A History of the Rush University, College of Nursing and the Development of the Unification Model 1972-1988

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Going the Extra Mile with Care and Support

A quarterly publication of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine Medical College of Wisconsin Autumn 2019 Notes from the Department Chair GOING THE EXTRA MILE WITH CARE AND SUPPORT PSYCHED was created as part of an action plan to improve communication and engagement with- in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine. Over the past five years we have had many editions of the newsletter based upon the Department themes that cover all of our missions. We have published editions in the past that have focused on What I witnessed in response to the need of MCW and the equity and inclusion, expanding access to mental health care, challenges faced by our faculty, staff, and trainees has been finding purpose in our work, the importance of goal setting, nothing short of uplifting and inspiring. I witnessed individ- and the importance and value of mentorship, amongst other uals in the Department stepping up to support one other in timely themes. ways better than I could have ever dreamed of. I witnessed my Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine fam- PSYCHED editor and creative director Thom Ertl has done ily go the extra mile caring for and supporting one another a tremendous job in organizing each edition in an artful way and supporting our greater MCW family. It brings tears of that includes both an attention to detail and a visual attrac- joy to my eyes to see this giving and caring spirit. tiveness to the finished product. Editorial team members It is during times like Joy Ehlenbach, Karen Hamilton, Kristine James, and Dawn these that I realize What I witnessed in response Norby have all contributed greatly in creating a meaningful how blessed I am to to the need of MCW, the product. -

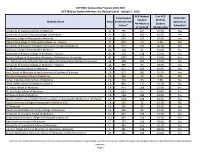

ACP IMIG Sponsorship Program 2020-2021

ACP IMIG Sponsorship Program 2020-2021 ACP Medical Student Members by Medical School - October 1, 2020 ACP Medical % of ACP Total Student 2020-2021 Student Medical Medical School State Enrollment Per Application Members as Student School* Submitted of 10/1/20 Membership University of Alabama School of Medicine AL 799 124 15.5% Yes University of South Alabama College of Medicine AL 294 182 61.9% Yes Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine AL 651 127 19.5% Yes Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine - Auburn AL 632 23 3.6% No University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences College of Medicine AR 715 132 18.5% Yes Arkansas College of Osteopathic Medicine AR 318 51 16.0% Yes University of Arizona College of Medicine - Tucson AZ 523 118 22.6% Yes Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine of Midwestern University AZ 1005 151 15.0% Yes A.T. Still University of Health Sciences School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona AZ 428 105 24.5% Yes University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix AZ 339 64 18.9% Yes UC San Francisco School of Medicine CA 813 169 20.8% Yes Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California CA 812 181 22.3% Yes Stanford University School of Medicine CA 530 30 5.7% No Loma Linda University School of Medicine CA 724 43 5.9% Yes David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA CA 856 117 13.7% Yes UC Irvine School of Medicine CA 477 108 22.6% Yes UC San Diego School of Medicine CA 622 67 10.8% Yes UC Davis School of Medicine CA 503 100 19.9% Yes Western University of Health Sciences College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific CA 1352 138 10.2% Yes Touro University College of Osteopathic Medicine (CA) CA 545 72 13.2% No UC Riverside CA 292 89 30.5% Yes California Northstate University College of Medicine CA 382 89 23.3% Yes University of Colorado School of Medicine CO 823 159 19.3% Yes Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine CO 891 120 13.5% Yes Yale University School of Medicine CT 557 100 18.0% Yes University of Connecticut School of Medicine CT 483 155 32.1% Yes Frank H. -

RUSH MEDICAL COLLEGE CLASS of 2016

RUSH MEDICAL COLLEGE CLASS of 2016 POSTGRADUATE APPOINTMENTS NUMBER MATCHED BY SPECIALTY AND INSTITUTION NUMBER MATCHED BY SPECIALTY AND INSTITUTION Anesthesiology Emergency Medicine/Family Medicine 1 Mayo School of Grad Med Educ-MN 1 Christiana Care-DE 2 Rush University Med Ctr-IL Total: 1 1 U Arizona COM at Tucson 1 U Illinois COM-Chicago Family Medicine 1 UC San Francisco-CA 1 UCLA Medical Center-CA 1 Advocate IL Masonic Med Ctr 1 Univ of Chicago Med Ctr-IL 1 Grtr Lawrence Fam Hlth Ctr-MA 1 Hinsdale Hospital-IL Total: 8 1 Kaiser Permanente-San Diego-CA 1 Loyola Univ Med Ctr-IL Child Neurology 2 MacNeal Hospital-IL 1 Loma Linda University-CA 1 Med Coll Wisconsin Affil Hosps 1 Northwestern McGaw/NMH/VA-IL Total: 1 1 Providence Health-OR Emergency Medicine 1 Resurrection Med Ctr-IL 1 U Illinois COM-Chicago 2 Advocate Christ Med Ctr-IL 1 U Michigan Hosps-Ann Arbor 1 Allegheny Gen Hosp-PA 1 U Wisconsin SOM and Public Health 1 Cook County-Stroger Hospital-IL 1 UC Irvine Med Ctr-CA 1 Detroit Med Ctr/WSU-MI 1 Valley Med Ctr-WA 1 Hennepin Co Med Ctr-MN Total: 1 Icahn SOM Beth Israel-NY 16 1 Indiana Univ Sch Of Med 2 Resurrection Med Ctr-IL 2 U Illinois COM-Chicago Total: 12 All efforts for accuracy of this information were made by the OMSP. 1 NUMBER MATCHED BY SPECIALTY AND INSTITUTION Internal Medicine Obstetrics and Gynecology 1 Baylor Coll Med-Houston-TX 1 Duke Univ Med Ctr-NC 2 Cook County-Stroger Hospital-IL 1 U Minnesota Med School 1 George Washington Univ-DC 1 Washington Hospital Ctr-DC 1 Henry Ford HSC-MI Total: 3 1 Loyola Univ Med -

JNR0120SE Globalprofile.Pdf

JOURNAL OF NURSING REGULATION VOLUME 10 · SPECIAL ISSUE · JANUARY 2020 THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF STATE BOARDS OF NURSING JOURNAL Volume 10 Volume OF • Special Issue Issue Special NURSING • January 2020 January REGULATION Advancing Nursing Excellence for Public Protection A Global Profile of Nursing Regulation, Education, and Practice National Council of State Boards of Nursing Pages 1–116 Pages JOURNAL OFNURSING REGULATION Official publication of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing Editor-in-Chief Editorial Advisory Board Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, FAAN Mohammed Arsiwala, MD MT Meadows, DNP, RN, MS, MBA Chief Officer, Nursing Regulation President Director of Professional Practice, AONE National Council of State Boards of Nursing Michigan Urgent Care Executive Director, AONE Foundation Chicago, Illinois Livonia, Michigan Chicago, Illinois Chief Executive Officer Kathy Bettinardi-Angres, Paula R. Meyer, MSN, RN David C. Benton, RGN, PhD, FFNF, FRCN, APN-BC, MS, RN, CADC Executive Director FAAN Professional Assessment Coordinator, Washington State Department of Research Editors Positive Sobriety Institute Health Nursing Care Quality Allison Squires, PhD, RN, FAAN Adjunct Faculty, Rush University Assurance Commission Brendan Martin, PhD Department of Nursing Olympia, Washington Chicago, Illinois NCSBN Board of Directors Barbara Morvant, MN, RN President Shirley A. Brekken, MS, RN, FAAN Regulatory Policy Consultant Julia George, MSN, RN, FRE Executive Director Baton Rouge, Louisiana President-elect Minnesota Board of Nursing Jim Cleghorn, MA Minneapolis, Minnesota Ann L. O’Sullivan, PhD, CRNP, FAAN Treasurer Professor of Primary Care Nursing Adrian Guerrero, CPM Nancy J. Brent, MS, JD, RN Dr. Hildegarde Reynolds Endowed Term Area I Director Attorney At Law Professor of Primary Care Nursing Cynthia LaBonde, MN, RN Wilmette, Illinois University of Pennsylvania Area II Director Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Lori Scheidt, MBA-HCM Sean Clarke, RN, PhD, FAAN Area III Director Executive Vice Dean and Professor Pamela J. -

Melissa Seecharan Signs in the Sand by the Time I Sealed the Very Last

Seecharan 1 Melissa Seecharan Signs in the Sand By the time I sealed the very last moving box, the bedroom blinds had begun to slash the afternoon sunlight, casting all sorts of stripes across my wooden, bedroom floor. I leaned backwards, straight into a pile of clunky shipping containers, each one prodding at me. Regardless, I remained seated on the floor, watching as hazes of fine dust floated aimlessly above the mound of surrounding cardboard, like flocks of vagrant particles. The hum of industrious air-conditioning unit became an unremitting monotone. Somewhere in the distance, a car door slammed. I snapped out of it. Nikolai. The red hulk of his Toyota Camry gleaned from its position in the driveway. I changed quickly, grabbed my backpack, and tucked the last bit of my babysitting money into my jeans’ back pocket. I waited until my mother’s voice sounded from the foyer, before wading through the waist-high boxes and rushing out of the room, leaving the mountainous containers behind. I completely lost track of the time. He stood at the entrance, one hand in his pocket, conversing casually with my mother. His blue eyes sparkled wildly with enthusiasm, and the hovering sun highlighted strands of his golden hair. A grin spread across his face when I came flying down the stairs. “Sorry,” I breathed, still trying to free my hair from the sloppy bun sagging down my head. “I didn’t think it would take me this long.” “I can come back later,” Nikolai offered. “Or I could help you, if you need it.” “Oh, don’t worry about it.” I peered at his car in the driveway. -

Department of Health Services

State of California—Health and Human Services Agency Department of Health Services DIANA M. BONTÁ, R.N., Dr. P.H. GRAY DAVIS Director Governor July 16, 2003 Joseph Hafkenschiel, President California Association for Health Services at Home 723 S Street Sacramento, CA 95814 Dear Mr. Hafkenschiel: Thank you for your letter dated April 25, 2003 to the Department’s Licensing and Certification Program (L&C) regarding the use of unlicensed assistive personnel in both licensed and unlicensed agencies providing services in patients’ homes. As you well know, L&C is responsible for licensing and certifying Home Health Agencies (HHAs) under state and federal laws and regulations. L&C consulted extensively with the Department’s Office of Legal Services in researching the questions you posed and preparing appropriate responses to them. This letter will restate your original question and then provide L&C’s response on a question-by-question basis. Question 1: May an unlicensed agency provide a licensed nurse (registered nurse [RN] or licensed vocational nurse [LVN]) to render skilled services (medication set ups, diabetes testing, insulin injections, etc.) to patients in their temporary or permanent places of residence, if these services were not ordered by a physician? Response: No. An unlicensed agency cannot provide a RN or LVN to render skilled services to patients in their temporary or permanent places of residence, whether or not the services were ordered by a physician. By providing the services of licensed nurses, an unlicensed agency is operating a home health agency, because its business activities come within the statutory definition of a home health agency in Health and Safety Code section 1727 (a). -

Curriculum Vitae

Joan Ann O’Keefe, PhD, PT Curriculum Vitae Joan A. O’Keefe, PhD, PT Associate Professor Rush University Department of Cell & Molecular Medicine (formerly Anatomy and Cell Biology) 600 S. Paulina St. Suite 507 AcFac Chicago, Illinois 60612-33244 (312) 563-3940 (office phone) (312) 942-5744 (Fax) [email protected] Education 1981 B.S. in Physical Therapy (Magna Cum Laude); The University of Illinois - Chicago 1992 Ph.D. Cell Biology, Neurobiology and Anatomy; Loyola University of Chicago 1992 -1993 Postdoctoral Fellow; Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy/Sanders Brown Center on Aging; University of Kentucky; Mentor: Mark P. Mattson, PhD. Academic Appointments 2017- Associate Professor, Department of Cell & Molecular Medicine and Neurological Sciences, Rush University, Chicago, IL. 2018- Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Health Sciences, Rush University, Chicago, IL. 2009 - Assistant Professor, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Rush University College of Medicine, Chicago, IL. 2015- Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Health Sciences, Rush University, Chicago, IL. 2015- Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush University, Chicago, IL. 2014- Assistant Professor, Graduate College, Rush University. Joan Ann O’Keefe, PhD, PT 2008- 2009 Part Time Faculty Laboratory Instructor, Human Gross Anatomy for First Year Medical students in all blocks. Rush University Medical College, Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, Chicago, IL 1992 - 1996 Assistant Professor, Division of Physical Therapy, Department of Clinical Sciences, University of Kentucky Medical Center, Lexington, KY. 1993- 1996 Associate Member, Graduate Faculty, Physical Therapy Program, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY. 1992 - 1996 Core Faculty Member, Interdisciplinary Human Development Institute Leadership Development and Training Program; University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY. -

A Discussion of Goethe's Faust Part 1 Rafael Sordili, Concordia University

Sordili: Nothingness on the Move Sordili 1 Nothingness on the Move: A Discussion of Goethe's Faust Part 1 Rafael Sordili, Concordia University (Editor's note: Rafael Sordili's paper was selected for publication in the 2013 Agora because it was one of the best three presented at the ACTC Student Conference at Shimer College in Chicago in March 2013.) In the world inhabited by Faust, movement is a metaphysical fact: it is an expression of divine will over creation. There are, however, negative consequences to an existence governed by motion. The most prevalent of them is a feeling of nothingness and nihilism. This essay will discuss the relations between movement and such feelings in Goethe's Faust.1 It is my thesis that the assertion of his will to life, the acceptance of his own limitations, and the creation of new personal values are the tools that will ultimately enable Faust to escape nihilism. Metaphysics of Motion Faust lives in a world in which motion is the main force behind existence. During the Prologue in Heaven, three archangels give speeches in praise of the Creator, emphasizing how the world is in a constant state of movement. Raphael states that the movement of the Sun is a form of worship: "The sun proclaims its old devotion / [. .] / and still completes in thunderous motion / the circuits of its destined years" (246-248). For Gabriel, the rotation of the earth brings movement to all the elements upon its surface: "High cliffs stand deep in ocean weather, / wide foaming waves flood out and in, / and cliffs and seas rush on together / caught in the globe's unceasing spin" (251-258). -

Medical Education, Registration and £& «•^G**

Kentucky University Medical Department. 905) Indiana and University of Louisville.(1920) Kentucky Medical Education, Registration College of Physicians and Surgeons, Baltimore.(1909) W. Virginia Johns Hopkins University.(1919) Virginia Hospital Service Maryland Medical College.(1911) Pennsylvania, (1913) W. Virginia University of Maryland.(1889) New York, (1890) Maryland (1920) North Carolina St. Louis University.(1908) Illinois COMING EXAMINATIONS Washington University .(1912) Missouri Columbia University .'..(1915) New York Alabama: Montgomery, Jan. 10. Chairman, Dr. Samuel W. Welch, Leonard Medical School.(1911) Tennessee, (1912) Virginia Montgomery. Eclectic Medical College, Cincinnati.(1915) Ohio Arizona: Phoenix, Jan. 3-4. Sec, Dr. Ancil Martin, 207 Goodrich Jefferson Medical College.(1919) Delaware Bldg., Phoenix. University of Pennsylvania.(1898) Delaware Colorado: Denver, Jan. 3. Sec., Dr. David A. Strickler, 612 Empire Medical College of the State of South Carolina.(1907) S.Carolina Bldg., Denver. Meharry Medical College.(1911), (1916) Georgia District of Columbia: Washington, Jan. 10. Sec, Dr. Edgar P. (1917) North Carolina, (1920) Tennessee Copeland, 1315 Rhode Island Ave., Washington. University of Vermont.(1913) Vermont Hawaii: Honolulu, Jan. 9. Sec, Dr. G. C. Milnor, 401 Beretania St., College Year Endorsement Honolulu. endorsement of credentials Graci, with Illinois: Chicago, Jan. 10-12. Director, Mr. W. H. H. Miller, University of Maryland.(1914) Nat'l Bd. Med. Ex. Springfield. * Graduation not verified. Indiana: Indianapolis, Jan. 10. Sec, Dr. Wm. T. Gott, Crawfords- Yille. Minnesota: Minneapolis, Jan. 3-5. Sec, Dr. Thomas S. McDavitt, 539 Lowry Bldg., St. Paul. Kansas June Examination New Mexico: Santa Fe, Jan. 9-10. Sec, Dr. R. E. McBride, Las Cruces. Dr. Albert S. Ross, secretary, Kansas State Board of Med¬ New York: Albany, Buffalo. -

Rush Medical College Class of 2021

Excellence is just the beginning. Rush Medical College Postgraduate Appointments Class of 2021 Number Matched by Specialty & Institution PGY2 Appointments Only NUMBER MATCHED BY SPECIALTY AND INSTITUTION Anesthesiology Family Medicine 4 Rush University Med Ctr-IL 1 Advocate Health Care-IL 1 Vanderbilt Univ Med Ctr-TN 1 Boston Univ Med Ctr-MA 1 Kaiser Permanente-San Diego-CA Total: 5 1 MacNeal Hospital-IL Dermatology 1 Northwestern McGaw/NMH/VA-IL 1 Poudre Valley Hospital-CO 1 Med Coll Wisconsin Affil Hosps 1 Scripps Mercy Hosp-Chula Vista-CA 1 UPMC Medical Education-PA 1 U Arizona COM-South Campus Total: 2 1 U Rochester/Strong Memorial-NY 1 West Suburban Med Ctr-IL Emergency Medicine Total: 10 1 Alameda Health Sys-Highland Hosp-CA 1 Albert Einstein Med Ctr-PA 1 Cook County Health and Hosps Sys-IL 2 Harbor-UCLA Med Ctr-CA 1 HealthPartners Institute-MN 1 Montefiore Med Ctr/Einstein-NY 1 NYU Grossman School Of Medicine-NY 1 Rush University Med Ctr-IL 1 Spectrum Health Lakeland-MI 1 Trident Medical Center-SC 1 U Illinois COM-Chicago 1 U Washington Affil Hosps 1 U Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics 1 Univ of Chicago Med Ctr-IL 1 University of Utah Health Total: 16 All efforts for accuracy of this information were made by the OIME. Omission of any individual student's information was at the student's request. NUMBER MATCHED BY SPECIALTY AND INSTITUTION Internal Medicine Neurology 1 B I Deaconess Med Ctr-MA 1 Emory Univ SOM-GA 2 Cook County Health and Hosps Sys-IL 3 Rush University Med Ctr-IL 1 Harbor-UCLA Med Ctr-CA 1 University of Utah Health -

NURSEA Publication of the Kansas State Nurses Association January-February 2012 Nursing Advocacy

The Kansas NURSEA Publication of the Kansas State Nurses Association January-February 2012 Nursing Advocacy Centennial Celebration Oct. 11-13, Marriott Hotel, Wichita The Voice and Vision of Nursing in Kansas VOLUME 87 NUMBER 1 The Kansas The Kansas Nurse is the official publication of the Kansas State Nurses Association, 1109 SW Topeka Blvd., Topeka, Kansas 66612-1602; 785-233-8638. The journal is owned and published by the KSNA six times a year, in the odd months of the year. It is a peer re- viewed publication. The views and opinions expressed in the editorial and advertising material are those of the authors and adverstisers and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the KSNA, the Edito- rial Board members or the publisher, editors and staff of January-February 2012 Contents KSNA. Twelve dollars of every KSNA member’s dues is NURSE for an annual subscription to The Kansas Nurse. 3. From KSNA President Sandra Watchous, MN, RN Annual subscription is $50 domestic and $60 foreign. 4. From KSNA Executive Director Terry Leatherman It is indexed in the International Nursing Index and the 5. From KSNA Office Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. 6. 2012 KSNA Board of Directors It is available on National Archives Publishing Company, 7. 2012-2015 KSNA Delegates at Large to ANA and 2012 KSNA District Presidents Ann Arbor, MI 48106. The policy of the KSNA Editorial Board is to retain copyright privileges and control of ar- 8. 2012 KSNA Committee/Council Assignments ticles published in The Kansas Nurse when the articles 12. -

Nursing Heritage Foundation Collection, (K0247)

PRELIMINARY INVENTORY K0247 (KA0488, KA0584, KA0589, KA0603, KA0729, KA0817, KA0837, KA0883, KA0925, KA0974, KA1024, KA1132, KA1175) NURSING HERITAGE FOUNDATION COLLECTION This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center- Kansas City. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Introduction Approximately 112 cubic feet. The Nursing Heritage Foundation Collection consists of newsletters, journals, printed materials, organizational records, and other related items concerning various local, state, and national nursing associations. Additional topics include nursing education, historical associations, and affiliated interest groups. Also included are the personal papers of Laura Linebach, the historian for the Nursing Heritage Foundation. The Nursing Heritage Foundation was established in 1980 as a committee of the Missouri Nurses’ Association, District Two. By 1983, the foundation was incorporated into its own entity with the goal of preserving and recording nursing history as it relates to Missouri. Donor Information The collection was donated to the University of Missouri by the University of Missouri- Kansas City Miller Nichols Library on September 30, 1988 (Accession No. KA0488). An addition was made on June 20, 1990 by Laura Linebach on behalf of the Nursing Heritage Foundation (Accession No. KA0584). An addition was made on July 3, 1990 by Laura Linebach on behalf of the Nursing Heritage Foundation (Accession No. KA0589). An addition was made on September 14, 1990 by the Nursing Heritage Foundation (Accession No. KA0603). An addition was made on November 24, 1992 by Laura Linebach on behalf of the Nursing Heritage Foundation (Accession No. KA0729). An addition was made on June 21, 1994 by Laura Linebach on behalf of the Nursing Heritage Foundation (Accession No.