Youtube As a Site of Counternarratives to Transnormativity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MI5 NAMED EMPLOYER of the YEAR We Hear from Staff on the Changing Workplace Culture, and What This Success Means for LGBT Staff

FRIENDS MAGAZINE PUBLISHED FOR STONEWALL’S REGULAR DONORS SUMMER 2016 MI5 NAMED EMPLOYER OF THE YEAR We hear from staff on the changing workplace culture, and what this success means for LGBT staff. ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: GCHQ acknowledges historic mistreatment of LGBT people, Stonewall’s landmark conference on equality for disabled people, profi ling our international partners, and much more. Our Doors Are OpenTM. Our goal has never been to be the biggest rental car company. Only to be the best. But by embracing a diversity of people, talents and ideas, we are now both. Likewise, our doors will always be open, for all who share our drive to be the best. ©2015 Enterprise Rent-A-Car. G01841 11.15 CB FRIENDS | CONTENTS PAGE 4 WELCOME PAGE 6 ISLAM AND LGBT PAGE 5 OUT FOR CHANGE PAGE 7 SCHOOL ROLE MODEL VISITS CONTENTS FRIENDS MAGAZINE SUMMER 2016 PAGE 8 JUSTINE SMITHIES PAGE 12 MI5: EMPLOYER OF THE YEAR PAGE 15 GCHQ - WORKPLACE CONFERENCE PAGE 10 INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS PAGE 14 WEI: SOUTH WALES PAGE 16 LACE UP. CHANGE SPORT. PAGE 18 EQUALITY WALK 2016 PAGE 22 BI ROLE MODELS - PRIDE CALENDAR PAGE 20 BEN SMITH - 401 CHALLENGE PAGE 23 SUPPORTING STONEWALL Design by Alex Long, Stonewall. Printed on recycled FSC certifi ed paper, using fully sustainable, vegetable oil-based inks. All waste products are fully recycled. Registered in England and Wales: Stonewall Equality Ltd, Tower Building, York Road, London SE1 7NX. Registration no 02412299 - VAT no 862 9064 05 - Charity no 1101255 Summer 2016 Friends magazine 3 FRIENDS | WELCOME WELCOME Stonewall will stand by your side so that all lesbian, gay, bi and trans people are accepted without exception. -

Ove for Thought Pre-K & K

ove for thought Pre - K & K Integrated Physical Activities in the Early Learning Environment M ove for Thought Pre-K & K The Move for Thought Pre-K & K (M4T pre-K & K) was developed mainly for children (3-6 years old) in the preschool environment. However, all activities are developmentally appropriate for children in kindergarten classroom. Iowa Team Nutrition and the Iowa Department of Education would like to thank you for using the M4T pre-K & K program. The M4T pre-K & K program can be used to assist in: meeting physical activity needs, improving physical literacy and fundamental gross motor skills, developing the “whole child”, by practicing physical, cognitive, social, and emotional skills. The kit was developed by Spyridoula Vazou, PhD, Department of Kinesiology, Iowa State University. The activities and supporting files were developed by Dr. Vazou and Jacqueline Krogh, M.S., Department of Human Development & Family Studies, Iowa State University. Music was developed by Elizabeth Stegemöller, PhD, Department of Kinesiology, Iowa State University. Songs were adapted from “You and Me makes We” book by Elizabeth Schwartz. This project was funded by a Team Nutrition grant from the United States Department of Agriculture. Electronic copies of the kit and the music can be found at www.educateiowa.gov, under Team Nutrition. Suggested citation: Vazou, S., Krogh, J., & Stegemöller, E. (2015). Move for Thought Pre-K and K: Integrated physical activities in the early learning environment. Des Moines, IA: Iowa Department of Education. Federal Nondiscrimination Rights Statement In accordance with Federal law and U.S. Department of Agriculture policy, this institution is prohibited from discriminating on the basis of race, color national origin, sex, age, or disability. -

The Queer" Third Species": Tragicomedy in Contemporary

The Queer “Third Species”: Tragicomedy in Contemporary LGBTQ American Literature and Television A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Lindsey Kurz, B.A., M.A. March 2018 Committee Chair: Dr. Beth Ash Committee Members: Dr. Lisa Hogeland, Dr. Deborah Meem Abstract This dissertation focuses on the recent popularity of the tragicomedy as a genre for representing queer lives in late-twentieth and twenty-first century America. I argue that the tragicomedy allows for a nuanced portrayal of queer identity because it recognizes the systemic and personal “tragedies” faced by LGBTQ people (discrimination, inadequate legal protection, familial exile, the AIDS epidemic, et cetera), but also acknowledges that even in struggle, in real life and in art, there is humor and comedy. I contend that the contemporary tragicomedy works to depart from the dominant late-nineteenth and twentieth-century trope of queer people as either tragic figures (sick, suicidal, self-loathing) or comedic relief characters by showing complex characters that experience both tragedy and comedy and are themselves both serious and humorous. Building off Verna A. Foster’s 2004 book The Name and Nature of Tragicomedy, I argue that contemporary examples of the tragicomedy share generic characteristics with tragicomedies from previous eras (most notably the Renaissance and modern period), but have also evolved in important ways to work for queer authors. The contemporary tragicomedy, as used by queer authors, mixes comedy and tragedy throughout the text but ultimately ends in “comedy” (meaning the characters survive the tragedies in the text and are optimistic for the future). -

Ep #26: the Self Coaching Model Full Episode Transcript Brooke Castillo

Ep #26: The Self Coaching Model Full Episode Transcript With Your Host Brooke Castillo The Life Coach School Podcast with Brooke Castillo Welcome to The Life Coach School podcast, where it’s all about real clients, real problems, and real coaching. Now, your host, master coach instructor Brooke Castillo. Hey, everybody. What’s up? Welcome to the podcast. I’m stoked to be here today. I’m going to be talking to you guys about the model, self-coaching, the self-coaching model. I’m just really excited. I obviously have talked about the model all throughout all of the podcasts up to this point, but I wanted to do just one all- encompassing call about the model. Before I get started with that, before I do the overview and give you a taste of it, I want to make sure that you know that you can go to TheLifeCoachSchool.com/26 and download a visual of the model, so you can look at it as you’re going through this session. If you’re on your iPhone, like I usually am, you can just look at the artwork for this session. It has the model right there on there, on the artwork, so you can have a look. I think it really helps to see it visually. Before I get started, though, I want to address an email I got from Kara. I’m going to read you her email, and then I’m going to address it, because I think it goes along with what we’re going to be talking about in the model. -

Verizon up to Speed Live June 7, 2021 CART/CAPTIONING

Verizon Up to Speed Live June 7, 2021 CART/CAPTIONING PROVIDED BY: ALTERNATIVE COMMUNICATION SERVICES, LLC WWW.CAPTIONFAMILY.COM >> ANDY: HEY FRIENDS, HOPE YOU HAD A GREAT WEEKEND. HOPE YOU’RE FEELING GOOD - AND SPECIFICALLY - HOPE. YOU’RE FEELING GOOD ABOUT YOUR 5G KNOWLEDGE. THAT’S BECAUSE WE’VE GOT A FUN LIVE QUIZ ALL ABOUT 5G WITH PRIZES COMING UP IN JUST A FEW MINUTES. THE TOP FIVE FINISHERS TODAY ARE GETTING $50 VERIZON GIFTCARDS TO THE VERIZON BRAND STORE. I'D LIKE TO THINK WE'LL ALL BE WINNERS AFTER THIS QUIZ. WITH MORE KNOWLEDGE ABOUT 5G. THAT'S SO IMPORTANT IN CREATING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR OUR COLLECTIVE SUCCESS. AS WE WAIT FOR OUR CONTESTANTS TO ENTER SLIDO, OUR BIG PROMOTION LAST WEEK, THAT EVERYONE'S BEEN TALKING ABOUT. THE BIGGEST UPGRADE EVER, NEW AND EXISTING CUSTOMERS CAN UPGRADE TO A 5G PHONE ON US. WE'LL EVEN HELP COVER THE COST TO SWITCH WITH SELECT TRADE-IN AND UNLIMITED PLANS I WAS TOLD BY THE HIPPEST MEMBERS OF OUR TEAM THAT SOME WOULD DESCRIBE THIS UPGRADE AS A GLOW UP. I'LL BE HONEST, I WASN'T QUITE SURE WHAT THAT MEANT. LUCKY FOR ME, SINGER/SONG WRITER MEGHAN TRAINOR AGREED TO STOP BY AND HELP WITH MY GLOW-UP GAME. WE MADE A LITTLE GAME OUT OF IT. AFTER WE HEAR FROM MEGHAN, I'LL TELL YOU ANOTHER WAY TO WIN FANTASTIC GLOW-UP RELATED PRIZES. WITHOUT FURTHER ADIEU, HERE'S OUR CONVERSATION WITH MISS I'D WANT TO BE ME TOO, MEGHAN TRAINOR. >> OKAY, IT'S NOT EVERY DAY YOU HAVE A GRAMMY AWARD WINNING ARTIST ON UP TO SPEED, I WANT TO WELCOME MISS MEGHAN TRAINOR TO THE SHOW. -

Keeping up with the Psychoanalysts: Applying Lacanian and Feminist Theory to Reality Television

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Keeping Up with the Psychoanalysts: Applying Lacanian and Feminist Theory to Reality Television Catherine E. Leary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Leary, Catherine E., "Keeping Up with the Psychoanalysts: Applying Lacanian and Feminist Theory to Reality Television" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 249. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/249 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Keeping Up with the Psychoanalysts Applying Lacanian and Feminist Theory to Reality Television Catherine Leary University of Vermont Undergraduate Honors Thesis Film and Television Studies 2018 Committee Members Hyon Joo Yoo, Associate Professor, Film and Television Studies Anthony Magistrale, Professor, English Sarah Nilsen, Associate Professor, Film and Television Studies Leary 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Hyon Joo Yoo for her continued support and wealth of knowledge as my thesis supervisor as I worked my way through dense theory and panicked all year. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Tony Magistrale for serving as the chair of my committee and encouraging me to have fun and actually delve into a Kardashian based project. I also greatly appreciate Dr. Sarah Nilsen’s help as my third reader and as someone who isn’t afraid to challenge theoretical applications. -

Bachelorarbeit

BACHELORARBEIT Frau Michelle Kedmenec Die Kunst der Selbstinszenierung Eine Strukturanalyse des Reality-TV Formats Keeping up with the Kardashians 2017 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die Kunst der Selbstinszenierung Eine Strukturanalyse des Reality-TV Formats Keeping up with the Kardashians Autor/in: Frau Michelle Kedmenec Studiengang: Angewandte Medien Seminargruppe: AM14wM4-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Kersten Reininger Einreichung: Ort, Datum Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The art of self-staging A structural analysis of the reality TV show Keeping up with the Kardashians author: Ms. Michelle Kedmenec course of studies: Applied Media seminar group: AM14wM4-B first examiner: Prof. Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Kersten Reininger submission: Ort, Datum Bibliografische Angaben Kedmenec, Michelle: Die Kunst der Selbstinszenierung – Eine Strukturanalyse des Reality-TV Formats Kee- ping up with the Kardashians The art of self-staging – A structural analysis of the reality TV show Keeping up with the Kardashians 104 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2017 Abstract Das Thema der Forschungsarbeit lautet „Die Kunst der Selbstinszenierung – Eine Strukturanalyse der Reality-TV Formats Keeping up with the Kardashians“. Ziel dieser war es, das sogenannte Kardashian-Phänomen genauer zu untersuchen, um die Er- folgsfaktoren des Formates zu bestimmen. Die strukturelle Detailbetrachtung wurde mit Hilfe des Formats selbst, sowie mit zeitgenössischer Fachliteratur durchgeführt. -

A Film by Chris Moukarbel and Valerie Veatch Me @The Zoo a Film by Chris Moukarbel and Valerie Veatch

ME @THE ZOO A FILM BY CHRIS MOUKARBEL AND VALERIE VEATCH ME @THE ZOO A FILM BY CHRIS MOUKARBEL AND VALERIE VEATCH ME @THE ZOO tells the story of Chris Crocker, a video blogger from a small town in Tennessee. Crocker is part of the first generation of kids raised on the Internet, coming of age under constant self- surveillance. His online videos, including the infamous YouTube declaration “Leave Britney Alone!”– have been viewed hundreds of millions of times and have created a worldwide phenomenon. This portrait weaves a tapestry of Internet media with reactions from Crocker fans and haters to examine a new controversial kind of fame: the Internet folk hero. ACQUIRED BY HBO (USA) AND BBC (UK) DIRECTOR’S WORD Like so many others, we first discovered Chris Crocker by being sent early online videos such as “Bitch Please” and “This or That”. The first question we asked was apparently a common one. “Is this real?” Years later we began making a film that asked the same question in a more general sense. We began a documentary about the history and impact of reality televi- sion. As ideas of consciousness shift in lockstep with new technology, “Reality” has become the dominant medium. Our film research took us around the world. We interviewed everyone from the cast of the original Dutch reality show, Hollywood executives and even a Reality TV School. In the end, this hunt for reality brought us to a small town in Tennessee and to Chris Crocker. Crocker was raised in the age of reality where anyone with a camera can become a star. -

A.S. Election Results Announced MEET the NEW A.S

Volume 148, Issue 32 www.sjsunews.com/spartan_daily Tuesday, April 18, 2017 SPARTAN DAILY SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 WEEKLY WEATHER WIRE SPRING FOOTBALL See full story on page 8 TUES WED THURS FRI 68|51 67|51 69|49 77|52 chance rain mostly sunny mostly sunny sunny Information from weather.gov FOLLOW US! @SpartanDaily @spartandaily/spartandaily /spartandailyYT STUDENT GOVERNMENT A.S. election results announced MEET THE NEW A.S. GOVERNMENT BODY A.S. President: Ariadna Manzo A.S. Vice President: Cristina Cortes A.S. Controller: Joshua Villanueva A.S. Director of Business Affairs: SATVIR SAINI | SPARTAN DAILY Malik Akil The Associated Students election winners were announced at the results party held in Student Union Meeting Room 4. A.S. Director of Communications: Nayeli Lopez BY SATVIR SAINI last. As Briones announced and Cortes was the director of Staff Writer the winners, they each stepped Business Affairs. A.S. Director of Co-curricular Affairs: forward and stood next to the Those who are new to the Board Andrew Lingao Associated Students election congratulations banner. of Directors are looking forward to A.S. Director of Community and results were announced Thursday “I am honored to be the next being a part of the team. Sustainability Affairs: Tessa Mendes April 13. Ariadna Manzo was voted president for the school year,” “I ran for this position last election A.S. Director of External Affairs: the next A.S. president, along with Manzo said. “The time is now and I and didn’t get it,” Gill said. “This time Oladotun Hospidales Cristina Cortes as vice president cannot wait to work with the board I am very honored to be the director of A.S. -

Download Artifact

Unintentional Dialogues on YouTube 1 Running Head: UNINTENTIONAL DIALOGUES ON YOUTUBE Unintentional Dialogues on YouTube RESEV 554: Semester Project Analysis Memo Laura Bestler Iowa State University December 15, 2008 Unintentional Dialogues on YouTube 2 Introduction The purpose of this video is to illustrate themes within the online user commentary reacting to Chris Crocker’s (2008) YouTube video titled, “Gay HATE on YouTube!” The central question of this study is how users intermittently engage about Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Queer Questioning (LGTBQQ) topics represented on YouTube. The unintentional dialogues between users on YouTube™ are providing additional knowledge to what is happening within today’s society (Noblit, Flores, & Murillo, 2004). Online social networks are a natural place to employ post modern theory due to its playfulness, reflexivity, and the deconstruction of the cyber world (Noblit, Flores, & Murillo, 2004). The research findings demonstrate a connection between time and negative user reactions towards LGBTQQ topics. Why Online? An evolution of the online world has taken place to provide everyone the ability to create content. Social networks provided a way people to connect with friends, family and online social acquaintances. Similar to the offline world, user created content had begun to utilize hate language and expletives to describe people. These degrading interactions provided a catalyst for me to take action. This online social laboratory can be brought to light, deconstructed and transcended. Therefore, helping people understand their actions are broader than snippet commented online. These unintentional dialogues are broadcast around the world. The internet is an environment where people’s small gestures may become large, and it is a mirror or lens of the world around them (Popkin, 2008). -

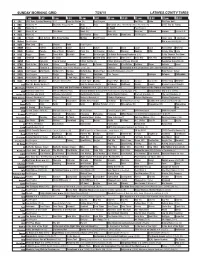

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

Ep #35: This Is Just the Beginning Full Episode Transcript Diana Murphy

Ep #35: This Is Just the Beginning Full Episode Transcript With Your Host Diana Murphy Weight Loss for CEOs with Diana Murphy Ep #35: This Is Just the Beginning Welcome to Weight Loss for CEOs. A podcast that teaches executives and leaders how to deal with the unique challenges of achieving sustainable weight loss while balancing the responsibility of a growing company, family, and their own health. Here's your host, executive coach, Diana Murphy. I have a surprising announcement today. This will be my last podcast that I produce for Weight Loss for CEOs, maybe for a while, and maybe forever. But don’t worry, you aren’t losing the support of my work in your life at all. And I want to tell you, this was not an easy decision. I love this podcast and I love serving you as a listener. But I have decided to stop production to focus my energies in a way that gives back more to my clients, and to my life, I think. I created this beautiful show for current and future clients, and it’s a fabulous resource. I’ll continue using it in that way going forward. But now that I’ve created over 70 episodes and have covered almost every topic, it came to a point that this was best for my business. The decision was not easy. In fact, it made me a little sad. But, like you, I am the CEO of my business and my life and I need to manage not only my financial resources, but the time invested and the energy and the creative energy I was spending.