Gifts That God Didn't Give

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vipers' Head Coach Resigns Meet

Vipers’ Head Coach Resigns Larry Brown resigns from his position due to medical issues Florence, SC – February 12, 2014 – The Pee Dee Vipers’ Head Coach, Larry Brown, has resigned from his position as a consequence of medical concerns and precautions. Brown and the Vipers took into consideration the long-term health of Brown and productivity of the team when making this decision. Brown does not feel that he can adequately provide the Vipers with the standard of coaching he is accustom to contributing and focus on improving his health at the same time. The entire Vipers Organization backs Brown in his decision and will continue to support him during his journey to good health. Andre Bovain has been named Head Coach. Bovain served as the Vipers’ Assistant Coach under Brown. NBA legend and Columbia, SC native, Xavier McDaniel will be one of the Vipers’ assistant coaches. Bryan Hergenroether will also join the Vipers’ coaching staff. The Vipers’ new coaching staff will leave much of what Brown has developed in place; plays and structure will be similar. Brown and Bovain worked closely to ensure that the coaching transition will be smooth and not dramatically impact the team’s winning style of play. Xavier McDaniel: • Played in college at Wichita State (1981-1985) • 4th overall in the 1985 NBA draft to the Seattle SuperSonics • Played 14 seasons in the NBA (1985-1998) • NBA All-Rookie First Team in 1986 • NBA All-Star in 1988 • Career Stats (NBA): Points – 13,606; Rebounds – 5,313; Assists – 1,775 • Played against names such as Magic Johnson, -

Remembrances and Thank Yous by Alan Cotler, W'72

Remembrances and Thank Yous By Alan Cotler, W’72, WG’74 When I told Mrs. Spitzer, my English teacher at Flushing High in Queens, I was going to Penn her eyes welled up and she said nothing. She just smiled. There were 1,100 kids in my graduating class. I was the only one going to an Ivy. And if I had not been recruited to play basketball I may have gone to Queens College. I was a student with academic friends and an athlete with jock friends. My idols were Bill Bradley and Mickey Mantle. My teams were the Yanks, the New York football Giants, the Rangers and the Knicks, and, 47 years later, they are still my teams. My older cousin Jill was the first in my immediate and extended family to go to college (Queens). I had received virtually no guidance about college and how life was about to change for me in Philadelphia. I was on my own. I wanted to get to campus a week before everyone. I wanted the best bed in 318 Magee in the Lower Quad. Steve Bilsky, one of Penn’s starting guards at the time who later was Penn’s AD for 25 years and who helped recruit me, had that room the year before, and said it was THE best room in the Quad --- a large room on the 3rd floor, looked out on the entire quad, you could see who was coming and going from every direction, and it had lots of light. It was the control tower of the Lower Quad. -

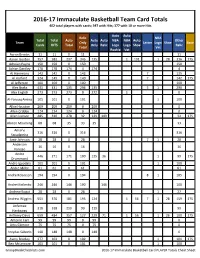

2016-17 Immaculate Basketball Player Checklist;

2016-17 Immaculate Basketball Team Card Totals 402 total players with cards; 397 with Hits; 377 with 10 or more Hits Auto Auto Relic NBA Total Total Auto Auto Auto NBA NBA Auto Other Team Only Letter Logo Shoe Base Cards HITS Total Only Relic Logo Logo Shoe Relic Total Vet Rookie Vet Aaron Brooks 11 11 0 11 11 Aaron Gordon 757 582 237 345 135 1 101 1 28 316 175 Adreian Payne 150 150 0 150 150 Adrian Dantley 178 178 174 4 174 4 AJ Hammons 142 142 0 142 7 135 Al Horford 324 149 0 149 7 142 175 Al Jefferson 100 100 0 100 100 Alec Burks 431 431 135 296 135 5 1 290 Alex English 273 273 273 0 272 1 0 Al-Farouq Aminu 101 101 0 101 1 100 Allan Houston 209 209 209 0 209 0 Allen Crabbe 124 124 124 0 124 0 Allen Iverson 485 310 278 32 129 149 32 175 Alonzo Mourning 68 68 35 33 35 33 Amar'e 316 316 0 316 316 Stoudemire Amir Johnson 28 28 0 28 7 1 20 Anderson 16 16 0 16 16 Varejao Andre 446 271 171 100 135 36 1 99 175 Drummond Andre Iguodala 101 101 0 101 1 100 Andre Miller 61 61 0 61 61 Andre Roberson 194 194 0 194 8 1 185 Andrei Kirilenko 246 246 146 100 146 100 Andrew Bogut 28 28 0 28 1 27 Andrew Wiggins 551 376 181 195 124 1 56 7 1 28 159 175 Anfernee 318 318 219 99 219 99 Hardaway Anthony Davis 659 484 357 127 229 71 1 56 1 26 100 175 Antoine Carr 99 99 99 0 99 0 Artis Gilmore 75 75 75 0 75 0 Arvydas Sabonis 148 148 148 0 148 0 Avery Bradley 277 102 0 102 1 101 175 Ben McLemore 101 101 0 101 1 100 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2016-17 Immaculate Basketball Card PLAYER Totals Cheat Sheet Auto Auto Relic NBA Total Total Auto Auto Auto NBA NBA Auto Other -

