Comparing Models of COLLABORATIVE JOURNALISM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Cover 01-2012.Ppp

The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association JANUARY 2012 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers Anxious Dxers Camp out on a Snowy New Years Eve Anticipating huge Discounts on DX Equipment at Ozzy’s House of Antennas. Paul Mitschler Happy New DX Year 2012! Visit Us At www.wtfda.org THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info _______________________________________________________________________________________ We’re back. I hope everyone had an enjoyable holiday season! So far I’ve heard of just one Es event just before Christmas that very briefly made it to FM and another Es event that was noticed by Chris Dunne down in Florida that went briefly to FM from Colombia. F2 skip faded away somewhat as the solar flux dropped down to the 130s. So, all in all, December has been mostly uneventful. But keep looking because anything can still happen. We’ve prepared a “State of the Club” message for this issue. -

Photojournalism Photojournalism

Photojournalism For this section, we'll be looking at photojournalism's impact on shaping people's opinions of the news & world events. Photojournalism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism (the collecting, editing, and presenting of news material for publication or broadcast) that employs images in order to tell a news story. It is now usually understood to refer only to still images, but in some cases the term also refers to video used in broadcast journalism. Photojournalism is distinguished from other close branches of photography (e.g., documentary photography, social documentary photography, street photography or celebrity photography) by complying with a rigid ethical framework which demands that the work be both honest and impartial whilst telling the story in strictly journalistic terms. Photojournalists create pictures that contribute to the news media, and help communities connect with one other. Photojournalists must be well informed and knowledgeable about events happening right outside their door. They deliver news in a creative format that is not only informative, but also entertaining. Timeliness The images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events. Objectivity The situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone. Narrative The images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to audiences. Like a writer, a photojournalist is a reporter, but he or she must often make decisions instantly and carry photographic equipment, often while exposed to significant obstacles (e.g., physical danger, weather, crowds, physical access). -

How to Fund Investigative Journalism Insights from the Field and Its Key Donors Imprint

EDITION DW AKADEMIE | 2019 How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Imprint PUBLISHER RESPONSIBLE PUBLISHED Deutsche Welle Jan Lublinski September 2019 53110 Bonn Carsten von Nahmen Germany © DW Akademie EDITORS AUTHOR Petra Aldenrath Sameer Padania Nadine Jurrat How to fund investigative journalism Insights from the field and its key donors Sameer Padania ABOUT THE REPORT About the report This report is designed to give funders a succinct and accessible introduction to the practice of funding investigative journalism around the world, via major contemporary debates, trends and challenges in the field. It is part of a series from DW Akademie looking at practices, challenges and futures of investigative journalism (IJ) around the world. The paper is intended as a stepping stone, or a springboard, for those who know little about investigative journalism, but who would like to know more. It is not a defense, a mapping or a history of the field, either globally or regionally; nor is it a description of or guide to how to conduct investigations or an examination of investigative techniques. These are widely available in other areas and (to some extent) in other languages already. Rooted in 17 in-depth expert interviews and wide-ranging desk research, this report sets out big-picture challenges and oppor- tunities facing the IJ field both in general, and in specific regions of the world. It provides donors with an overview of the main ways this often precarious field is financed in newsrooms and units large and small. Finally it provides high-level practical ad- vice — from experienced donors and the IJ field — to help new, prospective or curious donors to the field to find out how to get started, and what is important to do, and not to do. -

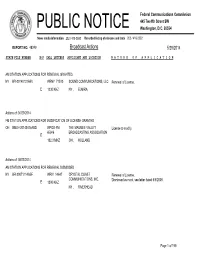

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

Michigan Strategic Fund

MICHIGAN STRATEGIC FUND MEMORANDUM DATE: March 12, 2021 TO: The Honorable Gretchen Whitmer, Governor of Michigan Members of the Michigan Legislature FROM: Mark Burton, President, Michigan Strategic Fund SUBJECT: FY 2020 MSF/MEDC Annual Report The Michigan Strategic Fund (MSF) is required to submit an annual report to the Governor and the Michigan Legislature summarizing activities and program spending for the previous fiscal year. This requirement is contained within the Michigan Strategic Fund Act (Public Act 270 of 1984) and budget boilerplate. Attached you will find the annual report for the MSF and the Michigan Economic Development Corporation (MEDC) as required in by Section 1004 of Public Act 166 of 2020 as well as the consolidated MSF Act reporting requirements found in Section 125.2009 of the MSF Act. Additionally, you will find an executive summary at the forefront of the report that provides a year-in-review snapshot of activities, including COVID-19 relief programs to support Michigan businesses and communities. To further consolidate legislative reporting, the attachment includes the following budget boilerplate reports: • Michigan Business Development Program and Michigan Community Revitalization Program amendments (Section 1006) • Corporate budget, revenue, expenditures/activities and state vs. corporate FTEs (Section 1007) • Jobs for Michigan Investment Fund (Section 1010) • Michigan Film incentives status (Section 1032) • Michigan Film & Digital Media Office activities ( Section 1033) • Business incubators and accelerators annual report (Section 1034) The following programs are not included in the FY 2020 report: • The Community College Skilled Trades Equipment Program was created in 2015 to provide funding to community colleges to purchase equipment required for educational programs in high-wage, high-skill, and high-demand occupations. -

I:\28947 Ind Law Rev 47-1\47Masthead.Wpd

CITIGROUP: A CASE STUDY IN MANAGERIAL AND REGULATORY FAILURES ARTHUR E. WILMARTH, JR.* “I don’t think [Citigroup is] too big to manage or govern at all . [W]hen you look at the results of what happened, you have to say it was a great success.” Sanford “Sandy” Weill, chairman of Citigroup, 1998-20061 “Our job is to set a tone at the top to incent people to do the right thing and to set up safety nets to catch people who make mistakes or do the wrong thing and correct those as quickly as possible. And it is working. It is working.” Charles O. “Chuck” Prince III, CEO of Citigroup, 2003-20072 “People know I was concerned about the markets. Clearly, there were things wrong. But I don’t know of anyone who foresaw a perfect storm, and that’s what we’ve had here.” Robert Rubin, chairman of Citigroup’s executive committee, 1999- 20093 “I do not think we did enough as [regulators] with the authority we had to help contain the risks that ultimately emerged in [Citigroup].” Timothy Geithner, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2003-2009; Secretary of the Treasury, 2009-20134 * Professor of Law and Executive Director of the Center for Law, Economics & Finance, George Washington University Law School. I wish to thank GW Law School and Dean Greg Maggs for a summer research grant that supported my work on this Article. I am indebted to Eric Klein, a member of GW Law’s Class of 2015, and Germaine Leahy, Head of Reference in the Jacob Burns Law Library, for their superb research assistance. -

Turning a Blind Eye: Why Washington Keeps Giving in to Wall Street

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2013 Turning a Blind Eye: Why Washington Keeps Giving In to Wall Street Arthur E. Wilmarth Jr. George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr., Turning a Blind Eye: Why Washington Keeps Giving In to Wall Street, 81 University of Cincinnati Law Review 1283-1446 (2013). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GW Law School Public Law and Legal Theory Paper No. 2013‐117 GW Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2013‐117 Turning a Blind Eye: Why Washington Keeps Giving In to Wall Street Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr. 2013 81 U. CIN. L. REV. 1283-1446 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from the Social Science Research Network: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2327872 TURNING A BLIND EYE: WHY WASHINGTON KEEPS GIVING IN TO WALL STREET Arthur E. Wilmarth, Jr.* As the Dodd–Frank Act approaches its third anniversary in mid-2013, federal regulators have missed deadlines for more than 60% of the required implementing rules. The financial industry has undermined Dodd–Frank by lobbying regulators to delay or weaken rules, by suing to overturn completed rules, and by pushing for legislation to freeze agency budgets and repeal Dodd–Frank’s key mandates. -

What Is Sustainable Agriculture?

the .Practical Farmer .. r ~,., ' Annual Conference Jan. 9 & 1 0 ............... I Pg. 3 Dan Specht: The OP-Corn Kid ....•...•......... I Pg. 8 Apples in Iowa •••••.••••..•.••.••..•••.••••.•.••...•....•..••••.•..•.•...•.•.•. I Pg. 20 On-farm Research: OP Com ............................................. ! Pg. 24 New Resource Section ..................................................... ! Pg. 26 ··- Contents ~ {-~·. ·-:;;..~._:"', Annual Conference .............................................. 3 Focus on Food: Apples ...................................... 20 Board News ......................................................... 6 Calendar ............................................................ 23 Member Profile: Dan Specht ................................ 8 On-Farm Research: OP Corn ............................ 24 PFI Camp ........................................ .................. 12 Resources ................................. ......................... 26 Field Day Report ................................................ 14 Member Perspectives: What is Sustainable Ag? .. 28 Practical Farmers of Peru .................................. 15 Reflections: Remembering the Sacred .............. 29 Staff and Program Updates ........................... 16-17 PFI Merchandise ............................................... 30 Member News .............................................. 18-19 Join PFI ............................................................. 31 Cover photo by Rick Exner: Oats discussion at Stc'A! and June Weis field day, 1999 -

