The Napoleon Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Under Wellington's Command, by G

1 Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Under Wellington's Command, by G. A. Henty 2 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Under Wellington's Command, by G. A. Henty The Project Gutenberg EBook of Under Wellington's Command, by G. A. Henty This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Under Wellington's Command A Tale of the Peninsular War Author: G. A. Henty Illustrator: Wal. Paget Release Date: December 29, 2006 [EBook #20207] Under Wellington's Command, by G. A. Henty 3 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK UNDER WELLINGTON'S COMMAND *** Produced by Martin Robb Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War by G. A. Henty. Contents Preface. Chapter 1 4 Chapter 1 : A Detached Force. Chapter 2 5 Chapter 2 : Talavera. Chapter 3 6 Chapter 3 : Prisoners. Chapter 4 7 Chapter 4 : Guerillas. Chapter 5 8 Chapter 5 : An Escape. -

The Education of a Field Marshal :: Wellington in India and Iberia

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1992 The education of a field am rshal :: Wellington in India and Iberia/ David G. Cotter University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Cotter, David G., "The ducae tion of a field marshal :: Wellington in India and Iberia/" (1992). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1417. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1417 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EDUCATION OF A FIELD MARSHAL WELLINGTON IN INDIA AND IBERIA A Thesis Presented by DAVID' G. COTTER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1992 Department of History Copyright by David G. Cotter 1992 All Rights Reserved ' THE EDUCATION OF A FIELD MARSHAL WELLINGTON IN INDIA AND IBERIA A Thesis Presented by DAVID G. COTTER Approved as to style and content by Franklin B. Wickwire, Chair )1 Mary B/ Wickwire 'Mary /5. Wilson Robert E. Jones^ Department Chai^r, History ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to all in the History department at the University of Massachusetts, especially Professors Stephen Pelz, Marvin Swartz, R. Dean Ware, Mary Wickwire and Mary Wilson. I am particularly indebted to Professor Franklin Wickwire. He performed as instructor, editor, devil's advocate, mentor and friend. -

Wellington's Two-Front War: the Peninsular Campaigns, 1808-1814 Joshua L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Wellington's Two-Front War: The Peninsular Campaigns, 1808-1814 Joshua L. Moon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WELLINGTON’S TWO-FRONT WAR: THE PENINSULAR CAMPAIGNS, 1808 - 1814 By JOSHUA L. MOON A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History In partial fulfillment of the Requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Joshua L. Moon defended on 7 April 2005. __________________________________ Donald D. Horward Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ______________________________ Edward Wynot Committee Member ______________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named Committee members ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS No one can write a dissertation alone and I would like to thank a great many people who have made this possible. Foremost, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Donald D. Horward. Not only has he tirelessly directed my studies, but also throughout this process he has inculcated a love for Napoleonic History in me that will last a lifetime. A consummate scholar and teacher, his presence dominates the field. I am immensely proud to have his name on this work and I owe an immeasurable amount of gratitude to him and the Institute of Napoleon and French Revolution at Florida State University. -

The Battle of Waterloo Background

The Battle of Waterloo Background In 1809 Wellington gained his first significant victory in Spain at the Battle of Talavera but the French had three armies in that country, each larger than his own. In order to establish a serious force and to wear Marshal Massena down, he retired behind the well-prepared lines of Torres Vedras, near Lisbon. The French were unable to force these defences and in 1811, Wellington felt strong enough to issue forth from his fortifications and after three years' hard fighting worked his way through Spain, and step by step beat back the Napoleonic forces across the Pyrenees into France. He won the great battles of Salamanca, Vitoria, and Orthez; stormed the cities of Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajos, and San Sebastian; fought for six days amidst the rocks passes of the Pyrenees; and at last, on the 10th of April 1814 gained decisive victory at Battle of Toulouse. He had trained and created an experienced army with which "he could go anywhere and do anything"; and now he stood with it upon "the sacred soil of France". Only six months before, Napoleon, who had lost four hundred thousand men between Moscow and the Niemen on his disastrous retreat from Russia, had been defeated by the Allies in the great Battle of Leipzig and the Emperor of Russia and the King of Prussia had already entered Paris at the head of their victorious armies Napoleon was compelled to abdicate, the Bourbons returned to the throne of France, and the beaten Emperor was banished to the little island of Elba, of which he was made king. -