Deters Talks

^ V*''*IT* >t the weather Inside today Variable cloudiness today with chance of a few showers. Highs In mid Area news . 1-2B Family ....... ....6-7A to upper 60s. Partial clearing and^ool Classified . 6-lOB Gardening ........8A C o m ics............. IIB Obituaries .... 12A tonight. Low In upper '30s to mid «>s. Dear Abby___ IIB S p o rts.............3-5B Mostly sunny hut cool Friday with high Elditorial ...........4A 55-60. Chance of rain 30% today, 20% tonight, 10% Friday. National weather map on Page 7B. deters talks UNITED NATIONS (UPI) - One Cyrus Vance held with his counter the Palestinians at Geneva remained of the most intense bursts of parts from the Soviet Union and Mid unresolved — the Arabs still insist diplomatic activity on the Middle dle Eastern nations. the Palestinian Liberation Organiza East conflict has ended without an The Americans and Soviets issued tion go to Geneva and the Israelis agreement to reconvene the Geneva a joint statement this weekend still refuse to bargain with the PLO. peace talKs. recognizing for the first time the A joint U.S.-Israeli statement was High U.S. officials said Wednesday “rights” of the Palestinians and released after the Carter-Dayan the issue of who will represent the calling for their participation at meeting saying the two sides had St?’" Palestinians remains the principal Geneva, arousing speculation a made progess on resolving the obstacle to resuming the Geneva con breaKthrough was imminent. “remaining obstacles " to resuming a ference, and it will be weeKs before it Then President Carter and Vance Geneva conference. -

THE LITERACY CONNECTION - Opening Our Doors to the Dear Neighbor by Pat Andrews, CSJ

Online Update 6.1.7 May 18, 2021 A publication of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Boston Photo by: Ann Marie Garrity, CSJ THE LITERACY CONNECTION - Opening Our Doors to the Dear Neighbor by Pat Andrews, CSJ he Sisters of Saint Joseph and The Literacy Connection assisted in the fight against- COVID-19 by opening our doors to the neighborhood. For the third time, our neighborhood community arrived for their COVID-19 vaccine shots. On May 14, we Tsurprised when the van arrived from the Whittier Street Health Center, Dorchester, MA - a contingent of Army and Air Force medical personnel exited the vehicle! (Being an Air Force brat all my life, I saluted!) This group of soldiers belong to a medical unit stationed at Otis Air Base on Cape Cod that was formed to assist the Commonwealth in its battle against the virus. The Literacy Connection has been working with Heloisa Galvao, Director of the Brazilian Women's Group in Brighton, MA. Heloisa has been able to contact the medical staff needed and The Literacy Connection has been able to provide the space and protocals needed to follow all COVID-19 procedures. This is one of many examples of the commitment and collaboration among programs here in the Allston-Brighton Community. We are grateful to be an active member of this community. We can't do all this alone. I am exceedingly grateful to these pandemic angels who have graciously welcomed nervous older visitors, cranky children (placated with lollipops) and the younger generation. Thank you to Sisters Jo Perico, Rosemary Brennan, Carlotta Gilarde, Elizabeth Toomey, Kay Decker, Gail Donohue, Kathy Berube, Mary Rita Grady,Cathy Mozzicato as well as CSJ employee Chi Leung. -

