"Shock" Meets "Community Service": J.C. Corcoran at KMOX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KMOX I70 Series OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF

Updated 6/21 KMOX I70 Series OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE ENTRANT’S CHANCE OF WINNING. 1. HOW TO ENTER a. These rules govern the KMOX I70 Series promotion (the “Promotion”), which is being conducted by KMOX(AM) (the “Station”). The Promotion begins on Tuesday, June 20, 2017 and ends on Wednesday, July 26, 2017 (the “Promotion Dates”). b. To enter the Promotion, entrant may enter on-site at a participating Llywelyn’s Pub location on dates and times as specified below (each an “Event”) to obtain an official entry form (available while supplies last), legibly hand write your first name and last name, complete address, city, state, zip code, telephone number (including area code), and date of birth on an official entry form and place the completed entry form in the dedicated collection box. P.O. Boxes are not permitted. All entries must be received by the end time for each Event as listed below. Entries submitted may not be acknowledged or returned. Failure to provide all required information may result in disqualification. i. Tuesday, June 20, 2017 at St. Peter’s Llywelyn’s Pub Location , (3300 Mid Rivers Mall Dr, St Peters, MO 63376) beginning at 5:00 PM Central Time (“CT”) and ending at 8:00 PM CT. ii. Tuesday, July 11, 2017 at the Webster Groves Llywelyn’s Location (17 W Moody, Webster Groves, MO 63119) beginning at 5:00 CT and ending at 8:00 PM CT. iii. -

KEZK-FM, KFTK, KFTK-FM, KMOX, KNOU, KYKY EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT October 1, 2019 - September 30, 2020

Page: 1/13 KEZK-FM, KFTK, KFTK-FM, KMOX, KNOU, KYKY EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT October 1, 2019 - September 30, 2020 ENTERCOM St. Louis,MO IS AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY EMPLOYER. Address: Contact Person/Title: 1220 Olive Street, Becky Domyan 3rd Floor, SVP/Market Manager St Louis, MO - 63103 Telephone Number: E-Mail Address: 314-621-2345 [email protected] I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree 1-4, 6-8, 10-14, 16-20, 22-31, 33-43, 45 Account Executive 51 -48, 50-51, 53-54, 56-58 1-4, 6-8, 10-14, 16-20, 22-31, 33-43, 45 Account Executive 58 -48, 50-51, 53-54, 56-58 1-4, 6-8, 10-14, 16-20, 22-31, 33-43, 45 Account Executive 53 -48, 50-51, 53-54, 56-58 1-4, 6-10, 12-14, 16-20, 22-48, 50, 52- Sales Assistant - St. Louis 53 54 1-4, 6-8, 10-14, 16-20, 22-28, 30-31, 33 Mid Day Air Talent - St. Louis 55 -35, 37-43, 45-47, 50-51, 55 Account Manager 1-4, 6-8, 10-14, 16-48, 50-51, 55, 58 51 Account Executive - St. Louis 1-8, 10-51, 58-59 51 Page: 2/13 KEZK-FM, KFTK, KFTK-FM, KMOX, KNOU, KYKY EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT October 1, 2019 - September 30, 2020 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") a. Agencies Notified by Outreach Source Entitled No. -

