Bulletin 41 2000-2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

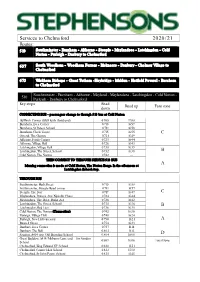

Services to Chelmsford 2020/21 Routes: 510 Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Steeple - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford

Services to Chelmsford 2020/21 Routes: 510 Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Steeple - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford 637 South Woodham - Woodham Ferrers - Bicknacre - Danbury - Chelmer Village to Chelmsford 673 Wickham Bishops - Great Totham -Heybridge - Maldon - Hatfield Peverel - Boreham to Chelmsford Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Mayland - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - 510 Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford Key stops Read Read up Fare zone down CONNECTING BUS - passengers change to through 510 bus at Cold Norton Bullfinch Corner (Old Heath Road end) 0708 1700 Burnham, Eves Corner 0710 1659 Burnham, St Peters School 0711 1658 Burnham, Clock Tower 0715 1655 C Ostend, The George 0721 1649 Althorne, Fords Corner 0725 1644 Althorne, Village Hall 0726 1643 Latchingdon, Village Hall 0730 1639 Latchingdon, The Street, School 0732 1638 B Cold Norton, The Norton 0742 -- THEN CONNECT TO THROUGH SERVICE 510 BUS A Morning connection is made at Cold Norton, The Norton Barge. In the afternoon at Latchingdon School stop. THROUGH BUS Southminster, High Street 0710 1658 Southminster, Steeple Road corner 0711 1657 Steeple, The Star 0719 1649 C Maylandsea, Princes Ave/Nipsells Chase 0724 1644 Maylandsea, The Drive, Drake Ave 0726 1642 Latchingdon, The Street, School 0735 1636 B Latchingdon, Red Lion 0736 1635 Cold Norton, The Norton (Connection) 0742 1630 Purleigh, Village Hall 0748 1624 Purleigh, New Hall vineyard 0750 1621 A Runsell Green 0754 1623 Danbury, Eves Corner 0757 1618 Danbury, The -

Historic Environment Characterisation Project

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT Chelmsford Borough Historic Environment Characterisation Project abc Front Cover: Aerial View of the historic settlement of Pleshey ii Contents FIGURES...................................................................................................................................................................... X ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................................XII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... XIII 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................................................ 2 2 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CHELMSFORD DISTRICT .................................................................................. 4 2.1 PALAEOLITHIC THROUGH TO THE MESOLITHIC PERIOD ............................................................................... 4 2.2 NEOLITHIC................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 BRONZE AGE ............................................................................................................................................... 5 -

The Old Vicarage Ulting, Maldon, Essex the Old Vicarage

The Old Vicarage Ulting, Maldon, Essex The Old Vicarage Ulting, Maldon, Essex A stunning former vicarage in a picturesque and convenient location 5/6 bedrooms � Boiler room 2 bathrooms (1 en suite) � Cellar 3 principal reception � Ground floor cloakroom rooms � Attached coach house Study � Swimming pool Kitchen/breakfast room � Mature grounds Conservatory � About 1.15 acres Utility room Chelmsford 9.4 miles (Liverpool Street from 36 minutes) A12 3 miles (junction 20) Hatfield Peverel 2.5 miles (London Liverpool Street from 43 minutes) Ulting is a pretty village between Hatfield Peverel and Woodham Walter. Hatfield Peverel provides a good range of village amenities including a supermarket, library and a number of notable pubs and restaurants. There is also a main line railway station with services into London Liverpool Street. To the west is the city of Chelmsford and its excellent choice of amenities including a bustling shopping centre, three superb private preparatory schools, two outstanding grammar schools, a well known independent school (New Hall), a station on the main line into London Liverpool Street and access onto the A12. The Old Vicarage is a very attractive, early 19th century country house which is listed Grade II. The house is of traditional construction of gault brick with tall and distinctive lattice windows to the principal elevations providing light and airy accommodation throughout. The house is spacious and well laid out with three principal reception rooms, a kitchen/breakfast room, a conservatory, a study and a utility room. A notable feature on the ground floor is the hall, which runs the length of the house and is mirrored above on the landing. -