Downtrodden Yet Determined: Exploring the History Of

DOWNTRODDEN YET DETERMINED: EXPLORING THE HISTORY OF BLACK MALES IN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL AND HOW THE PLAYERS ASSOCIATION ADDRESSES THEIR WELFARE A Dissertation by JUSTIN RYAN GARNER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, John N. Singer Committee Members, Natasha Brison Paul J. Batista Tommy J. Curry Head of Department, Melinda Sheffield-Moore May 2019 Major Subject: Kinesiology Copyright 2019 Justin R. Garner ABSTRACT Professional athletes are paid for their labor and it is often believed they have a weaker argument of exploitation. However, labor disputes in professional sports suggest athletes do not always receive fair compensation for their contributions to league and team success. Any professional athlete, regardless of their race, may claim to endure unjust wages relative to their fellow athlete peers, yet Black professional athletes’ history of exploitation inspires greater concerns. The purpose of this study was twofold: 1) to explore and trace the historical development of basketball in the United States (US) and the critical role Black males played in its growth and commercial development, and 2) to illuminate the perspectives and experiences of Black male professional basketball players concerning the role the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and National Basketball Retired Players Association (NBRPA), collectively considered as the Players Association for this study, played in their welfare and addressing issues of exploitation. While drawing from the conceptual framework of anti-colonial thought, an exploratory case study was employed in which in-depth interviews were conducted with a list of Black male professional basketball players who are members of the Players Association. -

Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs

2013-14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs 60 Atlanta Hawks 10 Al Horford Top-Notch Autographs Gold 60 Atlanta Hawks 5 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs 88 Atlanta Hawks 325 DeMarre Carroll Top-Notch Autographs Gold 88 Atlanta Hawks 25 Dennis Schroder Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 23 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys 25 Atlanta Hawks 199 Dennis Schroder Rookie Jumbo Jerseys Prime 25 Atlanta Hawks 25 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs 4 Atlanta Hawks 15 Jeff Teague Digs and Sigs Prime 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink 56 Atlanta Hawks 10 Jeff Teague Foundations Ink Gold 56 Atlanta Hawks 5 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs 1 Atlanta Hawks 35 Kevin Willis Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 1 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs 4 Atlanta Hawks 25 Kevin Willis Top-Notch Autographs Gold 4 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs 10 Atlanta Hawks 15 Kyle Korver Digs and Sigs Prime 10 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink 23 Atlanta Hawks 10 Kyle Korver Foundations Ink Gold 23 Atlanta Hawks 5 Pero Antic Main Exhibit Signatures Rookies 43 Atlanta Hawks 299 Spud Webb Main Exhibit Signatures 2 Atlanta Hawks 75 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs 3 Atlanta Hawks 199 Steve Smith Game Jerseys Autographs Prime 3 Atlanta Hawks 25 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs 31 Atlanta Hawks 325 Steve Smith Top-Notch Autographs Gold 31 Atlanta Hawks 25 groupbreakchecklists.com 13/14 Innovation Basketball Player Set Card # Team Print Run Bill Sharman Top-Notch Autographs -

Boston Celtics Game Notes

2020-21 Postseason Schedule/Results Boston Celtics (1-3) at Brooklyn Nets (3-1) Date Opponent Time/Results (ET) Record Postseason Game #5/Road GaMe #3 5/22 at Brooklyn L/93-104 0-1 5/25 at Brooklyn L/108-130 med0-2 Barclays Center 5/28 vs. Brooklyn W/125-119 1-2 Brooklyn, NY 5/30 vs. Brooklyn 7:00pm 6/1 at Brooklyn 7:30pm Tuesday, June 1, 2021, 7:30pm ET 6/3 vs. Brooklyn* TBD 6/5 at Brooklyn* TBD TV: TNT/NBC Sports Boston Radio: 98.5 The Sports Hub *if necessary PROBABLE STARTERS POS No. PLAYER HT WT G GS PPG RPG APG FG% MPG F 94 Evan Fournier 6’7 205 4 4 14.8 3.0 1.5 41.3 32.7 F 0 Jayson Tatum 6’8 210 4 4 30.3 5.0 4.5 41.7 36.0 C 13 Tristan Thompson 6’9 254 4 4 10.8 10.0 1.0 63.3 25.6 G 45 Romeo Langford 6’4 215 3 1 6.3 3.0 1.0 30.0 23.7 G 36 Marcus Smart 6’3 220 4 4 18.8 3.8 6.5 49.0 36.0 *height listed without shoes INJURY REPORT Player Injury Status Jaylen Brown Left Scapholunate Ligament Surgery Out Kemba Walker Left Knee Medial Bone Bruise Doubtful Robert Williams Left Ankle Sprain Doubtful INACTIVE LIST (PREVIOUS GAME) Player Jaylen Brown Kemba Walker Robert Williams POSTSEASON TEAM RECORDS Record Home Road Overtime Overall (1-3) (1-1) (0-2) (0-0) Atlantic (1-3) (1-0) (0-2) (0-0) Southeast (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) Central (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) (0-0) Eastern Conf. -