AM RADIO STATIONS (50Kw) Sorted by City

AM RADIO STATIONS (50kW) Sorted by City: Frequency Station kHz City State WDCD 1540 Albany NY KKOB 770 Albuquerque NM KENI 650 Anchorage AK KFQD 750 Anchorage AK WSB 750 Atlanta GA WBAL 1090 Baltimore MD KBOI 670 Boise ID WRKO 680 Boston MA WEEI 850 Boston MA WBZ 1030 Boston MA WWZN 1510 Boston MA WWKB 1520 Buffalo NY KTWO 1030 Casper WY WBT 1110 Charlotte NC WSCR 670 Chicago IL WGN 720 Chicago IL WBBM 780 Chicago IL WLS 890 Chicago IL WMVP 1000 Chicago IL WLW 700 Cincinnati OH WSAI 1530 Cincinnati OH WTAM 1100 Cleveland OH WHK 1220 Cleveland OH KRLD 1080 Dallas TX KFXR 1190 Dallas TX KOA 850 Denver CO WHO 1040 Des Moines IA WJR 760 Detroit MI WWJ 950 Detroit MI WXYT 1270 Detroit MI KPNW 1120 Eugene OR WFDF 910 Farmington Hills MI WOWO 1190 Fort Wayne IN KMJ 580 Fresno CA KYNO 940 Fresno CA WBAP 820 Ft Worth TX WLFJ 660 Greenville SC WALE 990 Greenville RI WTIC 1080 Hartford CT KTRH 740 Houston TX KMNY 1360 Hurst TX KOFI 1180 Kalispell MT KDWN 720 Las Vegas NV KRVN 880 Lexington NE KAAY 1090 Little Rock AR KFI 640 Los Angeles CA KSPN 710 Los Angeles CA KTNQ 1020 Los Angeles CA KNX 1070 Los Angeles CA KTLK 1150 Los Angeles CA KMPC 1540 Los Angeles CA WHAS 840 Louisville KY WMAC 940 Macon GA WAQI 710 Miami FL WTMJ 620 Milwaukee WI WISN 1130 Milwaukee WI KVTT 1110 Mineral Wells TX WCCO 830 Minneapolis MN KTCN 1130 Minneapolis MN WSM 650 Nashville TN WLAC 1510 Nashville TN WWL 870 New Orleans LA WFAN 660 New York NY WOR 710 New York NY WABC 770 New York NY WCBS 880 New York NY WINS 1010 New York NY WEPN 1050 New York NY WBBR 1130 New York -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

CLIENT: MK Ferguson STATION: KMOX Radio PROGRAM: KMOX

• I S.* • • b..* • ••••• I 1•••Smo, • ••••• • • • N..* • • Sm.• • • \I — V, ✓ ∎ I • • • %.** • NEW YORK PHILADELPHIA ST. LOUIS DENVER 7838 Big Bend Boulevard, St. Louis, Missouri 63119 (314) 961-4113 CLIENT: MK Ferguson STATION: KMOX Radio PROGRAM: KMOX 'Radio News TIME: 6:06 A.M. DATE: 12/17/92 CITY: St. Louis BOB HARDY: "Weldon Spring residents voiced concern last night about the government's $650 million dollar proposal to bury millions of tons of radioactive and chemical waste on a 42 acre site. KMOX Radio's Kevin McCarthy reports that story." KEVIN MCCARTHY: "Last night citizens of St. Charles County gathered to discuss a multimillion dollar Department of Energy proposal to permanently store more than 900,000 cubir yards of radioactive waste at a site near Weldon Spring. That nda was quickly derailed when members of Labor Local 6 .60 questioned the hiring practices of government contractors. "Steve McCracken of the Department of Energy responds." STEVE MCCRACKEN: "This is a federal government project and that means that we have to follow fair and open competition • and that competition determines who gets the work." MCCARTHY: "Other concerns of workers included on-site job safety training as well as possible safety violations re- garding asbestos removal at the Weldon Spring site. "In St. Charles, I'm Kevin McCarthy for AM 1120, KMOX Radio News." Aaterial supplied by BIS, Inc. may be used for file and reference purposes only. It may not be reproduced, sold or publicly demonstrated or exhibited. rhe above transcript has been edited for readability eliminating verbal hesitations. Unintelligible phrases are enclosed in parentheses. -

Shift from WGN Recalls Old Comfort Zone for Fans, Station, Cubs

Shift from WGN recalls old comfort zone for fans, station, Cubs By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Monday, June 9th, 2014 Wowww! Let’s go, batter up, we’re taking the afternoon off….It’s a beautiful day for a ballgame, for a ballgame today. The fans are out to get a ticket or two, from Walla Walla, Washington to Kalamazoo… Everything changes – even the most comfy things that fit to a tee. Familiarity and memories of childhood soundtracks of summer is why we’re all wrung out with the news the Cubs’ radio rights have shift- ed to WBBM-Radio from their 57-season home 60 kc down the dial at WGN. The news wasn’t unexpected. WGN re- opened its Cubs contract – not the other way around – before this season because it was losing its financial shirt, unable to re- coup enough ad revenue to cover produc- tion costs when the baseball ratings had gone in the dumper. A move like this be- came inevitable – just the timing was in question – after Tribune Co. sold the Cubs to the cash-hungry Ricketts family, which is saddled with a heavy debt service man- dated by corporate shark Sam Zell as the structure of the sale. Lou Boudreau (top) and Jack Quinlan in WGN- As long as Tribune Co. -- which acquired Radio's first season with the Cubs radio rights in the embryonic WGN in 1924 -- had um- 1958. brella ownership of the Cubs and WGN TV -radio properties, change was going to be far off in the future. But all bets were off once the team and broadcasters diverged under www.ChicagoBaseballMuseum.org [email protected] separate corporate entities. -

The Death Penalty in 2013: Year End Report

! ! THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2013: YEAR END REPORT Media Coverage Summary ! DPIC’s 2013 Year End Report was released on December 19, 2013, receiving extraordinary coverage. Coverage of the report appeared in over 500 media outlets, and was notable in two important respects. First, there was an increase in the amount of news coverage and editorial board attention. Second, 2013 was the year the media reported and underscored our message that “[a] societal shift is underway,” as quoted in the New York Times. Coverage of the 2013 Year End Report included stories in the New York Times, Washington Post, USA Today, Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal, Time, CNN, Associated Press, Reuters and AFP, and in hundreds of other articles and editorials. Richard Dieter was interviewed on MSNBC-TV and C-SPAN’s Washington Journal. Stories also ran on NPR (two stories), CBS, ABC, NBC, and Associated Press Radio Networks. As an example of our use of new media, The Guardian (which now has web traffic inside the U.S. similar to the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times) hosted an online chat about the report with DPIC’s Executive Director. The theme of a fundamental change in the country was echoed widely. For example, newspapers in North Carolina carried DPIC’s observation that the decline of the death penalty was not a "one-year quirk … It's indicative of some broad changes in society.” This theme was reflected in New York Times and Washington Post editorials, as well as editorials in Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Nebraska, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. -

Entercom Missouri, LLC

UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT OFFICE Notice of Contact Information For Transmitting Entities Publicly Performing Pre-1972 Sound Recordings In accordance with section 1401 of title 17 of the U.S. Code and section 201.36 of title 37 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the transmitting entity named below hereby files notice of its contact information and its public performance of sound recordings fixed before February 15, 1972, by means of digital audio transmission ("Notice of Contact Information"). The fee to file this Notice of Contact Information is $105.00, with an additional $35.00 fee for each alternate name provided below. Check, if applicable, and provide date of original filing: Amended filing; Date of original filing: Please type the requested information for each item. If you need more space to provide the requested information, please provide it in response to question 7. 1 Name of transmitting entity: Entercom Missouri, LLC 2 Address: Line 1: 401 E. City Ave., Suite 809 Line 2: City: Bala Cynwyd State: Pennsylvania Zip: 19004 Country: United States 3 a. Telephone Number: 610-660-5610 b. Email Address: [email protected] 4 Website(s) and/or application(s) through which the transmitting entity publicly performs pre-1972 sound recordings by means of digital audio transmission: Radio.com, Radio.com App, kezk.radio.com, y98.radio.com, now963.radio.com, kmox.radio.com, 971talk.radio.com 5 Include alternate name(s) of transmitting entity (i.e., names the public would be likely to use to search for the transmitting entity in the Copyright Office's directory of transmitting entities). -

Bo Matthews Resume

BO MATTHEWS REPRESENTED BY WEST MODEL & TALENT MANAGEMENT 636-527-7473 PROFILE Early on I learned there was power in the microphone. Since 1985 my goal has been to use that power to entertain, motivate, promote and communicate with the listener. My career has evolved into music and talk radio, social media connection and voiceovers. EXPERIENCE VOICEOVER ARTIST, BO MATTHEWS MEDIA — 2018–PRESENT After 33 years in radio and TV broadcasting , my natural transition to voiceover artist was evident. Working from my private pro-grade studio on my property and with local recording studios I’ve had the pleasure of voicing narration projects, promotions, radio imaging, commercials and On Hold messages. ST. LOUIS WORKS PODCAST HOST, ENTERCOM - 2019 This podcast is a recruitment podcast to connect companies to good candidates for employment. “When everyone works, St. Louis Works” TALK SHOW HOST, 1120 KMOX & 97.1 KFTK 2019-PRESENT When needed I’ve been asked to cover shows on two St. Louis Talk stations. Subjects include the news of the day, Politics, lifestyle and sports stories that are making headlines and interviewing guests and callers. AFTERNOON DRIVE HOST, 92.3 WIL, ST. LOUIS, MO — 2005-2018 A second stint as Afternoon Drive host and social media expert, entertaining with daily headlines and life stories were part of my music intense show. I produced great ratings and monster revenue. Specializing in endorsement advertising. On site interacting with listeners at concerts, clients and charitable events was also a passion of mine. MORNING SHOW HOST, K92FM, ORLANDO, FL — 2002-2005 Hosting the K92 morning show The Bo and Melissa show, featuring great music and phone and in studio interviews with music stars, celebrities and local constituents. -

Loyola University Chicago

Loyola Ramblin’ (wo)man on the street { hat is yor faorite holiday tradition } INSIDE Jeremy Boni / General Manager, Ellen Landgraf, CPA, PhD / Associate Professor, Accounting Chris M. Murphy / Associate Vice President for Mission Loyola University Chicago Bookstores “Every year of my life I have been fortunate to have a real Christmas and Ministry, Director of University Ministry “My family and I stay up all night on Thanksgiving, tree at home. This tradition appeared to be threatened some years “Our family opens gifts on Christmas Day, but saves the playing cards and board games. Then we go out shopping back when I purchased a Mini Cooper (which would not accommodate stocking stuffers for last. The stockings are fi lled with small at 4 a.m. to catch all the “Black Friday” shopping deals. We my need for a seven foot balsam!). Thank goodness for the World gifts, unwrapped, that family members fi nd throughout the always like to watch how focused, and sometimes intense, Wide Web. I am now able to procure my real tree, fresh-cut from year. Each gift somehow refl ects the persona of the person NEWS FOR FACULTY AND STAFF LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO | DEC 2007 people get about shopping. Back in Ohio, “Black Friday” is New Hampshire. It comes in a 10 foot by 15 inch rectangular box via receiving the gift. It is a fun challenge to keep one’s eyes open Loyola a serious event!” FedEx. We call it the tree-in-a-box.” throughout the whole year for just the right small memento.” VP, University Marketing Director of Communications Contributors Photography Graphic Designer & Communications Maeve Kiley Annie Busiek, Steve Christensen, Mark Beane Alisha Roeder Kelly Shannon Annie Hughes, Brendan Keating, Kathleen Neuman, Lenzlee Ruiz Inside Loyola is published by Loyola University Chicago, Division of University Marketing and Communications, 820 N. -

What's A* Jthe

What's A* Jthe The Journal Schedule* 14 MADISON, FRIDAY, MARCH 20, 1942 B:30 Familiar Music—WTMJ WMAQ 11:00 Church of Deliverance—WIND Frequencies Other Stations Saturday News Broadcasts 8:30 Irene Rich—WENR WLW 11:00 Harry James Orch.—WBBM WHA Sunday 1310 VVCIN 120 WIBA to Air Presentation Morning BIJNDAT 8:45 Dinnh Shore— WENH WLW 11:05 Jan Garbcr Orch.—WGN 1:00 Organ Melodies. IT IIA 970 WIND SBO A. M. '1 nil WTND !):00 Revival Hour—WIND WCFL 11:05 Gene Krupa Orch.—WENR 1:10 Background* of Today's Kv»nUl II :oo Musical C.'lot-k WHBM »:00 Houi of Charm—WMAQ WTMJ KSTP 1500 WLUL •3D e :oo Pralrlu nninlilri-s—WI,S 7:00 WI..W KMOX 4-ia WJJD 11:05 Francis CrnlK WMAO WTMJ Prof. Waller Morion. WBBM HO WLS S90 B :uu Sunrise Special- -WTMJ 1 :OC> WIltiM VV IHA 4 :45 WCCO WBBM B:00 Good Will [!our—WKNH 11:15 Dick Jurgens Orch -WON 1:45 Books 1 Like: Prof. W«lt«r WCtO 830 WLW S9D of Trophy to Johnny Kotz 6:00 Breakfast Time Fro lies—WGN 8:00 WIBA WLW 5:00 WIND B:00 Take II or Leave It- WBBM 11:30 Moon River—WMAQ WTMJ Agard. WCFL 1000 WMAQ 670 8:00 WMAQ WBB1V 5:15 WJJD 9:30 'Cod-Given Rights'—WMAQ 11:30 Cee Davidson Orch.—WENR 2:00 "Varsity Out!" B:15 Farm News and Views—WMAQ WTMJ WLW 11:30 Neil Bondshu Orch.—WBBM WIBU 1240 WTMJ •20 0:18 Farm Sorvlcc—WBBM 8:00 WIND WCCO WKNR 2:15 Song Favorites. -

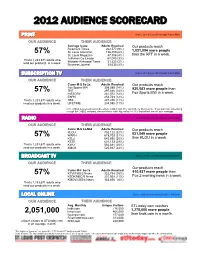

2012 Audience Scorecard

20122012 AUDIENCEAUDIENCE SCORECARDSCORECARD PRINT Source: 2011 St. Louis Scarborough Report (MSA) OUR AUDIENCE THEIR AUDIENCE Average Issue Adults Reached Our products reach Riverfront Times 202,577 (9%) 1,031,094 more people 57% St. Louis American 136,759 (6%) St. Louis Magazine 87,806 (4%) than the RFT in a week. Jefferson Co Leader 67,083 (3%) That’s 1,233,671 adults who Webster Kirkwood Times 51,225 (2%) read our products in a week. Business Journal 39,630 (2%) SUBSCRIPTION TV Source: 2011 St. Louis Scarborough Report (MSA) OUR AUDIENCE THEIR AUDIENCE Cume M-S 5a-2a Adults Reached Our products reach Fox Sports MW 308,088 (14%) 925,583 more people than 57% TNT 297,886 (14%) HISTORY 261,072 (12%) Fox Sports MW in a week. ESPN 254,749 (12%) That’s 1,233,671 adults who TBS 247,285 (11%) read our products in a week. LIFETIME 234,095 (11%) 51% of MSA households subscribe only to CABLE and 33% subscribe to SATELLITE. If you purchase advertising through the CABLE company, discount these reach figures by the 33% that will not receive your message. RADIO Source: 2011 St. Louis Scarborough Report (MSA) OUR AUDIENCE THEIR AUDIENCE Cume M-S 6a-Mid Adults Reached Our products reach KLOU 702,122 (32%) 531,549 more people 57% WARH 678,703 (31%) KSLZ 643,895 (30%) than KLOU in a week. KEZK 624,133 (29%) That’s 1,233,671 adults who KYKY 566,891 (26%) read our products in a week. KMOX 525,037 (24%) BROADCAST TV Source: 2011 St.