THE UNION BUILDING (FORMER DECKER BUILDING) , 3 3 Union Square West, Borough of Manhattan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

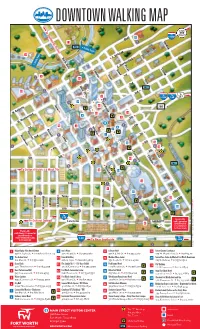

Downtown Walking Map

DOWNTOWN WALKING MAP To To121/ DFW Stockyards District To Airport 26 I-35W Bluff 17 Harding MC ★ Trinity Trails 31 Elm North Main ➤ E. Belknap ➤ Trinity Trails ★ Pecan E. Weatherford Crump Calhoun Grov Jones e 1 1st ➤ 25 Terry 2nd Main St. MC 24 ➤ 3rd To To To 11 I-35W I-30 287 ➤ ➤ 21 Commerce ➤ 4th Taylor 22 B 280 ➤ ➤ W. Belknap 23 18 9 ➤ 4 5th W. Weatherford 13 ➤ 3 Houston 8 6th 1st Burnett 7 Florence ➤ Henderson Lamar ➤ 2 7th 2nd B 20 ➤ 8th 15 3rd 16 ➤ 4th B ➤ Commerce ➤ B 9th Jones B ➤ Calhoun 5th B 5th 14 B B ➤ MC Throckmorton➤ To Cultural District & West 7th 7th 10 B 19 12 10th B 6 Throckmorton 28 14th Henderson Florence St. ➤ Cherr Jennings Macon Texas Burnett Lamar Taylor Monroe 32 15th Commerce y Houston St. ➤ 5 29 13th JANUARY 2016 ★ To I-30 From I-30, sitors Bureau To Cultural District Lancaster Vi B Lancaster exit Lancaster 30 27 (westbound) to Commerce ention & to Downtown nv Co From I-30, h exit Cherry / Lancaster rt Wo (eastbound) or rt Summit (westbound) I-30 To Fo to Downtown To Near Southside I-35W © Copyright 1 Major Ripley Allen Arnold Statue 9 Etta’s Place 17 LaGrave Field 25 Tarrant County Courthouse 398 N. Taylor St. TrinityRiverVision.org 200 W. 3rd St. 817.255.5760 301 N.E. 6th St. 817.332.2287 100 W. Weatherford St. 817.884.1111 2 The Ashton Hotel 10 Federal Building 18 Maddox-Muse Center 26 TownePlace Suites by Marriott Fort Worth Downtown 610 Main St. -

11 Houston Street Greenock PA16 8DA

11 HOUSTON STREET Greenock PA16 8DA Residential Development Opportunity 11 Houston Street Greenock 2 OPPorTUNITY We are delighted to present a site to the market at 11 Houston Street, Greenock which lies close to the Greenock waterfront. The available site extends to approximately 0.35 acres (0.14 hectares) and previously had planning consent for the development of 22 apartments with 26 surfaced car parking spaces. A suite of technical information is available for review upon registration of interest. LOCATION The site is set on the western edge of Greenock Town Centre on Houston Street. Greenock is the largest town within the Local Authority area of Inverclyde. It lies approximately 27 miles west of the City of Glasgow on the southern side of the Firth of Clyde. Greenock has historically been one of the most important Scottish ports and whilst not at the same level of activity as it once was, is still a thriving port and provides docking for Ocean Liners. Greenock provides a wide range of retail and leisure offers within close proximity of the subjects and has excellent road and public transport connections to Glasgow and the surrounding areas. The M8 motorway provides direct access to Glasgow and Edinburgh and Greenock has an extensive rail network with the nearest station to the site being Greenock West station which lies approximately 0.6 miles south east of the subjects. This provides rail connections to Glasgow and Paisley. Ferry Services in nearby Gourock provide passengers and cars with access to Dunoon and Kilcreggan. In close proximity to the subjects there are a number of local amenities such as Ardgowan Bowling Club, Greenock Cricket Club and Greenock Golf Club. -

Report: Federal Houses Landmarked Or Listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places 1999

GREENWICH VILLAGE SOCIETY FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION Making the Case Federal Houses Landmarked or Listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places 1999-2016 The many surviving Federal houses in Lower Manhattan are a special part of the heritage of New York City. The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation has made the documentation and preservation of these houses an important part of our mission. This report highlights the Society’s mission in action by showing nearly one hundred fifty of these houses in a single document. The Society either proposed the houses in this report for individual landmark designation or for inclusion in historic districts, or both, or has advocated for their designation. Special thanks to Jiageng Zhu for his efforts in creating this report. 32 Dominick Street, built c.1826, landmarked in 2012 Federal houses were built between ca. 1790 to ca. 1835. The style was so named because it was the first American architectural style to emerge after the Revolutionary War. In elevation and plan, Federal Period row houses were quite modest. Characterized by classical proportions and almost planar smoothness, they were ornamented with simple detailing of lintels, dormers, and doorways. These houses were typically of load bearing masonry construction, 2-3 stories high, three bays wide, and had steeply pitched roofs. The brick facades were laid in a Flemish bond which alternated a stretcher and a header in every row. All structures in this report were originally built as Federal style houses, though -