All for the King's Shilling

ALL FOR THE KING’S SHILLING AN ANALYSIS OF THE CAMPAIGN AND COMBAT EXPERIENCES OF THE BRITISH SOLDIER IN THE PENINSULAR WAR, 1808-1814 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Edward James Coss, M.A. The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor John Guilmartin, Adviser _______________________________ Professor Mark Grimsley Adviser Professor John Lynn Graduate Program in History Copyright by Edward J. Coss 2005 ABSTRACT The British soldier of the Peninsular War, 1808-1814, has in the last two centuries acquired a reputation as being a thief, scoundrel, criminal, and undesirable social outcast. Labeled “the scum of the earth” by their commander, the Duke of Wellington, these men were supposedly swept from the streets and jails into the army. Their unmatched success on the battlefield has been attributed to their savage and criminal natures and Wellington’s tactical ability. A detailed investigation, combining heretofore unmined demographic data, primary source accounts, and nutritional analysis, reveals a picture of the British soldier that presents his campaign and combat behaviors in a different light. Most likely an unemployed laborer or textile worker, the soldier enlisted because of economic need. A growing population, the impact of the war, and the transition from hand-made goods to machined products displaced large numbers of workers. Men joined the army in hopes of receiving regular wages and meals. In this they would be sorely disappointed. Enlisted for life, the soldier’s new primary social group became his surrogate family. -

Hobhouse and the Hundred Days

116 The Hundred Days, March 11th-July 24th 1815 The Hundred Days March 11th-July 24th 1815 Edited from B.L.Add.Mss. 47232, and Berg Collection Volumes 2, 3 and 4: Broughton Holograph Diaries, Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Saturday March 11th 1815: Received this morning from my father the following letter: Lord Cochrane has escaped from prison1 – Bounaparte has escaped from Elba2 – I write this from the House of Commons and the intelligence in both cases seems to rest on good authority and is believed. Benjamin Hobhouse Both are certainly true. Cullen3 came down today and confirmed the whole of both. From the first I feel sure of Napoleon’s success. I received a letter [from] Lord John Townshend4 apologising for his rudeness, but annexing such comments as require a hint from me at the close of the controversy. Sunday March 12th 1815: Finish reading the Αυτοχεδιοι Ετοχασµοι of Coray.5 1: Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald (1775-1860) admiral. Implicated unfairly in a financial scandal, he had been imprisoned by the establishment enemies he had made in his exposure of Admiralty corruption. He was recaptured (see below, 21 Mar 1815). He later became famous as the friend and naval assistant of Simon Bolivar. 2: Napoleon left Elba on March 26th. 3: Cullen was a lawyer friend of H., at Lincoln’s Inn. 4: Lord John Townshend. (1757-1833); H. has been planning to compete against his son as M.P. for Cambridge University, which has made discord for which Townshend has apologised. -

Francis Newport and the Peninsula War

Francis Newport and the Peninsula War By Mark Wareham, updated 2nd August 2013 An officer (left) and private in the uniform of the 40th Regiment as it was in 1812. Francis would have looked exactly like the private pictured here, with his British redcoat, grey trousers and carrying the ‘brown bess’ flintlock musket. From Wikipedia. 1 Introduction In mid-2011 I discovered online a list of soldiers of the 40th Regiment of Foot who were not Chelsea pensioners but who were awarded medals for having served in the Peninsula War of 1808 to 1814. On that list I found the name of my great x 4 grandfather Francis Newport (abbreviated to Fra’s Newport). Francis is my ancestor through my maternal grandmother’s mother Emma Jane (or Emily) Newport. Although there is little detail surrounding this name on the list, it is very likely that the person shown on the regimental list as ‘Fra’s Newport’ is Francis who was born in 1783 at Baltonsborough (shown as ‘Baltonsbury’ on the map below) in Somerset, to Daniel and Mary Newport. It is not a common name (although there was another Francis Newport who was born in about 1781 in Ireland who is living in Bristol by 1841) and a period of service from 1808 to 1814 fits perfectly because he would have been about 25 years old when this campaign started, a good age to become someone to go ‘over the hills and far away’. Francis Newport of Baltonsborough did not marry until 1816, when he was 33, rather late in life for a marriage at the time, and there is no evidence of him being in England or Somerset between his baptism and his marriage. -

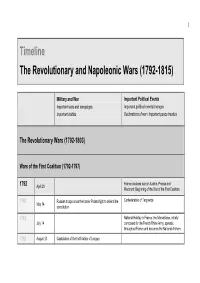

Timeline 1792-1815

1 Timeline The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) Military and War Important Political Events Important wars and campaigns Important political events/changes Important battles Declarations of war / Important peace treaties The Revolutionary Wars (1792-1803) Wars of the First Coalition (1792-1797) France declares war on Austria, Prussia and 1792 April 20 Piedmont: Beginning of the War of the First Coalition 1792 Russian troops cross the border Poland fight to defend the Confederation of Targowica May 14 constitution 1792 National Holiday in France: the Marseillaise, initially July 14 composed for the French Rhine Army, spreads throughout France and becomes the National Anthem 1792 August 23 Capitulation of the fortification of Longwy 2 1792 September 2 Capitulation of the fortification of Verdun September First phase of the „terreur“ (so called september 1792 5-7 murders) August/ 1792 Upheavals in Brittany, Mayenne and Vendée September Battle of Valmy (France versus Prussia/Austria) French 1792 September20 Victory 1792 September 21 Establishment of the first French Republic 1792 September 22 Die Armee unter Montesquiou dringt nach Savoyen vor 1792 September 23 The Austrians encircle Lille The convention splits his forces in eight armies: North, 1792 October 1 Ardennes, Moselle, Rhine, Vosges, Alps, Pyrénées, Interior 1792 October 3 Revolutionary troops occupy Basel 1792 October 4 Revolutionary troops occupy Worms 1792 October 27 Revolutionary troops enter Belgium The revolutionary troops occupy Jemappes (part of the 1792 November 6 austrian part of the Netherlands) 1792 November 9 Revolutionary troops occupy the Palatinate 1793 January 21 Louis XVI guillotined 1793 Russia and Prussia signed the Second Partition Great January 23 Poland with parts of Mazovia (Mazowsze) to Prussia; Podolia, Volhynia, and Lithuanian to Russia. -

The Battle of Talavera, 27 -28 July 1809

The Battle of Talavera, 27th-28th July 1809 The battle was fought between an Anglo-Spanish force under Wellesley and Cuesta and a French Army under Joseph I.. 1 MAP. THE BATTLEFIELD OF TALAVERA A.- Dawn attack B.- Afternoon attack MAP NOTES 1.1 The buildings of Talavera have a “+2” combat modifier. The city wall and field entrenchments are fortifications and have a “+2” combat modifier. The Pajar de Vergara Redoubt is a fortification with a “+3” combat modifier. 1.2 Cavalry and artillery treat woods (actually olive groves and orchards) as rough ground for movement purposes, unless they are on a road in limbered/column/march column formation. 1.3 The Portiña stream is fully passable for infantry and cavalry but artillery must cross at the bridge (B2). The Portiña between Cascajal and Medellín count as rough terrain. For the dried ditch (C2) see 4.8. The Tajo River is not fordable. 1.4 The terrain squares are 40x40 cm (15.7”x15.7”) 1/8 29/08/2006 (11:38) 2 TALAVERA ORDERS OF BATTLE1 Allied Army. Wellington commands all British units and officers and Cuesta commands all Spanish units and officers. British officers have no effect upon Spanish units and officers for command purposes, and vice versa (See 4.2 b). Divisional foot batteries (marked *) must be assigned by Wellington or Cuesta for direct fire support to Infantry and Cavalry units and deployed accordingly. A maximum of 1 battery by army may be maintained in reserve. (3) British Army of Portugal (B) Wellington 14"G(8/10)+3D [8M] (369 points) (1) 1st Division (1) Sherbrooke 3"A(6)+1[2F] -

The Role of the British Cavalry 1808-1814 Mark T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Command and Control in the Peninsula: The Role of the British Cavalry 1808-1814 Mark T. Gerges Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES COMMAND AND CONTROL IN THE PENINSULA: THE ROLE OF THE BRITISH CAVALRY 1808-1814 By MARK T. GERGES A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Mark T. Gerges All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Mark T. Gerges defended on 15 June 2005. ______________________________ Donald D. Horward Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Alec Hargreaves Outside Committee Member ______________________________ William O. Oldson Committee Member ______________________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member ______________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies had verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With an endeavor of this scale, the list of people that facilitated my research and provided guidance over the years is vast. I owe a debt of thanks to the staff of the Florida State University’s Strozier Library Special Collections and sub-basement staff, where this project started. The archives in Great Britain provided the guidance and assistance I needed to successfully mine their vast holdings in the limited time I had. I would like to thank C.M. Woolgar in particular and the staff of the Special Collections at the University of Southampton for their assistance with the Wellington Papers; the staff of the National Army Museum, Chelsea, London, in using their valuable and under-utilized journals and correspondence; and the staff of the Public Records Office, Kew Gardens. -

The Romance of War, Or, the Highlanders in Spain: the Peninsular War and the British Novel

THE ROMANCE OF WAR, OR, THE HIGHLANDERS IN SPAIN: THE PENINSULAR WAR AND THE BRITISH NOVEL Brian J. DENDLE University of Kentucky Wellington's Peninsular campaigns aroused considerable interest among British historians and reading public throughout the nineteenth century and even into the present decade of the twentieth century. The most recent historian of the war, David Gates, in The Spanish Ulcer (1986), counts some three hundred published personal memoirs and diaries, mainly British, in his bibliography. The war in the Iberian Península was savagely fought by British, Spanish, Portuguese, and French troops, as well as by Spanish and Portuguese irregular forces (the guerrilleros). When not fighting, British and French troops at times fraternized and observed a chivalrous respect for each other. The sufferings caused by the war were immense, including the looting and devastation of French-occupied Spain, the starvation of many Spaniards and Portuguese, and a very high casualty rate among the troops involved. Indeed, British soldiers frequently collapsed and died under the excessive loads they were compelled to carry'.For the British, the campaign represented the success of a small and previoüsly despised army, under the remarkable leadership of Wellington, over Napoleon's veterans. Spanish historians, on the other hand, stress the Spanish contribution to the successful outcome of the war2. 1. For a vivid first-hand account of the savage discipline enforced in Wellington's army and the atrocious sufferings of British soldiers, especially during the retíeat to Vigo, see Christopher Hibbert, cd., Recollections ofRifleman Harris, Hamden, Connecticut, Archon Books, 1970. 2. The American literary scholar Roger L. -

The French Invasions of Portugal 1807-1811: Rebellion, Reaction and Resistance

The French Invasions of Portugal 1807-1811: rebellion, reaction and resistance Anthony Gray MA by Research University of York Department of History Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies June 2011 Abstract Portugal’s involvement in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars resulted in substantial economic, political and social change revealing interconnections between state and economy that have not been acknowledged fully within the existing literature. On the one hand, economic and political change was precipitated by the flight of Dom João, the removal of the court to Rio de Janeiro, and the appointment of a regency council in Lisbon: events that were the result of much more than the mere confluence of external drivers and internal pressures in Europe, however complex and compelling they may have been at the time. Although governance in Portugal had been handed over to the regency council strict limitations were imposed on its autonomy. Once Lisbon was occupied, and French military government imposed on Portugal, her continued role as entrepôt, linking the South Atlantic economy to that of Europe, could not be guaranteed. Brazil’s ports were therefore opened to foreign vessels and restrictions on agriculture, manufacture and inter-regional trade in the colonies were lifted presaging a transition from neo-mercantilism to proto-industrialised capitalism. The meanings of this dislocation of political power and the shift of government from metropolis to colony were complex, not least in relation to the location and limits of absolutist authority. The immediate results of which were a series of popular insurrections in Portugal, a swift response by the French military government and conservative reaction by Portuguese élites, leading to widespread popular resistance in 1808 and 1809 and, subsequently, Portugal’s wholesale involvement in the Peninsular War with severe and deleterious effects on the Portuguese population and economy.