Pevsner's Architectural Glossary

Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 1 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 2 Nikolaus and Lola Pevsner, Hampton Court, in the gardens by Wren's east front, probably c. Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 3 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Yale University Press New Haven and London Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 4 Temple Street, New Haven Bedford Square, London www.pevsner.co.uk www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk www.yalebooks.com for Published by Yale University Press Copyright © Yale University, Printed by T.J. International, Padstow Set in Monotype Plantin All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 5 CONTENTS GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 6 FOREWORD The first volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series appeared in .The intention was to make available, county by county, a comprehensive guide to the notable architecture of every period from prehistory to the present day. Building types, details and other features that would not necessarily be familiar to the general reader were explained in a compact glossary, which in the first editions extended to some terms. -

A Short History of Colchester Castle

Colchester Borough Council Colchester and Ipswich Museum Service A SHORT HISTORY OF COLCHESTER CASTLE 1066, the defeat of the English by the invading army of Duke William of Normandy. After his victory at the Battle of Hastings, William strengthened his hold on the defeated English by ordering castles to be built throughout the country. Colchester was chosen for its port and its important military position controlling the southern access to East Anglia. In 1076 work began on Colchester Castle, the first royal stone castle to be built by William in England. The castle was built around the ruins of the colossal Temple of Claudius using the Roman temple vaults as its base, parts of which can be seen to this day. As a result the castle is the largest ever built by the Normans. It was constructed mainly of building material from Colchester's Roman ruins with some imported stone. Most of the red brick in the castle was taken from Roman buildings. England, William's newly won possession, was soon under threat from another invader, King Cnut of Denmark. The castle had only been built to first floor level when it had to be hastily strengthened with battlements. The invasion never came and work resumed on the castle which was finally completed to three or four storeys in 1125. The castle came under attack in 1216 when it was besieged for three months and eventually captured by King John after he broke his agreement with the rebellious nobles (Magna Carta). By 1350, however, its military importance had declined and the building was mainly used as a prison. -

Radiocarbon Dates 1981-1988

RADIOCARBON DATES RADIOCARBON DATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1285 radiocarbon determinations carried out between RADIOCARBON DATES 1981 and 1988 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy of the dated samples from samples funded by English Heritage and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. between 1981 and 1988 The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are published, although, when many of these measurements were produced, high-precision calibration was not possible. At this time, there was also only a limited range of statistical techniques available for the analysis of radiocarbon dates. Methodological developments since these measurements were made may allow revised archaeological interpretations to be constructed on the basis of these dates, and so the purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Robert Hedges, Robert Otlet, Roy Switsur, and Jill Walker andJill Switsur, Roy Robert Robert Otlet, Hedges, Alex Bayliss, Front cover: Excavations at Avebury Henge, 1908 (© English Heritage. -

Electoral Changes) Order 2004

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 2813 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Essex (Electoral Changes) Order 2004 Made - - - - 28th October 2004 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) recommendations dated April 2004 on its review of the county of Essex: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Essex (Electoral Changes) Order 2004. (2) This Order shall come into force – (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005. Interpretation 2. In this Order – (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41). The Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (S.I. -

21 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

21 bus time schedule & line map 21 SOUTHEND - Creek Road ) View In Website Mode The 21 bus line (SOUTHEND - Creek Road )) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Canvey: 5:08 AM - 6:10 PM (2) Hadleigh: 5:40 PM - 6:30 PM (3) Hadleigh: 6:50 PM (4) South Ben≈eet: 6:37 PM (5) Southend-On-Sea: 5:43 AM - 6:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 21 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 21 bus arriving. Direction: Canvey 21 bus Time Schedule 87 stops Canvey Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:08 AM - 5:37 PM Monday 5:08 AM - 6:10 PM Travel Centre, Southend-On-Sea Tuesday 5:08 AM - 6:10 PM Whitegate Road, Southend-On-Sea 45 Chichester Road, Southend-on-Sea Wednesday 5:08 AM - 6:10 PM Chichester Road, Southend-On-Sea Thursday 5:08 AM - 6:10 PM Friday 5:08 AM - 6:10 PM Victoria Station Interchange, Southend-On-Sea Queensway, Southend-on-Sea Saturday 5:56 AM - 5:55 PM Civic Centre, Southend-On-Sea Blue Boar, Prittlewell 21 bus Info Priory Park, Prittlewell Direction: Canvey Stops: 87 Gainsborough Drive, Prittlewell Trip Duration: 85 min Line Summary: Travel Centre, Southend-On-Sea, Highƒeld Gardens, Prittlewell Whitegate Road, Southend-On-Sea, Chichester Road, Southend-On-Sea, Victoria Station Interchange, Southend Hospital South, Prittlewell Southend-On-Sea, Civic Centre, Southend-On-Sea, Blue Boar, Prittlewell, Priory Park, Prittlewell, Gainsborough Drive, Prittlewell, Highƒeld Gardens, Prittlewell School, Prittlewell Prittlewell, Southend Hospital South, Prittlewell, Prittlewell School, Prittlewell, -