1980-89 NBA Finals

NBA FINALS 198 0 - 1 9 8 9 Detroit Pistons sweep Los Angeles Lakers 1 63-19 1E under Chuck Daly 57-25 1W under Pat Riley June 6, 8, 11, 13 9 Joe Dumars DET Finals MVP 27.3 pts, 6.0 ast, 1.8 reb 8 Pistons win their first-ever NBA championship 9 During season, Pat Riley trademarked phrase “Three-peat” Lakers 97 @ Pistons 109 at The Palace of Auburn Hills – Isiah Thomas DET 24 pts, 9 ast; Joe Dumars DET 22 pts Lakers 105 @ Pistons 108 – Joe Dumars DET 33 pts; Magic Johnson LAL injures hamstring, plays only 5 more mins in series Pistons 114 @ Lakers 110 at Great Western Forum – Joe Dumars DET 31 pts; Dennis Rodman DET 19 reb Pistons 105 @ Lakers 97 – Joe Dumars DET 23 pts; James Worthy LAL 40 pts Pistons’ starters – G Isiah Thomas, G Joe Dumars, C Bill Laimbeer, F Mark Aguirre, F Rick Mahorn Lakers’ starters – G Magic Johnson, G Michael Cooper, C Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, F A.C. Green, F James Worthy 1 Los Angeles Lakers defeat Detroit Pistons in 7 9 62-20 1W under Pat Riley 54-28 2E under Chuck Daly June 7, 9, 12, 14, 16, 19, 21 8 James Worthy LAL Finals MVP 22.0 pts, 4.4 ast, 7.4 reb 8 Pistons 105 @ Lakers 93 at Great Western Forum – Adrian Dantley DET 34 pts; Isiah Thomas DET 19 pts, 12 ast Pistons 96 @ Lakers 108 – James Worthy LAL 26 pts, 10 reb, 6 ast; Byron Scott LAL 24 pts; Magic Johnson LAL 11 ast Lakers 99 @ Pistons 86 at Pontiac Silverdome – James Worthy LAL 24 pts; Magic Johnson LAL 18 pts, 14 ast Lakers 86 @ Pistons 111 – Adrian Dantley DET 27 pts; Isiah Thomas DET 9 rb, 12 as; Vinnie Johnson DET 16 pts off bench Lakers 94 @ Pistons 104 – Adrian Dantley DET 25 pts; Bill Laimbeer DET 11 reb; John Salley DET 10 reb Pistons 102 @ Lakers 103 – James Worthy LAL 28 pts; Magic Johnson LAL 19 pts, 22 ast Pistons 105 @ Lakers 108 – James Worthy LAL 36 pts, 16 reb, 10 ast; Magic Johnson LAL 19 pts, 14 ast Lakers’ starters – G Magic Johnson, G Byron Scott, C Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, F A.C. -

Inside … Serving DX'ers Since 1933

1 News DX Serving DX'ers since 1933 Volume 74, No. 6 - November 6, 2006 ISSN 0737-1659) Inside … 11 .. IDXD 2 .. AM Switch 10 .. NRC Contest 3 .. DDXD 14 .. Professional Sports Networks Station Test Calendar scan or retype reprints currently in print; one or WODI NJ 1230 Now to ? 0000-0005 more persons to scan verie letters to be placed on WMRO TN 1560Now-Nov. 13 0100-0600 the NRCDXAS web site; several persons to re- WWNH NH 1340 Nov. 5 2200-0000 search and prepare a book in commemoration of KANA MT 580 Nov. 19 0200-0400 the NRC’s 75th anniversary; a “Confirmed DX’er” KLCY MT 930 Nov. 19 0200-0400 editor; a “DX Targets” editor; a technical column KEIN MT 1310 Nov. 19 0200-0400 editor; a nationwide QSL coordinator (preferably KGVO MT 1290 Nov. 19 0200-0400 a joint NRC/IRCA/WTFDA member); someone to WFIL PA 560 Dec. 10 0500-0600 type e-mail reports for members who don’t have WNTP PA 990 Dec. 10 0500-0600 computers. From the Publisher … This issue of DXN marks the end of an era, sort of. Since 1987 I have used DXN Publishing Schedule, Volume 74 Pagemaker as my desktop publishing software, Iss. Deadline Pub. Date Iss. Deadline Pub. Date and for the past 18 years Pagemaker, from versions 7. Nov. 3 Nov. 13 19. Feb. 2. Feb. 12 3.0 to 7.0.1 has been the DTP of choice for laying 8. Nov. 10 Nov. 20 20. Feb. 9 Feb. 19 out DXN. -

History All-Time Coaching Records All-Time Coaching Records

HISTORY ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS ALL-TIME COACHING RECORDS REGULAR SEASON PLAYOFFS REGULAR SEASON PLAYOFFS CHARLES ECKMAN HERB BROWN SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT LEADERSHIP 1957-58 9-16 .360 1975-76 19-21 .475 4-5 .444 TOTALS 9-16 .360 1976-77 44-38 .537 1-2 .333 1977-78 9-15 .375 RED ROCHA TOTALS 72-74 .493 5-7 .417 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1957-58 24-23 .511 3-4 .429 BOB KAUFFMAN 1958-59 28-44 .389 1-2 .333 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1959-60 13-21 .382 1977-78 29-29 .500 TOTALS 65-88 .425 4-6 .400 TOTALS 29-29 .500 DICK MCGUIRE DICK VITALE SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT PLAYERS 1959-60 17-24 .414 0-2 .000 1978-79 30-52 .366 1960-61 34-45 .430 2-3 .400 1979-80 4-8 .333 1961-62 37-43 .463 5-5 .500 TOTALS 34-60 .362 1962-63 34-46 .425 1-3 .250 RICHIE ADUBATO TOTALS 122-158 .436 8-13 .381 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT CHARLES WOLF 1979-80 12-58 .171 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT TOTALS 12-58 .171 1963-64 23-57 .288 1964-65 2-9 .182 SCOTTY ROBERTSON REVIEW 18-19 TOTALS 25-66 .274 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1980-81 21-61 .256 DAVE DEBUSSCHERE 1981-82 39-43 .476 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1982-83 37-45 .451 1964-65 29-40 .420 TOTALS 97-149 .394 1965-66 22-58 .275 1966-67 28-45 .384 CHUCK DALY TOTALS 79-143 .356 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1983-84 49-33 .598 2-3 .400 DONNIE BUTCHER 1984-85 46-36 .561 5-4 .556 SEASON W-L PCT W-L PCT 1985-86 46-36 .561 1-3 .250 RE 1966-67 2-6 .250 1986-87 52-30 .634 10-5 .667 1967-68 40-42 .488 2-4 .333 1987-88 54-28 .659 14-9 .609 CORDS 1968-69 10-12 .455 1988-89 63-19 .768 15-2 .882 TOTALS 52-60 .464 2-4 .333 -

Opponents Opponents

opponents opponents OPPONENTS opponents opponents Directory Ownership ................................................................Bruce Levenson, Michael Gearon, Steven Belkin, Ed Peskowitz, ..............................................................................Rutherford Seydel, Todd Foreman, Michael Gearon Sr., Beau Turner President, Basketball Operations/General Manager .....................................................................................Danny Ferry Assistant General Manager.........................................................................................................................................Wes Wilcox Senior Advisor, Basketball Operations .....................................................................................................................Rick Sund Head Coach .......................................................... Larry Drew (All-Time: 84-64, .568; All-Time vs Hornets: 1-2, .333) Assistant Coaches ............................................................. Lester Conner, Bob Bender, Kenny Atkinson, Bob Weiss Player Development Instructor ............................................................................................................................Nick Van Exel Strength & Conditioning Coach ........................................................................................................................ Jeff Watkinson Vice President of Public Relations .........................................................................................................................................TBD