Comparative Models of Cooperative Journalism

COMPARATIVE MODELS OF COOPERATIVE JOURNALISM by Mercedes N . Rodriguez Journalism Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. Research Question ................................................................................................... 3 II . Literature Review ................................................................................................... 6 II . Methodology ........................................................................................................ 17 IV . Discussion .......................................................................................................... 19 V. Conclusion …....................................................................................................... 27 Bibliography ................................................................................ 28 2 Research Question: What are the advantage and disadvantages of cooperative journalism between professional journalists? Between established newsrooms and journalism students? Between citizen reporters and journalists from an established media outlet? And finally , what can be gained from cooperation between non-journalism professionals and professional journalists? Purpose Statement: The purpose of this study is to define the varying forms of cooperative journalism , its political implications , current uses , and potential ethical problems , and to determine if it is a viable option to counteract the decline of the traditional newsroom . Variables -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

Attachment a Fm Noncommercial Educational Mx

ATTACHMENT A FM NONCOMMERCIAL EDUCATIONAL MX GROUPS FOR COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS MX LEAD GROUP CUTOFF FILE NUMBER DATE NUMBER CITY ST APPLICANT 88031E 08/22/84 A BPED 19840322CA BATON ROUGE LA REAL LIFE EDUCATIONAL FOUND. OF BATON ROUGE, INC. 88031E BPED 19840822IF BATON ROUGE LA JIMMY SWAGGART MINISTRIES 880611 01/10/90 A BPED 19880610ML REDDING CA THE UNIV.FOUND. CA STATE UNIV, CHICO 880611 B BPED 19900129MH REDDING CA STATE OF OREGON 89101E 12/07/93 A BPED 19891019MA CROWN POINT IN HYLES-ANDERSON COLLEGE 89101E B BPED 19910409MF CROWN POINT IN THE MOODY BIBLE INSTITUTE 92102E 03/24/93 A BPED 19921026MA WHITEHALL OH LOU SMITH MINISTRIES, INC. 92102E A BPED 19921029MB COLUMBUS OH CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING SERVICES, INC 92102E B BPED 19921104MA COLUMBUS OH THE CEDARVILLE COLLEGE 94106E 07/14/95 A BPED 19941026MA NORMAN OK AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION 94106E B BPED 19950714MD NORMAN OK SISTER SHERRY LYNN FOUNDATION INC 941116 03/28/96 A BPED 19941114MA ASHLAND KY AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION 941116 B BPED 19960328MC ASHLAND KY POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 941116 B BPED 19960328MI HURRICANE WV POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 94114E 11/08/95 A BPED 19941103MC BRISTOL VA AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION 94114E B BPED 19951023IB EMORY VA EMORY & HENRY COLLEGE 94114E B BPED 19951108NC BRISTOL VA VIRGINIA TECH FOUNDATION, INC. 94123E 05/24/95 A BPED 19941209MB OTTUMWA IA GRASSROOTS BROADCASTING, CO., INC. 94123E B BPED 19950213MB OTTUMWA IA IOWA ST UN OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 94123E B BPED 19950515ML FAIRFIELD IA AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION 950215 05/03/96 A BPED 19950210MA MCCLOUD CA SOUTHERN OREGON STATE COLLEGE 950215 B BPED 19960503MG MCCLOUD CA FATIMA RESPONSE INC DBA 95031E 07/14/95 A BPED 19950327MA REDDING CA CHRISTIAN ARTS AND EDUCATION, INC. -

FCC-01-64A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 01-64 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Reexamination of the Comparative Standards for ) Noncommercial Educational Applicants ) MM Docket No. 95-31 ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: February 15, 2001 Released: February 28, 2001 By the Commission: Commissioner Furchtgott-Roth issuing a statement TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY ....................................................................................................2 III. NEW SELECTION PROCESS..........................................................................................................4 IV. REQUESTS FOR RECONSIDERATION AND CLARIFICATION..................................................9 A. Objections to Overall Process.....................................................................................................10 1. Rejection of Lotteries...........................................................................................................11 2. Constitutional Concerns.......................................................................................................15 B. Time for Calculating Points/Enhancement of Proposals ..............................................................22 1. Timing for Future Applications............................................................................................23