Braintree District Protected Lanes Assessments July 2013

BRAINTREE DISTRICT PROTECTED LANES ASSESSMENTS July 2013 1 Braintree District Protected Lanes Assessment July 2013 2 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 5 2 Background ............................................................................................... 5 2.1 Historic Lanes in Essex ..................................................................... 5 2.2 Protected Lanes Policy in Essex ....................................................... 6 2.3 Protected Lanes Policy in Braintree District Council .......................... 7 3 Reason for the project .............................................................................. 7 4 Protected Lanes Assessment Procedure Criteria and Scoring System .... 9 4.1 Units of Assessment .......................................................................... 9 4.2 Field Assessment ............................................................................ 10 4.2.1 Photographic Record ................................................................ 10 4.2.2 Data Fields: .............................................................................. 10 4.2.3 Diversity .................................................................................... 11 4.2.4 Historic Integrity ........................................................................ 15 4.2.5 Archaeological Potential ........................................................... 17 4.2.6 Aesthetic Value........................................................................ -

Lst-Sov to 010119

Tuesday 01 January 2019 London Liverpool Street to Shenfield, Southminster greater anglia and Southend Victoria BUS TUBE BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS & T &&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&& Liverpool Street T Dep . 06.05 . Stratford T . 06.14 . Newbury Park T Arr . 06.29 . Newbury Park T Dep . 06.34 07.00 . 07.30 08.00 . 08.30 09.00 . 09.30 10.00 . 10.30 11.00 . 11.30 12.00 . Shenfield . 07.05 07.31 . 08.01 08.31 . 09.01 09.31 . 10.01 10.31 . 11.01 11.31 . 12.01 12.31 . Billericay Arr . 07.17 07.46 . 08.16 08.46 . 09.16 09.46 . 10.16 10.46 . 11.16 11.46 . 12.16 12.46 . Billericay Dep . 07.18 07.47 . 08.17 08.47 . 09.17 09.47 . 10.17 10.47 . 11.17 11.47 . 12.17 12.47 . Wickford 07.16 . 07.36 08.06 08.16 08.36 09.06 09.16 09.36 10.06 10.16 10.36 11.06 11.16 11.36 12.06 12.16 12.36 13.06 13.16 Battlesbridge . South Woodham Ferrers 07.32 . 08.32 . 09.32 . 10.32 . 11.32 . 12.32 . 13.32 North Fambridge 07.45 . 08.45 . 09.45 . 10.45 . 11.45 . 12.45 . 13.45 Althorne 07.55 . 08.55 . 09.55 . 10.55 . 11.55 . 12.55 . 13.55 Burnham-on-Crouch 08.06 . 09.06 . 10.06 . 11.06 . 12.06 . 13.06 . -

The Mid and South Essex University Hospitals Group (MSE) Is Comprised of Three Hospitals—Mid Essex, Southend and Basildon

SUCCESS IN ACTION CHALLENGE THE MID AND SOUTH CHALLENGE ACTION • Each year, NHS Trusts spend • A common challenge among NHS find beds. Nurses were also sometimes these factors impacted getting the right between £2 million and £7 million Trusts is a lack of visibility related to tasked with bed preparation, which patient into the right bed. RESULT adding capacity in an effort to treat real-time bed capacity—leading to would cause delays in bed turnaround, ESSEX UNIVERSITY more patients. Some have attempted beds not being cleaned as soon as they in addition to patients being placed in • Manual approaches to key processes SETTING THE building new wards and adding more became available, and the inability to the wrong wards because ED beds are were impacting the co-coordination of BAR FOR beds, but the challenges remain the fill beds when they were clean and ready. typically allocated on ‘time waited’ rather admissions and discharges from the HOSPITALS GROUP (MSE) same because core operational issues Periodically, nurses would roam wards to than ‘care needed.’ Combined, hospitals. SUCCESS haven’t been addressed. IN ACTION Billericay, United Kingdom ACTION • The merger of the hospitals was viewed caregivers to view and anticipate bed reducing patient wait times, decreasing app allows caregivers to view bed status in as an opportunity to review workflows and demand and availability in real-time. MSE discharge times and lowering a patient’s real-time from their devices to make operationalize the care continuum in order also analyzes operations by using length of stay. data-driven decisions, ensuring that to improve overall efficiency, maximize ca- predictive models to anticipate down- patients get to the right bed sooner and pacity and provide excellent patient care. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump)