Functional and Stylistic Features of Sports Announcer Talk: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEN's SOCCER 2019 Record Book

2019 Record Book MEN’S SOCCER Men's Soccer Record Book @ClemsonMSoccer 2019 CLEMSON SOCCER National Champions: 1984, 1987 • 14 ACC Championships 1 Single Match Records MEN’S SOCCER MOST GOALS SCORED BY A CLEMSON PLAYER 3 Gary Conner H-Mercer 9-5-84 No. Name Site-Opp. Date 3 Gary Conner H-Charleston 9-1-85 1. 7# Nnamdi Nwokocha H- Belmont Abbey 9-9-79 3 Paul Carollo A-North Carolina 9-15-85 2. 6 Henry Abadi A-Western Carolina 9-26-73 3 Eric Eichmann H-Winthrop 9-29-85 3. 5 Leo Serrano H- Erskine 10-10-67 3 Bruce Murray H-USC-Spar. 10-16-85 5 Andy Demori A-Emory 10-10-70 3 Eric Eichmann H-Charleston 8-31-86 5 Nabeel Kammoun A-Jacksonville 9-25-71 3 Jamey Rootes H-UNC-Asheville 9-1-87 5 Joe Babashak H-Furman 11-10-71 3 Kevin England H-Jacksonville 9-24-89 5 Henry Abadi A- N.C. State 9-16-73 3 Pearse Tormey H-Catawba 9-12-90 5 Christian Nwokocha H- Duke 10-26-75 3 Imad Baba H-Char. Southern 9-6-93 5 Wolde Harris H-Vanderbilt 9-4-94 3 Rivers Guthrie H-Mercer 9-14-94 10. 4 Andy Demori A-Emory 9-28-68 3 Danny Care H-The Citadel 9-20-95 4 Andy Demori A-The Citadel 10-26-68 3 Imad Baba H-Wofford 11-1-95 4 Henry Abadi H-Furman 10-3-73 3 Mark Lisi H-Erskine 10-16-96 4 Woolley Ford H-Furman 10-3-73 3 Scott Bower H-Belmont 9-9-98 4 Rennie Phillips A-N.C. -

Wake Forest Midfielder Sam Cronin Wins National Balloting As 2008 Lowe’S Senior Class Award Recipient for Men’S Soccer

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 12, 2008 WAKE FOREST MIDFIELDER SAM CRONIN WINS NATIONAL BALLOTING AS 2008 LOWE’S SENIOR CLASS AWARD RECIPIENT FOR MEN’S SOCCER Nation’s Premier Award for Seniors Presented at NCAA® Men’s College Cup® (Frisco, TX) – Two-year Wake Forest team captain Sam Cronin – leader of the country’s top- ranked men’s soccer team, high-achieving student and active community citizen – has been selected as the 2008 Lowe’s Senior CLASS Award winner in the men’s soccer division. The award, chosen by a nationwide vote of coaches, media and fans, is presented annually to the most outstanding NCAA Division I senior student-athlete in nine sports. The announcement and trophy presentation were made today by Lowe’s executives during halftime of the second semi-finals game of the NCAA Men’s College Cup in Frisco, Texas. This marks the second year for the men’s soccer division of the Lowe’s Senior CLASS Award. Evan Barnes of the United States Naval Academy was the inaugural winner in 2007. An acronym for Celebrating Loyalty and Achievement for Staying in School, the Lowe’s Senior CLASS Award has grown into the nation’s premier tribute to college seniors. The award identifies personal qualities that define a complete student-athlete, with criteria including excellence in the classroom, character and community, as well as competition on the field. “It’s a great honor to receive the Lowe's Senior CLASS Award,” Cronin said. “To see the attention it has received from the community really makes this award special. -

Rodney Rogers Features

FROM THE HILLS OF HARLAN | “UH-OH!” | KATHY “KILLIAN” NOE (’80): LIVING IN A BROKEN WORLD SPRING 2017 RODNEY ROGERS FEATURES 46 HERE’S TO THE KING By Kerry M. King (’85) and Albert R. Hunt (’65, Lit.D. ’91, P ’11) Success and fame didn’t change Arnold Palmer (’51, LL.D. ’70), king of golf and chief goodwill ambassador for his alma mater. 2 34 THREADS OF GRACE LIVING IN A BROKEN WORLD By Cherin C. Poovey (P ’08) By Steve Duin (’76, MA ’79) Eight years after a life-threatening accident, Kathy “Killian” Noe (’80) has spent her basketball legend Rodney Rogers (’94) life finding gifts amid the brokenness, maintains his courage and hope — and blessing abandoned souls among us. inspires others to find theirs. 14 88 FROM THE HILLS OF HARLAN CONSTANT & TRUE By Tommy Tomlinson By Julie Dunlop (’95) A character in the best sense of the word, Breathtaking: return to campus after Robert Gipe (’85) sits back, listens and 20 years brings tears of joy, amazement elevates the voices of Appalachia. and gratitude. 28 DEPARTMENTS “UH-OH!” 60 Around the Quad By Maria Henson (’82) 62 Philanthropy A toddler upends the Trolley Problem, leaving his father the professor to watch 64 Class Notes the video go viral. WAKEFOREST MAGAZINE the first issue of Wake Forest Magazine in 2017 honors a number of SPRING 2017 | VOLUME 64 | NUMBER 2 inspirational Demon Deacons and celebrates the accomplishments of the Wake Will campaign. ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT AND EDITOR-AT-LARGE The tributes for the late, beloved Demon Deacon Arnold Palmer show how much Maria Henson (’82) he meant to so many. -

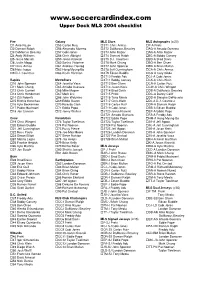

Upper Deck Major League MLS 2004

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2004 checklist Fire Galaxy MLS Stars MLS Autographs (x/20) 1 Ante Razov 55 Carlos Ruiz ST1 Chris Armas P-A Preki 2 Damani Ralph 56 Alejandro Moreno ST2 DaMarcus Beasley AG-A Amado Guevara 3 DaMarcus Beasley 57 Cobi Jones ST3 Ante Razov AR-A Ante Razov 4 Andy Williams 58 Chris Albright ST4 Damani Ralph BC-A Bobby Convey 5 Jesse Marsch 59 Jovan Kirovski ST5 D.J. Countess BD-A Brad Davis 6 Justin Mapp 60 Sasha Victorine ST6 Mark Chung BO-A Ben Olsen 7 Chris Armas 61 Andreas Herzog ST7 John Spencer BR-A Brian Mullan 8 Nate Jaqua 62 Hong Myung-Bo ST8 Jeff Cunningham CA-A Chris Armas 9 D.J. Countess 63 Kevin Hartman ST9 Edson Buddle CG-A Cory Gibbs ST10 Freddy Adu CJ-A Cobi Jones Rapids MetroStars ST11 Bobby Convey CK-A Chris Klein 10 John Spencer 64 Joselito Vaca ST12 Ben Olsen CR-A Carlos Ruiz 11 Mark Chung 65 Amado Guevara ST13 Jason Kreis CW-A Chris Wingert 12 Chris Carrieri 66 Mike Magee ST14 Brad Davis DB-A DaMarcus Beasley 13 Chris Henderson 67 Mark Lisi ST15 Preki DC-A Danny Califf 14 Zizi Roberts 68 John Wolyniec ST16 Tony Meola DD-A Dwayne DeRosario 15 Ritchie Kotschau 69 Eddie Gaven ST17 Chris Klein DJ-A D.J. Countess 16 Kyle Beckerman 70 Ricardo Clark ST18 Carlos Ruiz DR-A Damani Ralph 17 Pablo Mastroeni 71 Eddie Pope ST19 Cobi Jones EB-A Edson Buddle 18 Joe Cannon 72 Jonny Walker ST20 Jovan Kirovski EP-A Eddie Pope ST21 Amado Guevara FA-A Freddy Adu Crew Revolution ST22 Eddie Pope HM-A Hong Myung-Bo 19 Chris Wingert 73 Taylor Twellman ST23 Taylor Twellman JA-A Jeff Agoos 20 Edson Buddle 74 -

Congressional Record—House H6449

July 29, 2010 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H6449 Gospel Music Heritage Month, and I California, Michael Bradley of Manhattan I rise today in support of H. Res. 1527, Con- yield back the balance of my time. Beach, California, Oguchi Onyewu of Olney, gratulating the United States Men’s National The SPEAKER pro tempore. The Maryland, Steve Cherundolo of San Diego, Soccer Team for its inspiring performance in question is on the motion offered by California, DaMarcus Beasley of Ft. Wayne, the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Indiana, Clint Dempsey of Nacogdoches, Mr. Speaker, it is with great honor that I the gentlewoman from California (Ms. Texas, Herculez Gomez of Las Vegas, Ne- CHU) that the House suspend the rules vada, Landon Donovan of Redlands, Cali- stand before this body to commend the U.S. and pass the joint resolution, H.J. Res. fornia, Stuart Holden of Houston, Texas, Men’s National Soccer Team on their truly 90. Jonathan Bornstein of Los Alamitos, Cali- amazing performance in this year’s FIFA The question was taken; and (two- fornia, Ricardo Clark of Jonesboro, Georgia, World Cup. thirds being in the affirmative) the Edson Buddle of New Rochelle, New York, I would also like to commend my distin- rules were suspended and the joint res- Jay DeMerit of Green Bay, Wisconsin, Jose´ guished colleague from Texas, Mr. GOHMERT, olution was passed. Torres of Longview, Texas, Jozy Altidore of for introducing this resolution that recognizes Boca Raton, Florida, Brad Guzan of Homer A motion to reconsider was laid on the men who represented our Nation on soc- Glen, Illinois, Maurice Edu of Fontana, Cali- cer’s grandest stage. -

Upper Deck Major League MLS 2005

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2005 checklist Fire Revolution MLS Goal Men MLSignatures (x/25) 1 Tony Sanneh 59 Pat Noonan GM1 Justin Mapp AE-S Alecko Eskandarian 2 Ante Razov (Crew) 60 Taylor Twellman GM2 Joe Cannon AG-S Amado Guevara 3 Andy Herron 61 Steve Ralston GM3 Edson Buddle AR-S Ante Razov 4 Chris Armas 62 Andy Dorman GM4 Jon Busch BC-S Brian Ching 5 Kelly Gray 63 Jose Cancela GM5 Eddie Johnson BM-S Brian Mullan 6 Nate Jaqua 64 Clint Dempsey GM6 Freddy Adu CA-S Chris Armas 7 Justin Mapp 65 Matt Reis GM7 Jaime Moreno CD-S Clint Dempsey 66 Jay Heaps GM8 Josh Wolff CJ-S Cobi Jones Rapids GM9 Nick Rimando CR-S Carlos Ruiz 8 Joe Cannon Earthquakes GM10 Davy Arnaud DA-S Davy Arnaud 9 Pablo Mastroeni 67 Craig Waibel GM11 Carlos Ruiz DK-S Dema Kovalenko 10 Landon Donovan (Galaxy) 68 Ryan Cochrane GM12 Amado Guevara EB-S Edson Buddle 11 Jean Philippe Peguero 69 Pat Onstad GM13 Pat Noonan EG-S Eddie Gaven 12 Mark Chung 70 Brian Ching GM14 Taylor Twellman EP-S Eddie Pope 13 Jordan Cila 71 Brian Mullan GM15 Pat Onstad FA-S Freddy Adu 14 Chris Henderson 72 Dwayne De Rosario GM16 Brian Ching JA-S Jonny Walker 73 Troy Dayak GM17 Ante Razov JB-S Jon Busch Crew 74 Eddie Robinson GM18 Jeff Cunningham JC-S Joe Cannon 15 Edson Buddle JG-S Jeff Agoos 16 Jon Busch CD Chivas USA MLS Jersey JK-S Jason Kreis 17 Jeff Cunningham (Rapids) 75 Arturo Torres BC-J Brian Ching JM-S Justin Mapp 18 Ross Paule 76 Orlando Perez CA-J Chris Armas JO-S Jaime Moreno 19 Klye Martino 77 Ezra Hendrickson CR-J Carlos Ruiz JP-S Jean Philippe Peguero 20 Simon Elliott -

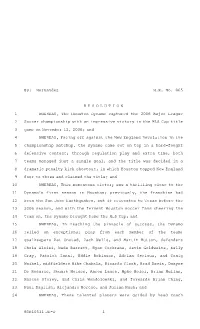

Salsa2bills 1..2

By:AAHernandez H.R.ANo.A865 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, The Houston Dynamo captured the 2006 Major League 2 Soccer championship with an impressive victory in the MLS Cup title 3 game on November 12, 2006; and 4 WHEREAS, Facing off against the New England Revolution in the 5 championship matchup, the Dynamo came out on top in a hard-fought 6 defensive contest; through regulation play and extra time, both 7 teams managed just a single goal, and the title was decided in a 8 dramatic penalty kick shootout, in which Houston topped New England 9 four to three and claimed the title; and 10 WHEREAS, This momentous victory was a thrilling close to the 11 Dynamo 's first season in Houston; previously, the franchise had 12 been the San Jose Earthquakes, but it relocated to Texas before the 13 2006 season, and with the fervent Houston soccer fans cheering the 14 team on, the Dynamo brought home the MLS Cup; and 15 WHEREAS, In reaching the pinnacle of success, the Dynamo 16 relied on exceptional play from each member of the team: 17 goalkeepers Pat Onstad, Zach Wells, and Martin Hutton, defenders 18 Chris Aloisi, Wade Barrett, Ryan Cochrane, Kevin Goldwaite, Kelly 19 Gray, Patrick Ianni, Eddie Robinson, Adrian Serioux, and Craig 20 Waibel, midfielders Mike Chabala, Ricardo Clark, Brad Davis, Dwayne 21 De Rosario, Stuart Holden, Aaron Lanes, Mpho Moloi, Brian Mullan, 22 Marcus Storey, and Chris Wondolowski, and forwards Brian Ching, 23 Paul Daglish, Alejandro Moreno, and Julian Nash; and 24 WHEREAS, These talented players were guided by head coach 80R10511 -

General Assembly of North Carolina Session 2007 H D House Joint Resolution Drhjr30718-Lg-639 (3/24)

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2007 H D HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION DRHJR30718-LG-639 (3/24) Sponsors: Representatives Glazier, McGee, Folwell, and Parmon (Primary Sponsors). Referred to: 1 A JOINT RESOLUTION HONORING THE MEN'S SOCCER TEAM AT WAKE 2 FOREST UNIVERSITY ON WINNING A NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP. 3 Whereas, on December 16, 2007, the men's soccer team at Wake Forest 4 University won the National Collegiate Athletic Association's (NCAA) College Cup 5 Title, defeating Ohio State by a score of 2-1; and 6 Whereas, this achievement gave Wake Forest University its first NCAA 7 men's soccer national championship title; and 8 Whereas, the men's soccer team finished its 2007 Atlantic Coast Conference 9 (ACC) season with a record of 6-1-1 and an overall record of 22-2-2, the best in school 10 history; and 11 Whereas, many individual team members were recognized for their efforts 12 during the year including, Marcus Tracy, who was named the NCAA tournament's Most 13 Valuable Offensive Player, and Brian Edwards, who was named the NCAA 14 tournament's Most Valuable Defensive Player; and 15 Whereas, Cody Amoux, Pat Phelan, and Sam Cronin were named 16 All-Americans by the National Soccer Coaches Association of America (NSCAA); and 17 Whereas, Corben Bone was named the ACC's Freshman of the Year and 18 selected to the First Team All-Freshman squad by Soccer America along with 19 teammate, Ike Opara; and 20 Whereas, Pat Phelan and Julian Valentin were selected to play for the U.S. -

Upper Deck MLS 2010 Checklist

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2010 checklist Fire Dallas FC Red Bulls Toronto FC □1 Mike Banner □58 Jeff Cunningham □113 Juan Pablo Angel □164 Nana Attakora □2 John Thorrington □59 Kyle Davies □114 Danleigh Borman □165 Chad Barrett □3 Jon Busch □60 David Ferreira □115 Andrew Boyens □166 Jim Brennan □4 Calen Carr □61 Atiba Harris □116 Kevin Goldthwaite □167 Sam Cronin □5 Wilman Conde □62 Daniel Hernandez □117 Greg Sutton □168 Dwayne De Rosario □6 Peter Lowry □63 Ugo Ihemelu □118 Jeremy Hall □169 Julian de Guzman □7 Justin Mapp □64 Dax McCarty □119 Macoumba Kandji □170 Stefan Frei □8 Brian McBride □65 Heath Pearce □120 Dane Richards □171 Ali Gerba □9 Patrick Nyarko □66 Dario Sala □121 Seth Stammler □172 Nick Garcia □10 Marko Pappa □67 Brek Shea □122 John Wolyniec □173 Carl Robinson □11 Logan Pause □68 Dave van den Bergh □174 O'Brian White □12 Dasan Robinson Union □175 Marvell Wynne Dynamo □123 Fred Chivas □69 Corey Ashe □124 Jordan Harvey Super Draft 2010 □13 Jonathan Bornstein □70 Geoff Cameron □125 Andrew Jacobson □176 Danny Mwanga ( Union) □14 Justin Braun □71 Mike Chabala □126 Sebastien Le Toux □177 Tony Tchani (Red Bulls) □15 Chukwudi Chijindu □72 Brian Ching □127 Alejandro Moreno □178 Ike Opara (Earthquakes) □16 Jorge Flores □73 Brad Davis □128 Shea Salinas □179 Teal Bunbury (Wizards) □17 Maykel Galindo □74 Bobby Boswell □129 Chris Seitz □180 Zach Loyd (FC Dallas) □18 Ante Jazic □75 Luis Angel Landin □130 Nick Zimmerman □181 Amobi Okugo ( Union) □19 Sacha Kljestan □76 Brian Mullan □182 Jack McInerney ( Union) □20 Gerson Mayen -

2021 MLS Standings and Leaders Includes Games of Sunday, May 02, 2021 OVERALL HOME ROAD

2021 MLS Standings and Leaders Includes games of Sunday, May 02, 2021 OVERALL HOME ROAD East GP W L T PTS GF GA GD W L T GF GA W L T GF GA New England Revolution 3 2 0 1 7 5 3 2 2 0 0 3 1 0 0 1 2 2 New York City FC 3 2 1 0 6 8 2 6 1 0 0 5 0 1 1 0 3 2 Orlando City SC 3 1 0 2 5 4 1 3 1 0 1 3 0 0 0 1 1 1 CF Montreal 3 1 0 2 5 6 4 2 1 0 1 4 2 0 0 1 2 2 Atlanta United 3 1 1 1 4 4 3 1 1 0 0 3 1 0 1 1 1 2 Inter Miami CF 3 1 1 1 4 4 4 0 0 1 0 2 3 1 0 1 2 1 New York Red Bulls 3 1 2 0 3 5 5 0 1 1 0 3 2 0 1 0 2 3 D.C. United 3 1 2 0 3 3 6 -3 1 0 0 2 1 0 2 0 1 5 Nashville SC 3 0 0 3 3 4 4 0 0 0 3 4 4 0 0 0 0 0 Columbus Crew SC 2 0 0 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 Toronto FC 2 0 1 1 1 4 6 -2 0 0 1 2 2 0 1 0 2 4 Philadelphia Union 3 0 2 1 1 1 4 -3 0 2 0 1 4 0 0 1 0 0 Chicago Fire 3 0 2 1 1 3 7 -4 0 0 1 2 2 0 2 0 1 5 FC Cincinnati 3 0 2 1 1 2 10 -8 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 2 10 West GP W L T PTS GF GA GD W L T GF GA W L T GF GA Seattle Sounders FC 3 2 0 1 7 8 1 7 2 0 0 7 0 0 0 1 1 1 San Jose Earthquakes 3 2 1 0 6 8 4 4 2 0 0 7 2 0 1 0 1 2 Real Salt Lake 2 2 0 0 6 5 2 3 1 0 0 3 1 1 0 0 2 1 Austin FC 3 2 1 0 6 4 3 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 0 4 3 LA Galaxy 3 2 1 0 6 6 7 -1 1 0 0 3 2 1 1 0 3 5 Los Angeles FC 3 1 0 2 5 4 2 2 1 0 1 3 1 0 0 1 1 1 FC Dallas 3 1 1 1 4 5 4 1 1 0 1 4 1 0 1 0 1 3 Houston Dynamo 3 1 1 1 4 4 4 0 1 0 1 3 2 0 1 0 1 2 Vancouver Whitecaps FC 3 1 1 1 4 3 3 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 2 2 Sporting Kansas City 3 1 1 1 4 4 5 -1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 3 4 Colorado Rapids 3 1 1 1 4 2 3 -1 0 1 0 1 3 1 0 1 1 0 Portland Timbers 3 1 2 0 3 3 6 -3 1 0 0 2 1 0 2 0 1 5 Minnesota United -

Buy Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys

Buy Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps Online Save 70% Off,Free Shipping We Are One Of The Jerseys Wholesaler.To have an opinion on Brandon Marshall,custom nfl jersey,your family significantly better be a multi function coach or perhaps an all in one Hall concerning Famer. Nobody else is qualified, apparently. [+] EnlargeAP Photo/J Pat CarterBrandon Marshall had 10 receptions as well as for 166 yards and a multi function touchdown Sunday against going to be the Jets.On going to be the latest edition relating to the NFL Network's "Playbook,this is because analysts Sterling Sharpe, Mike Mayock and Solomon Wilcots criticized Marshall along with fading at going to be the stop having to do with Sunday night's 31-23 new ones mishaps to the New York Jets. Marshall responded Thursday by essentially saying going to be the analysts are do not qualified to understand more about scrutinize him "Those guys are players,flag football jerseys, former players,authentic nba jerseys cheap,the excuse is Marshall said. "They at no time coached. So they are going to want to continue for more information regarding need to panic about what they should best of the best and all is not lost about a number of other enough detailed information online that they don't are aware of that anything about.graphs Marshall later added: "What any of those guys are saying, that's just them trying to explore a robust in line with the and an effective like they know what they're talking about. -

New England Revolution Game Notes May 13, 2006 at 7 P.M

REVOLUTION VS. CD CHIVAS USA -- SATURDAY, MAY 13, 2006 -- 7 P.M. ET PAGE 1 NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION GAME NOTES MAY 13, 2006 AT 7 P.M. ET 2006 REVOLUTION SCHEDULE OVERALL RECORD: 2-2-1 HOME: 1-1-0 AWAY: 1-1-1 DATE OPPONENT TIME/RESULT TV Sat., April 1 at Los Angeles Galaxy W 1-0 ESPN2 Sat., April 8 at New York Red Bulls T 0-0 WB56 Sat., April 15 at Kansas City Wizards L 0-1 WB56 EW NGLAND VS HIVAS N E . CD C USA Sun., April 30 CHICAGO FIRE L 1-2 WB56 (2-2-1, 7 PTS.) (1-2-1, 4 PTS.) Sat., May 6 LOS ANGELES GALAXY W 4-0 ESPN2 Sat., May 13 CD CHIVAS USA 7:00 PM FSN Sat., May 20 at FC Dallas 8:30 PM WB56 ATCH NFORMATION Sat., May 27 HOUSTON DYNAMO 7:30 PM FSN M I Sat., June 3 at D.C. United 7:30 PM WB56 Date: Saturday, May 13, 2006 Time: 7 p.m. ET Sun., June 11 at Chicago Fire 7:00 PM FSN Location: Gillette Stadium, Foxborough, Mass. Sat., June 17 D.C. UNITED 6:00 PM FSN Wed., June 21 at Columbus Crew 7:30 PM FSN TV: FSN (Brad Feldman – play-by-play, Greg Lalas – analyst) Sat., June 24 at Real Salt Lake 9:00 PM FSN Satellite Information: KU BAND SBS 6 Tr. 11A Upper, Uplink: Wed., June 28 FC DALLAS 7:30 PM FSN 14271(V), Downlink: 11971(H), Symbol Rate: 6.1113 Sat., July 1 NEW YORK RED BULLS 6:00 PM ESPN2 Radio: WRKO 680 AM Tues., July 4 at Colorado Rapids 9:30 PM FSN Spanish Radio: WJDA 1300 AM (Pedro Rosalez – play-by-play, Sat., July 8 at Chicago Fire 8:30 PM WB56 Marino Velasquez – analyst, Baltazar Palencia – sideline) Fri., July 14 REAL SALT LAKE 7:30 PM FSN Referee: Mark Geiger Wed., July 19 at Kansas City Wizards 8:30 PM FSN Referee's Assistants: Paul Scott, CJ Morgante Sat., July 22 at Houston Dynamo 8:30 PM WB56 Fourth Official: Erich Simmons Wed., July 26 D.C.