on new developments in the UK and Greek television markets that could be of interest to my project. -

SATURDAY 3RD MARCH 06:00 Breakfast 10:00 Saturday Kitchen

SATURDAY 3RD MARCH All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 09:50 Black-ish 06:00 Forces News 10:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 09:25 ITV News 10:15 Playful Pups Make You Laugh Out Loud 06:30 The Forces Sports Show 11:30 Classic Mary Berry 09:30 Saturday Morning with James Marr 11:05 Sinbad 07:00 America's WWII 12:00 Football Focus 11:25 Dancing on Ice 11:55 Brooklyn Nine-Nine 07:30 Airwolf 13:00 BBC News Celebrity ice-skating contest, in which ten 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 08:30 Flying Through Time 13:15 Triathlon World Series: Abu Dhabi famous faces - all novices in the sport - take 13:05 Shortlist 09:00 Flying Through Time Highlights to the ice with professional partners in a bid 13:10 Malcolm in the Middle 09:30 Flying Through Time 14:45 Cycling: World Track Championships to win viewers' and keep their place in the 13:35 Malcolm in the Middle 10:00 The Forces Sports Show 16:30 Final Score competition. 14:00 Young & Hungry 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 17:10 A Question of Sport 13:25 ITV Lunchtime News 14:20 Young & Hungry 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 17:40 Celebrity Mastermind A thorough round-up of this lunchtime's main 14:45 Spa Wars 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 18:10 BBC News national and international news. 15:35 Don't Tell the Bride 12:00 Hogan's Heroes 18:20 BBC London News 13:30 ITV Racing: Live from Doncaster 16:25 The Middle 12:30 Hogan's Heroes 18:25 Pointless Celebrities 16:00 Tipping Point 16:50 Modern Family 13:00 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 19:15 All Together Now: The Final Fast paced quiz show sees four players take on 17:10 Shortlist 13:30 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 20:20 Casualty the familiar shove-penny style machine filled 17:15 Mannequin 14:00 Knight Rider 21:10 Troy Fall of a City with counters worth cash. -

Who Do English Football Commentators Think They Are?

Who do English football commentators think they are? Images: http://tvnewsroom.site/, uk.sports.yahoo.com, manutd.com, ianinthefuture.wordpress.com ‘It was a terrible clearance by the Japanese defender, lazy and casual’ (Sam Mataface, ITV, on Southampton vs Hapoel Beer-Sheba, 29/9/16) ‘What is ….trying there?’ (Guy Mowbray, BBC on West Ham vs Southampton, 25/9/16) ‘Hits Porto where it hurts…punishes Porto’ (David Stowell, ITV, on Leicester City vs Porto, 28/9/16) ‘Dispossessed by ..punish the error’ Clive Tyldesely, ITV on Celtic vs Manchester City, 28/9/16 I’ve had a feeling for some time that, despite no actual ability to play the game themselves, English football commentators can be cruel, judgemental know-it-all’s and that their Scottish equivalents are not. Sam Mataface’s comment above was the trigger for me to have a more scientific look at the performance of him and three other English commentators with a view to comparing them to a group of Scottish commentators. First, here’s a little context. You know this theory that we Scots are altogether more likeable people than our English neighbours, especially the Southern ones? I know, it’s just stupid. There are nice folk in East Anglia and nasty folk in East Renfrewshire. Indeed, wasn’t Jim Murphy the MP for East Renfrewshire? But, there is actually some hard evidence that, on the whole, ‘we’ are often nicer folk. Look at the recent spike in hate crime in England post Brexit and the lack of such in Scotland. See this in the Scotsman but from the London-based Mirror newspaper: ‘A Freedom of Information (FOI) request submitted by the Mirror revealed that, although tensions had boiled over in a number of places south of the Border - particularly in areas that had voted to leave the EU - Scotland was the only police force area in the UK where the number of recorded hate crimes fell.’ What about the vote for the Nasty Party (Tories), with their fondness for offshore accounts, hunting and shooting and hurting the poor and the disabled? In 2015, the Scottish Conservatives got 14.9% of the vote in Scotland. -

It's Sink Or Swim for Football's Minnows As the Deep Hosts the FA Cup

It’s sink or swim for football’s minnows as The Deep hosts the FA Cup Third Round draw Football’s coming home as FA Cup showpiece heads to Ebenezer’s birthplace Big fish and minnows have taken on a whole new meaning for the team at The Deep as the region’s leading tourist attraction prepares to host one of football’s great occasions. The arrival of the draw for the Third Round Proper of the FA Cup will complete a sporting hat-trick for the award-winning venue, which has already provided a spectacular backdrop for the Olympic Torch Relay and the Queen’s Baton Relay for the Commonwealth Games. England legend Alan Shearer will conduct the draw in partnership with Paul Adamson, a grassroots coach with the East Riding County FA, against the backdrop of a huge tank containing 2.5 million litres of water, 87 tonnes of salt and thousands of marine creatures. The event will be broadcast live on BBC Two in a special programme presented by Mark Chapman, the regular host of Match of the Day 2, and attended by Hull City Manager Steve Bruce and team captain Curtis Davies. Viewers can expect to catch a glimpse of such exotic marine life as sharks, rays, Green sawfish and the many other species which have helped The Deep win countless awards for tourism, business and sustainability. Freya Cross, Business and Corporate Manager at The Deep, said the draw has captured the imagination of fans who want to share in one of football’s great showpiece occasions.