Lower Manhattan

WASHINGTON STREET IS 131/ CANAL STREETCanal Street M1 bus Chinatown M103 bus M YMCA M NQRW (weekday extension) HESTER STREET M20 bus Canal St Canal to W 147 St via to E 125 St via 103 20 Post Office 3 & Lexington Avs VESTRY STREET to W 63 St/Bway via Street 5 & Madison Avs 7 & 8 Avs VARICK STREET B= YORK ST AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 6 only6 Canal Street Firehouse ACE LISPENARD STREET Canal Street D= LAIGHT STREET HOLLAND AT&T Building Chinatown JMZ CANAL STREET TUNNEL Most Precious EXIT Health Clinic Blood Church COLLISTER STREET CANAL STREET WEST STREET Beach NY Chinese B BEACH STStreet Baptist Church 51 Park WALKER STREET St Barbara Eldridge St Manhattan Express Bus Service Chinese Greek Orthodox Synagogue HUDSON STREET ®0= Merchants’ Fifth Police Church Precinct FORSYTH STREET 94 Association MOTT STREET First N œ0= to Lower Manhattan ERICSSON PolicePL Chinese BOWERY Confucius M Precinct ∑0= 140 Community Plaza Center 22 WHITE ST M HUBERT STREET M9 bus to M PIKE STREET X Grand Central Terminal to Chinatown84 Eastern States CHURCH STREET Buddhist Temple Union Square 9 15 BEACH STREET Franklin Civic of America 25 Furnace Center NY Chinatown M15 bus NORTH MOORE STREET WEST BROADWAY World Financial Center Synagogue BAXTER STREET Transfiguration Franklin Archive BROADWAY NY City Senior Center Kindergarten to E 126 St FINN Civil & BAYARD STREET Asian Arts School FRANKLIN PL Municipal via 1 & 2 Avs SQUARE STREET CENTRE Center X Street Courthouse Upper East Side to FRANKLIN STREET CORTLANDT ALLEY 1 Buddhist Temple PS 124 90 Criminal Kuan Yin World -

1025 15Th Street NW

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE * * * HISTORIC PRESERVATION REVIEW BOARD APPLICATION FOR HISTORIC LANDMARK OR HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION New Designation X Amendment of a previous designation Please summarize any amendment(s) ______________________ Propertyname~T=h=e~E=th=e=l=h=m=s=t ________________________________________________ Ifan y part ofthe interior is being nominated, it must be specifically identified and described in the narrative statements. Address 1025 151h Street N.W. Square and lot number(s) -'="S~qu=a=r=e=2-"-16"'--"==L=o!:....t0=0=2=6'--------------------- Affected Advisory Neighborhood Commission .!.-'AN:=....:....:C::::....=2~F______________________________ _ Date of construction 1902 Date ofmajor alteration(s)______________ _ Architect(s) T. Franklin Schneider Architectmal style(s) .::::B~ea=u~x!....:Art~~s _________ Original use Residence/Multi-Family Present use Commercial/Office Property owner Honeybee Hospitality LLC Legal address of property owner 1842 16th Street NW, Washington, DC 20009 NAME OF APPLICANT(S) Megan Merrifield, Honeybee Hospitality LLC (owner) If the applicant is an organization, it must submit evidence that among its purposes is the promotion of historic preservation in the District of Columbia. A copy of its charter, articles of incorporation, or by-laws, setting forth such purpose, will satisfy this requirement. Address/Telephone ofapplicant(s) 1842 16th Street NW, Washington, DC 20009 (757) 553-7906 Name and title of authorized representative Stu.- M AILvalA f'(2.E.SEfl..l{A]ol\/ PLAtv'NE~ 1 ~ _. .. OA. e.ttT"ftz.A<,G~es Signature of representative -vv'?[J & Date AP!1.Jt.. 10, Z.OI'-J Name and telephone of author of application Gray O'Dwyer, EHT Traceries (202) 393-1199 D>te ,~,;,oo ~ l?'J'/ { H.P.O.statf -~ ~~~ '\.1\ Office of Planning, II 00 4'h Street, SW, Suite E650, Washington, D.C. -

151 Canal Street, New York, NY

CHINATOWN NEW YORK NY 151 CANAL STREET AKA 75 BOWERY CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION GROUND FLOOR Northeast corner of Bowery CANAL STREET SPACE 30 FT Ground Floor 2,600 SF Basement 2,600 SF 2,600 SF Sub-Basement 2,600 SF Total 7,800 SF Billboard Sign 400 SF FRONTAGE 30 FT on Canal Street POSSESSION BASEMENT Immediate SITE STATUS Formerly New York Music and Gifts NEIGHBORS 2,600 SF HSBC, First Republic Bank, TD Bank, Chase, AT&T, Citibank, East West Bank, Bank of America, Industrial and Commerce Bank of China, Chinatown Federal Bank, Abacus Federal Savings Bank, Dunkin’ Donuts, Subway and Capital One Bank COMMENTS Best available corner on Bowery in Chinatown Highest concentration of banks within 1/2 mile in North America, SUB-BASEMENT with billions of dollars in bank deposits New long-term stable ownership Space is in vanilla-box condition with an all-glass storefront 2,600 SF Highly visible billboard available above the building offered to the retail tenant at no additional charge Tremendous branding opportunity at the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge with over 75,000 vehicles per day All uses accepted Potential to combine Ground Floor with the Second Floor Ability to make the Basement a legal selling Lower Level 151151 C anCANALal Street STREET151 Canal Street NEW YORKNew Y |o rNYk, NY New York, NY August 2017 August 2017 AREA FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS/BRANCH DEPOSITS SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LUDLOW STREET ESSEX STREET SUFFOLK STREET CLINTON STREET ATTORNEY STREET NORFOLK STREET LEGEND LUDLOW -

View Printable Directions

MANHATTAN CAMPUS OF THE VA NY HARBOR HEALTHCARE SYSTEM 423 East 23rd Street New York, NY 10010-5011 PUBLIC TRANSIT By Subway: The IRT "N" and "R" trains stop at 23rd Street and Broadway. The "1" and "9" trains stop at 23rd Street and 7th Avenue. The "6" train stops at 23rd Street and Park Avenue South. Take the "L" train to 14th Street. Exit at the 18th Street exit and walk five blocks to the hospital. By Bus: The M16 stops directly across from the hospital on 23rd Street. This bus can be boarded by Penn Station near the corner of 34th Street & 8th Avenue and 34th Street & 7th Avenue. The M15 picks up and drops off at the intersection of 23rd Street and 1st Avenue. The M23 stops at 1st Avenue and 23rd Street. The Command Bus from Brooklyn stops at 23rd Street and 1st Avenue. DRIVING DIRECTIONS By Car From Newark Airport: Take US 1/9 North to the Pulaski Skyway to the Holland Tunnel. Proceed to the Alternate Canal Street exit (3rd right) and make a left at the 2nd light at 6th Avenue. Turn right on Houston Street, then left on 1st Avenue and right on 23rd Street. By Car From the George Washington Bridge: Take the Cross Bronx Expressway to the Major Deegan Expressway (Rt 87) South to the FDR Drive South. Exit at 23rd Street. During construction, however, you are forced to drive onto 25th Street, so make an immediate left on Asser Levy Place to 23rd Street. The hospital is on the right. -

QUES in ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1

[email protected] - QUES IN ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1 Faculty: Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Reinhold Martin, Mabel O. Wilson Teaching Fellows: Oskar Arnorsson, Benedict Clouette, Eva Schreiner Thurs 11am-1pm Fall 2016 This two-semester introductory course is organized around selected questions and problems that have, over the course of the past two centuries, helped to define architecture’s modernity. The course treats the history of architectural modernity as a contested, geographically and culturally uncertain category, for which periodization is both necessary and contingent. The fall semester begins with the apotheosis of the European Enlightenment and the early phases of the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. From there, it proceeds in a rough chronology through the “long” nineteenth century. Developments in Europe and North America are situated in relation to worldwide processes including trade, imperialism, nationalism, and industrialization. Sequentially, the course considers specific questions and problems that form around differences that are also connections, antitheses that are also interdependencies, and conflicts that are also alliances. The resulting tensions animated architectural discourse and practice throughout the period, and continue to shape our present. Each week, objects, ideas, and events will move in and out of the European and North American frame, with a strong emphasis on relational thinking and contextualization. This includes a historical, relational understanding of architecture itself. Although the Western tradition had recognized diverse building practices as “architecture” for some time, an understanding of architecture as an academic discipline and as a profession, which still prevails today, was only institutionalized in the European nineteenth century. -

New York's Mulberry Street and the Redefinition of the Italian

FRUNZA, BOGDANA SIMINA., M.S. Streetscape and Ethnicity: New York’s Mulberry Street and the Redefinition of the Italian American Ethnic Identity. (2008) Directed by Prof. Jo R. Leimenstoll. 161 pp. The current research looked at ways in which the built environment of an ethnic enclave contributes to the definition and redefinition of the ethnic identity of its inhabitants. Assuming a dynamic component of the built environment, the study advanced the idea of the streetscape as an active agent of change in the definition and redefinition of ethnic identity. Throughout a century of existence, Little Italy – New York’s most prominent Italian enclave – changed its demographics, appearance and significance; these changes resonated with changes in the ethnic identity of its inhabitants. From its beginnings at the end of the nineteenth century until the present, Little Italy’s Mulberry Street has maintained its privileged status as the core of the enclave, but changed its symbolic role radically. Over three generations of Italian immigrants, Mulberry Street changed its role from a space of trade to a space of leisure, from a place of providing to a place of consuming, and from a social arena to a tourist tract. The photographic analysis employed in this study revealed that changes in the streetscape of Mulberry Street connected with changes in the ethnic identity of its inhabitants, from regional Southern Italian to Italian American. Moreover, the photographic evidence demonstrates the active role of the street in the permanent redefinition of -

Muse2016v50p75-89.Pdf (4.825Mb)

Fallen Angel A Case Study in Architectural Ornamentation w. arthur mehrhoff According to the late anthropologist James Deetz, we can decode cultural meanings from the past most fully by studying “small things often overlooked and even forgotten.”1 While architectural historians often train their scholarly lenses on landmark buildings and structures, vernacular objects such as doorways, gravestones, and even discarded architectural orna- ments offer students of culture a kind of intellectual “mortar” that can help them fit larger structures to- gether into a conceptual whole.2 The Museum of Art and Archaeology’s winged terracotta figure, a splendid example of architectural ornament and a survivor of urban redevelopment, was one of a series of similar figures that originally graced the elaborate frieze of the 1898 twelve-story Title Guaranty Building, one of the earliest tall office buildings in downtown St. Louis. The building, known at its construction as the Lincoln Trust Building, was destroyed in 1983. The Fallen Angel The figure stands facing to the front with arms crossed at her waist (Fig. 1 and back cover).3 Constructed in three parts–base and lower part of a plinth, upper half of plinth, and upper body–she Fig. 1. Architectural winged figure in high relief, 1898, terra- cotta. H. 2.140 m. From the Title Guaranty Building (originally the Lincoln Trust Building), St. Louis, Missouri. Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri (84.109a–c), gift of Mr. and Mrs. Mark A. Turken and Mr. and Mrs. Paul L. Miller, Jr. Photo: Jeffrey Wilcox. 75 FALLEN ANGEL Fig. 2. -

STEINWAY HALL, 109-113 West 57T1i Street (Aka 106-116 West 58L" Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 13, 2001, Designation List 331 LP-2100 STEINWAY HALL, 109-113 West 57t1i Street (aka 106-116 West 58l" Street), Manhattan. Built 1924-25; [Whitney] Warren & [Charles D.] Wetmore, architects; Thompson-Starrett Co., builders. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1010, Lot 25. October 16, 2001 , the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of Steinway Hall and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 3). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions oflaw. Eight people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the property's owners, Community Board 5, Municipal Art Society, American Institute of Architects' Historic Buildings Committee, and Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission received two letters in support of designation, including one from the New York Landmarks Conservancy. Summary The sixteen-story Steinway Hall was constructed in 1924-25 to the design of architects Warren & Wetmore for Steinway & Sons, a piano manufacturing firm that has been a dominant force in its industry since the 1860s. Founded in 1853 in New York by Heinrich E. Steinweg, Sr., the firm grew to worldwide renown and prestige through technical innovations, efficient production, business acumen, and shrewd promotion using artists' endorsements. From 1864 to 1925, Steinway's offices/showroom, and famous Steinway Hall (1866), were located near Union Square. After Carnegie Hall opened in 1891, West 57t1i Street gradually became one of the nation's leading cultural and classical music centers and the piano companies relocated uptown. It was not until 1923, however, that Steinway acquired a 57th Street site. -

CHARNLEY, JAMES, HOUSE Ot

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CHARNLEY, JAMES, HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: CHARNLEY, JAMES, HOUSE Other Name/Site Number: CHARNLEY-PERSKY HOUSE 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1365 North Astor Street Not for publication: City/Town: Chicago Vicinity: State: IL County: Cook Code:031 Zip Code:60610-2144 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X_ Building(s): X Public-Local: __ District: __ Public-State: __ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 __ buildings __ sites __ structures __ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CHARNLEY, JAMES, HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria.