Land, Livelihoods and Housing Programme 2015-18 Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A74 City of Whk Annual Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABREVIATIONS 4 COUNCIL STRUCTURE 2017/18 5 OFFICE OF THE CEO 3 CITY POLICE (CIP) 51 MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR 6 Theme 1: Governance 51 Public Safety and Security - Crime Rate 51 MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE Public Safety and Security - Road Safety 53 OFFICER 10 Public Safety and Security - Dedicated Municipal Court 55 OVERVIEW OF WINDHOEK 14 Public Safety and Security - By-laws 55 GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION AND POPULATION 15 City Police: Funding Secured from Central City of Windhoek Political and Government 56 Socio-Economic Profle 15 Priorities for 2018/2019 56 Population Trends and Urbanisation 16 Environmental 17 URBAN AND TRANSPORT PLANNING (UTP) 58 Poverty Levels 17 Theme 1: Financial Sustainability 58 Building Plan Approval 58 INTRODUCTION 22 Land-use Management - Town Planning STRATEGIC INTENT 22 Applications 59 Vision Statement 23 Priorities for 2018/2019 60 Mission Statement 24 Values 24 STRATEGIC FUNDING (PUBLIC TRANSPORT) 60 Strategic Objectives 24 heme 1: Financial Sustainability 60 Key Performance Areas 24 Strategic Funding ( Public Transport - Key Performance Indicators 24 Acquisition of Busses) 60 Targets 25 Theme 2: Social Progression, Economic Corporate Scorecard 25 Advancement and infrastructure Council and Management Structure 30 Development 62 Public Transportation 62 ORGANISATIONAL OVERVIEW 31 Priorities for 2019/2019 63 Local Authorities Act (Act 23, 1992) 31 Update of Laws Exercise 34 ELECTRICITY (ELE) 65 Theme 1: Financial Sustainability 65 DEPARTMENTAL PERFORMANCE REPORTS 35 Strategic Funding (Electrifcation) -

Public Perception of Windhoek's Drinking Water and Its Sustainable

Public Perception of Windhoek’s Drinking Water and its Sustainable Future A detailed analysis of the public perception of water reclamation in Windhoek, Namibia By: Michael Boucher Tayeisha Jackson Isabella Mendoza Kelsey Snyder IQP: ULB-NAM1 Division: 41 PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF WINDHOEK’S DRINKING WATER AND ITS SUSTAINABLE FUTURE A DETAILED ANALYSIS OF THE PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF WATER RECLAMATION IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA AN INTERACTIVE QUALIFYING PROJECT REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE SPONSORING AGENCY: Department of Infrastructure, Water and Waste Management The City of Windhoek SUBMITTED TO: On-Site Liaison: Ferdi Brinkman, Chief Engineer Project Advisor: Ulrike Brisson, WPI Professor Project Co-advisor: Ingrid Shockey, WPI Professor SUBMITTED BY: ____________________________ Michael Boucher ____________________________ Tayeisha Jackson ____________________________ Isabella Mendoza ____________________________ Kelsey Snyder Abstract Due to ongoing water shortages and a swiftly growing population, the City of Windhoek must assess its water system for future demand. Our goal was to follow up on a previous study to determine the public perception of the treatment process and the water quality. The broader sample portrayed a lack of awareness of this process and its end product. We recommend the City of Windhoek develop educational campaigns that inform its citizens about the water reclamation process and its benefits. i Executive Summary Introduction and Background Namibia is among the most arid countries in southern Africa. Though it receives an average of 360mm of rainfall each year, 83 percent of this water evaporates immediately after rainfall. Another 14 percent goes towards vegetation, and 1 percent supplies the ground water in the region, thus leaving merely 2 percent for surface use. -

Sustainable Urban Transport Master Plan City of Windhoek

Sustainable Urban Transport Master Plan City of Windhoek Final - Main Report 1 Master Plan of City of Windhoek including Rehoboth, Okahandja and Hosea Kutako International Airport The responsibility of the project and its implementation lies with the Ministry of Works and Transport and the City of Windhoek Project Team: 1. Ministry of Works and Transport Cedric Limbo Consultancy services provided by Angeline Simana- Paulo Damien Mabengo Chris Fikunawa 2. City of Windhoek Ludwig Narib George Mujiwa Mayumbelo Clarence Rupingena Browny Mutrifa Horst Lisse Adam Eiseb 3. Polytechnic of Namibia 4. GIZ in consortium with Prof. Dr. Heinrich Semar Frederik Strompen Gregor Schmorl Immanuel Shipanga 5. Consulting Team Dipl.-Volksw. Angelika Zwicky Dr. Kenneth Odero Dr. Niklas Sieber James Scheepers Jaco de Vries Adri van de Wetering Dr. Carsten Schürmann, Prof. Dr. Werner Rothengatter Roloef Wittink Dipl.-Ing. Olaf Scholtz-Knobloch Dr. Carsten Simonis Editors: Fatima Heidersbach, Frederik Strompen Contact: Cedric Limbo Ministry of Works and Transport Head Office Building 6719 Bell St Snyman Circle Windhoek Clarence Rupingena City of Windhoek Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH P.O Box 8016 Windhoek,Namibia, www.sutp.org Cover photo: F Strompen, Young Designers Advertising Layout: Frederik Strompen Windhoek, 15/05/2013 2 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 15 1.1. Purpose ........................................................................................................................................ -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$6.00 WINDHOEK - 24 August 2018 No. 6689 Advertisements PROCEDURE FOR ADVERTISING IN 7. No liability is accepted for any delay in the publi- THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE cation of advertisements/notices, or for the publication of REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA such on any date other than that stipulated by the advertiser. Similarly no liability is accepted in respect of any editing, 1. The Government Gazette (Estates) containing adver- revision, omission, typographical errors or errors resulting tisements, is published on every Friday. If a Friday falls on from faint or indistinct copy. a Public Holiday, this Government Gazette is published on the preceding Thursday. 8. The advertiser will be held liable for all compensa- tion and costs arising from any action which may be insti- 2. Advertisements for publication in the Government tuted against the Government of Namibia as a result of the Gazette (Estates) must be addressed to the Government Ga- publication of a notice with or without any omission, errors, zette office, Private Bag 13302, Windhoek, or be delivered lack of clarity or in any form whatsoever. at Justitia Building, Independence Avenue, Second Floor, Room 219, Windhoek, not later than 12h00 on the ninth 9. The subscription for the Government Gazette is working day before the date of publication of this Govern- N$4,190-00 including VAT per annum, obtainable from ment Gazette in which the advertisement is to be inserted. Solitaire Press (Pty) Ltd., corner of Bonsmara and Brahman Streets, Northern Industrial Area, P.O. Box 1155, Wind- 3. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$9.60 WINDHOEK - 4 September 2020 No. 7328 Advertisements PROCEDURE FOR ADVERTISING IN 7. No liability is accepted for any delay in the publi- THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE cation of advertisements/notices, or for the publication of REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA. such on any date other than that stipulated by the advertiser. Similarly no liability is accepted in respect of any editing, 1. The Government Gazette (Estates) containing adver- revision, omission, typographical errors or errors resulting tisements, is published on every Friday. If a Friday falls on from faint or indistinct copy. a Public Holiday, this Government Gazette is published on the preceding Thursday. 8. The advertiser will be held liable for all compensa- tion and costs arising from any action which may be insti- 2. Advertisements for publication in the Government tuted against the Government of Namibia as a result of the Gazette (Estates) must be addressed to the Government Ga- publication of a notice with or without any omission, errors, zette office, Private Bag 13302, Windhoek, or be delivered lack of clarity or in any form whatsoever. at Justitia Building, Independence Avenue, Second Floor, Room 219, Windhoek, not later than 12h00 on the ninth 9. The subscription for the Government Gazette is working day before the date of publication of this Govern- N$4,190-00 including VAT per annum, obtainable from ment Gazette in which the advertisement is to be inserted. Solitaire Press (Pty) Ltd., corner of Bonsmara and Brahman Streets, Northern Industrial Area, P.O. Box 1155, Wind- 3. -

Water Consumption at Household Level in Windhoek, Namibia

Uhlendahl et al.: Water consumption Windhoek 2010 Albert Ludwigs University Institute for Culture Geography Final Project Report: Water consumption at household level in Windhoek, Namibia Survey about water consumption at household level in different areas of Windhoek depending on income level and water access in 2010 Authors: Dr. T. Uhlendahl and D. Ziegelmayer, Institute of Cultural Geography, Albert- Ludwigs University of Freiburg, Dr. A. Wienecke and M. L. Mawisa, Habitat Research and Development Center (HRDC) and Piet du Pisani, City of Windhoek (CoW) Project in cooperation with: Polytechnic of Namibia and Shack Dweller Federation of Namibia (SDFN) & Namibia Housing Action Group (NHAG) SDFN & NHAG Uhlendahl et al.: Water consumption Windhoek 2010 Table of contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 2. Targets............................................................................................................. 2 2.1. Water consumption depending on income level .............................................. 2 2.2. Specific purposes for which water is used ....................................................... 2 2.3. Evaluation of Windhoek’s water supply............................................................ 2 2.4. Approaches...................................................................................................... 3 3. State of knowledge ......................................................................................... -

Integrated Annual Report

INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT ’20 ORYX is a property loan stock company listed on the Namibian Stock Exchange (NSX) in the Financial Our 2020 performance at a glance IFC Real Estate sector. We are directly invested in property Oryx’s evolution 1 mainly in Namibia and have an How we compiled this report 2 investment in Croatia. This is our Integrated Annual Report What is important to know about Oryx 3 for the financial year ended What impacts our business 10 30 June 2020. Where we are going 16 Our leadership’s review of 2020 18 CONTENTS How we support our communities 33 How we practise good governance 36 How we reward performance 57 Appendices to the Integrated Annual Report 64 Annual Financial Statements 70 FEEDBACK Unitholder information and notice of AGM 150 Oryx is committed to improving its reporting, aligned Glossary 163 with best practice. Please provide any feedback and questions to [email protected]. Corporate information as at the date of this report 164 OUR 2020 PERFORMANCE AT A GLANCE Total distribution Property portfolio Market capitalisation 69.75 (cents per unit (cpu)) N$1.528 N$2.914 value (2019: N$1.704 billion) CPU (2019: 150.00) Bn Bn (2019: N$2.914 billion) Net asset value Net rental Gearing ratio N$1.912 (NAV) income growth 2.0% 39.1% (2019: 34.9%) Bn (2019: N$2.043 billion) (2019: 12%) Overall weighted Interest cover ratio Vacancy rate average cost of 2.3 (excluding interest (excluding 5.83% funding on linked debentures) 5.40% residentials) (2019: 9.2%1) times (2019: 2.96 times) (2019: 3.20%) 1 Excludes Euro loan. -

Housing Index in Due Course to Provide a Comparable Sectional Property Index

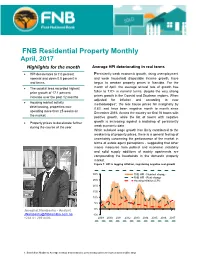

FNB Residential Property Monthly April, 2017 Highlights for the month Average HPI deteriorating in real terms HPI decelerates to 7.0 percent Persistently weak economic growth, rising unemployment nominal and down 0.8 percent in and weak household disposable income growth, have real terms. begun to weaken property prices in Namibia. For the The coastal area recorded highest month of April, the average annual rate of growth has price growth of 17.1 percent fallen to 7.0% in nominal terms, despite the very strong increase over the past 12 months prices growth in the Coastal and Southern regions. When adjusted for inflation and according to new Housing market activity methodologies¹, the real house prices fell marginally by deteriorating, properties now 0.8% and have been negative month to month since spending more than 25 weeks on December 2016. Across the country we find 16 towns with the market. positive growth, while the list of towns with negative Property prices to decelerate further growth is increasing against a backdrop of persistently during the course of the year. weak economic data. While subdued wage growth has likely contributed to the weakening of property prices, there is a general feeling of uncertainty concerning the performance of the market in terms of estate agent perceptions - suggesting that other macro measures from political and economic instability and solid supply additions of mainly apartments are compounding the headwinds in the domestic property market. Figure 1: HPI is lagging inflation, registering negative real growth 30% FNB HPI - Nominal change FNB HPI - Real change 25% Housing Inflation (CPI) 20% 15% 10% 5% Josephat Nambashu - Analyst 0% [email protected] -5% +264 61 299 8496 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 1. -

Location of Polling Stations, Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$34.00 WINDHOEK - 7 November 2014 No. 5609 CONTENTS Page PROCLAMATIONS No. 35 Declaration of 28 November 2014 as public holiday: Public Holidays Act, 1990 ............................... 1 No. 36 Notification of appointment of returning officers: General election for election of President and mem- bers of National Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 ................................................................................... 2 GOVERNMENT NOTICES No. 229 Notification of national voters’ register: General election for election of President and members of National Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 ............................................................................................... 7 No. 230 Notification of names of candidates duly nominated for election as president: General election for election of President and members of National Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 ................................... 10 No. 231 Location of polling stations: General election for election of President and members of National Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 .............................................................................................................. 11 No. 232 Notification of registered political parties and list of candidates for registered political parties: General election for election of members of National Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 ...................................... 42 ________________ Proclamations by the PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA No. 35 2014 DECLARATION OF 28 NOVEMBER 2014 AS PUBLIC HOLIDAY: PUBLIC HOLIDAYS ACT, 1990 Under the powers vested in me by section 1(3) of the Public Holidays Act, 1990 (Act No. 26 of 1990), I declare Friday, 28 November 2014 as a public holiday for the purposes of the general election for 2 Government Gazette 7 November 2014 5609 election of President and members of National Assembly under the Electoral Act, 2014 (Act No. 5 of 2014). Given under my Hand and the Seal of the Republic of Namibia at Windhoek this 6th day of November, Two Thousand and Fourteen. -

Of Water Reclamation for the Sustainable Future of Windhoek

Faculty Code: REL Project Sequence: 4703 IQP Division: 49B PERCEPTION AND COMMUNICATION OF WATER RECLAMATION FOR THE SUSTAINABLE FUTURE OF WINDHOEK AN INTERACTIVE QUALIFYING PROJECT REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE SPONSORING AGENCY: Department of Infrastructure, Water and Technical Services The City of Windhoek SUBMITTED TO: On-Site Liaison: Ferdi Brinkman, Chief Engineer Project Advisor: Reinhold Ludwig, WPI Professor Project Co-advisor: Svetlana Nikitina, WPI Professor SUBMITTED BY: ___________________________ Stefanie Crovello ___________________________ Joshua Davidson ___________________________ Amanda Keller DATE: 5th of May, 2010 PERCEPTION AND COMMUNICATION OF WATER RECLAMATION FOR THE SUSTAINABLE FUTURE OF WINDHOEK By: Stefanie Crovello Joshua Davidson Amanda Keller ABSTRACT The City of Windhoek, Namibia has a pioneering reclamation plant capable of recycling most of its wastewater into potable water. The goal of this project, sponsored by the City of Windhoek, was to assess the public perception and acceptability of the reclamation plant. Our findings reveal that the residents of Windhoek are vastly unaware of the reclamation process. It will be necessary for the City of Windhoek to promote public understanding through an effective outreach program. - i - ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The success of this project is due in part to the many people who volunteered their time and resources. We would like to acknowledge the following people for their contribution: Mr. Ferdi Brinkman Chief Engineer, City of Windhoek Department of Infrastructure, Water and Technical Services Mr. Brinkman served as our project sponsor and primary liaison throughout the entirety of the project. He has given our project the depth, direction and support necessary for its success. -

Network Operations

Network Operations Telecom Namibia strives to ensure a high level of network installed with 3177 customers provided with new voice + data integrity and reliability within the context of high efficiencies, services. including the development and management of appropriate supporting capacity in terms of performance monitoring and There are presently 43 active WiMAX sites in the country. These refinement, operational maintenance and fault repair services, are at Geluk, Siemenshof, Hermanstal, Klein Omatako, Maroe- projects planning and implementation capacities in the various laboom, Kombat, Reoland, Epukiro, Tamariskia, Maltahohe, technological areas as well as the capacities to provide security, NBC Windhoek Tower, Stampriet, Epako, The Glen, Channel 7, power and utilities at operational sites. Rossing Mountain, Okaputa, Omaere, Otavi, Affenberg, Wilhelm- sthal, Nyangana, Tsumore, Walvis Bay, Windhoek Central Hospi- During the year under review, Telecom Namibia continued to tal, Rocky Crest, Tsumis Park, Hardap, Windhoek NBC, Midgard deploy access technologies with a focus to extend the broad- Lodge, Okaparkaha, Ohangwena, Otjiberg, Brukaros, Gobabis, band capability of the last mile systems. The deployed systems Omboroko, Kapps Farm, NamPol Windhoek, Eersterus, Elisen- include wireless access (WiMAX), wireline access (ADSL) and heim, Gross Herzog, Adrianopel and Kalkrand. mobile access (CDMA - voice, 1x and EVDO). ADSL WiMAX The wireline access ADSL is extensively deployed countrywide A number of WiMAX base stations were deployed in rural areas as an access broadband system to connect customers. The (and a limited number in urban areas) to provide voice and total port capacity deployed to date is 19 437 with 9 640 broadband services to rural customers and recover outdated customers connected. -

The Windhoek Structure Plan

THE WINDHOEK STRUCTURE PLAN WINDHOEK MUNICIPALITY OCTOBER 1996 THE WINDHOEK STRUCTURE PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Town Planning Goals 2. Council's Vision 3. Objectives 4. Background to the City 5. The City Centre 6. Water Supply 7. Population Growth 8. Urbanisation 9. Municipal Area & Area of Expansion 10. Influence of Land Transport Routes 11. Linear Pattern 12. Common Trend 13. Benefits of the Linear Model 14. The Choice 15. Business Enterprise Locations 16. Retail Hierarchy 17. Guidelines for Suburban Business Development 18. Public Transport 19. Infrastructure 20. Housing 21. Sustainable Development 22. Recreation and the Environment 23. Rural Periphery 24. Finance 25. Regional Extension 26. Summary of Significant Statements 27. Structure for Strategies 28. Council Resolution 29. References PLANS Plan 1: Windhoek-Okahandja Urban Corridor Plan 2: Windhoek Guide Plan P/1700/S Rev.4 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Simple Sustainability Criteria ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS 1. Development Potential of the Northern Peri-urban Areas of Windhoek (Brakwater) 2. 1993 Update of the Greater Windhoek Transportation Study 1. TOWN PLANNING GOALS Town Planning has as a general goal the aim of promoting the continued co-ordinated and harmonious development of Windhoek in such a way as will most effectively tend to promote health, safety, order, amenity, convenience and general welfare, as well as efficiency and cost effectiveness in the process of development, the attraction of new investment and the improvement of communications. To contribute its part towards the mission of Council, this report seeks to anticipate and draw Council's attention to trends and changes in urban development which may need to be addressed and to advise Council on plans and guidelines which may be recommended to handle the physical planning of land use and urbanisation.